There are aspects to ecological life that are considered taboo. In our Western context, concepts of decay and decomposition are viewed as the final, horrifying states of matter that need to be avoided or sanitised. Yet, from an ecological perspective, these processes are foundational to life itself; enabling organic matter to return to the earth, nourish soil, and support the growth of new life. In this sense, decay is not an end; it is critical in the cycle of regeneration and renewal. We owe much to the beautiful force of rotting. It is precisely within this borderland; between life and death, beauty and decay, growth and entropy, that Georgia Munnik’s artistic practice is situated. The launch of her perfume, PHENOTYPE 13, is the culmination of an olfactory practice that uses alchemical process and ingredient cultivation, with the outcome being fragrances that explore ecological and cultural histories. This is the latest in the highly articulated, tonally rich world that Georgia has been building for some years.

“I chose to study art after high school and got into the fine art program at Wits, which set my direction,” Georgia recalls, and “I was quite rebellious for the first two years — I hated the prescriptive, systematic ways of learning. Everything felt so rigid in the first and second years. But by third year, we were able to take on our own projects, and that’s when I really flourished. I’m lucky; I’m one of the few who didn’t end up completely put off by art school.” Wits School of Art had a strong focus with a conceptual, immaterial approach and although, “in my third year, I was already interested in decay and materiality in my work,” she says, “I remember being encouraged toward video, performance, and writing — which I was naturally strong in.”

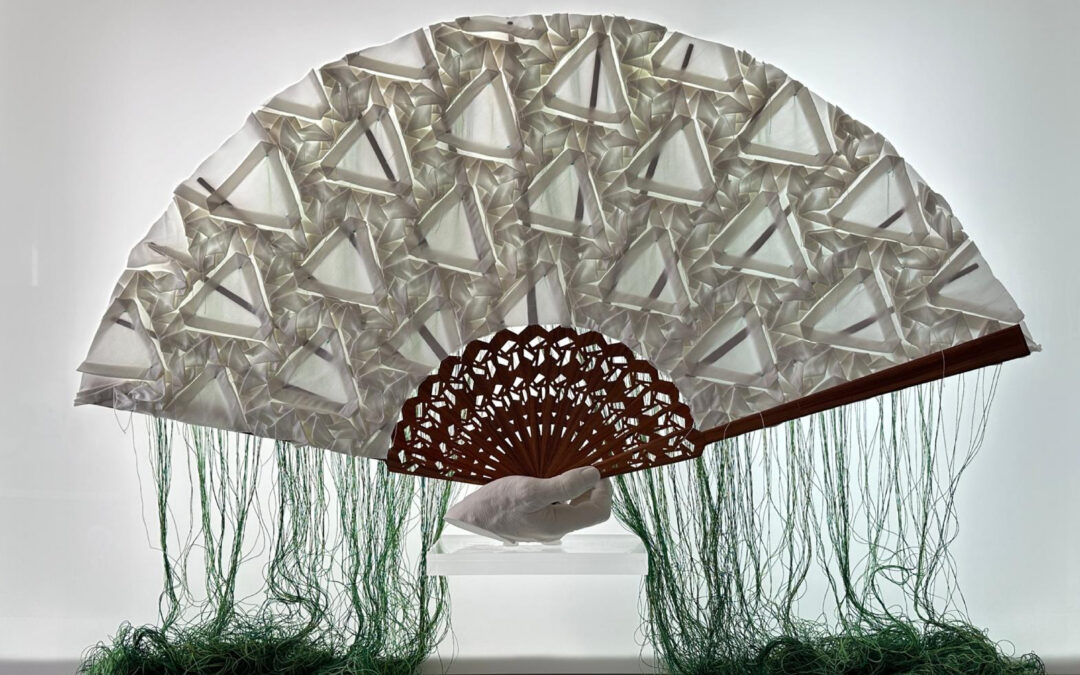

AKJP window sculpture, photography by Theodore Afrika

Portrait by Theodore Afrika

It wasn’t until Georgia’s Master’s at the University of Tromsø, an amazingly funded and entirely hands-off art school in Norway’s isolated and almost otherworldly northern region (at the precipice of the Arctic) that things shifted. “I was really interested in language at that stage — translatability, especially. Being in a different context, I started examining my own country more politically, even creating pidgin languages, like a pidginized Norwegian, for my video practice. It was funny; I always felt I could best express myself visually if I was working toward an exhibition.”

“After a series of unexpected turns, I returned to South Africa after four years in Norway,” Georgia shares. “I was lucky enough to get a residency in Basel, which became a huge turning point for me. I realised that as an artist, you have to constantly advocate for your material practice, and to find a reason to make work beyond. I was alone there for two months — just me and a lot of Swiss cheese,” she laughs. At this point, Georgia turned to flowers as a salve for this moment and, “during that time, I started laminating flowers. It was so simple, but I realised I needed to build a world around myself.” Flowers hold a mystical place in the human imagination; we have engaged in flower burials for thousands of years, and it is theorised that this practice was an aspect of Neanderthal culture, suggesting they engaged in symbolic or ritualistic behaviours long before us modern humans. Archaeologists discovered evidence of this practice at the Shanidar Cave in Iraq, where Neanderthal remains dating back around 65,000 years were found buried with pollen from various wildflowers. It is almost as if the sheer fragility and ephemeral nature of flowers instinctively tell us something about ourselves: embodying something that is simultaneously beautiful and utterly devastating. This connection to flowers may be as innate to the emergence of hominids as our ability to stand upright.

Photography by Theodore Afrika

Mario Todeschini “How Do You Mourn”

“I was mourning having to leave”, Georgia explains, and “I’d been deported due to VISA issues, and I’d just ended a relationship. The connection I had to those places and memories were tied to flowers, so I collected poppies, cornflowers — all specific to Northern Europe. It wasn’t even about making art; I just wanted to make my space beautiful.” Until this point, as Georgia shares, her work was in relation to the institutions and frameworks in which she participated. From the simple act of laminating flowers – asserting her own aesthetic motivation, to reckoning with her own lived experience and internal state – a transformation occurred all at once; “I had this strange dream around that time. I was in a lecture and asked a question, and before answering, my lecturer asked me to list the ways I mourned. So I did, and it was incredibly revealing. It got me thinking about laminating flowers in a more political way, and what ‘sustainable mourning’ could mean.” This introspection led her to continuation of this thread at her next residency at Fabrikken in Copenhagen.

“At Fabrikken, they were incredibly supportive and wonderful,” Georgia reflects. “I stayed with my best friend, who is deeply into eco-feminism and introduced me to amazing eco-feminist authors and literature, like Anna Tsing’s ‘Mushroom at the End of the World’. This experience brought me closer to my immediate environment and influenced my work profoundly. I decided to laminate a bunch of yellow roses, taking them apart and completely reconstructing them. What emerged was this wild schism, almost like something out of a sci-fi narrative. From that point on, everything changed for me. Since 2019, my practice has been firmly rooted in that realm — it felt like I opened up a portal!”

Personally, I am a big fan of death and decay. I once heard someone say, ‘death is a huge opportunity,’ — and this reframing, of death as a starting point, is entirely a subversion of the doomed place it holds within our western minds. I think of the Tibetan Buddhism practice called ‘chöd’ founded by the female saint Machig Labdrön in the 11th century. Chod, which translates to ‘cutting,’ is a direct, meditative confrontation of death – in which practitioners engage in visualisations where they offer their own bodies as food to malevolent spirits and demons, symbolically cutting the binding ties with attachments to life and the reluctance for change. Georgia explains that, “the decay was really interesting because I really was making biodomes by laminating fresh roses. They would start to develop microcosm of mould within that epidermis; the plastic skin over the petals would create this tiny world, until they would get suffocated out. That made me think about our bodies being completely porous. This was happening during the pandemic in which we were villainising a virus, but our bodies are referred to as the human microbiome; we are made up of 100 million viruses. I was thinking about decay as an opportunity for more life, and mushrooms and mycelial networks.”

Speaking to Georgia, I am reminded of the strange comfort, even in the face of existential threats like the Anthropocene — a period defined by our significant and overreached human impact on the Earth’s geology and ecosystems — in knowing that we are ultimately organic matter at the mercy of organic and geological processes. This reality is our intrinsic connection to the natural world; creation and decay govern our existence. It is utterly poetic. Georgia notes that, “I love the way Donna Haraway, the famous science and feminist writer, frames it – that the Anthropocene is a boundary event between now and what is possible afterwards, especially when we finally give in to the inevitable of our bodies being part of nature. What are the new stories that we can start to tell about the epoch to come afterwards?”

On the medicine found in the purposes of decay, Georgia utilises biological processes and the composting of matter as a reflective tool to address psychological processes—like grief and mourning—and the way these are necessary functions from which we should not look away or turn away from. “I taught a workshop in Aalborg, Denmark, where I explored mycelial communication, and discussed how mushrooms communicate through their mycelium, a vast underground network that allows them to share nutrients and information. The fruiting bodies of mushrooms, which are one of the many forms of reproduction, literally pop up to fulfil their purpose of rotting and decaying, enabling the dispersal of spores, and thus new life.”

Georgia’s deeping and layered focus on death, life and procreation have formed the backbone of her practice — now, she is currently in the proposal phase for her pHD at Stellenbosch University, under Kathryn Smith and Ernst Van der Wal, and shares that “the whole project is around the apartheid-founded museum system as a decomposing body. In thinking about the post-apartheid era, how do we mourn this history that we all share? I’m proposing for specific museums to become sites for mourning, death and decomposition. My paternal family history museum, the Anderson Museum in the Eastern Cape, is this insane institution that is essentially starting to rot, fall apart and deteriorate. That’s basically the premise of my interest in rot.”

“A friend of mine, Chanel Adams, is a writer pursuing her PhD in geography in Switzerland. She shared an intriguing story about a ceremonial bone practice in Madagascar. In this tradition, when someone dies, their body is kept in trees until only the bones remain. Years later, there is an entire practice that involves dancing with these bones, celebrating the decomposition of the body and truly witnessing the natural process of decay,” Georgia shares, and once again — I am drawn back to Tibet, specifically the ‘Sky Burials’ tradition in which dead bodies are laid atop mountains for the vultures to consume; as an offering back to earth, the elements and the ecosystem in which the body once inhabited.

I ask Georgia about her segue into an olfactory practice; “I’ve always been interested in scent and it had been part of my practice previously, but the seminal moment I think was in Copenhagen and my best friend’s friend arrived, he’d beene cycling and was all sweaty, but he smelt insane. He explained that he was wearing Amouage Interlude. This was my introduction to perfume in a deep way — it was like diving into a resin-filled forest, and I realised that perfume is truly made for our body, especially the way it interacts with our pheromones.”

Two years ago, Georgia was awarded the Rupert Museum Social Impact Prize for a residency in Graaff-Reinet, where she collaborated with Louise Johnson on a relational history project. They aimed to explore how to convey difficult histories in a way that is more accessible and less challenging to consume. “Do you tell it through the senses?” Georgia reflected, “this question led me to work with scent as a medium for addressing the complexity of shared histories,” and with guidance from her mentor, Dave Pepler, she began hand-cultivating ingredients to create her own absolutes, such as oakmoss, which is lichen taken from olive trees. As an ecologically-driven, somatic scent practice, Georgia asserts that “scent is a biological tool, and we understand things about ourselves and our environments from the odours we emit or smell. Perfume is also such an exploration of the body and sensuality.”

With her recent launch at AKJP, PHENOTYPE 13 ‘pays homage to the poetics of scent as an expression of nature.’ I ask Georgia why, then, she opted to extend her practice to a product – often seen as a commercial and reductive outcome to the way in which fine artists should forge a material practice. “I’m so over the gate-keeping in the fine arts,” Georgia explains, “the most generous thing you can do is make your work accessible. So the idea was to make something that was not as expensive as my visual art, and that was also consumable. Smell becomes deeply personal for everyone, so I want my practice to touch people and for people to really, sensually engage with it. It’s complete alchemy and witchcraft.”

On the layered notes of the scent itself, Georgia explains some of its aspects; “the composition of PHENOTYPE 13 is built around a base note of cannabis that I hand-cultivated. There’s Oud Assan, which has a very hay-like quality, and then I included octyl acetate, a synthetic scent that resembles moulding fruit and has a distinctly mushroomy aroma—so I had to add that. Oakmoss contributes an incredibly earthy scent, reminiscent of digging into fresh soil. You let it sit, almost like a fine wine, and there are chemical processes that occur after I make it that have nothing to do with me. There’s also amber accord, which is fascinating because it’s a synthesised scent and yet it’s one of the most luxurious, prized ingredients in perfumery—nothing in the world smells quite like it.”

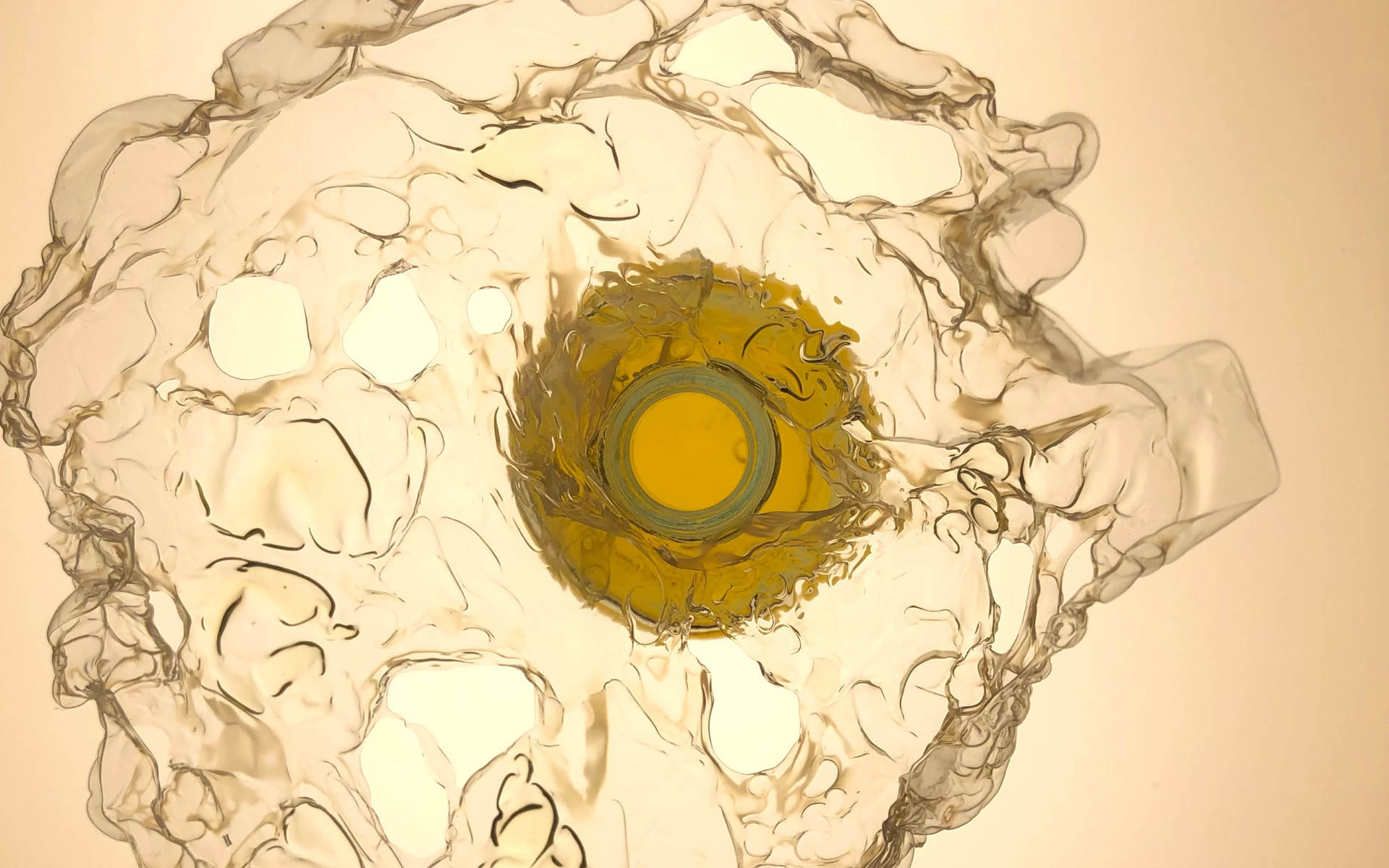

Available exclusively at AKJP, PHENOTYPE features three original prototype artworks and six more uniform pieces, crafted with gold-leaf plated, blue-dyed rose petals embedded in resin, and ‘each bottle serves as a personal sculpture for the wearer and is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity.’ The three sculptures, each distinct in their expression of Georgia’s interest in the localised, Western Cape ecology, are undulating expressions of material, form — and encasing life and death, such as the one that features trapped black mould or the body of moth, the latter found by Georgia on a walk in West Coast National Park. All that Georgia touches – alive or dead – is intended for exhalation through her own essence, and vision or the way in which the sensorial aspects of reality should be experienced and it is totally enthralling and mesmerising. “Once I start on something, it has to be exceptional. I had a private commission that involved resin, so I was already working with it as a material. I developed a prototype series of bottles, and I realised through my journey of mourning that I need people to witness me. I need them to witness the process, and that’s how I emerge transformed. So, I approached Claudia at AKJP, and I was amazed at their willingness to collaborate with an artist. Claudia really pushed the material outcome of the bottles and helped me shift my perspective away from viewing it as a commercial project. Then, I just went wild.”

Lastly, I ask Georgia whether scent will be part of her path now — to which she assures me that she’s already working on a new series, “I have to! It’s selling and I’m getting such good feedback. I think it will be a bit more simplified. It’s also my business now, which is amazing to be as an artist; I want something that feeds me economically and that also feeds my soul, and I want to be in charge of that.”

Written by: Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za