The way that we engage emotionally and intellectually with film is a kind of interactive experiment with the human psyche – and from it, we can derive our own meanings on navigating the complexity of life, and the nuanced matrices that compose who we are, who we want to be and where we might want to go. It is an incredibly exciting time to be a South African creative – this publication aims to stand as a testimony to this – and in the cavernous depths of difficulty in our nation’s socio-economic and political climate, art continues to serve its role as our species-specific medicine. In it, we trust.

Hallie Haller is a film director and media artist whose career and life charts the necessity of art precisely as this indisputable requirement for negotiating life; creating beauty, telling stories, building worlds and, as with their work with Girls in Film, impressing upon the lives of others along the way. In our conversation, among many things, Hallie offers an incredibly beautiful perspective on the role of SciFi and the surreal as genres to uncover the fabric that forms South Africa’s artistic, co-cultural landscape. Through their work across varying storytelling formats, from the art form of the commercial and branded films, to personal short and long-form films, to interactive media art and design, I find myself instilled with renewed understanding of the silent vow between all artists in this moment in time, as we face a digitised, unknowable future: the commitment to create, no matter what.

Of their formative years, Hallie shares that “I was born in Durban and I was in grade one in 1994 – you know, you’re colouring in an image of Nelson Mandela’s face in grade one, and that really defines the timeline you’re on. My parents wanted me to have access to certain things, so I went to schools where people didn’t look like me at all. Navigating these spaces of privilege, and reading a lot growing up, I desperately wanted to see more of the world.” With this sense of internal displacement, Hallie moved to Taiwan for six years – and for anyone who has left their home country, you will know just how critical this can be for reconciling and renewing parts of ourselves we may otherwise have waited many more years to find. To find ourselves in the cracks in the roads of other cities, or in the faces of strangers – where your anonymity is a kind of sacred treasure. As Hallie says, “I think there’s something important in living somewhere where you exist beyond your demographic. In Taiwan I wasn’t any of the labels that I grew up with and I got to feel very fluid, to be detached from my nationality and I think that helped me come back and occupy more fluid identities in the stories that I tell and shape the way that I view myself. That was really important for me and a huge privilege that I got to do that,” and from this experience, “there’s something about occupying multiple identities that is very present in my work now.”

Hallie Haller photographed by Gcobisa Yako

Hallie Haller photographed by Gcobisa Yako

Hallie’s entry into filmmaking came as a consequence of their studies in screenwriting – and this medium emerged sort of unexpectedly, as they recall, “I studied screenwriting and drama directing. I’ve always written stories – it’s how I live – and after studying screenwriting, nobody cares that you’re a twenty-year-old screenwriter! So, I started trying to make some of my own films. Film directing is such a complicated thing and especially at the time that I graduated, I didn’t see anybody like me lecturing, or have anyone as a role model. I didn’t realise I could actually be a director for a very long time.”

This realisation began to shift when Hallie created a short dance film called Belovely, inspired by a woman they loved. Hallie shares that, “you can really feel it in the film, the crush I had.” It was established filmmaker and executive producer of Fam Films, Mpho Twala who saw Belovely and believing in Hallie’s potential, encouraged them to try their hand at commercials; “It took somebody to tell me I could do it, and give me that permission, to pursue it as a career path,” Hallie says, and that “I now find really addictive about directing is the amount of self-work that you have to do, to work with other people under that pressure, with those timelines and expectations – it’s so unbelievably character building.”

Sci-Fi and speculative fiction serve as the modern medium for myth-making in our age, with imaginative narratives and allegorical tales that can reflect and critique contemporary issues while envisioning possible futures – whether through a queer lens that builds worldscapes beyond the binaries of society and heteronormativity, or as a tool to observe the cultural context of in say, South Africa – Hallie’s interest in Sci-Fi and the surreal has emerged as seminal grounds on which to walk their artistic journey, “I really love Sci-Fi and I also come from a documentary background, and I think elements of the two come through in my work. I love the hyper visual mode of storytelling that worldbuilding requires. It’s such a cool time to make Sci-Fi because everyone is asking questions about the visual language that we have inherited. A lot of Sci-Fi, historically, has had these Cold War, machine gun, action movie elements – and it doesn’t really have to be that anymore.”

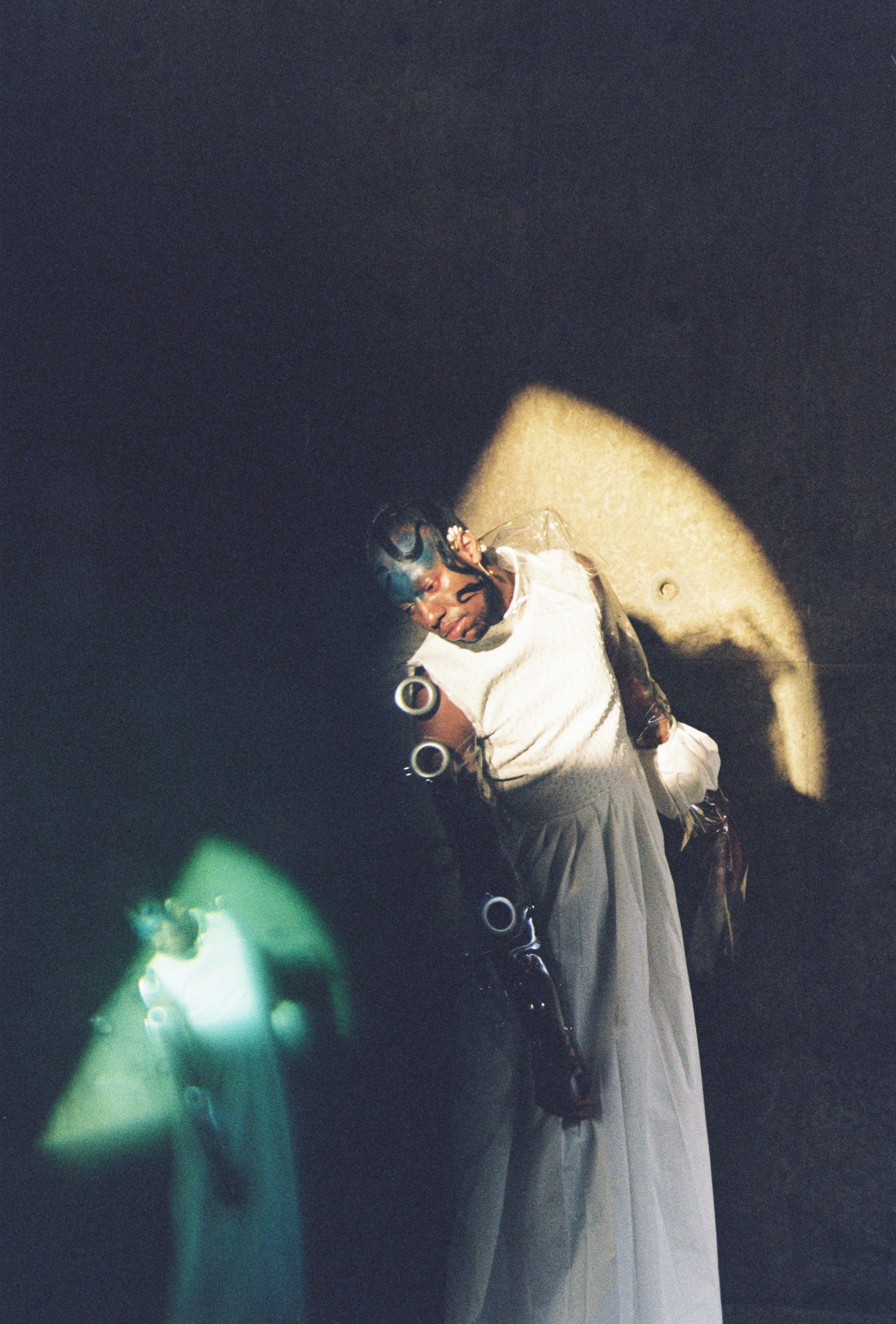

This distinct vision for Sci-Fi through a more tender, etheric and resolved lens is extended to Hallie’s photographic work; most notably, the images they shot of Moonga K for the release of GARDEN last year. Hallie shares that, “my photography is very much an artistic practice. It falls into the documentary and sci-fi space – like those images of Moonga K were about imagining him as this inter-planetary deity that exists beyond gender and time, and also archiving him as he released the new album – GARDEN – a work that he felt really embodied his voice and experience as an artist at that time. I’m learning to bring that lens to everything I do.”

Moonga K photographed by Hallie Haller

Moonga K photographed by Hallie Haller

“There’s something about revisiting Sci-Fi in a very South African space that I’m really drawn to. There’s so much to uncover in looking at the genre in a new way, when we can look at it through the lens of South African mythologies and histories,” Hallie explains, and that their fascination with the surreal is able to contain multitudes across genres, in which speculative explorations of the integration between the body, movement, and technology is a triadic focus in their creative approach, “I’m really excited by the surreal. The body, movement and technology are my focus and I think world building visuals allow me to play in that space. I can never get away from the body as technology, especially. I grew up dancing and if I move away from all American media tropes and move towards what is our Sci-Fi, it always brings me back to the body, movement and things that are rooted in nature. In one way or another, all the work I do is about intimacy and liberty. I want to imagine it better – for myself, at least, and hope that some of it resonates.”

Girls in Film was founded by Nikola Vasakova, a filmmaker and producer based in London, who launched the platform in 2017 with the vision to address the gender disparity in filmmaking, creating a space in which women, trans and non-binary filmmakers could connect, collaborate, and showcase their work. Since then, the organisation has grown to include chapters across the world – one of which is in South Africa, and for whom Hallie is a co-founder and director, alongside a team of filmmakers. Their fundamental aim is to equip people with the kind of roadmap that they wished they had when entering film, and Hallie explains that “I work with an incredible team. Vidal Thaver is the youngest person on our team and very important for that reason, she keeps us very connected to the purpose that we started the organisation for – to be the community we all needed when we were stepping into the industry. Gale Maimane and Jabu Newman are very established directors, and Chantel Clark occupies a completely different part of the industry in terms of being really respected as a screenwriter, and directs her own long-form work. Then there’s me, working between film and media art, so I think we have a really good balance.”

Collective action and community are what has kept lineages of women and queer folk safe throughout all history; and it’s within this legacy that Girls In Film finds its foundation as a support network, in which mentorship and guidance are integral for moving through one’s professional and personal life, within the context of film. Hallie explains that “there’s so many people asking questions like, ‘is it normal that somebody treats me this way in an internship?’ or ‘do you know who I can talk to about applying for a fellowship?’. A lot of the work we do is on a very one to one, human level. Representation is really important for many reasons, but to share in how to deal with similar problems, you need advice from someone like you who is dealing with those challenges, and that’s essentially what our organisation does.”

Girls In Film is a registered NGO, and they’re in the process of looking for funding to initiate their alumni program, which will “be focused on running emerging filmmakers through every step that they need to understand the ecosystem. GIF is hoping the alumni program will launch filmmakers by facilitating press opportunities, local and international screenings, panel appearances and, most importantly, getting introduced to the markets and other film communities that get films made. As Girls in Film, we can’t fund your film but we can help you to navigate the industry. And for young filmmakers who don’t inherit the social capital and networks to do that, my experience has been that the information and support is critical.”

‘Thati Zulu Road to Paris’, a film by Hallie Haller for adidas

Ecstatic Exit, a film by Hallie Haller, poster design by Isabel Pereira

The strategic focus of Hallie as director at GIF and film-maker in their own right, is the acceptance and understanding that finance – and economic barriers – are ever-relevant, and requiring continued development, to which they explain that “something we’ve noticed is that some people from previously disadvantaged backgrounds who become filmmakers find themselves in the commercial space, because of the economic opportunities, getting the funds to sustain themselves as an artist, but never really bridge into the long-form world because the industries are completely separate spaces to each other. We’re trying to build that bridge between the brand space, and those who want to pursue the longform space, because commercials are where a lot of young filmmakers are getting upskilled, and there can be an information gap in how to move beyond that.”

Hallie doesn’t abide by confinement to a singular form of expression; and in service to their own occupation of a multiplicity of identities, their initiation into media art is a continuing practice of discovery. Earlier this year, they showcased ‘Machine Swim’ – an interactive display of lights at the Spier Light Art Festival, with viewers using their own body movement to create illuminated figures in contact with an artwork where people dance with a machine, and see it respond through projection in real-time. I ask Hallie what brought them to this point of inquiry, from behind the lens and into the installation space; “The first job I ever had was at Design Indaba and that makes you a terrible employee because you just want to change the world through art, forever. cinema is its own interesting niche space,” but that, “sometimes you make something for two years and people watch it for ten minutes, and something I’ve been thinking about is how to expand that world so that I can get feedback, or co-create co-create with an audience rather than just speaking to them. That’s what has brought me into the media art world, it’s really about wanting interaction and for the audience to be part of the making process.”

Hallie muses that “everything has been in post (production) for ages!” with the rest of 2024 set to welcome a variety of releases. ‘Ecstatic Exit’ tells the story of survival and interconnectedness, through dimensions and using movement, with Hallie noting that, “I’m really excited for Ecstatic Exit. It’s taken us so long to get it through post, and it’s a very clear expression of how I would like to use Sci-Fi. It’s taken me a long time to find that language and this film is the first step in that direction, and I want it to be a series.” and that in addition “I’ll be releasing ‘It’s Lit’, a South African horror film – a dystopian look at what it’s like to be abandoned as a young person in our country, and we’re currently in production with ‘Jodie Is Infinite’, shot with Yellow Bone.”

Lastly, Hallie shares their advice for emerging filmmakers and artists; and it’s one that we hear often at CEC – that trial and error is truly the practice – as Hallie says, “just keep making work. It actually doesn’t matter if you like it or if it’s perfect. You just have to keep making work, you learn so much each time you do it, and waiting for permission or for the resources, can be a trap. Just make something, make anything. And find community. It’s such a waste of energy to think that you need to do things alone. The quicker you find community, the quicker these spaces open up.”

Written by: Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za