Goodman Gallery presents ‘What Have They Done with All the Air?’ an exhibition of new drawings and sculptures by William Kentridge. Works featured relate to a new theatre production in the making, titled The Great Yes, the Great No, in which the artist uses the journey of a ship from Marseille to Martinique as a prompt for unpacking power, colonialism and migration.

William Kentridge’s dynamic, gestural and multi-disciplinary artistic practice continues to offer a persuasive argument for the pathway of an artist as requiring multiple mediums, in the honest pursuit of world-building and narrative cohesion. For Kentridge, an idea is never simple arrived upon through one singular medium – not his seminal theatrical works, nor his drawings, sculptures and more; rather, a body of work is the outcome of the layered tactility within his process; a process in which the ‘the prototyping’ of ideas are no less ingenious than their final culmination, say – this solo exhibition at Goodman Gallery being as textured as its reference point, Kentridge’s acclaimed theatre production ‘The Great Yes, the Great No.’

Stroke sculpture by William Kentridge, photographed by Chris Littlewood

Paper Procession Series photographed by Anthea Pokroy

This ‘act of prototyping with raw materials’ is the window into this exhibition, in which one is invited to peer into the tesseractic nature of Kentridge’s thinking – and ultimate arrival in creating or developing a body of work.

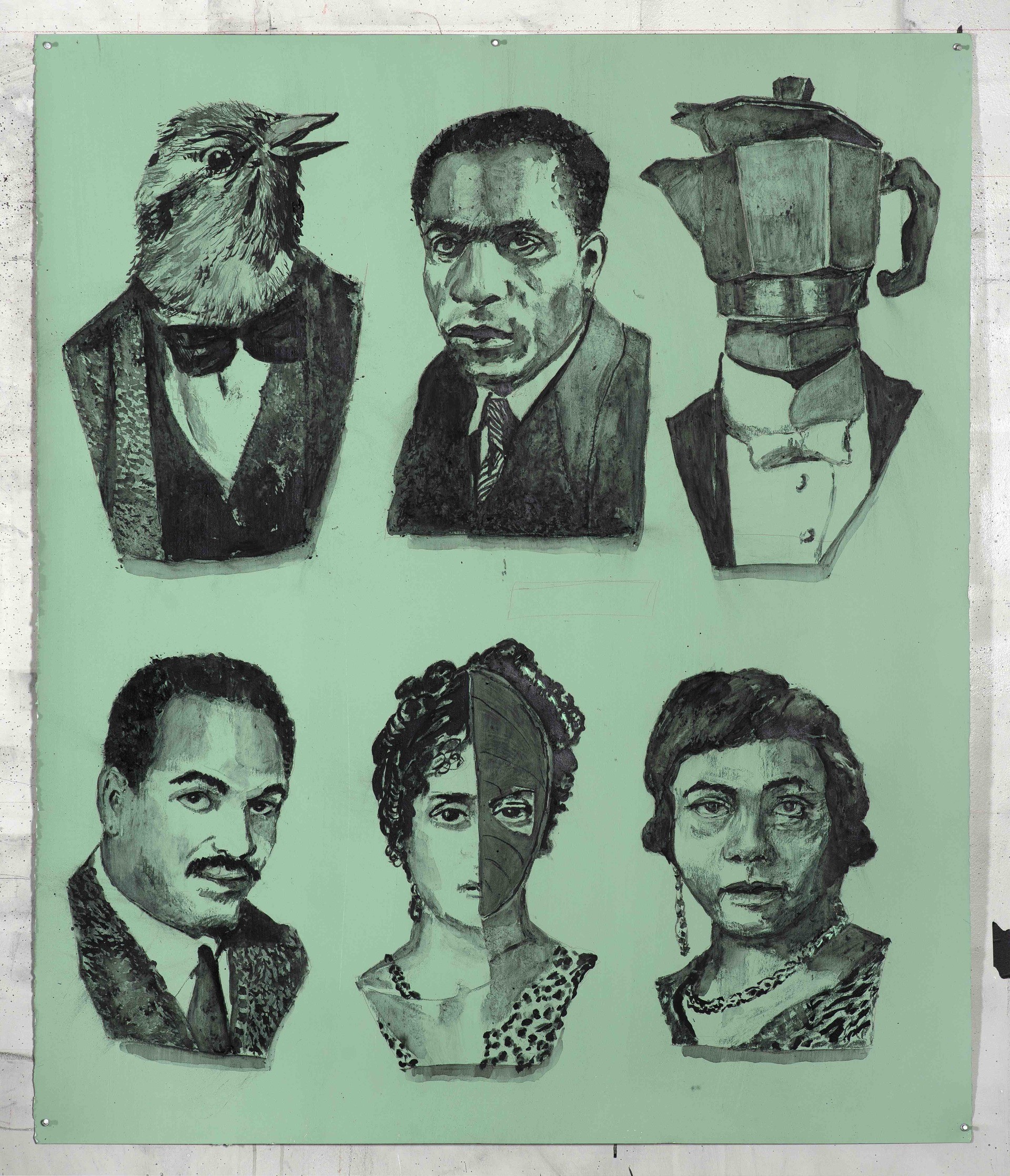

As the press release ( courtesy of Goodman Gallery) explains of the central ‘world’ to this solo show, namely Kentridge’s latest theatrical production – “the story behind The Great Yes, the Great No begins in June 1941, when a converted cargo ship, the Capitaine Paul Lemerle, sailed from Marseille to Martinique. Among the passengers escaping Vichy France were the surrealist André Breton, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam, the communist novelist Victor Serge, and the author Anna Seghers. The captain of the boat is Charon, the ferryman of the dead, who calls other characters onto the deck – Aimé Césaire, The Nardal sisters, who together with the Césaires and Senghor had founded the anti- colonial Négritude movement in Paris, in the 1920s and 1930s. Frantz Fanon joins the group along with Trotsky, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. The boat journey is the 1941 crossing of the Atlantic, but also references earlier crossings from Africa to the Caribbean, as well as contemporary forced sea crossings.” In this historical rendering, titanic intellectual and artistic figures are allegorical to a past re-imagined.

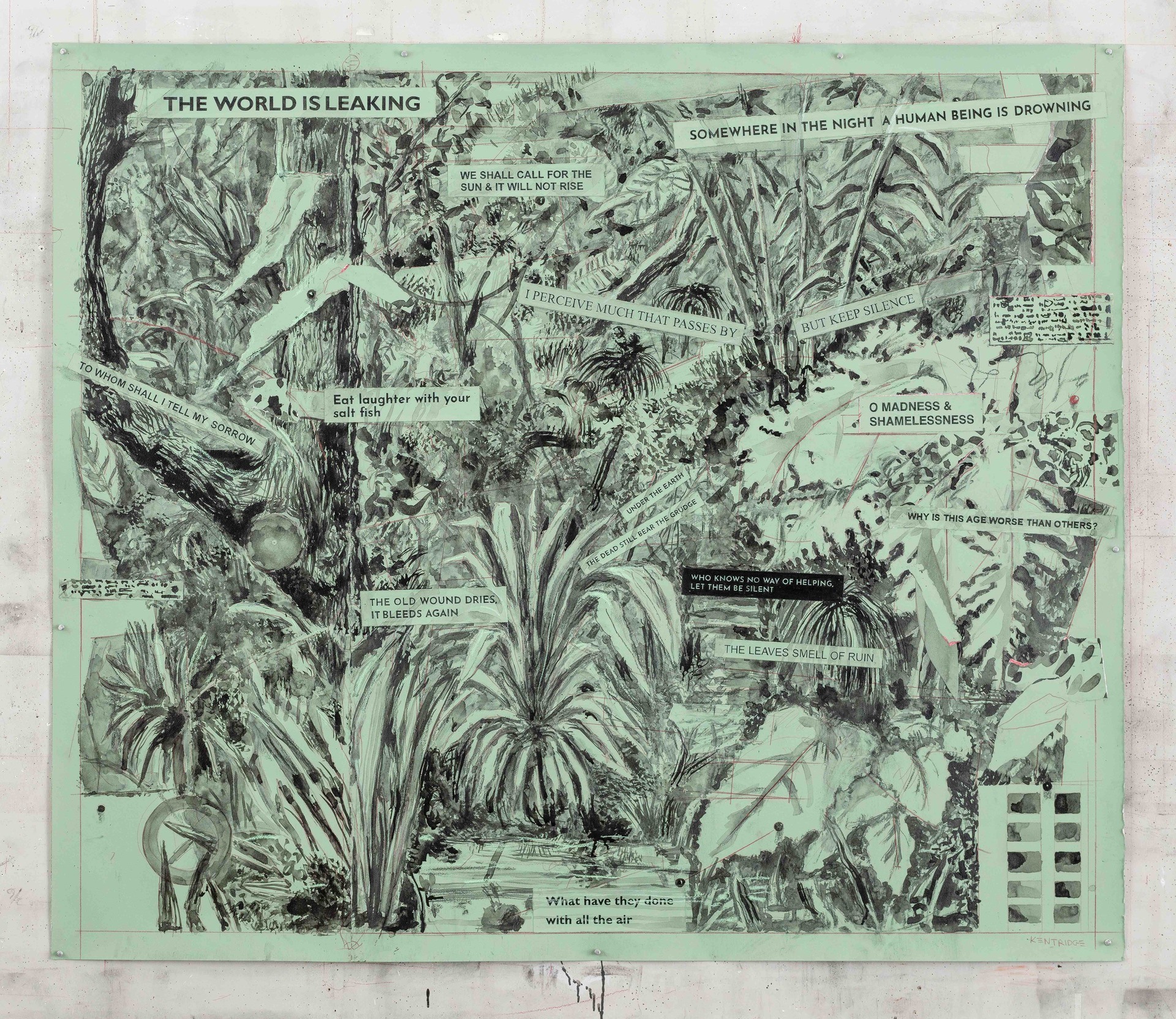

This exhibition, then, is a multi-disciplinary extrapolation of the production itself; featuring new drawings that are used as backdrops in the play, including portraits of characters in the play and imagined scenery from the ships arrival in Martinique – which are in fact, “an idea of the exotic Caribbean, which is in fact the domestic garden of Kentridge’s Johannesburg studio.” Thinking of this imagined potential from Kentridge – the ability to reference what is close to him in immediacy, to a counterfactual theatrical story – is a stunning way to disrupt the function of space and time when using real figures from the past, for imagined stories of the mind.

I can’t help but see – among the pieces in this show – Kentridge’s own yearning for a past in which figures representing an opposition to oppression (Breton, Trotsky, Kahlo and the like) or their own yearning for a more thoughtful world, as a personal attempt to reconcile the world we live in today. Namely, the post-colonial, post-apartheid fractured divisions that continue to persist. Perhaps, Kentridge is describing a dialectic view; asking to understand what might have been had our past not been saturated in violence; while creating a body of work that simultaneously accepts it, too.

In Gaston Bachelard’s seminal work ‘The Poetics of Space’, the philosopher proclaimed the experience of the physical ‘house’ as a metaphoric and device for the human soul or experience, saying that “we comfort ourselves by reliving memories of protection. Something closed must retain our memories, while leaving them their original value as images. Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home and, by recalling these memories, we add to our store of dreams; we are never real historians, but always near poets, and our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost.” For Kentridge, etched in his drawings, were a variety of existential exasperations – a kind of mnemonic device for this reconciliation between inquiry and acceptance, of conceptualising the many variations of the ‘home’ – our world, our society and each of our lives as it relates to the past.

Pour sculpture by William Kentridge, photographed by Chris Littlewood

“The World is Leaking”

“In the days to come, I shall be there”

“Let’s light the fuse & blow up the parade”

“We want no prophets in the house”

“All living things set up a house”

Included among the show is introduced “a collection of vibrant, hand-painted sculptures crafted from aluminium and steel, originating from small paper sculptures derived from a 19th-century accounting journal at the Chiesa di San Francesco Saverio in Palermo. Although not directly linked to The Great Yes, The Great No, these sculptures form the Paper Procession, offering insight into the costume-making process. William Kentridge and his collaborators engage in intensive workshops, using paper to conceptualise costumes and colours. Initially, paper collages transform into proto-costumes, occasionally evolving into standalone figures, exemplified by the For Degas puppets featured in the exhibition. Kentridge’s distinctive sculptural practice involves starting with torn paper, exemplified in the glyph bronzes that emerge from torn black paper, emphasising the importance of recognizing images as they unfold, rather than predetermined knowledge. The exhibition includes the Bull, a new bronze sculpture created from offcuts of black paper.”

Ultimately, Kentridge is not a historian, but his process is as rigorous as a historical inventory. As an artist for whom historical material forms his mastery, history serves as a rooting that allows Kentridge’s projects to oscillate perfectly between the imagination and reality – I encourage you to view this show by one of South Africa’s own titanic, historical figures.

Six Heads Marseilles Martinique Frantz F. et al by William Kentridge

The World Is Leaking by William Kentridge

About:

William Kentridge (b.1955, South Africa) is internationally acclaimed for his drawings, films, theatre and opera productions. Kentridge’s work is held in the following major collections around the world: MoMA, New York; Tate Modern, London; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Haus der Kunst, Munich; Sharjah Art Foundation, Sharjah; National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto; Guggenheim, Abu Dhabi and Zeitz MoCAA, Cape Town. The artist’s largest UK survey to date was held at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 2022. In the same year, Kentridge opened another major survey exhibition, In Praise of Shadows, at The Broad, Los Angeles. In 2023 this exhibition travelled to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Kentridge’s work has been seen in museums across the globe since the 1990s, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Albertina Museum, Vienna: Musée du Louvre in Paris, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea; Reina Sofia museum, Madrid, Kunstmuseum in Basel; and Norval Foundation in Cape Town. The artist has also participated in biennale’s including Documenta in Kassel (2012, 2002,1997) and the Venice Biennale (2015, 2013, 2005, 1999, 1993).

Written by: Holly Beaton