Published bi-monthly, Art Themes presents a thoughtfully curated selection of artworks shaped by a unifying conceptual framework. For this edition, the focus is guided by the arrival of February’s zodiac inauguration for 2026, marking the beginning of the Year of the Horse—a symbol rich in cultural, historical and artistic significance.

In April 2023, the artist-led gallery space ‘Under Projects’ curated Paintings of Horses, an exhibition that encouraged artists, peers, and friends to follow a simple, almost disarming prompt: paint a horse. The results were immaculately playful, feverishly fun, and deeply revealing.

In that instance, the subject was linear—and contrary to many of our previous ART THEMES editions, that same boundary is what The Year of the Horse encourages here. Sometimes, especially at the start of a new year, constraint can be liberating. A single subject becomes a shared point of departure rather than a limitation.

Horses have long mesmerised and enchanted humans, and for good reason. From the cave paintings of four horse heads found in Chauvet, France, dating back to around 30,000 BC, to contemporary literary reflections such as Blood Horses by John Jeremiah Sullivan, the horse appears again and again as both companion and conquest.

Sullivan captures their indignities and our own—acknowledging how we exploit them while still finding deep beauty and meaning in their power and our connection. He asks, “what frightens us is the idea that we have triumphed over nature, and what that triumph will mean.” It could be argued that no other animal has shaped human history quite as profoundly. The horse carried us into war, across continents, into agriculture, industry, myth, and empire. In many ways, the horse made us who we are.

It is with this historical, emotional, and symbolic weight in mind that we present an indulgent dive into contemporary artistic representations of horses—works that explore the animal not only as form, but as metaphor.

‘The Reign’, Sculpture, 2010

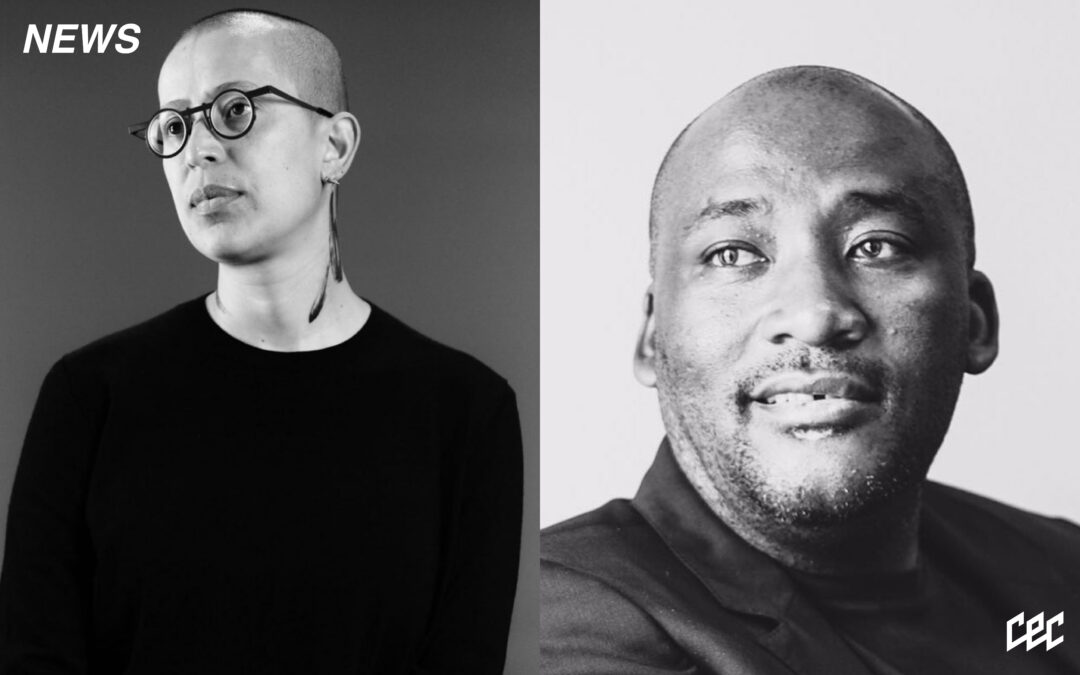

Mary Sibande is a major contemporary South African artist whose work explores identity, race, gender, history, and power through highly theatrical sculpture, photography, and installation. Central to her practice is Sophie—a life-size alter ego modelled on Sibande’s own body, rooted in the lived experiences of the Black women in her family.

While Sibande’s practice is not exclusively centred on horses, her use of equestrian imagery is intentional and deeply symbolic. Historically, the image of a figure on horseback has been reserved for monuments of power—military leaders, conquerors, kings—overwhelmingly white and male. By placing Sophie atop a horse, Sibande reclaims this visual language, repositioning a Black woman within a space of authority, command, and imagination.

The horse becomes a vehicle for re-writing history. Sophie’s origins as a domestic worker—signified through uniform and posture—are placed in direct tension with the grandeur and dominance of equestrian portraiture. In doing so, Sibande collapses past and future, labour and leadership, subjugation and sovereignty. Her horses are not symbols of escape alone, but of earned presence, agency, and reclaimed narrative.

Photography courtesy of the artist’s website and Instagram archives

Ian Grose

‘Clara’, oil on canvas, 2024

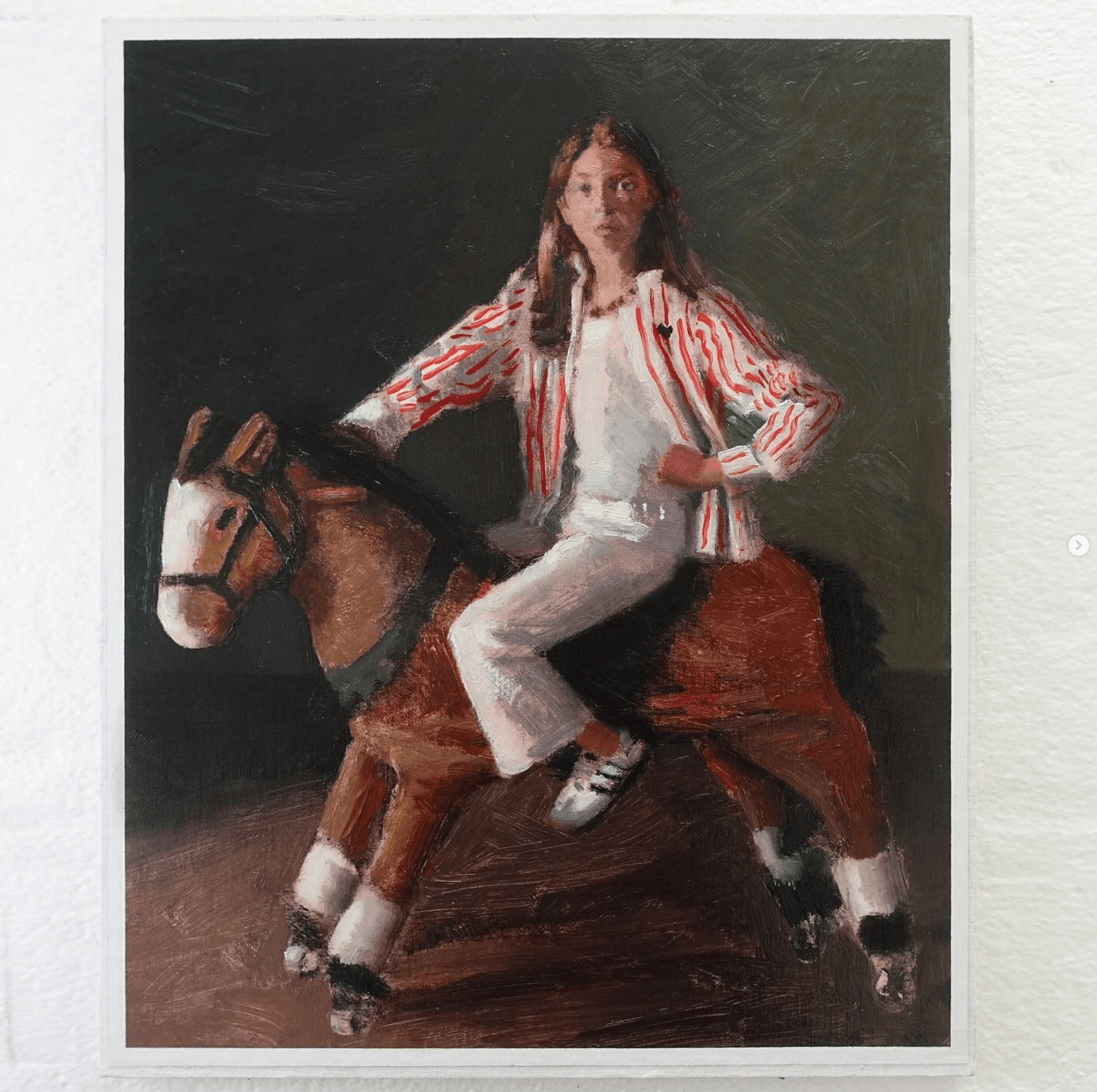

Invited to Mexico City by a collector to undertake a series of commissions, Clara reflects a transient yet intimate period in Ian Grose’s practice—sitting in strangers’ homes, painting while his subjects watched, and absorbing the quiet psychology of unfamiliar domestic spaces.

While Grose is best known for his portraiture, the inclusion of the horse here subtly expands his interest in presence and vulnerability. Rather than depicting the horse as spectacle or motion, Grose renders it as still, almost contemplative. The animal becomes a counterpart to the sitter: grounded, watchful, and emotionally charged beneath its surface calm.

In the context of The Year of the Horse, Grose’s work speaks to the quieter dimensions of the zodiac sign—endurance, patience, and emotional intelligence. The horse is not galloping forward, but waiting, holding space, bearing witness.

‘Blazing Saddles’, Oil on canvas, 160 x 130 cm, 2024

Jan Możdżyński’s practice spans painting, drawing, objects, and video, and is rooted in an exploration of sexual identity, gender performance, fetish, and power. Drawing from BDSM iconography and role-play, his work destabilises traditional understandings of masculinity and femininity.

In Blazing Saddles, the horse becomes a charged site of projection—intertwined with eroticism, control, vulnerability, and fantasy. Historically associated with virility, conquest, and masculine dominance, the horse in Możdżyński’s work is re-coded. It exists within a theatrical, unstable space where power shifts and identities blur.

Here, The Year of the Horse is not triumphant, but provocative. The animal becomes a vessel through which social expectations collapse, revealing desire as fluid and performance as political. The saddle—traditionally a tool of control—becomes symbolic of negotiation, consent, and role reversal.

‘One Day I Will Leave You No.1’, Acrylic on canvas, 2021

Born in China and currently based in New York, Yirui Jia is an MFA Fine Arts candidate at the School of Visual Arts. Her work is populated by exuberant, cartoonish characters—anthropomorphic animals, objects, and figures drawn from popular culture and personal memory.

In Jia’s universe, horses are not monumental or heroic, but emotional and narrative-driven. They exist as companions, symbols of longing, transition, and growth. The title One Day I Will Leave You introduces themes of departure and independence—ideas deeply resonant with the zodiac meaning of the horse as a sign of movement and self-determination.

Jia’s playful visual language softens the weight of these themes, allowing humour and tenderness to coexist with melancholy. Her horses are less about dominance over nature and more about navigating emotional landscapes—leaving, becoming, and learning how to move forward.

‘2026 The Year of the Horse’, oil on canvas, 2026

Born in 1992 and based in Valencia, Ricardo Rodriguez Cosme paints horses and cowboys with a classical hand and a distinctly contemporary sensibility. His work interrogates masculinity as image—branded, performed, and emotionally restrained.

Cosme’s horses are inseparable from the cowboy figure, yet neither is romanticised. Instead, they exist in states of loaded stillness. These are not action scenes, but moments suspended in time. The horse becomes an extension of masculine identity—disciplined, beautiful, controlled—while quietly suggesting tension beneath the surface.

In the context of The Year of the Horse, Cosme’s work speaks to inherited myths and their quiet unraveling. The cowboy, once a symbol of freedom and frontier conquest, is reframed as icon rather than hero. The horse, too, is no longer merely a tool of movement, but a reflective surface for emotional restraint, vulnerability, and cultural expectation.

Photography courtesy of the artist’s website and Instagram archives

What became most striking throughout this research was how, much like Under Projects’ original prompt, there appears to be a global, almost instinctual pull toward the horse in response to The Year of the Horse. Across continents, cultures, and practices, artists return to this animal as if answering a shared call.

This collective engagement signals more than coincidence. The horse is an accessible yet profound subject—one that carries with it centuries of human history, labour, mythology, and emotion. It evokes our relationship to nature, our desire for progress, and our ongoing negotiation with power and freedom.

It feels fitting that artists return to an animal that once carried us forward—physically, culturally, and symbolically. Through paint, sculpture, and narrative, these works remind us that the horse is not only part of our past, but an enduring mirror of who we are, and where we are headed.

As 2026 unfolds, ART THEMES || THE YEAR OF THE HORSE invites us to move with intention, to honour momentum without forgetting stillness, and to recognise that sometimes, the most ancient symbols are the ones that help us imagine new futures.