It has become commonplace in creative spaces to identify people as multidisciplinary — and almost always, it rings true. If we uncover its meaning, to be ‘multidisciplinary’ means to be engaged in an approach that combines knowledge, methods, or perspectives from multiple viewpoints, harnessing such combinations towards a said work or practice. An interesting thing happened while I sat in conversation with artist Unathi Mkonto; I realised that perhaps I was engaged with someone who might be truly totemic in embodying the stripped back essence of multidisciplinarity.

Unathi, after all, is an artist by virtue of having been a trained architect first, a fashion designer second and finally, arriving at his current practice when it was clear that all of his instincts to create were perhaps better suited to the unrestricted and (generally) non-commercial confines of gallery spaces and museums. Before Unathi sculpted, he did many things — all the while the practice of drawing has accompanied him since childhood. As Unathi reveals in our conversation; everything that has ever piqued his interest and held his attention becomes continual in his work. Cohesion of intellect and physical making are always, always key.

On his earliest awareness of the pull towards expression, Unathi reflects that, “I grew up in a small town in the Eastern Cape – Peddie – where there wasn’t a presence of buildings, it was just open landscapes. I always had an interest and a need to create things and I started drawing buildings in primary school,” and that, “by grade four, I already had stacks of books filled with drawings. While other kids were drawing action heroes, I was drawing buildings. I knew I wanted to be an architect from that age. I think I was driven to create something that wasn’t present in my immediate environment, along with the isolation of growing up in a small town.”

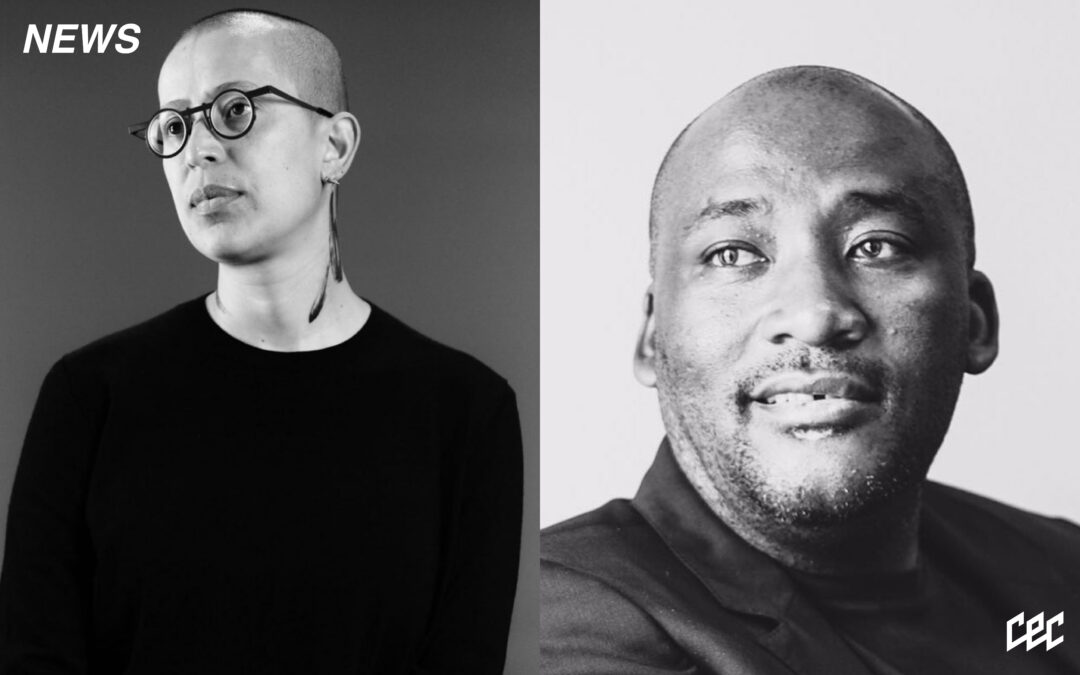

Photography by Luke Doman

Photography courtesy of Stevenson Gallery

Unathi’s impulse towards the built-environment led to his completion of a BA in Architecture from Nelson Mandela University in Gqeberha. This impulse, so strong and innate for Unathi, is reminiscent of French philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s position that architecture and the spaces that we inhabit occupy an intensely poetic dimension for – whether we consciously or unconsciously know this – reflections of our inner lives. Unathi has followed this thread until today; even when the traditional form of architecture was no longer sufficient to describe his emerging viewpoint. “I think architecture is in everything,” says Unathi, “It is embedded in our daily lives — from portrait to landscape, to inside rubbish bins. It’s everywhere we go. The ‘anti-architecture’ that I’ve explored in my work has been my way of approaching architecture for its range, and a rejection of the idea that architecture is only sky-scrapers and glass buildings. It’s markets, outdoor churches and everywhere we interact with space of any kind. I want to illustrate the openness and ideas of architecture through the medium of art. The psychology and magic of creating textures, drawings and sculpture form part of my particular architecture.”

As a sculptor, Unathi’s investigation of the three-dimensional became a natural conclusion for his desire to sculpt what he terms more ‘buildings’ than art. I ask Unathi if he is driven by functionality and if in architecture, we can observe an artform that is innately useful – to which he says, “Yes, it’s practical. I’m lucky to be using the word architecture in the work that I do. I use construction materials but in a way that is not functional, and I really respect how architects make things that are functional. In that functionality though, there is a magic that overcomes.”

“I realised that our history is so broad and there isn’t one way to communicate South African history or art,” Unathi reveals, on how his work reflects a continual searching, “with pictures, images, fashion, design and art — it opens up this world where someone could enter these histories in a different way. I think of what I do as illustrating histories in a visual way — beyond what can be read — as an invitation for others to walk into different histories.”

The essence of space and materials lies in their ability to shape the world around us, influencing how we perceive and interact with our environment. Space gives form to our surroundings, defining boundaries and creating relationships between objects, while materials provide the tactile and structural foundation for that space. Together, they form the physical reality we inhabit. Through the thoughtful manipulation of space and materials, we simultaneously construct our environments and the meanings, memories, and narratives that define our lives.

On his particular material concerns that define his spatial practice — which have spanned wooden composite, to fabrics and more — Unathi explains, “I come from a DIY part of the city. I’m self-taught and making things myself, using whatever is around me, became a way to communicate. I started thinking about ideas around sculpture and clothing — like using car parts to understand bodies — or velcro, for example, to fold and bend and illustrate lines. With wood, it’s so solidifying and there’s a level of construction around it that is predetermined and tectonic, so it asks something different of me when I use it. There are certain limitations in the way it performs.”

“The materials I use work from my drawings first and my practice is very strict — there is hardly any mess. I detect the material and push its boundaries and characteristics to see what it can and can’t do,” and “I arrive at a minimalism most of the time in my work. There’s a tidiness and also a punk, DIY sentiment – I’ve had to make my own rules! I come from the club scene — there’s many aspects of me in my work, from Unathi from Peddie, to the city version of me,” Unathi shares, and I think of the likeness in spirit to Rei Kawakubo’s design practice (circa Comme des Garçons). It is precisely the contradictions of blending minimalism and punk that leads to this middleground between the chaotic and the controlled; in which Unathi is stripping back in order to express non-conformity and alternative viewpoints. So often, we tend to think of non-conformity as a deliberate mess — Unathi’s work, similarly to Japanese avant-garde design, is instead a refined yet rebellious exploration of form, challenging conventional aesthetics while maintaining an underlying sense of order.

Photography courtesy of Reservoir

Unathi Mkonto in residence, 2024, Stevenson Gallery Amsterdam, photographed by Jonathan de Waart

While drawing is ever-present and remains a contemplative aspect of his daily life, Unathi’s multidisciplinary eye craved the demand of multiple angles, saying that “drawings are flat. With sculpture, it’s three-dimensional, I have to walk around it – there are five viewpoints. From the back, front, the two sides and the top are all views I have to hold and work with. It has to be ephemeral and I have to see through it; so I have all these different perspectives, even the way the work interacts with the floor is really important. So, it’s a process of negotiation when I’m working with sculpture. I like to look at my sculptures as buildings.”

Something extremely transparent and striking becomes obvious in our conversation; Unathi’s self-assuredness as an artist is totally crystalised. While creative commodification in the modern day often asks us to create in order to be perceived — Unathi is only ever concerned with his relationship to his work, saying that “there’s certain things I like and there’s certain things I don’t like — and my work is always a reflection of me. I do put myself first in some ways and whatever isn’t it, fell away because I wasn’t it. If I prefer minimalism over figurative postmodernism, for example, I won’t respond to it and it won’t occur in the work. I think it’s kept me on my path to know myself and push ‘me’ forward.” I’m intrigued by this natural progression and sense of effortlessness that Unathi embodies, to which he says “Yes, it’s really me – the work is true to that. I’m not trying to layer a cake at work, I prefer simplicity and straightforwardness. It’s not indicative of the area of the world in which I made it, it just is a reflection of me.”

This begs the question, then, for all of us to ask; ‘if I were not the creator of this work, would I indeed actually like it?’ How much more honest could our expression be if we could answer this in perpetuity?

“It’s a lonely process,” Unathi shares on emphasising one’s own viewpoint, “and people are always looking for themselves wherever they go. People enter a gallery space or a show and immediately are panting around the room, looking for something they can identify with! So if everyone is doing this, how could I possibly please them all? The most straightforward thing to do as an artist is to decide to close that door, and put yourself in the work. Not everyone can be satisfied by your work and neither should they be. Making work in order to relate to people as the primary motivation is a bit dangerous!”

What, then, are the ideas currently holding Unathi’s interest? “At the moment, I’m very interested in the way the work is looked at. There’s a lot of art in the world, there’s a lot of sculpture in the world and I happen to be one of those people adding on piles and piles of work. I’m thinking a lot about this. I would like my work to be viewed as buildings rather than sculptures; I might arrive at art, but it doesn’t begin as art,” and that roadmaps and blueprints for a distinctly South African expression means that, “creating languages is really exciting for me. Creating languages for the continent — specifically design languages. It’s time for us South Africans to build our archives and we are making works to create languages, not necessarily to entertain.”

It would be remiss to not touch on Unathi’s relationship to fashion and he offers this up in lieu of his latest hobby, but first — I must contextualise his effortless chicness back into the fold of his multidisciplinarism; “I went to LISOF for a year and I was really good at it, but I was advised by my fashion lecturers that the designs I was making would struggle in a South African market — people were not there yet. I asked myself whether I wanted to take the long route of educating, or do I want to do something else? The clothes I wanted to make would probably sit better in art galleries. Now, there’s an explosion of fashion in South Africa of amazing designers leading that charge.”

It’s with this background that Unathi’s latest hobby is impossibly cool, “I’m building my summer wardrobe, my hobby at the moment is making clothes. I’m starting to make some pieces I developed last summer and I just really enjoy the process of making things,” Unathi notes, “I work with an incredible tailor and it’s now become a very serious thing – from sourcing fabrics, to being very involved with my tailor to understanding my body, what falls best and is cut well. I’ve learned so much from actually being involved in the process of making clothes, there’s such a liberation in going behind the scenes.” Unathi’s deep personalisation of each thing he loves, and the intention with which he does everything, is a remarkable energy to witness.

Lastly, Unathi extends a vulnerable reflection — that art was never his first priority — “I resisted making art for a long time so I think that’s why I went for architecture and fashion first. I thought art school would be too playful and not serious enough! But all the work I made ended up being better suited to galleries, so I had to relent to making art.” Now, “Everyday I wake up, anything could happen. It’s exciting.”

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za