In the valley of distribution warehouses and embedded beneath stratas of logistics, lies a story about just how much the way in which we interact with fashion has changed, forever. Online shopping is about as normal to us now as the smartphones that we use – but if you asked someone in the 2000s what their cell phones might be able to do in just a few years, they might struggle to reconcile a future in which one’s phone is almost an extension of the body – full of endless apps for every kind of human thought, desire or need. Fashion, too, has changed profoundly, benefitting from the same kind of integrated advancements that have touched just about everything else in our lives. Yet, the idea of ‘click, pay, delivery’ in the realm of fashion is still kind of novel, if we think of the relative influence this form of shopping has had in just two decades. With it, the concept of purchasing a piece of clothing has led to stunning changes in marketing, advertising, brand-building, logistics, technology and more.

Fashion as an industry today is inseparable from the tech-start up culture originating out of Silicon Valley in the late 1990s, and its transformation is a tale of globalisation, influenced by the pursuit of accessibility and entrepreneurship. South Africa’s own local context similarly bears all the markers of this tale. This chapter of Interlude takes a look at how E-Commerce came to change the way we interact with fashion, and touches on the hyper-localised backdrop of South Africa’s growth in this regard.

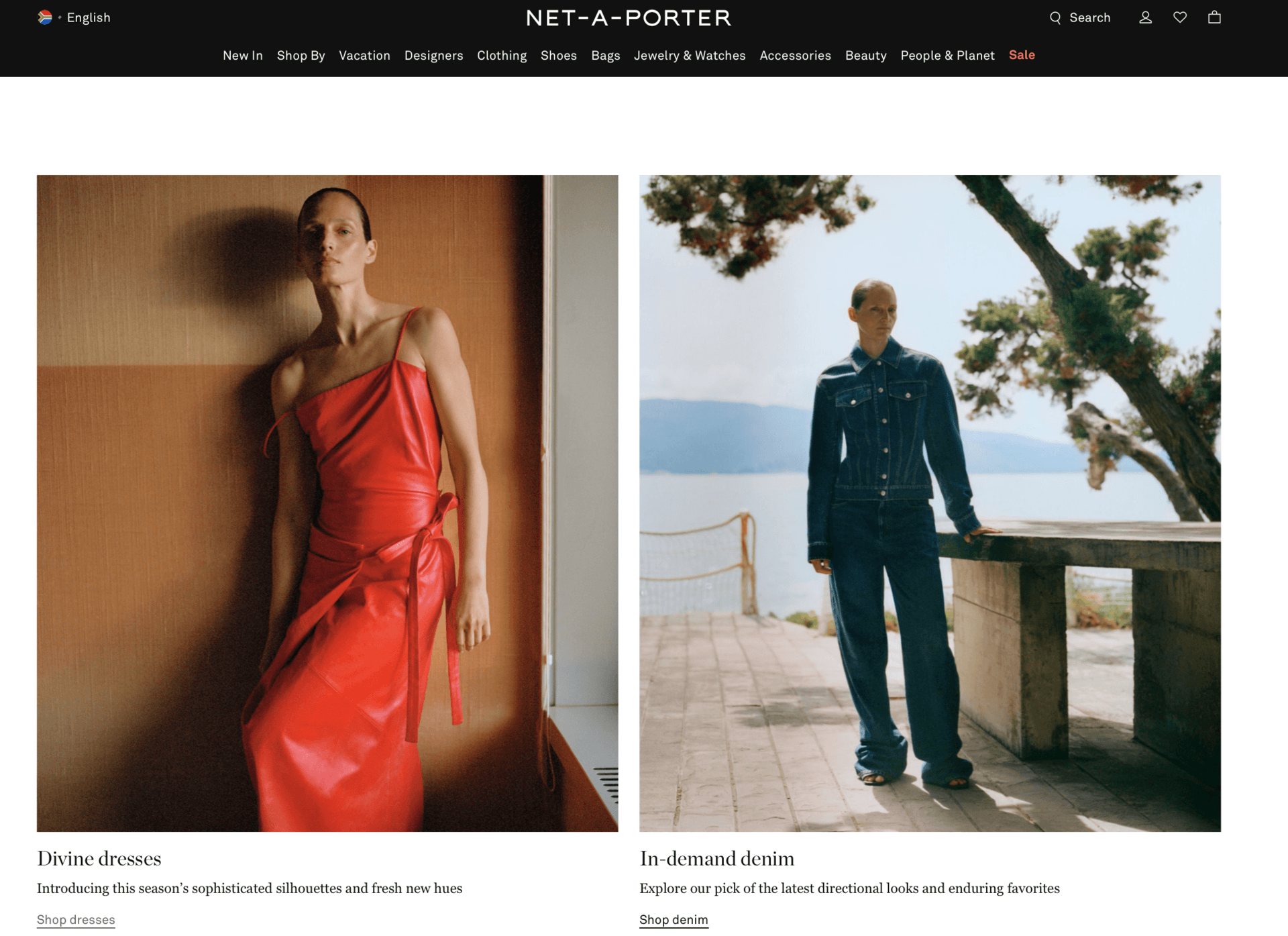

In 2000, Natalie Massenet changed fashion commerce forever with the launch of Net-A-Porter: an online fashion platform that introduced the concept of a truly “fashion-forward” e-commerce retail concept that integrated luxury fashion purchasability, professional styling, and editorial content. The internet in the year 2000 was in a very antiquated form of itself (compared to today) with dial-up-connection being its operating power, and website design was generally very basic (complex websites took up a huge amount of bandwidth to run). E-commerce was in its infancy and posed a huge cyber security risk – basically, it was the dark ages, and the idea of an online fashion ‘marketplace’ was actually revolutionary. When Net-A-Porter launched, it featured a magazine layout, and its marketing strategy used the technique of fashion editors and stylists to create the sense of a fashion catalogue; it was Vogue or Harper’s, only online, and you could click on the images of what you wanted and have it delivered to your door. This earliest iteration of the ‘digital magazine’ prototype fused with an actual commercial function was long before any brand or designer had their own website or Shopify – let alone an Instagram or any kind of presence on a rotation of social media platforms.

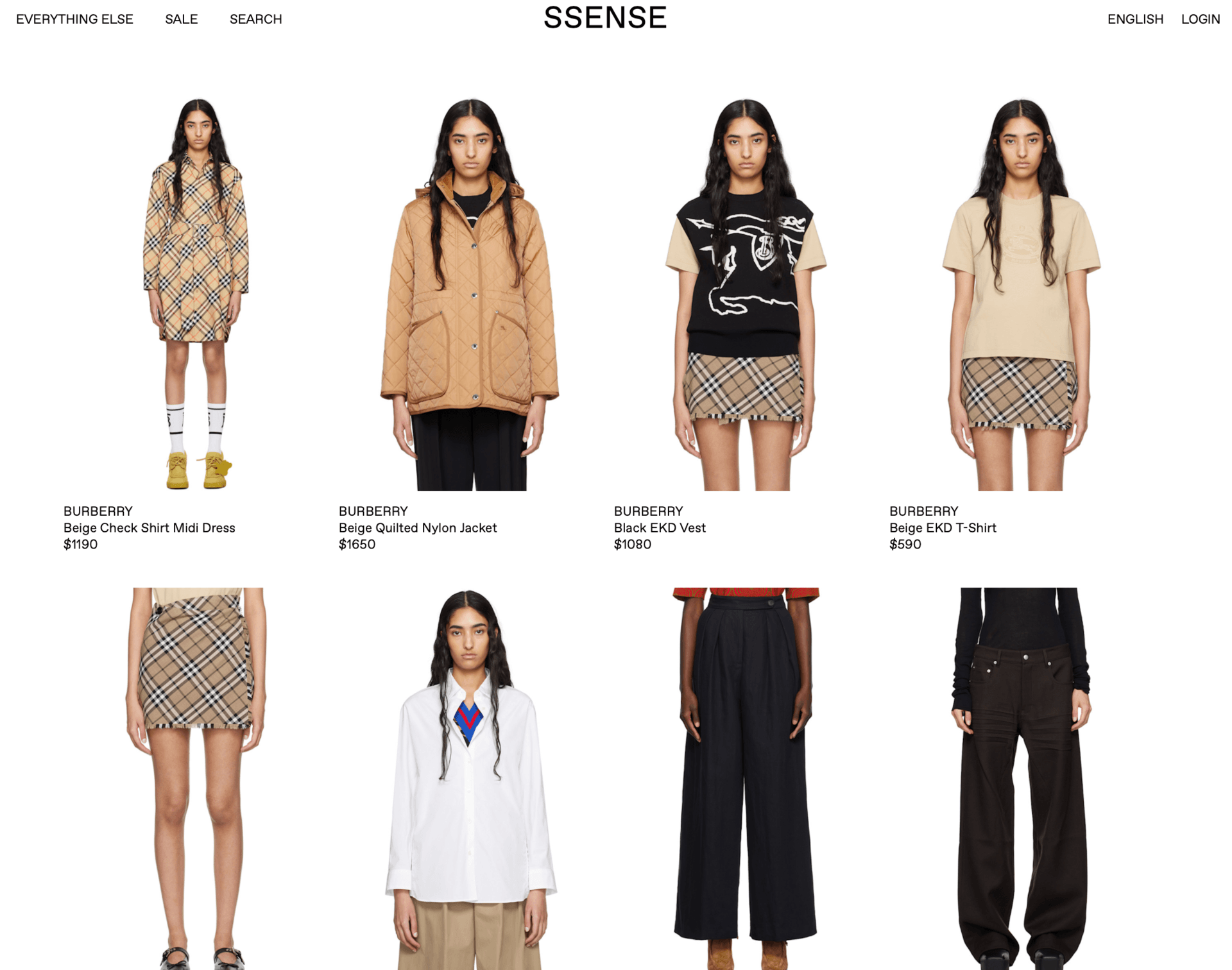

Screenshot of Ssense.com Womenswear Page

Screenshot of Net-A-Porter’s edits style strategy

That same year, ASOS was launched – meaning ‘As Seen On Screen’ – as the ‘high-street’ mid-weight answer to fashion e-commerce. The aim was to democratise fashion, introducing the notion of ‘fast-fashion’ to a digital and clickable format, and targeted for a younger audience. ASOS and Net-A-Porter’s early conception showcase the ultimate motivation behind e-commerce; the abundance of choice, anytime, anywhere and for any occasion. By 2001, ASOS was already listed on the London Stock Exchange – and its success, along with Net-A-Porter’s, laid the groundwork for the emergence of platforms like Zalando and FarFetch, and niche vintage spaces like Vestaire.

The idea that order fulfilment could take place anywhere in the world to satiate all kinds of sartorial needs revolutionised the fashion industry. This global reach was facilitated by the development of sophisticated e-commerce supply chains with integrated and efficient logistics networks and advanced inventory management systems. Warehouses were built en-masse and strategically located near key markets, and enabled faster delivery times, while partnerships with international shipping companies ensured that products could reach customers in even the most remote locations. Supported by technologies like RFID and real-time tracking systems improved inventory accuracy and allowed for seamless order processing. The result of this intricate supply chain is what we know today – and which almost all brands are engaged with on some level. E-commerce has dawned an unprecedented level of convenience and choice for shoppers, who can now access the latest trends and niche items from around the world with just a few clicks.

In 2010 in a tiny shared office space in Salt River, Cape Town – Luke Jedeiken, Claude Hanan, and Daniel Solomon were cooking up ‘CityMob’, a startup initially focused on developing digital discount vouchers. It would be their rebrand into Superbalist that marked the trio’s entrepreneurial magnum opus; one of South Africa’s first and most successful fashion retailers. Founded during the millennial golden years, the founders recognised the growing potential of e-commerce in the South African market and built a platform that combined local fashion sensibilities with global trends: a local focus with a global vision. Using a symphony of integrated tactics from the site’s blog ‘The Way of Us’, an in-house team of stylists, editors, buyers, copywriters, UX designers – to say Superbalist was cutting edge for its time is an understatement. A little bit of my own lore includes being a ‘client concierge’ as one of my first jobs for Superbalist; they had just been bought by Takealot, and their massive open plan office in Foreshore felt like being immersed in a real industry with movers and shakers of the future. After selling to Takealot, Jedeiken and Hanan are now at TFG’s Bash – to spearhead the company’s digital transformation, leveraging their extensive experience in e-commerce to enhance TFG’s online presence and streamline its omni-channel strategies.

If you’ve shopped on Superbalist, you’ll know that there is always a discount available and some kind of sale taking place – this ‘flash sale’ marketing technique is omnipresent, and was a foundational factor in the development of Superbalist. In a landscape like South Africa, where online shopping was novel and unknown in the early 2010s, the incentivisation born from psychological manoeuvring in constant sales led to a significant boost in consumer engagement and trust. By offering continuous discounts and flash sales, Superbalist effectively lowered the perceived risk for first-time online shoppers, making it more appealing to try out the new medium – a tried and true strategy that encouraged repeat purchase globally, ultimately aiding Superbalist in building a loyal customer base that became accustomed to checking the site regularly for deals. The constant stream of promotions created a sense of urgency, prompting customers to make quicker purchasing decisions and reducing the likelihood of ‘cart abandonment’. This approach drove immediate sales and established Superbalist as a go-to destination for trendy and affordable fashion; with the promise of fashion for any person, almost anywhere in the country.

“Consumption” by Ron Lach via Pexels

The success of fashion e-commerce is a feat of technological integration. With tech-driven business models, emergent strategies like ‘omni-channel’ touch points mean that your favourite retailer is a cohesive entity, available to you on a website, via an app, and has a unified identity on social media platforms. Tech has enabled companies to be present in your life no matter where you are; a huge departure from needing your arrival at their physical store in order to secure a sale. The pulse of online retailers are pumped by sophisticated data analytics that are constantly recording and negotiating every interaction with customers – old, new, potential or simply hard to win over.

The future of fashion retail is poised to be shaped by a continued evolution of technology and shifting consumer preferences. We will likely see a future of augmented reality (AR) fitting rooms, AI-driven personalisation, and blockchain for transparent supply chains. As digital aesthetes prioritise authenticity, platforms like Ssense that use deeply thoughtful, culturally relevant and almost satirical marketing strategies signal online fashion’s behemothic position as entities of cultural production; as we look to them to define the tastes and desires that we never actually knew that we had. Simultaneously, the growing importance of sustainability and ethical practices present massive challenges. As I’ve written many times before, fashion faces immense mounting pressure to adopt sustainability as a core concern; and brands will have to find ways to reduce waste, and ensure fair labour practices, pushing retailers to rethink their supply chains and business models.

If in twenty four years, people can go from ordering over a telephone with a code from a catalogue to receiving a garment to clicking a few buttons on a screen — surely, technology can reshape the next phase of online retail?

Written by: Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za