When I was 11 years old at a small girls’ school in Cape Town, we had a ‘lifestyle day’ for the grade 5, 6, and 7 students. For this event, various teachers offered mini classes on self-care and hygiene habits. In retrospect, I think it was a thoughtful way to impart valuable tools to us, especially for students who, perhaps due to their home circumstances, might not have been aware of such. I was chosen as the class volunteer to demonstrate a simple skincare routine: cleanse, tone, and moisturise, and it’s suffice to say — I’ve never looked back and maintaining some kind of routine has felt as critical for my existence as drinking water or eating food.

It’s interesting to look back on this moment, in the context of researching this piece and understanding just how instinctively young girls are socialised to prioritise skincare and beauty — even in the most noble, helpful pursuits by a group of well-meaning, female teachers. The expectation is embedded so deeply that it feels non-negotiable; we grow up understanding these routines as ‘self-care,’ essential acts tied to our sense of worth and identity.

Caring for oneself is framed as fundamental to our being, making these routines feel less like choices and more like intrinsic responsibilities. This idea connects self-care to our very core, subtly reinforcing that, with these actions, we’re both caring for our skin *and* validating our place in the world. The girlies know (even my husband knows, too, thanks to my encouragement of his own simple routine) just how invigorating and livening it feels to purchase, arrange and apply skincare products. But like everything in this deeply consumerist culture founded on excess, skincare and the pressures of the pursuit of perfect skin, largely implored by the internet and beauty influencers, can become a dangerous obsession. We’re witnessing this occur in leaps and bounds.

‘CUT AND PASTE’ photographed by Fanette Guilloud, via Death to Stock

‘Injectables’ photographed by Cottonbro, via Pexels

The beauty industry’s relentless marketing machine whose legions of influencers, all touting the perfect skin with each new product in an effort to gather us all in the pursuit of perfect skin, features, and body, has given rise to a troubling new term: dermorexia. Hesitantly coined by beauty journalist Jessica DeFino in her Substack newsletter The Review of Beauty, Jessica writes that, “ I previously used the term ‘dermorexia’ to describe a number of obsessive behaviours enabled and encouraged by the skincare industry today: teens devising multi-step anti-aging routines for fear of future wrinkles; adults going into debt to needle and laser their faces; a frantic, cross-generational preoccupation with retinoids and acids and glazing. I hesitated to suggest such an illness-coded word at first, but as Clein said in an interview for Mental Hellth, “it’s useful to have diagnostic categories so that people can get medical care.” And in the case of disordered skincare use, medical care is sometimes necessary; many of the above behaviours negatively affect skin health and mental health, especially for younger users.”

It’s important to note that ‘dermorexia’ is a cultural term at this stage and in using it as a term, sensitivity must be practised in terms of its association to very complex bio-psychosocial disorders such as anorexia.

The rise of such a term captures a growing obsession with skincare that is transforming once-healthy routines into compulsive, sometimes harmful rituals. While these routines may initially yield visible results, they often become insatiable, fueling an endless cycle of insecurity masked as self-care. This cycle can lead to damaged skin barriers, near-fatal allergic reactions, and psychological impacts that leave us feeling isolated and never fully content in our own skin – with every fix and trick meant to become the very thing that will reveal the most idealised, perfect version of ourselves. Our self-esteem is always under scrutiny and that’s not to mention the financial impact of buying things we can’t afford (racking up debt for costly procedures, too).

I can relate, given how often I’ve asked an aesthetician if I’m a candidate yet for treatments like PRP Vampire Facials or Sculptra—or the fact that I once went on an active-ingredient spending spree with niacinamide, glycolic acid, and salicylic acid that nearly destroyed my skin barrier. PRP (Platelet-Rich Plasma) Vampire Facials involve using your own blood’s plasma to promote collagen production and skin rejuvenation, promising smoother, more youthful-looking skin. Sculptra, on the other hand, is an injectable that stimulates collagen growth gradually, aiming to restore volume and reduce wrinkles over time. Both treatments, known for their natural-looking results, highlight our push toward increasingly complex—and costly—solutions in the pursuit of so-called ‘perfect’ skin.

Imagery courtesy of Pexels

‘Skin Deep’ photographed by Daniel Farò, via Death to Stock

There’s a fine line between diligent skincare and dependency, one that the beauty industry often blurs with clever marketing. By constantly introducing new products, driven by science, and encouraging multi-step routines the industry drives an insatiable need for ‘more’. There’s what you should be doing at home – 6 to 12 steps and no less – to the constant rotation of appointments at aestheticians, facialists and so on. Exclusive ‘must-haves,’ and intricate product layering fuel the promise of perfection, and somehow leave many of us constantly feeling as though our current routine is always incomplete. Rather than promoting balance, these practices reinforce a cycle of dependency, in which skincare can become less about care and more about keeping up with an ever-evolving standard.

As evidenced by the ‘Sephora Tween’ phenomena, the age at which this is occurring is becoming younger and younger; with Parija Kavilanz writing for CNN that, “tweens are obsessed with skincare. Their curiosity for all kinds of creams, gels, face masks and facial peels has even earned them a viral moniker: “Sephora Kids,’ and skincare experts are applauding the fact that kids as young as eight years old appear to be invested in taking care of their skin. The evidence is all over social media. At the same time, they’re concerned these young consumers are going about it in a risky way – from what they are buying to where they are buying it – and causing unnecessary damage such as rashes, allergic reactions and even skin burns.”

Can’t a girl just have a childhood, free of the onslaught of self-perception?

A few months ago, I sought out my darling friend and founder of skincare studio Edra, Liana Colvin, to help me with the weight of choice and lack of direction I felt with my skin. I had been told by a few specialists that I had what appeared to be mild rosacea – a chronic skin condition that primarily affects the face, characterised by redness, visible blood vessels – which I’d always put down to being a redhead with a natural ‘red’ undertone. Liana has been on her own journey to heal years-long, debilitating acne and found herself, too, overwhelmed and lacking actual help available. She has developed Edra as a resource and service that cuts through the noise and strips away the pretens around skincare and while not intended as medical advice, Liana’s help with a few adjustments to my products and routine, has been some of the most help I’ve had in years with my skin. “In my opinion, skincare solutions don’t begin with getting the most expensive or newest products,” Liana says, “in fact, I usually suggest people cut down on products. If your skin is inflamed or breaking out, adding too many products will likely aggravate it more. Sometimes, it’s just a few ingredients your skin doesn’t like, but often there’s a deeper issue. If your skin is a ‘problem,’ it’s giving you information about what’s happening in your body. It’s asking you to take a look at your mental, physical, and emotional wellbeing.”

In a culture of excess, even wellness is not immune, as the wellness industry has spawned its own medicalized term: ‘orthorexia’, which describes an obsession with health and wellness that can lead to disorder. I asked Liana about how she has approached finding healthy boundaries in her journey to transform her skin and her relationship with it, to which Liana says, “for me, the journey to healthier skin began with looking inward. I had an unhealthy relationship with myself, food, and exercise—I was so out of touch with what my body was asking for, jumping from one fad to the next, like kale and running (which I actually hate). I’ve learned to trust my gut; my body intuitively knows what it needs, and since I started listening, a lot has improved. You don’t need the trendiest products—just a few essentials, like an antioxidant, sunscreen, and retinoid. You don’t need the most expensive oil or cleanser, just ones with balanced pH that avoid harsh fillers and sulphates.”

Recent films like The Substance, featuring Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley, portray deeply problematic issues surrounding ageing and beauty standards in Hollywood—standards that, as we’ve seen with the ‘Kardashian era,’ quickly permeate the wider culture. The story follows Elisabeth Sparkle, who, on her 50th birthday, is abruptly dismissed from her long-running aerobics show due to her age. Following a car accident, she encounters a black market serum called ‘The Substance,’ which allows her to transfer her consciousness into a younger version of herself, leading to relentless and horrifying consequences.

As Bee Beardsworth discussed in her piece for Dazed titled ‘We Are Entering the Undetectable Era of Beauty,’ the recent comeback of Christina Aguilera, with seemingly 20 years shave off her physical age, demonstrates a shift that we are entering even more unchartered territory with beauty. As it turns out, many of these supposed procedures are skincare related — with Bee writing that, “Responsible for this move towards work becoming “undetectable”, Dr Trapathi explains, is a shift of focus towards skincare, with cutting-edge procedures like growth factors revolutionising the technology. “Growth factors used to be something we would get from our patient’s blood, but now we’re able to source them from things like bone marrow, umbilical cords, and are even bioengineering them in the lab. These treatments can dramatically improve the ageing process of the skin. It’s taking the aesthetic skin world to an entirely new level.” Dr Trapathi says that his assumption is that, rather than going under the knife, everyone in Hollywood is getting continuous skin treatments. “These skin boosters, skin treatments, growth factors, all of that stuff, they’re just readily available at their fingertips with little downtime.”

It will be harder and harder to find balance as we quantum-leap in advancements; and who’s to say this is even a bad thing? We are at the precipice of great change as a species, with some people even proposing that we will start to live much longer as a result of our scientific and technological revolution. The point is that we’re aware of the relationship of our actions and behaviours in relation to ourselves; does our skin care routine amplify our everyday experience and are we making safe choices? Do our skin appointments truly help us? Only we can determine that for each of ourselves — and if you ever get irritated with the ceaseless pull of the skincare industry, just know that you’re not alone. As Liana points out, “I truly believe this hyper-focus on our appearance creates a void designed to never be filled. Don’t try to fill it. Focus instead on connecting to your lifeforce—your body, your mind, and your connections with others. There are far more important things in life than what we look like. Healthy skin is necessary, and it can tell us a lot about our health, sometimes even indicating underlying chronic issues. But the industry has taken something valuable and turned it into a new unhealthy obsession.”

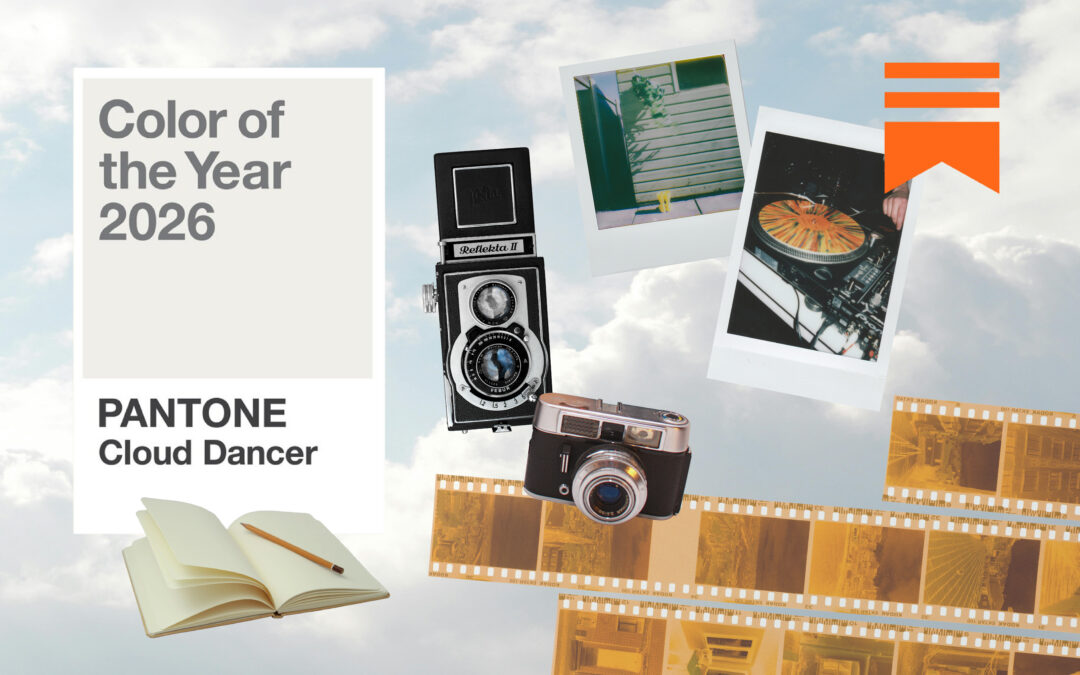

Featured image: “The Substance” Licenced by Alamy

Written by: Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za