Dada Khanyisa has integrated their workshop and home space into one. For them, there are few boundaries required; as a ‘maker of things’ for whom making is truly, and earnestly, their life’s greatest pleasure. Tucked away, out of view, on a busy street in Woodstock—Dada’s home is a sanctuary, with a direct view to the external, chaotic world that so informs their thematic focus. Social scenes, human interactions, rituals of everyday life and cityscape mythologies; Dada has situated themselves where they feel most comfortable. With a slight distance, and privacy, and proximity to the pulse of the city, they maintain both observation and immersion.

Dada’s home is a feat of their ingenuity and self-initiated fate as a tinkerer of anything and everything—“I was six when I started apprenticing with my older cousins. They were always working with their hands—woodwork, tools, fixing things. I was assigned the task of sorting the nails and handing over tools. Through that I learnt how to use hammers, pinchers and a leather sewing awl” they tell me. “They never doubted I could do it, and because of that, I never doubted myself either.”

Dada’s pathway as an artist is the result of many things: raw talent, a hunger for experimentation, and a deep respect for process—but perhaps most significantly, they are a testament to what being raised to nurture one’s creativity can do. For Dada, there was only the possibility of how far they wanted to go. “My grandmother would show me off at family gatherings—she’d hand me a piece of paper and a pencil and ask me to sketch someone on the spot,” Dada muses, “that kind of encouragement made it feel natural to pick up a hammer, to paint, to build. No one was surprised when I pursued this path.”

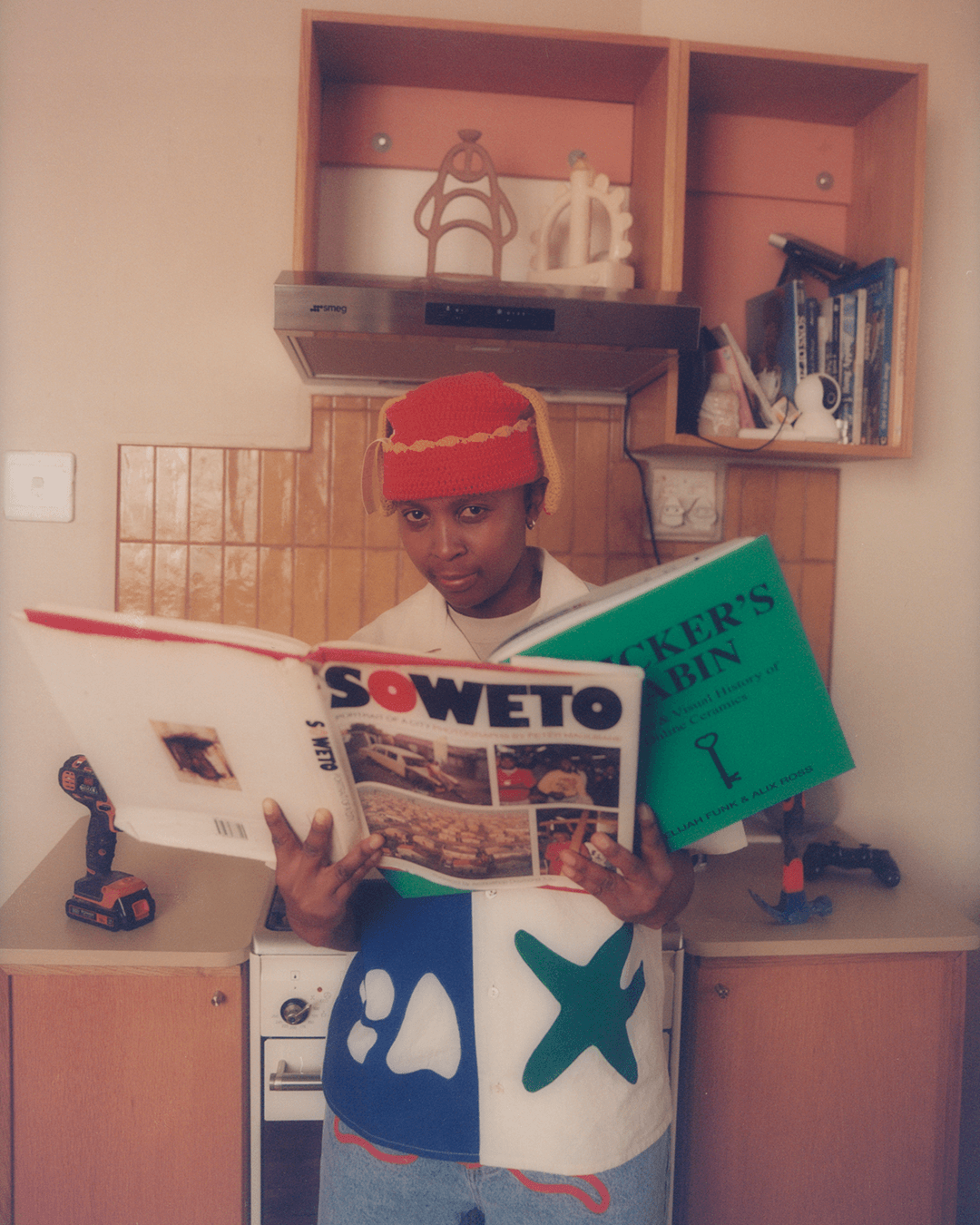

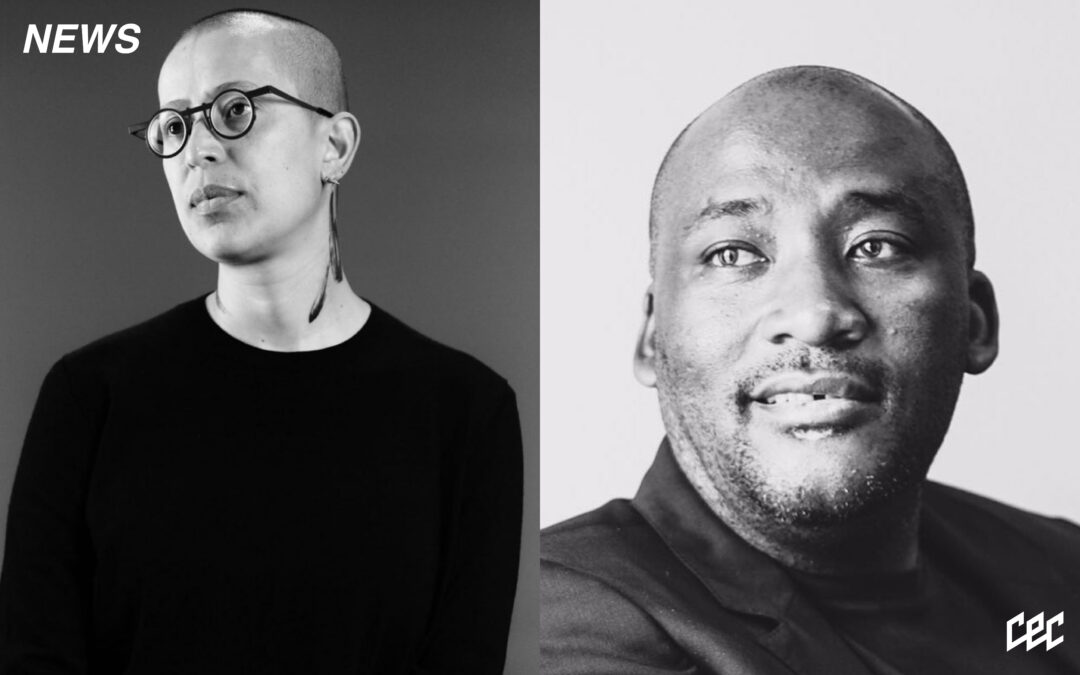

Dada Khanyisa, Photographed by Cris Fragkou, Produced for and by CEC

Dada’s space is both living and working. Their kitchen—and almost all their furniture—was forged in the workshop just off the living room. They had tasked themselves with the carpentry of the kitchen units and the TV console I’d mistaken for a rare mid-century find. The space is imbued with the colours of Dada’s world: mustard, ochre, hints of green and brown—a rich, autumnal palette that tempers so much of their work and, clearly, reflects their personal taste. As Dada tells me, they were pleased when they tackled the kitchen cupboards— and realised they could actually make almost anything they wanted. This is a rare kind of power and skill in a world that demands our allegiance to consumption, and outsourcing all of our desires and needs.

Dada’s artistic practice is multi-disciplinary in the truest sense of the word. Their works can, quite literally, involve numerous processes and skill sets—layering technique and materials to build the sculpture-meets-painting-meets-installation that has become their signature. Each piece is a convergence of elements: carved wood, hand-painted surfaces, and found objects, often unified within a single composition. There’s a tactile complexity to their work—one that invites the viewer to consider the labour, intuition, and experimentation embedded in its making. It’s a practice that feels alive, ever-evolving, and deeply personal. “I tried to do the ‘practical’ thing and study animation,” Dada notes on their formative years, “the narrative was that there was no money in art. Animation gave me something valuable—it helped me form a visual language. As part of the animation programme, we did storyboarding and that taught me how to pose figures, how to communicate through the body.”

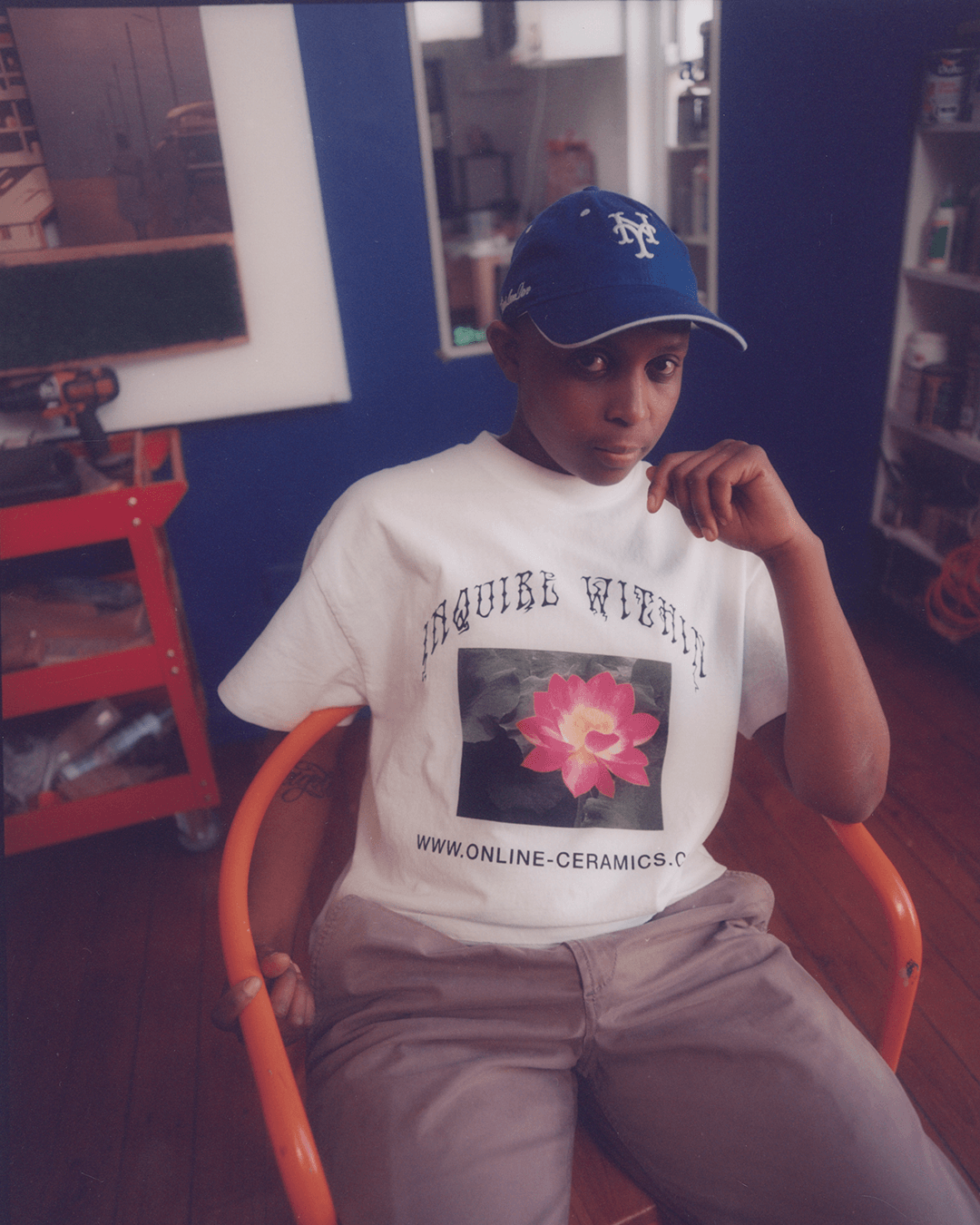

Dada Khanyisa, Photographed by Cris Fragkou, Produced for and by CEC

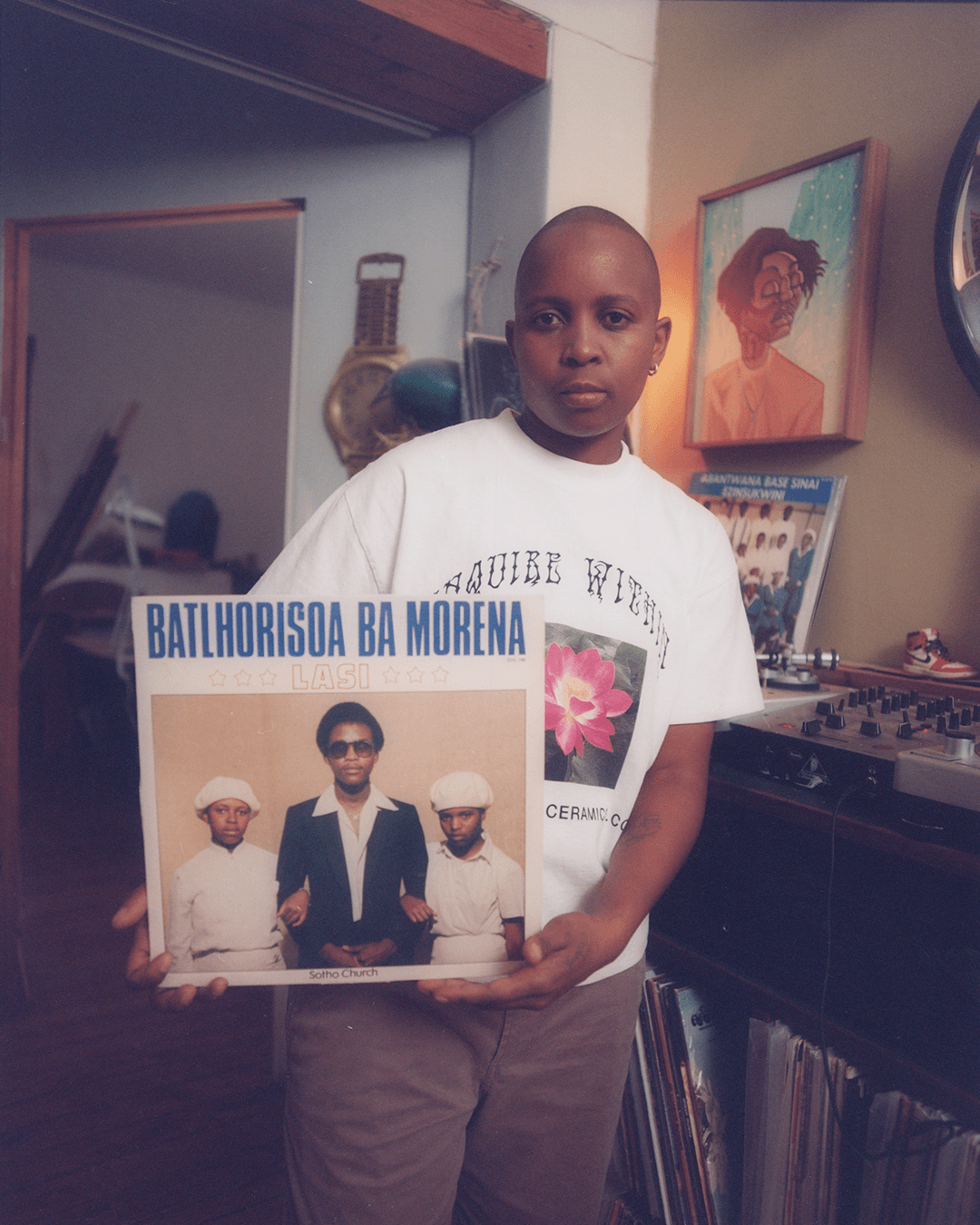

Dada Khanyisa, Photographed by Cris Fragkou, Produced for and by CEC

Surprisingly, Dada’s understanding of the so-called ‘efficiency’ of digital art was completely subverted, leading them to find their practice as it stands today. “At Michaelis, we had an elective that involved digital fabrication—CNC routers, laser cutters. Because I could model in 3D, I leaned into that. I sculpted a figure digitally, but the process was so long—over six hours of modelling and rendering time. Then I tried carving it by hand and finished in 30 minutes. That changed everything.”

“We’re told digital is quicker, more efficient—but that experience flipped the script,” they explain. “I realised that working with my hands is more true to how I want to create.”

Candice, CEC’s editor in chief and founder, points out that when shooting this cover with photographer Cris Fragkou, Dada’s sculpting of wood was like witnessing a choreographed meditation; so mesmerising and focused. It is a hard-earned process, harkening back to Dada’s earliest memories as an apprentice to her cousins, and that “In art school, there was a lot of direct referencing, I think it’s because we were all studying the same artists, the same techniques. It was important for me to establish a visual language, I didn’t want to replicate anyone. I wanted to push it so far that copying me would be pointless. You’d have to just go and make your own thing.”

Dada’s style is instantly recognisable—playful yet poignant, grounded in lived experience yet elevated through formal experimentation. Their use of 3D forms has become a way to collapse boundaries between painting, sculpture, and design, and their portraiture of figures emerge in low relief, sometimes fully sculpted, often embedded into flat surfaces or architectural structures. These forms, of snapshots into Dada’s mind and memory as they observe South African youth culture, feel tactile and bodily, inviting attention and emotional proximity. You are with the work itself, rather than viewing into a flat painting or scene, and this dimensionality gives their work a visceral presence—one that anchors narrative and form in the same physical space. Of this, “I arrived at this very three-dimensional, layered way of working,” Dada explains. “It was selfish in a way—I didn’t want anyone to easily do what I do. My use of materials, my technical processes, even my visual language is designed to stretch beyond imitation.”

Dada thinks of themselves first and foremost as a maker of things—but also, more quietly, as a student of human patterns. Their work is deeply observational, a way of mapping energy in urban spaces, tracking how people connect, and uncovering what drives them. “I believe you have to live in order to make meaningful work,” they tell me. “I go out, I experience, I overlive—and then I retreat and make work to process it. Sometimes the work is healing. Sometimes I’m wounded when I start.”

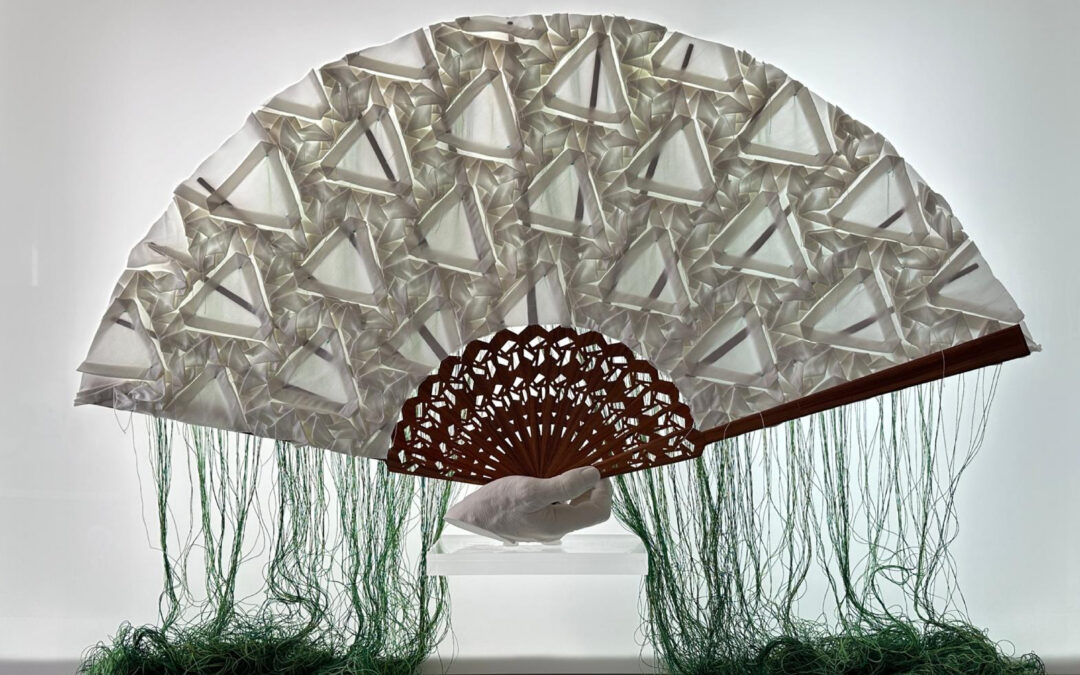

Dada Khanyisa, Photographed by Cris Fragkou, Produced for and by CEC

For Dada, making is a survival mechanism. “There’s a link between my spirals and my productivity. When I’m spiralling, it means I’m not working. But when I’m not working, I start to spiral. So my practice keeps me tethered. It’s how I stay grounded.” They reflect that their need to be in motion is constant—“I think I’m one of those people—maybe it’s ADHD—who has to be doing something. I can’t really go on vacation. Sitting still doesn’t work for me. I become a better person when I’m working with my hands.”

This rhythm—of outward immersion and inward reflection—runs through all of Dada’s work. “My practice is rooted in documentation,” they explain. “Observing, noticing, absorbing youth culture, people, environments. It’s not always about direct portraiture.” Instead, their pieces function like condensed social encounters—layered, vivid, and vibrational, offering glimpses of life as it’s lived and felt, “sometimes it’s just a visual that sticks with me. Sometimes it’s a moment that unsettles me.”

Most recently, Dada has found their work becoming a vessel to process and reconcile with history. While they never set out to be overtly political, they’ve come to feel that, “being a Black artist in South Africa, I think your work is inherently political”—and embracing this has opened up new thematic terrain. One such thread began with a photograph pulled from apartheid-era archives, showing a moment during the prohibition of alcohol for Black South Africans. “I learned about the prohibition of alcohol to the natives,” Dada explains. “There was a prohibition in the 1950s, and people were brewing their own alcohol, which created this huge demand. So when the ban was lifted, people got drunk for seven years.” They describe the period as one of calculated chaos, “it was a way to disarm people, by restricting alcohol and then lifting the restriction.”

Dada draws a parallel between this and contemporary marketing strategies, pointing to the ways major corporations like SAB used cultural influencers, even back then. “They were working with Alf Kumalo, a photographer for Drum, and they’d use these figures to promote alcohol—just like today’s influencers.” This historical thread, rooted in control and trauma, became a lens through which Dada began to view their own fascination with club culture. “Growing up in Joburg, it’s like we’re groomed to spend time outside drinking,” they reflect. “I only really became aware of it when I moved to Cape Town—it’s slightly different here.”

Alcohol, in their eyes, is both social currency and a survival mechanism. “It was a lubricant for the conversations they were having—a meeting point—and a medicine for trauma.” They point to the 2020 alcohol ban during lockdown, where domestic violence and trauma-related hospital admissions dropped significantly. “The direct link was quite distinct,” they say. And yet, despite the glaring public health consequences, accountability is elusive. “I’m so curious why SAB hasn’t been held accountable. Tobacco companies fund research into lung cancer—but SAB? Nothing.” They note how SAB quietly relocated their head office to London after lobbying to change a four-year restriction. “If we wanted to protest, we wouldn’t even know where to go anymore.”

Still, Dada insists this isn’t a crusade. “I’m not saying alcohol is bad—I’m just questioning the relationship we have with it as a nation.” It’s this tension—between historical harm and cultural ritual—that Dada continues to unpack through their work, holding space for discomfort and curious reflection.

Part of what makes Dada’s practice so magnetic is their refusal to be boxed in—by medium, expectation, or market logic. “Part of my fate, I think, is to tell stories—my own, and those of others,” they explain. “That’s why I don’t confine myself to a single medium. My style is the throughline. The hands, the stories—they’re what drive the work.”

Dada Khanyisa, Photographed by Cris Fragkou, Produced for and by CEC

Their hands are deeply intentional, pushing against the sleekness of mass production, imbued with their own intelligence that Dada often surrenders to. Dada lights up describing their obsession with handmade objects and ‘third-world’ ingenuity: “I was going through my timeline and I’m noticing that people are drawn to handmade items or objects from supposed third world countries. I was obsessed with those—the teapots, the people who build houses with bamboo sticks. Building pools. A whole setup on a time loop.”

For Dada, making by hand is a kind of affirmation—a way to stay human in an accelerating world. “It’s such a fulfilling process to actually do it by hand. I’ve had to remind myself that I’m a person—I’m not chasing a machine finish. There must be something that reminds you that, oh, this is handmade. There’s a mistake or it’s what the hand intends.”

Dada is grown-up now. Signed to a gallery in London and incredibly accomplished, they reflect on the visibility of their journey, aware that they’ve grown in front of an audience; “It’s interesting now because I feel like I was a child star. My career is unfolding in real time, in full view. People have seen me from my early days as an animation student. I used to make these small miniature shoes because I was obsessed with sneakers.”

Back then, they weren’t out to change the world—they were simply making. “I hadn’t studied a BA so I didn’t have the ‘change the world’ approach. I could make things, ‘let me just make this!’” This spirit, of simply making, is continual, yet, “It feels like I’m an adult now. I feel established. Now I understand my language. Sometimes it’s just muscle memory—I can zone out and my body will make and carve. My hands definitely have their own intelligence. It’s like when you’re driving and you can zone out—you don’t think about it. You just drive.”

This confidence shows up in how they speak about decision-making. “Now it’s easier to trust my decisions. I just say, ‘This is what I’m working on.’ I do not motivate for it.” It’s a far cry from the early days, “when I started my BA, I decided I would never put my destiny in someone else’s hands. I have to be certain about my ideas and present them from a place of certainty—not asking, ‘Is this okay?’”

While many artists expand into teams or studios, Dada is clear that their solitary process is central to their integrity. “For me, the whole thing is personal. That’s why I don’t work with people—not from a place of hoarding skills. I’m an only child. That was an escape for me—being in my room, drawing, on the computer. There was no one else interfering.” That childhood solitude has become their adulthood respite in this world, as Dada notes that “you embody all the skills you need. Some artists need assistance or technical hands to execute an idea, but I’m in a unique position where I can do it all.”

Dada smiles, “I think I’ll always be the sole artist creating my works, because if not, I’ll be a very horrible person!” Their deeply personal, fiercely independent approach is exactly what gives their work its power. Within each carved surface and layered form, Dada invites us into a world that is entirely theirs, and Dada’s process reminds us that creativity is, in truth, about knowing precisely who one is at their core; and respecting this every step of the way.

I leave Dada’s home looking down at my own hands, questioning whether I’ve allowed them the space to actually make — this, I think, is what Dada’s work really teaches; alongside observation and the art of playfulness.

Creative Credits

Photographed by Cris Fragkou

Produced for and by CEC

Editor in Chief: Candice Erasmus

MUA: Xola Makoba

First assist: Alex Birns

Production assistant: Grace Crooks

Written by Holly Beaton