For a long time, Jakinda Boya lived inside sound. As one half of Stiff Pap — one of the most singular and uncompromising electronic projects to come out of South Africa in the past decade — his creative life was built from collaboration, performance, touring, and the charged energy of rooms full of people. The project took him far and wide, and into a world in which music, image, and attitude were inseparable. Still, the demands of musicianship are always bound to the cost of performance. “With my personality, I know I might seem talkative, but I’m actually very quiet and very shy,” Jakinda says. “I really love painting because it’s just me.”

There is something decisive about Jakinda and his Stiff Pap co-creator Ayema Problem stepping away from the work at a high point. While the duo released a track last year, and will endeavour to do as and when the right moment naturally arises, both are now focused on their own projects.

Now, Jakinda’s primary focus is his work under the name Lil Loewe — iconic to say the least, and a moniker that nods to an ongoing fascination with fashion and style as aesthetic language. The work for him now moves in another direction; away from scenes and stages, toward solitude and the testing discipline of oil painting. As I remark to him in our conversation, there is something compelling about applying such a storied, traditional medium to the lens of figuration and menswear in contemporary Johannesburg, and in the midst of the city’s creative awakening. It is an artistic archiving of this present cultural zeitgeist; and Jakinda has committed himself to a practice built on repetition, attention, and a private labour of learning how to see. What has emerged, as he explains, are self-inquired psychological figures; attempts to paint what it feels like to be here, now.

Jakinda’s route into image-making was never straightforward, and it was shaped early by both constraint and improvisation. He studied film at UCT, drawn to a medium that promised narrative and atmosphere, but quickly discovered how deeply access and money shape what is possible. “Filmmaking is so collaborative, but it’s also really expensive to make a good film,” he says. In their final year, students were required to produce a short film as their exam, which meant fundraising their own budgets. “Everybody had to ask their families and try to get money together. I don’t come from money, so I was like, who am I going to get the money from? Some people managed to raise like R100,000 for a student film. Then when it was time to show the films, you could really see the difference in what people were able to make.” UCT’s equipment library meant that everyone could, at least in theory, still produce something — “even if you don’t have money, you can still make something” — but the gap remained visible. It is an early encounter with a pattern that repeats across South African creative life; talent and drive working within the constraints of uneven material conditions, and the understanding that the medium you choose can be as much an economic decision as it is an aesthetic one.

Jakinda Boya photographed by Assante Chiweshe

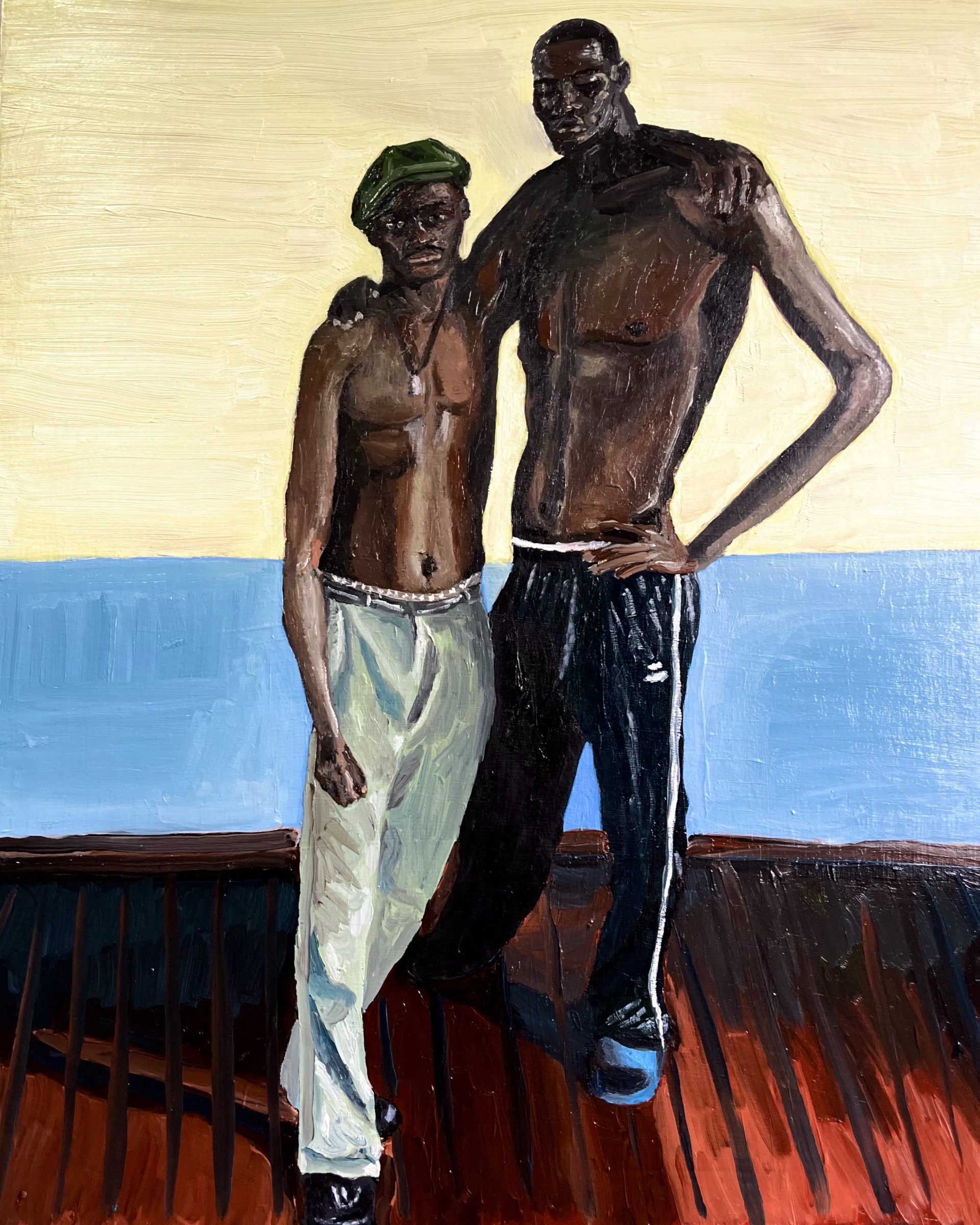

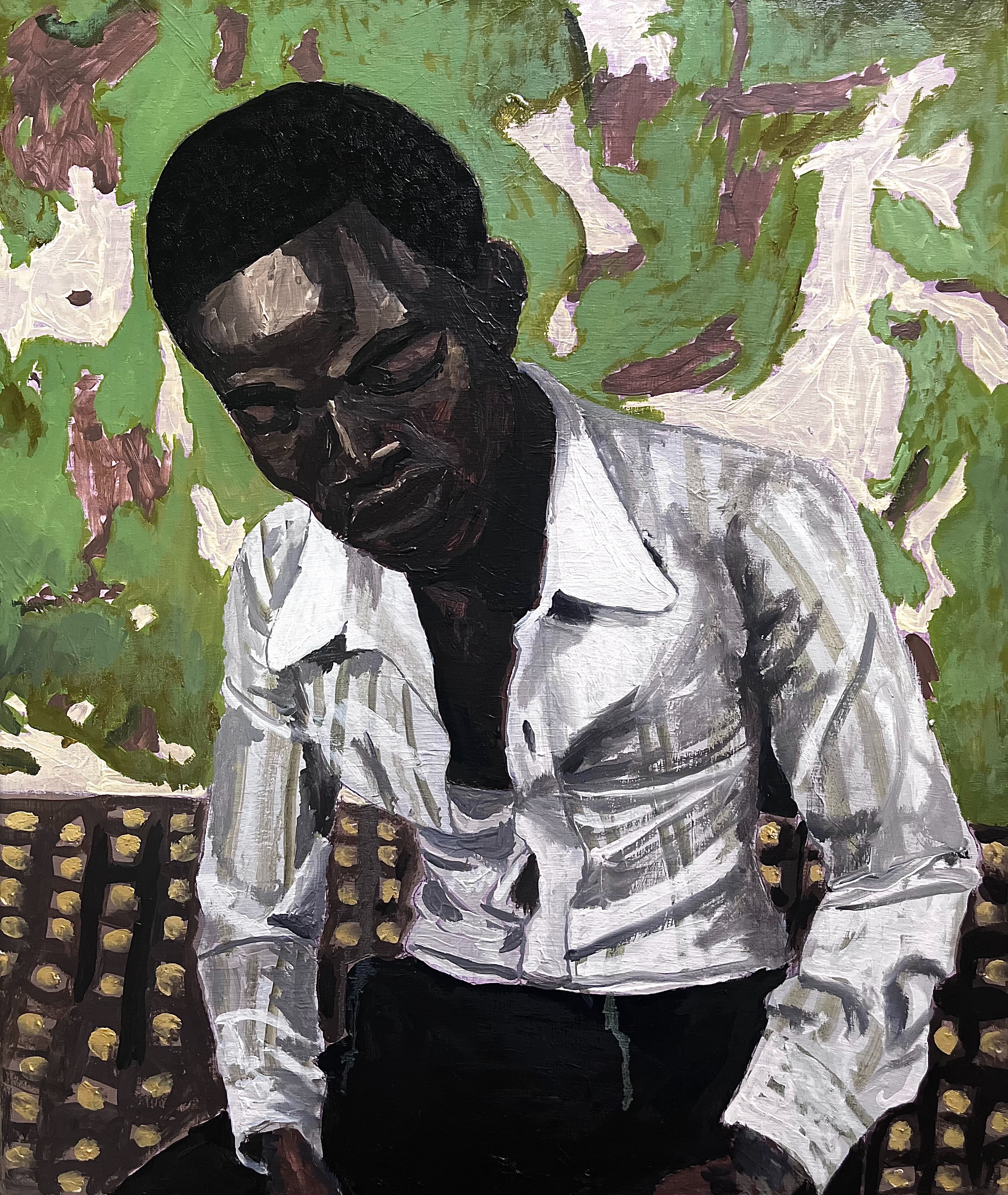

Artwork courtesy of Jakinda Boya

Long before film, however, there was drawing. Jakinda grew up copying Dragon Ball Z characters, taught by his older sister, and driven by a practical refusal of limitation. “I remember I wanted posters of Goku in my bedroom, but my parents wouldn’t buy them, so once I learned how to draw I was like, oh, I can just draw Goku myself.” He would take these drawings to school; classmates would gather around to look. “I remember liking that feeling — people looking at something I made. From then on, I kind of knew this was something I wanted to keep doing,” Jakinda muses.

Yet, the idea of art as a future was never straightforwardly sanctioned. “My parents were always against me studying art.” Jakinda explains and even at UCT, he began in a more conventional degree before trying, unsuccessfully, to move to Michaelis. Film became the compromise: “It was still creative, but it also felt like a real career to them.”

For a time, music seemed to offer a clearer horizon. Alongside Ayema, Jakinda’s work as Stiff Pap began to travel, and with it came a first, intoxicating sense that a life could be built from this. “I remember thinking, if I can get all the way to Europe just from music, then maybe this could be a real career,” he says. When Jakinda graduated, this is where he placed his bet. Then, the world stalled,and the forced pivots arising from the COVID shut down, short circuited the livelihood that music depends on: no shows, no touring, no rooms, no audiences.

Like many artists Jakinda found himself at home, suspended between making work and needing to survive. He kept working on music, but he also began drawing and painting again, returning to a practice that had always been there in some form. “I needed to make an income, and I was applying for jobs, but no one was really hiring. So I started posting my paintings online, and surprisingly, people started buying my work before I even believed this could work.” If there is an example of simply picking up a medium and committing to the work itself, Jakinda’s is it.

If music and film taught Jakinda how to work with others, painting has taught him how to stay with himself. Revelling in the solitude, he notes that both temperament and disposition, Jakinda is inclined toward interiority, and cultivating a rich inner world that can withstand the limitlessness of his creative expression.

“Music and film are so collaborative and they require working with a lot of people. I really love painting because it’s just me. It’s just me in my space, and I don’t really need to ask anybody what they think.” This notion, that the image must be pursued without negotiation or permission, is intrinsic to the archetypal solitude of the painter. From a technical perspective, too, painting has become for Jakinda the most open of forms as a medium; “I think you can do almost anything with painting in terms of creating an image, and when I look at the artists I admire historically, they’re all painters.” Even his relationship to the medium carries something of this headlong seriousness. He began with oil — “which is kind of crazy, because you’re supposed to learn with acrylic first” — and only later returned to it with intention.

Artwork courtesy of Jakinda Boya

Jakinda Boya photographed by Assante Chiweshe

Part of what made Stiff Pap so distinctive was not simply a sonic one; the project arrived as a total aesthetic proposition – performance, image, attitude, and fashion operating as one continuous register. Their visual impact was layered onto the music, and an extension of it — proof that sound, in our time, is almost always carried by image, and that cultural meaning now travels as much through how things look as through how they are heard.Such a penchant for aesthetics remains present in Jakinda’s painting, and we live in an era in which aesthetics are structural — in which fashion, in particular, has become a primary grammar for identity, a way of rehearsing who one is in public before one ever speaks. Jakinda’s paintings understand this fluently. “They’re not self-portraits,” he says, “but I think I’m creating characters — versions of myself, or versions of how you might see yourself in public, or how you see yourself in your head.” Fashion today, in an age of hyper-editorialised advert, is a phenomenal creative tool for constructing these figures. “I was very interested in fashion and style, so I started creating these stylish characters. Sometimes they’re very loud in terms of how they look, even though I don’t dress like that myself. I admire people who do. Even though the subjects might be stylish, the work isn’t about style or fashion,” Jakinda notes. They are containers for something else; namely experience, psychology, position. Each figure represents the extent to which Jakinda witnesses himself and those around him as expressions of the multiplicity of self, and this is perhaps the best argument I’ve heard for the psychoanalytic potential of fashion. “I mostly paint men because it’s closer to my own experience. For me, it’s that I’m trying to talk about my perspective and my experiences in Johannesburg.”

There is no conversion story in Jakinda’s account of becoming a painter, no single moment of decision that divides before and after. What there is, instead, is action. In the year of the fire horse, may we each heed this lesson! “I don’t know exactly when I decided this is what I want to do. I kind of just did it, and it started working,” Jakinda reminisces. The first signs were modest and practical: an open call at The Fourth, followed by a group show, resulting in a few sales; Jakinda notes, “I was like, okay, maybe I should keep doing this.”

The real engine for him remains the compulsion; “the thing about painting is that you get obsessed with it. You finish one painting and immediately you’re thinking, what’s next?” This loop — work leading to more work — is what turns activity into practice. And practice, for him, is inseparable from respect. “I also really respect the craft. There are people I admire who are much better than me, and I don’t want to do this badly. I want to keep doing it so I can get better and take it seriously.” You begin by doing, you continue by staying, and you earn the right to be here by working; these are lessons from the interiority of a painter’s life.

Looking ahead, Jakinda sees the next year as a space in which to do even deeper work. “I want to start doing residencies. I think I’m at a stage now where I have a better understanding of what I’m doing, and I want to put a cohesive body of work together, like a proper series, and have a show.”. He wants the work itself to shift, noting that “I want my work to start changing. I want it to become more about mood and psychology — more about what it actually feels like to be someone in Johannesburg in our time. Even if the characters still look stylish, the work isn’t about that anymore. It’s about something deeper.”

Jakinda returns, finally, to the idea of practice as something unfinished and ongoing. “I’m constantly developing myself. I think it’s a lifelong practice. There’s a feeling I’m chasing in my work, and that’s how I know when the work is finished. I can’t really describe what that feeling is, but I know when it’s there.”

Somewhere in that pursuit sits a desire to fold his earlier languages back into the present one. “One day I want to incorporate my film background into my art. Maybe through a residency, that’s where I’ll explore that.” But ambition, for Jakinda, remains tethered to humility and to a serious engagement with the lineage of oil painting itself — even as we live in an age that increasingly rewards cross-disciplinary fluency. Jakinda is already fluent in more than one language of making, and even if Stiff Pap were the only thing he had ever made, it stands as a cultural contribution of immense weight. Life is short and the days are long – when art is your birthright, the work does not end and the call remains unending.

Written by Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za