In an Afrofuturist context, one of things I find most fascinating is its ability to take the linearity of time – in the western sense – of past, present and future; and rather expresses ‘time’ as this intersecting, co-current phenomenon, in which everything is always being made a-new. Manyaku Mashilo is an artist (though not specifically of the Afrofuturist school) whose work embodies this with incredible precision. Manyaku’s work is an examination of self and relationality; embedded with the cognisance and celebration of her ancestral lineage. Her visual expression consistently arrives at the conclusion that ‘herself’ is inseparable as an entity from those who came before her and those who will exist after her.

Manyaku is an embodiment of time passed, present time and time still to come; manifesting in the material space, as a potential of all these presences. As Manyaku states in our conversation; “I am trying to find a visual language that can share this feeling I have of the hybridity that lives inside of me and between the complicated histories that I have – the ancestral and contemporary, the future and the present.”

For her recent solo-exhibition at Southern Guild, Manyaku showcased ‘An Order of Being’; which dealt exclusively with her internal experience of hybridization, as a collection of her reckonings with the richness of tradition – of indigeneity and religion, myth and meaning, time and space – and ultimately, the future. Incomprehensibly powerful figures adorned in red, depict Black women – of Manyaku’s memory and myth’ – as beings iterative of the future. Using technique and colour, this show stands as Manyaku’s most self-defining body of work yet; incredibly layered and deeply thoughtful.

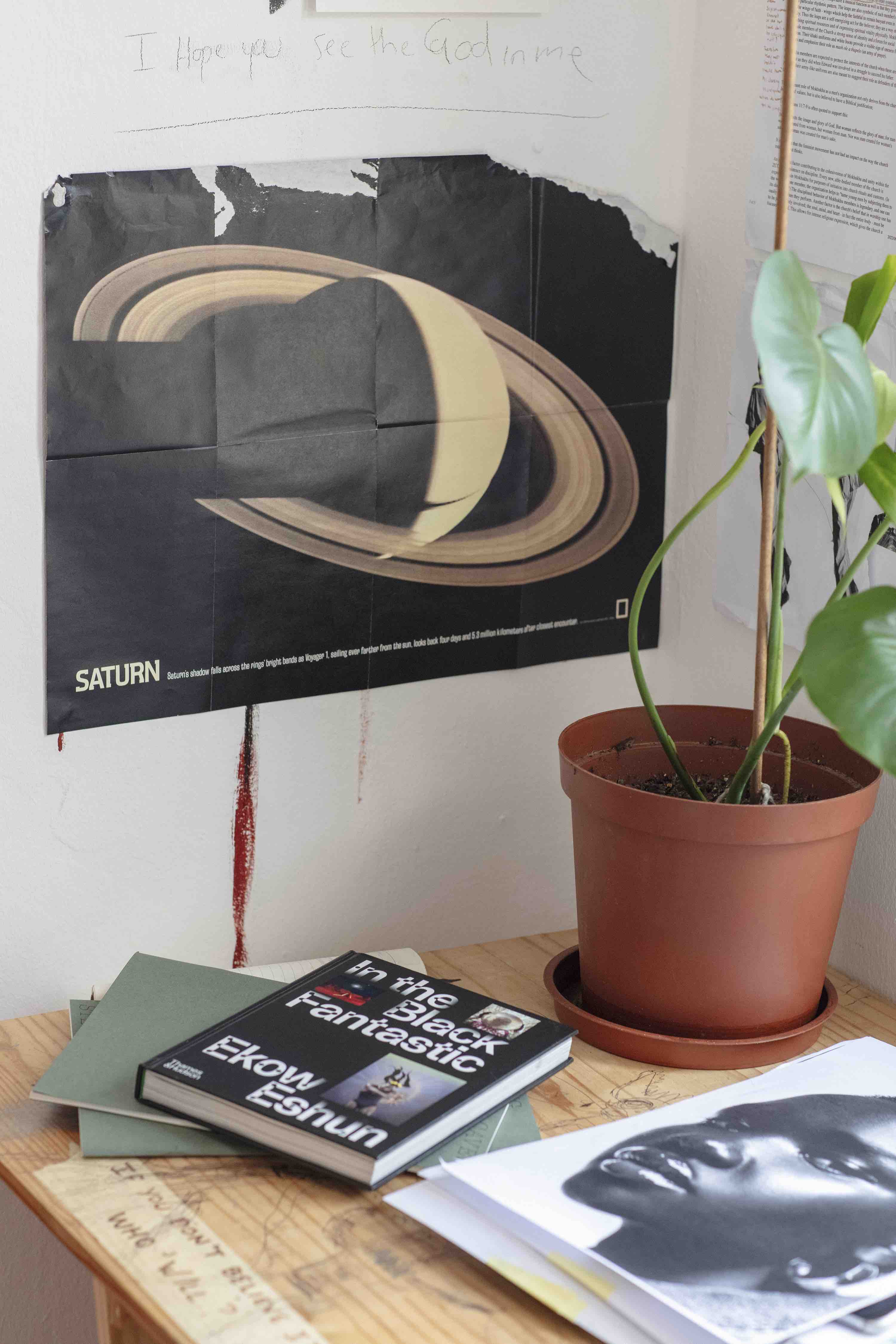

Manyaku Mashilo Process, 2023, photographed by Hayden Phipps and Southern Guild

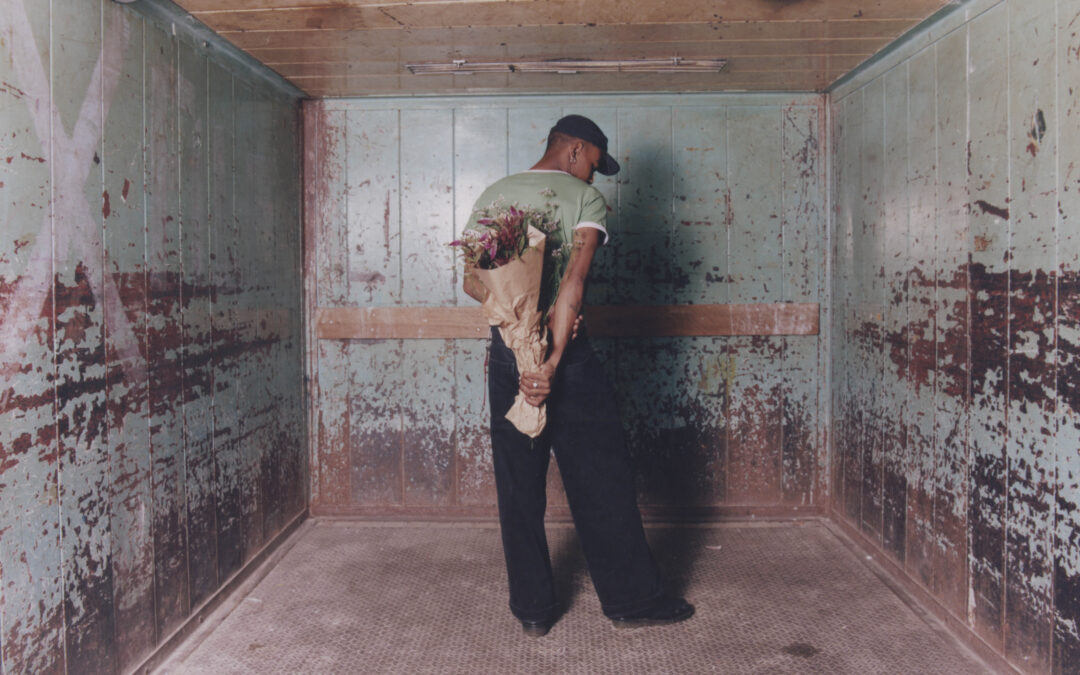

Manyaku Mashilo, 2023, photographed by Hayden Phipps and Southern Guild

Manyaku Mashilo Process, 2023, photographed by Hayden Phipps and Southern Guild

In our conversation, I ask Manyaku where her work as an artist originates, to which she explains that, “my background is in fashion design. My siblings and I all wanted to be artists, but our dad was always trying to push us towards creative pathways that were less risky. A lot of the women in my family are seamstresses – so the world of textile and clothing came very naturally. At fashion school, we had subjects like art history and fashion illustration; and these drew me in. The fashion world wasn’t very inclusive at that time and I wanted to find a place in an industry where I could be uncompromising myself.” It was the subject of art history that first initiated Manyaku’s curiosity for mean-making as the direction of her pull toward creative expression, saying that “art history taught me an understanding of form and how I could build this world of my own, through the lens of critical and cultural theory, but as a creative expression. I dropped out and then worked at a gallery. The gallery was my university – it was an incredible education, especially artist liaison, and I learned from them how to explore mediums.”

For Manyaku, revisiting historical and ancestral narratives through her contemporary experience, was a solution to the lack of representation that has sought to repress and oppress Black people, specifically in the context of creative disciplines. As she says, “I started with sketching and I was initially interested in portraiture. I hadn’t seen myself or my friends reflected much in either art or fashion. So, my creative beginning starts at a place where I didn’t see myself – and so I had to purge and reckon with that.”

Manyaku’s work is cosmic-building, and she has referred to her work as an ‘act of cherishing lineage’ – I ask Manyaku, how in the process of examining herself and identity, it has led to expand across space and time to include her lineage – physically, ancestrally and as a lineage of ideas and preservations? To which she says, “I just knew that in whatever I did, I could not speak of myself without referring to my grandparents and the knowledge that they have passed onto me. While I was putting together my solo exhibition, I had this recurring memory playing in my head. I’m from Limpopo and my family is Christian, but the church we are a part of, practice through traditional means,” and that “our indigenous knowledge systems are involved in our interpretation of Christianity. There is this duality involved in my lived experience – and the memory I have is of these three framed images on my grandmother’s wall. One of my great-grandfather’s portraits, then of her and her husband in their church uniform, and then in between them was a knock-off of The Last Supper. I realised these images are the perfect juxtaposition of what my life is like; it is a blend of acknowledging my ancestors and their way of being.”

When Manyaku’s grandfather passed away, the last original hut that he was raised in burnt down. From the ashes, the only thing that survived was a tin of her great-grandfather’s herbal medicines, and Manyaku reflects that “there is always this presence of ancestry of lineage. The way that I understand myself and the way that I move forward is understanding that they are always with me. We believe that you have to look into the past, to look into the future. It is very important to me that my work reflects my contemporary presence and reality, alongside the presence of ancestry.” Beyond all material epitaphs left behind by her ancestors; it was the herbal medicine that survived the fire. I am sure a more literal metaphor for the sanctity of indigenous knowledge and the work of honouring it, could be offered; such is the wisdom of Spirit.

In an ‘Order of Being’, Manyaku’s figurations are Black women, exalted in what reads as a cosmic, liminal space; suspended over forms (mountains, among the stars?) – and one of the distinctive features of Manyaku’s mixed-media approach was the incorporation of red ochre; woven throughout the works, most evident in the skin tone of the figures. On why ochre, Manyaku notes that “I am really interested in the use of ochre; the way women put it on their face. It reminds me of my old pictures of my grandmother in the fields with her friends, with ochre on their face, or how they used ochre to seal the house. They way they used the natural things around them in this multipurpose way in daily life. My connection to it is very different, to even source this ochre was ridiculous! I didn’t want to harvest some from Limpopo and bring it here. Rather, I had a small jar that I needed to use very sparingly which I applied with my paint, especially for the faces. It created a brand new skintone that revealed itself throughout the process. The graininess and texture, the colour that it brought – it became integral to the body of the work.”

In the urbanised and globalised world of today, many are required to leave their home in search of their purpose. Somehow, this is a modern rite of passage; which Manyaku acknowledged in through the use of elemental ochre as an imprint of the land, “moving to Cape Town showed me how important land and belonging was to me. I grew up on my grandmother’s land that she owned – which not everyone has the privilege of experiencing. I haven’t been to Limpopo in a while and the longer I live in Cape Town, the more I have the sense that ‘this isn’t home’. It’s more that – okay, you’re here for work – this is temporary. Being a contemporary means that we sometimes have to be dislocated in that way, from our family’s land or home. So, using the ochre was part of acknowledging this.”

The oxidised, mineral rich composition of ochre is one of the most striking features of the planet’s array of pigments. It is often cited that ochre is one of the first – if not the first – paint to be used, by our earliest ancestors, thousands of years ago. Ochre’s presence within indigenous knowledge systems is ancient and enduring – as Manyaku reflects, “ochre is used in a lot of rites of passages. When girls go through the initiation process, to come back into the world as a woman. We go to the mountain as a young girl and undergo different experiences – from speaking to elders and other tasks – and throughout that whole process of transition, we have to wear this red ochre the whole time. I like the idea of this armour that we put on to protect us and to signift to people that we are in this transitional space. It communicates to other people to not approach because of the spiritual sensitivity.” Manyaku’s focus on her indigenous lineage is central to her artistic practice; and it cuts many forms, “I love the intentionality behind the understanding that we re-emerge as new beings and that we have these customs to facilitate and protect us throughout this, [they] are so thoughtful and specific. The colour red has become a key part of my work, and it symbolises the generosity of the knowledge systems that we as African descendants on the continent hold.”

Manyaku Mashilo ‘Being Black’ & ‘How about a New way to Pray’, 2023, photographed by Hayden Phipps and Southern Guild

Manyaku Mashilo ‘An Order of Being’ 2023, photographed by Hayden Phipps and Southern Guild

What has Manyaku’s show beckoned her with, that she wishes to share with others? Manyaku notes that “we need to understand that we are the land. We are part of the ecosystem and we need to treat it in a very sacred way. There is this relationship with the land, body, self belonging and knowledge systems that I think I will always explore in different ways. A lot of my work is spontaneous but I do feel these are threads that I will keep following, with the guidance that I am given.”

The futuristic imaginings of Manyaku’s works are an invitation to viewers to interpret their own ideas of progressing and moving forward. As an artist, her work stands beyond this world – though it draws on all Mankyaku has come to understand about life. The rich tapestry of lineage and culture will keep Manyaku nourished; it does for us. As she says, “I want people to be able to imagine what the place beyond now looks like. What does it mean for you to arrive? I want my work to ask people that question, of the future. You know, maybe we do arrive? Right now, the journey of the self is endless.”

Written by: Holly Beaton