Women’s fashion has been a persistent battleground, intertwined with our social and political expression in the world. It was only a hundred years ago that it became socially acceptable, in the western context, for women to wear pants; previously, this notion was completely scandalous. Today, we are more empowered than ever to break free from outdated dress codes and expectations, with the rise of our oscillating proclivities across gendered clothing being reclaimed a tool of self-expression. No longer confined by rigid rules dictating what is “appropriate” or “feminine,” we’re embracing styles that reflect our identities, values, and autonomy — and our sartorial preferences are more reflective of our everyday lives, whether across our career, interests or communities.

Fashion thinkers have been eyeing this movement as a salve in the midst of a political landscape that sometimes would have us believe that progression is obsolete. “For so long women’s fashion was about being flattering, centered on how slim or attractive could appear” says Munashe of the platform In The Fashion Focus, and that, “now women are dressing to prioritising individuality and comfort over conventional sexual appeal.”

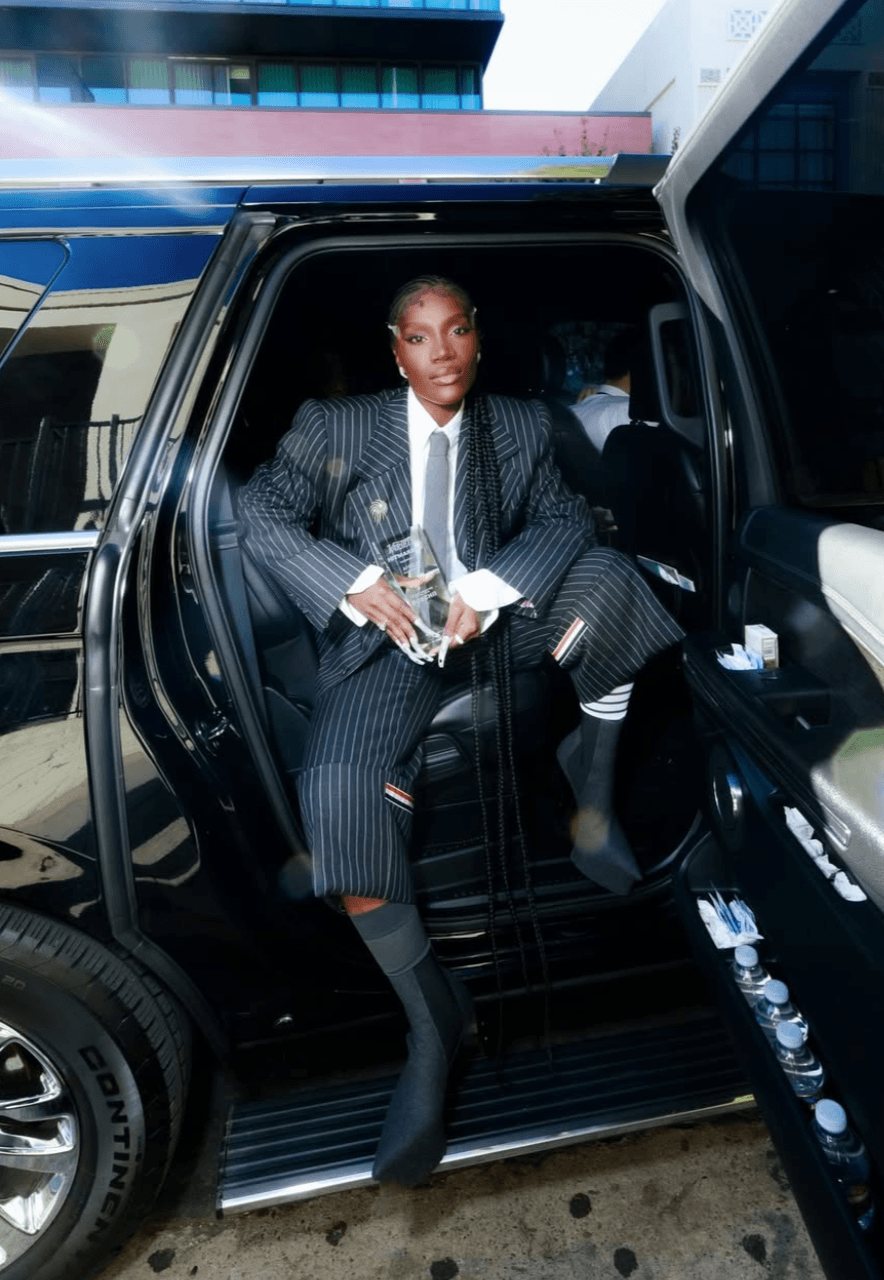

Across fashion, art, film and music— some of our most lauded style icons today are women who embody a fluidity in their dress sense. Think Doechii’s domination of the rap space, rooted in her vicarious resistance against any kind of sartorial norms: for the Grammy’s this year, Doechii worked with Thom Brown to develop a series of looks that paid homage to the legacy of suiting, and this is just one instance in which Doechii’s announcement of herself as a force to be reckoned with, is set against the backdrop of powerful, self-autonomous fashion choices. Iconic. Similarly, Billie Eilish has been that girl for a total immersion in boisterous, boyish fashion— despite any criticism she faced in the limelight from the age of 15, on how she was expected to perform or express herself as a ‘female popstar’, while niche style influencers like Marissa Lepps and Atiya Walcott are building incredibly successful careers from their incredible taste; and as Atiya’s tagline goes, “I’m Atiya Walcott, and I’m incredibly fashionable. Let’s get dressed together.”

Whether its Bella Hadid’s unwritten rules for her off-duty, street style looks; or the ‘shabby chic’ layered legacy of the Olsen twins — as Vogue, explains, ‘How To Dress Like The Olsen Twins This Winter’ — women’s fashion today signals the single greatest truth I believe in when it comes to fashion: firstly we dress for ourselves, and then we dress for the feminine gaze.

Doechii at the Variety Awards, via @doechii IG

Marissa Lepps via @marissalepps_ Instagram

I mean, few things are as validating as when another woman compliments your look, right?

Today, our most recent sartorial strides is certainly the influence of streetwear as a scope for dressing that exists beyond gendered notions and expectations. Streetwear titans like Supreme and Palace were once strictly for the boys, but like all good things in a world hopefully striving for progress; streetwear is now fully the domain of women, too. Hoodies, sneakers, and oversized silhouettes—once considered hyper-masculine and reserved for the skater boyfriends and brothers around us—are now entirely mainstream in womenswear. The idea of ‘flattering’ is a concept we must each reconcile with for ourselves; and this shift away from body-conscious dressing speaks to the deliberative abandonment of fashion in relation to the way women’s bodies have been historically controlled, commodified, and scrutinised. The only rules today are that there are no rules— and to dress for oneself might feel like a simple no-brainer today; but it is a hard-won expression of our place in the world as women.

Fashion as a form of expression finds itself most distilled when it speaks to self-ownership and breaking barriers on our own terms. As always, I think a short fashion history reminder will help contextualise just how recent it is that the idea of intermixing masculine and feminine notions of dressing: leading ultimately to where we are today, in which these ideals are becoming largely irrelevant.

For most of fashion history, the boundaries between ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ dress were rigidly enforced, with women’s clothing designed to emphasise submission and modesty. Even as late as the 1960s, women in many professions were barred from wearing pants to work, a restriction that only began to shift with second-wave feminism. The idea of blending masculine and feminine elements in everyday dress is a remarkably recent freedom.

Today, however, the integration of these aesthetics has progressed towards a more fluid self-expression. Women can wear deconstructed suits with delicate tulle, or a structured corset with oversized trousers, without making a political statement—simply because she wants to. This shift reaches beyond borrowing from menswear, toward dissolving the strict binaries that once governed fashion. The ability to mix and match these elements at will is a strikingly modern privilege—one that reflects how far we have come in reclaiming style as an extension of personal agency rather than conforming to any kind of societal expectations.

Yves Saint Laurent’s infamous Le Smoking tuxedo in 1966 marked a turning point in the history of womenswear. No longer a mere experiment, the suit was now positioned as aspirational womenswear—all at once sophisticated and undeniably sensual. Saint Laurent’s design was groundbreaking in both its aesthetic and in its implications; it gave women a way to command attention and assert authority in a world that still expected them to dress for the male gaze. As the late 1970s approached, the idea of women in suits gained momentum. Feminism’s second wave had encouraged women to reclaim autonomy over their bodies, their careers, and their wardrobes. Fashion followed suit, quite literally. Tailored blazers, high-waisted trousers, and sleek, structured silhouettes became symbols of independence, setting the stage for the power-dressing phenomenon that would define the next decade; the power suit era of the 1980s. As my mom will attest to, nothing was more as utterly self-empowering than donning shoulder pads that commanded presence.

The 1980s marked a radical departure from previous decades. As more women entered boardrooms, particularly in politics and executive roles, the suit became their armour of choice. This era of power dressing was defined by structured blazers, exaggerated shoulder pads, and sharp lapels—an aesthetic that borrowed heavily from traditional menswear but infused it with an assertive, almost aggressive femininity. The aim was clear: to be taken seriously in a male-dominated world, one had to look the part.

Possibly my favourite era of fashion, and where we begin to see womenswear actively depart from extracting its assertion through menswear, the 1990s ushered in a pared back revolution in women’s fashion. With the excess of the 1980s behind them, designers began to strip clothing down to its essentials. German designer Jil Sander’s evocation of a strict minimalism, championed by precision tailoring and an almost austere aesthetic, was her attempt at redefining femininity through simplicity rather than embellishment. For Jil, women were not dolls destined to be overly adorned and paraded around for a performance of fashion, and she’s quoted as saying that “I felt that it was much more attractive to cut clothes with respect for the living, three-dimensional body rather than to cover the body with decorative ideas.”

Meanwhile, Miuccia Prada introduced an intellectual, anti-glamour approach to fashion, embracing ‘ugly chic’ as a founding principle for Prada’s cult-like ascension in fashion during the 1990s. Paving the way for androgyny as a central theme in womenswear, and rejecting the traditionally ‘beautiful’ and overtly seductive, Prada instead found allure in the offbeat, the subversive, and the intellectual; creating a new kind of luxury that was less about status and more about nuance. This ethos was crystallised in her Autumn/Winter 1996 collection, famously dubbed Banal Eccentricity, which challenged the very notion of what was considered desirable at the time.

Martin Margiela, Fall 1997, photographer unknown, via VogueRunway.com Archive

Celine by Phoebe Philo, Pre-Fall 2012, photographer unknown, VogueRunway.com Archive

The show was a masterclass in defying conventional taste—filled with murky colours that hadn’t been cool since the 1970s, awkward silhouettes, and intentionally mismatched textures; by embracing the ‘ugly’—that which had previously been dismissed as dowdy or unstylish— Miuccia was announcing a guiding position for a new generation of women. She proved that femininity did not have to be soft or overtly sexual; it could be cerebral, ambiguous and even unsettling, and in the midst of all this, one could still be impossibly chic and sensual. Prada is part of the sartorial legacy we have today in rejecting the idea that femininity must be linear or easily digestible, instead offering clothes that challenge what it means to be a woman in any given moment.

This decade also saw the rise of grunge and deconstructed fashion. Designers like Ann Demeulemeester and Martin Margiela rejected the polished professionalism of the previous decade in favor of raw, unfinished aesthetics. By the 2010s, Phoebe Philo’s Céline had redefined luxury womenswear once more, making relaxed, effortless tailoring synonymous with empowerment.

The rejection of hyper-sexualized silhouettes and restrictive garments does not equate to a rejection of beauty, sensuality, or femininity itself, but rather a redefinition of these concepts on women’s own terms. The designers leading this charge—figures like Simone Rocha and Molly Goddard—are reclaiming femininity, and untangling it from the expectation of passivity or submission. Their voluminous silhouettes, exaggerated ruffles, and whimsical layering speak to a form of femininity that is bold and unapologetic, a visual language of defiance that does not need to conform to conventional ideals of desirability. The intermixing of feminine and masculine, as Nina Miyashita wrote for Refinery29 means that “if you follow more traditional rules of fashion, you might look at these kinds of outfits and think, ‘But they don’t really go together.’ And the truth is that no, they didn’t before, but we’ve chosen to reimagine gender, sex appeal and femininity through our wardrobes by choosing to showcase all our preferences at once. And it may look eclectic and mismatched, but that’s kind of the whole point.”

Womenswear today is centred on expanding the vocabulary of fashion to allow for multiplicity. We are not bound by binary choices of power versus softness, masculine versus feminine. Instead, we can actually wield fashion as an extension of our autonomy, shifting between aesthetics as we see fit. This fluidity signals our deeper cultural progression—one in which our personal expression is finally taking precedence over societal prescription.

Fashion is our self-authorship, and as Courtney Love so iconically blurted out at the MTV Video Awards in 1998 in response to her recent appearance at the Oscars ( as a female rockstar in a male dominated space), “we as females have thousands and thousands of years of fashion in our DNA. We want to wear nice fucking clothes, it’s part of what we do! If you have an opportunity to go to the Oscars in a fabulous gown and be absolutely fabulous, you’re going to fucking take it. I don’t have to, like, to listen to rules. Who made that rule? Some dumb guy.”

Written by Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za