Water is our oldest ancestor. Long before life emerged on land, the earliest oceans unlocked cellular expression; it was in these ancient waters that life first learned to organise, to metabolise, and ultimately, to become. Only much later did this aquatic intelligence climb onto shore, carrying the memory of the sea inside every cell — nearly three billion years later.

Across cultures, it has been understood as origin and threshold, from Nuwa’s dominion of the celestial waters in Chinese mythology, to the Ganges as a purifier and passage, or the Nile as giver of life and civilisational rhythm, and the mythic, meandering Styx as boundary between worlds; the rain-bringers and flood-myths that appear in almost every cosmology. Jung wrote of water as the most common symbol of the unconscious — of the primordial waters from which life, memory, and psyche emerge — and of the way its depths mirror the depths of the inner world. Its psychological, energetic and physical implications are tethered to our existence in ways we cannot even begin to truly articulate.

Here in southern Africa, among San and Khoikhoi traditions, water is a living presence — often associated with what is called n/um, a vital force linked to rain, storms, and certain water places. Water is a keeper of memory, a site of spirit and healing, and a source of both survival and story — something one is obligated to listen to, follow, and honour.

Adele Van Heerden is an artist imbibed by water; it is her medicine, her mirror, and her method. Soaked by bodies of water both literal and imagined, and working within the conceptual terrain of her current solo show Alluvial, Adele notes to me that she has sought refuge with Marchelle Farrell’s work Memory River in the collection By The River: Essays From The Water’s Edge, using it as a textual anchor for her thinking about rivers as both material and metaphor. Marchelle writes: “Memory flows like a river, and it is through its constant flow that we come into being. We live in the moment: the ever-changing, ever-forward-rushing current of now. The flow of experience, once retained, constantly reshapes the land of self through which it courses, forming bedrock and depositing the mud of new, fertile ground. A featureless plain becomes a richly textured topography of ridges and valleys, cliffs and plateaus, clothed in earth in which all manner of relationships can take root.”

Of water, Adele is a lifelong student. “I’ve always loved water — I’m a swimmer,” she says, “but the real turning point was after a hip injury and surgery, when I had to rehabilitate in the pool.” From recovery, to healing and now an inextricable, ritualised aspect of her life, Adele’s almost singular focus (with endless, generative threads) on the aquatic as a field of feeling is grounded in her artistic practice, and her ongoing practice of swimming. “I started swimming every day, spending hours in the water. It really got under my skin, and slowly made its way into my paintings.” After her surgery, being in the water was no longer just exercise but “a way of relearning how to be in my body,” an experience that, Adele says, changed how she sees herself and how she moves through the world.

Adele’s relationship to art is inborn, as is her affinity for water, and she shares that it was an instinct deeply encouraged. “For me, it was always an inherent knowing that I was an artist,” she says. “I was very lucky — my family was incredibly supportive, and I was always going to art lessons. So when it came time to decide what to study, it just felt completely natural to choose fine art.”

Her path was both rigorous and wide-ranging – Ruth Prowse, then UNISA, where she studied history, art history, and politics, and finally UCT’s honours curatorship programme. “That last year really pulled everything together — the practical, the historical, the theoretical,” Adele reflects. It is precisely this synthesis that makes a fine art practice so compelling; the work of making, and the work of thinking, held in equal measure.

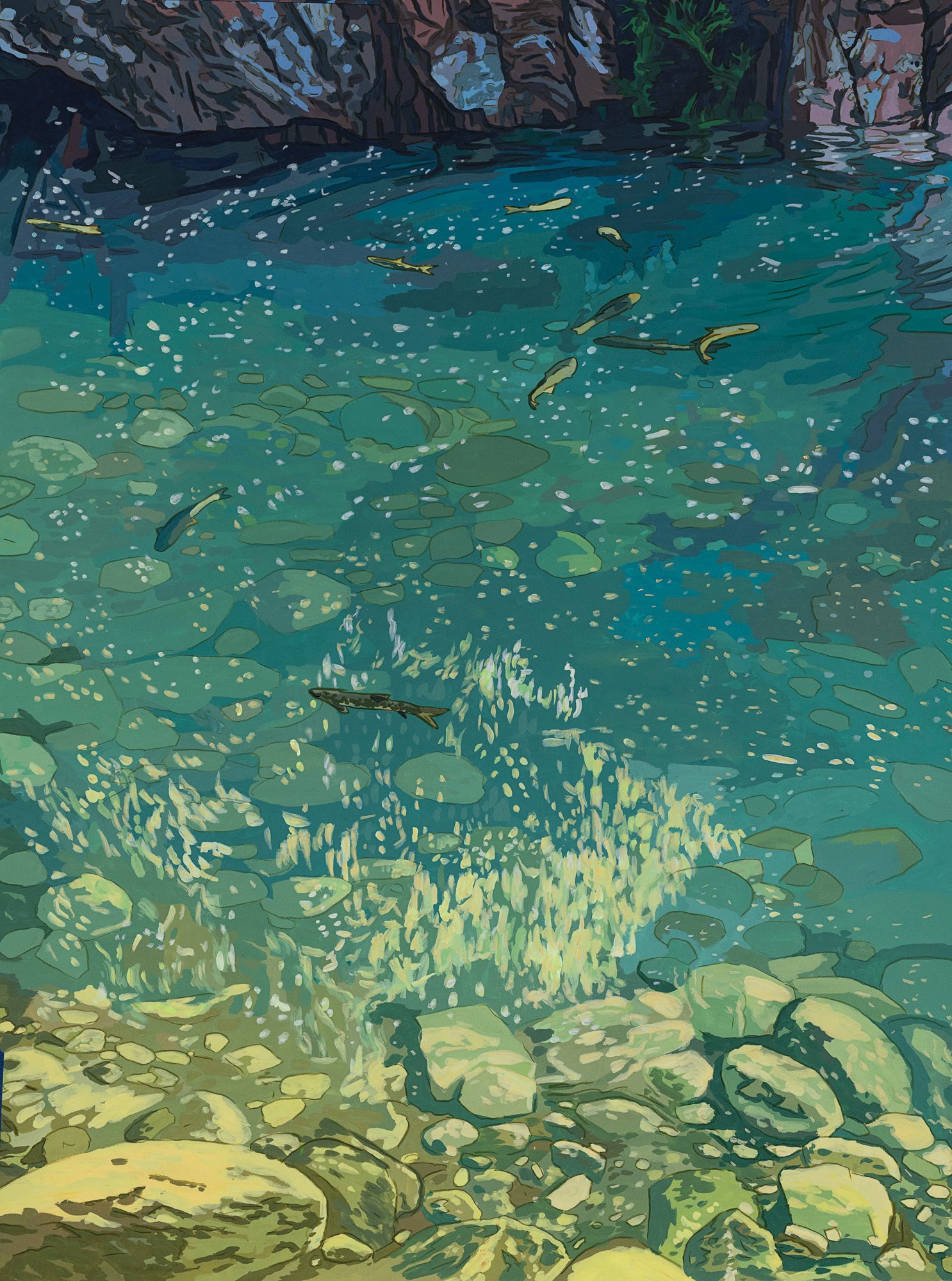

Adele van Heerden – Memory River, Pastel and Gouache on Film, 60x42cm, 2026

Adele van Heerden – Water Meadows II, Pastel and Gouache on Drafting Film, 60x84cm, 2026

Adele van Heerden by Olifants-Doring River. Portrait by Lauren Thomas.

Adele’s distinct style might be described as contemporary figurative painting with a graphic–impressionist sensibility; signature flattened planes of colour, held within a strong and deliberate graphic structure. It is the rigorous and disciplined drawing practice she developed at Ruth Prowse that she credits when I ask her where this visual language comes from, and that “when I was younger, I was very interested in animation and cartoons and anime. I think that world — the way things are simplified, flattened, stylised — really stayed with me, even before I knew it would become part of my painting language.”

With the technique itself, Adele explains that it is entirely her own; “The style people recognise me by is something I developed myself. I work with pastel and gouache on drafting film — the translucent, milky paper architects use. I’ll draw on the front, then turn it around and paint on the back, so it becomes a kind of reverse painting technique.”

It is this unusual process, she says, that produces the distinctive flatness of her images, noting that “that’s where the flattening comes from — these fields of colour, these flat planes. It’s partly the material itself that creates that effect.” Recently, though, Adele’s practice has begun to open into new territory. “Lately I’ve also started painting on the front and working more on canvas, with gouache, acrylic and oils. It’s becoming more painterly, but it still feels very much like my eye and my language. It’ll be interesting to see where it goes next.”

Returning to water, it becomes clear that this relationship is an elemental way for Adele to understand herself. To water, we can give our dreams, our tears, and our desires for cleansing; and as Adele explains, water has become a deep container through which she reflects her identity back to herself. “Recently I came to understand that I am queer — my identity is fluid — and with that realisation came an expansion of both self and practice. My pieces often become small inside jokes and ongoing conversations with myself, as I explore what lies beneath but is rarely seen.”

In this sense, water is Adele’s reflective surface for her questions of identity, visibility, and inner life. “I started thinking about fluidity — about seeing water as a kind of teacher, and asking what it could reflect back to me. There was definitely an internal transformation that came from that. Water can be ice, it can be fluid, it can be vapour. I try to think of myself like that too — as having no fixed identity, always in a process of change. Water feels like a kind of container for me — a space where things can change form, where nothing has to be fixed or final,” and that, “I don’t like to put too many external definitions on myself. I try to move with the ebbs and flows of life, and do what feels authentic in the moment. I think of myself as fluid — always becoming, never fixed.”

Before Alluvial, Adele’s attention had been held by swimming pools and oceans — by contained bodies of water and open horizons. The shift to rivers and mountain streams marks something of a turn toward water as a force that moves through land with impact and geological consequence. “After that, I started spending more time in the mountains — walking, hiking, being around streams and rivers.” The project began around eight months ago during a visit to the Olifants-Doring River in the Cederberg, where she encountered the glimmering Clanwilliam Yellowfish. “According to my gallerist, these fish — which only occur in this river — were once on the brink of extinction due to the introduction of alien species like bass. The river was fully rehabilitated a few years ago, and the Clanwilliam Yellowfish have now returned to a healthy population. I felt compelled to draw them, warped and flattened by the water, with rocks and sediment beneath.”

Alluvial refers to that which is formed by deposition — the slow, patient laying down of material by water over time. In this sense, Alluvial is a study of water, but equally so of time, pressure, and accumulation. “Many people associate ‘alluvial’ with gold found in rivers, but in the context of my work it refers to what can be found in layers of soil, muddy water, and bedrock.” The river, for Adele, is a choreography of erosion, deposition, and revelation. “Suddenly our weekends became about finding mountain water — rivers, streams, rock pools.” There are so many beautiful walks along rivers here.” What Adele is tracing, it seems, is what water gathers, what it carries, and what it leaves behind as it moves.

In South Africa, Adele notes, mountain water behaves very differently from the blues of pools or oceans. “It’s often brown or orange because of the tannins and the soil,” she says, and it is precisely this complexity that has begun to hold her attention. “I became very interested in how water behaves in a mountain stream, how it moves around rocks, how the sediment and bedrock form these layers. There’s always this question for me; what’s underneath the surface? What remains hidden? What can we really see? I started thinking about time as a river — this constant forward movement. You can’t stop it, you can only move with it.”

“That moment when you can finally see the path forward is incredibly satisfying,” Adele says, of arranging her sights on a body of work for solo shows. Her exhibition Alluvial, currently on at 131 A Gallery, is the result of precisely this kind of intuitive search. For her, the solo show is a process of discovery. “What I love about a solo show is the chance to really dive deep. It’s a very intuitive process — I’m often trying to find out what the work is trying to tell me. Preparing for a solo can take six months, a year, sometimes longer. It’s a slow inquiry, and I often describe it as being in a dark forest, trying to find my way. You feel a bit lost, but you know the direction. And then suddenly you reach a clearing — and everything becomes clear.”

Adele van Heerden – Becoming, Oil and Gouache on Canvas, 84x60cm, 2026

Adele van Heerden, portrait by Paris Brummer

Adele van Heerden – Alluvial, Pastel and Gouache on Drafting Film, 60x84cm, 2026

Looking ahead, Adele speaks about a year shaped as much by movement as by making. “This year I’m going on residency at NIROX in the Cradle of Humankind, which I’m very excited about.” She is also planning a trip to Scotland, “I’m going to look at the lochs,” Adele says. “I think it’s important to go out into the world and experience things — it all feeds back into you and your work.” I remark on how rare and beautiful it is to locate one’s travels and curiosities through bodies of water — to move through the world by following rivers, lakes, and deltas. Adele muses,: “I often think about my movement through the world in relation to water — which rivers I want to see, which bodies of water I want to spend time with, how cities are shaped by them.”

Adele’s work is devotional to nature and in nature; an exaltation, through her own attentiveness, of the many boons and blessings that await us on this planet, unconstrained by limitations or constructs. “I’m always in search of moments of awe — in my work, but also just for my own being. I think finding awe in nature is one of the great lifesavers.” In this sense, Alluvial is a way of learning to read the world, layer by layer, and of its great teaching, Adele notes that, “I think the great teaching of Alluvial is that there’s always gold to be found — if you’re willing to take the teachings.”

This is in no way a story of gold and conquest, no, Adele’s work, and Alluvial, are reminders that the most precious minerals are the kind that only appear when you are willing to follow the river; to keep looking, and to let yourself be changed by what you find.

Alluvial is now showing at 131 A Gallery until 2 March.

131 Sir Lowry Road, Cape Town

Written by Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za