Overtime, these insights evolved into deliberate, scaled practices – finally taking flight as a massive component of the emerging agricultural civilizations. One of the earliest known examples of such organised societies in Africa is the ancient Kingdom of Aksum, situated in present-day Ethiopia and Eritrea. The region’s climate and soil suited cotton cultivation, with fibres skillfully processed and woven traditionally into textiles. Aksum’s cotton textiles found use locally and were traded through ancient networks, bolstering the economy. When I was considering this month’s Interlude, this topic felt like a return to the most simple – yet important – facet of fashion. Our fashion column has served to highlight many brands and concepts, but we haven’t singularly focused on the realm of textiles and fabrications. It is certainly a mammoth topic and not a subject easily distilled into an article; which in itself suggests the intense importance of returning to materiality as we conceive of and celebrate the world of fashion.

Within our burgeoning South African design landscape, the history of textile production in South Africa is a complicated interplay of indigenous practices, colonial influences, and modern dynamics. Before European colonisation, indigenous groups such as the Khoi and San peoples wove textiles using natural resources like grass, reeds, and animal hides. These creations served multifaceted roles such as adorning clothing, constructing shelters and embodied cultural significance.

Similarly, Nguni communities (isiZulu, isiXhosa, Swazi and Ndebele people) in pre-colonial Southern Africa showcased textile craftsmanship through diverse techniques. They practised (and continue to do so) weaving using plant fibres such as grass, reeds, and palm leaves that are then collected, dried, and skillfully prepared to form robust and flexible materials. Employing backstrap looms or frames, these are woven, producing textiles employed for clothing, blankets, and mats. Beyond functionality, weaving holds profound cultural significance, with designs intricately woven into fabrics conveying personal identity, lineage, and social standing. Leather and animal hides are equally integral. Nguni people prepared these materials through tanning, smoking, and softening, transforming them into clothing, bags, and accessories. These textile practices are interwoven into Nguni societies, reflecting their profound connection to the land, cultural identity, and social structure.

In the colonial era, Dutch and British colonists introduced European weaving techniques to Southern Africa, blending them with local materials like cotton and wool. This fusion gave rise to cottage industries in the 17th and 18th centuries. The 19th century saw cotton cultivation gain momentum, leading to small cotton mills. The 20th century marked significant technological advances and urbanisation around the world. driving textile mill expansion and employment growth in cotton and wool production. However, apartheid and colonialism have disproportionately impacted Black, Coloured and Indian South Africans’ participation in the industry; these effects, of colonialism and apartheid, are still felt today. This is why the textile ecosystem in South Africa remains a politically and culturally significant area of developing a fashion industry and design future that hinges on equity and sustainability.

Perennially at the forefront of sustainability, Twyg is a publication and NPO that have long been considering and activating new and ancient understandings of where we could head as a country, continent and world across fashion and design. In August, they hosted the third edition of ‘Africa Textile Talks’ together with Imiloa Collective. Under the guidance of MC Thobile Chittenden, the day was filled with insightful talks, presentations, exhibits between sustainable growers, makers, designers, creatives, industry experts, retailers, and innovators.

Twyg’s assistant editor and sustainability honey of note, Stella Hertantyo, shares that ATT is less focused on technology as we understand it from an industrial perspective, rather “we need to reframe our understanding of “innovation”. When we think about innovation, and the future of fashion, often high-tech solutions come to mind. Instead of relying on endless technological innovation to solve the world’s most pressing problems, we need to reckon with the systems that underpin these systemic issues. And listening to the speakers was a reminder that low-technology solutions are essential for shifting the culture of overproduction and overconsumption. Low-technology solutions prioritise simplicity and durability, local manufacture, as well as traditional or ancient techniques. This often involves looking to practices from the past for inspiration. For example, regenerative farming is a key example of a low-technology approach – mohair designer Frances van Hassalt and knitwear designer, Natalie Green (or Inke Knitwear) spoke to this.” Touching on the ‘geographically siloed’ way in which Africa is understood, Stella goes onto describe the importance of ensuring that a Southern African perspective of textiles encompasses the richness of the entire continent, and vice versa, “To forge a future where textiles can be the foundation of positive social change, we need to break down the imaginary barriers between African countries and form meaningful collaborations. The resounding feeling in the room was that this was the first time in memorable history that people from across the continent had gathered to understand the shared experiences and unique challenges of textile creation on the continent. And that breaking out of these geographic silos was essential for moving toward the future that we all imagine.”

Stella points out that “it feels as though we are in a time where our fashion and textile systems need a new blueprint. And the textile ecosystems across the continent offer exactly that. Understanding the textile landscapes of the continent uncovers stories that have been left out of history books and narratives – including that sustainable textiles are not new, they have always been present on the continent.” For the work that Twyg does, with their vast network of some of the most critical voices in African fashion, their stance on a holistic focus for South African textile futures hinges on the slow fashion ethos; a way of creating and proliferating that is intrinsic to Africa, “ethically, sustainably, and thoughtfully created textiles and fashion have the potential to catalyse positive social change when it comes to job creation, sustainable livelihoods, archival work, and knowledge production. Of course, we live in a world where we need to produce less, but the African blueprint is slow fashion in nature. So cultivating thriving textile economies in countries across the continent is also a way of pushing for holistic and inclusive economic transformation.”

Designers Exemplifying Textile Craftsmanship

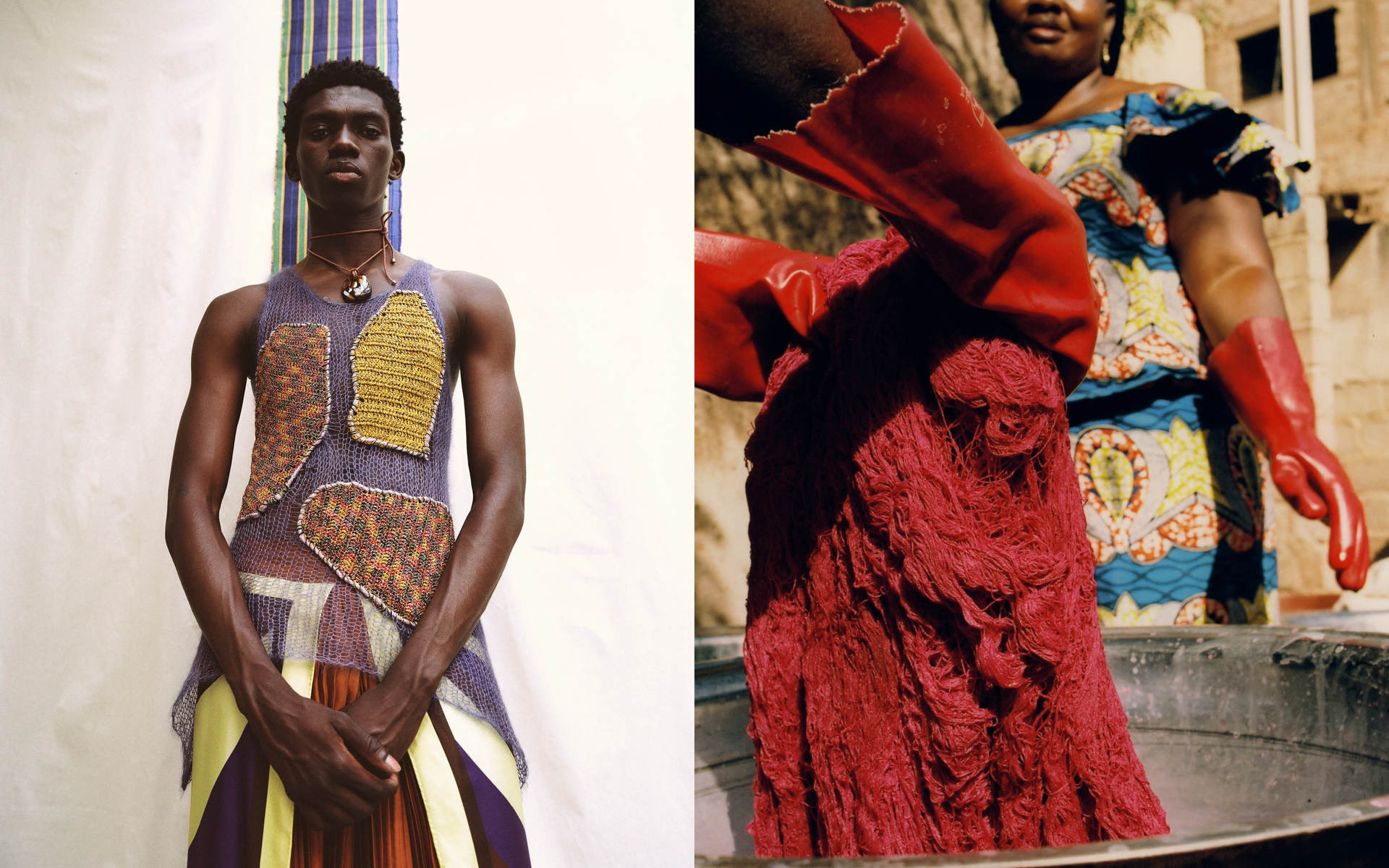

Lukhanyo Mdingi’s eponymous label needs little introduction. Since the label’s inception in 2015, Lukhanyo and his team have always maintained a strong focus on the use of natural fibres. From their merino and mohair wool, originating in the Eastern Cape, and their relationship with textile communities in Burkina Faso; the Lukhanyo Mdingi label is invested deeply in understanding natural fibres through the lens of ‘the hands that make’. As Lukhanyo says, “it feels very real and honest to use the breadth of textiles that exist in South Africa and the continent. Our merino wool, our mohair, silks and cottons hold a greater story behind them – which are the communities of artisans and textile artisans that we work with. I think we are able to reflect, and in some way assist in preserving, these really critical lineages of textile craftsmanship through our label and show people the contemporary possibilities when using these materials.” Even in luxury fashion, though, it is difficult to achieve a fully-natural fibre orientation. Lukhanyo explains that “we aren’t completely confined to natural fibres, but they form the heart of what we do and how we consider each collection. It’s very important for us to retain the integrity of using natural fibres as much as possible.”

Lauded as one of most versatile, durable and widely used textiles – cotton remains a massive aspect of South Africa’s textile industry. Cotton has been deemed unsustainable due to its intensive use of water and pesticides, as conventional cotton farming accounts for a significant portion of global pesticide and insecticide use, causing harm to ecosystems and human health – alongside major social inequities across the supply chain. This is true for all fabrics, but that’s a story for another day.

To remedy this, CottonSA is a South African non-profit organisation that was founded to promote sustainability and responsible practices within the cotton industry. It serves as a platform that brings together stakeholders from various sectors of the cotton value chain, including farmers, ginners, merchants, and textile manufacturers. CottonSA’s main objectives include advocating for sustainable cotton production, fostering collaboration among industry players, and advancing social and environmental standards within the South African cotton sector. CottonSA is affiliated with the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI), an international organisation that aims to make global cotton production more sustainable.

The Better Cotton Initiative works to improve the social, economic, and environmental aspects of cotton farming by providing training, resources, and support to cotton farmers. BCI promotes the adoption of best practices in cotton cultivation, including reduced pesticide use, water conservation, and improved labour conditions. It also encourages farmers to adopt more sustainable farming methods that benefit both the environment and the livelihoods of cotton-producing communities. I highly recommend exploring CottonSA’s website, which provides scrupulous information, market analyses, cotton classification and practices.

Lastly, it would be remiss to leave out the beautiful bounty from our bovidae friends. Wool from goats and sheep are biodegradable and renewable and South Africa boasts a proud heritage in producing these animal fibres for textiles. Mohair, a luxurious natural fibre renowned for its sheen and durability, plays a pivotal role in South Africa’s textile economy, emerging from the Karoo region. Mohair South Africa oversees its production, fostering sustainable practices among Angora goat farmers. Karoo’s semi-arid climate provides optimal conditions for these goats, yielding high-quality mohair with unique lustre and softness.

Similarly wool primarily sourced from merino sheep, is a cornerstone of South Africa’s textile sector. Renowned for its fine quality, merino wool thrives in the country’s diverse landscapes. This industry bolsters rural economies, emphasising ethical and eco-conscious practices. With Cape Wool as a key organisation, South Africa’s wool sector continues to pay homage to our rich agricultural and manufacturing heritage.