We have never lived under more commercialised conditions. Contrasted against the pursuit by so many to forge creative paths that can actualise as fruitful careers – we still find that one of the strongest components for developing ones work in the world is the necessity of financial, sustained security. So, the notion of being a ‘conceptual designer’ in the fashion industry is a rare mantle to take up. To push the boundaries of traditional fashion design through storytelling, symbolism, and experimentation into their creations and to challenge conventional notions of style and beauty is a kind of privilege that many designers have to contend with. This is done amid lack of resources, infrastructure and the ever-gleaming road of corporate safety. It takes a young designer like Yamkela Mahlelehlele to lay down a kind of framework that the two need not be mutually exclusive; Yamkela is a recent graduate of CPUT’s stellar Fashion Design department and is a ‘conceptual designer’ – and yet, she has found that working for and alongside commercial brands has only strengthened her point of view as a conceptual designer. You might have seen Yamkela at events dressed in experimental pieces; if not in real life, her Instagram serves as an archive of her work as a DIY, upcycling virtuoso.

In our conversation, Yamkela describes the focus underpinning her work, “I refer myself to a fashion curator, as well as a designer. I say this because I’m concerned with immersing myself in as many different aspects of the industry that I can – my skill set is in design and construction, but I think fashion is the primarily the way that I’m telling my story and finding my community. My main objective is to create things that are both relatable but can be understood as art.” I am endlessly fascinated by upcycling as a response to both our consumption problem in fashion, but also as a means to reimagine the old. I ask Yamkela how, in and among learning to create new garments from scratch throughout her studies, upcycling became her primary vantage point? To which she says, “it started from being broke, to be honest. I ventured into thrifting and I started to find amazing pieces for cheap. From a young age, I liked the idea of turning something from its original into something different. Giving things a second chance and being in the fashion industry, I understand how much we contribute to the destruction of the planet. Through my work, I try to find ways to make something new of things that have been discarded. I feel like it’s a way of working that is a metaphor for the human experience; giving people second chances or being seen is so important, and I want to apply that idea to fashion.”

Not only is differentiation through upcycling an ethically valuable mode of designing and not only is it brilliantly creative for Yamkela’s self-expression; differentiation is the absolute key for designers against a saturated market and fosters a competitive edge. Though for Yamkela it’s not about competition, for her it’s rather about community – a designer like Yamkela showcases what it means to expand the idea of innovation. Rather than continually seeking newness, she seeks expansion from forgotten materiality through the lens of newness itself. As Yamkela explains, “I like to deal with one-off pieces. I know this is difficult to scale, but I’m trying to find a way in which design can facilitate the individuality that I see in other people. I want to encourage a niche of people who want to wear art. For me, a successful design combines the piece’s voice, my voice but also the wearer’s voice. I think that should be encouraged and that young designers should find their voice, no matter what the trends might be saying.” We are used to seeing something we like and expecting that there are hundreds of units behind the piece that everyone can have. As I speak to Yamkela, I understand that her opposition to this idea is not because she wants any kind of exclusivity in her work; rather, she wants to be able to create with the inclusion of individuality at the forefront of her work.

On the subject of sustainability, Yamkela reflects on the mindfulness that human beings once had around clothing, “our parents used to keep clothes for their children. They would mend and preserve what they had. If we look at our fast trend cycle moves and our throw-away culture, I want to find a way to create heirlooms that can go back to our appreciation for fashion.” I ask Yamkela, as an artist, why fashion is her medium? To which she says, “it sounds simple, but if you dress well, the chances of you having a good day are really high. Clothing is a protective barrier and you are within yourself, trusting and loving yourself. I’m really interested in fashion as this way of honouring who we are and showing who we are to the outside world.”

When Yamkela graduated, she knew that she had to find her way in the fashion industry. This daunting task was met with an internship at Superbalist.com – a space that she owes a lot to in teaching her the ins and outs of commercial fashion production and selling. It is heartening to listen to her describe that as conceptual designers, there is so much to absorb from a commercial structure like Superbalist. It was around this time that Yamkela found denim as a malleable material for her work; and it attracted the attention of Redbat Posse, who selected her to showcase alongside other finalists at SA Menswear Fashion Week SS23. The initiative is a women-focused design program by TFG’s Redbat Jeans, in which young designers were given Redbat samples and offcuts and tasked to patchwork, experiment and re-create something totally new. For Yamkela this was the perfect opportunity. As she says, “doing my first fashion show with Redbat was amazing. It showed me that it’s possible to work in a brand-specific way and still retain my essence as a designer.” Initiatives like Redbat Posse suggest a future in which residencies and programs foster unique and truly innovative design is par for the course.

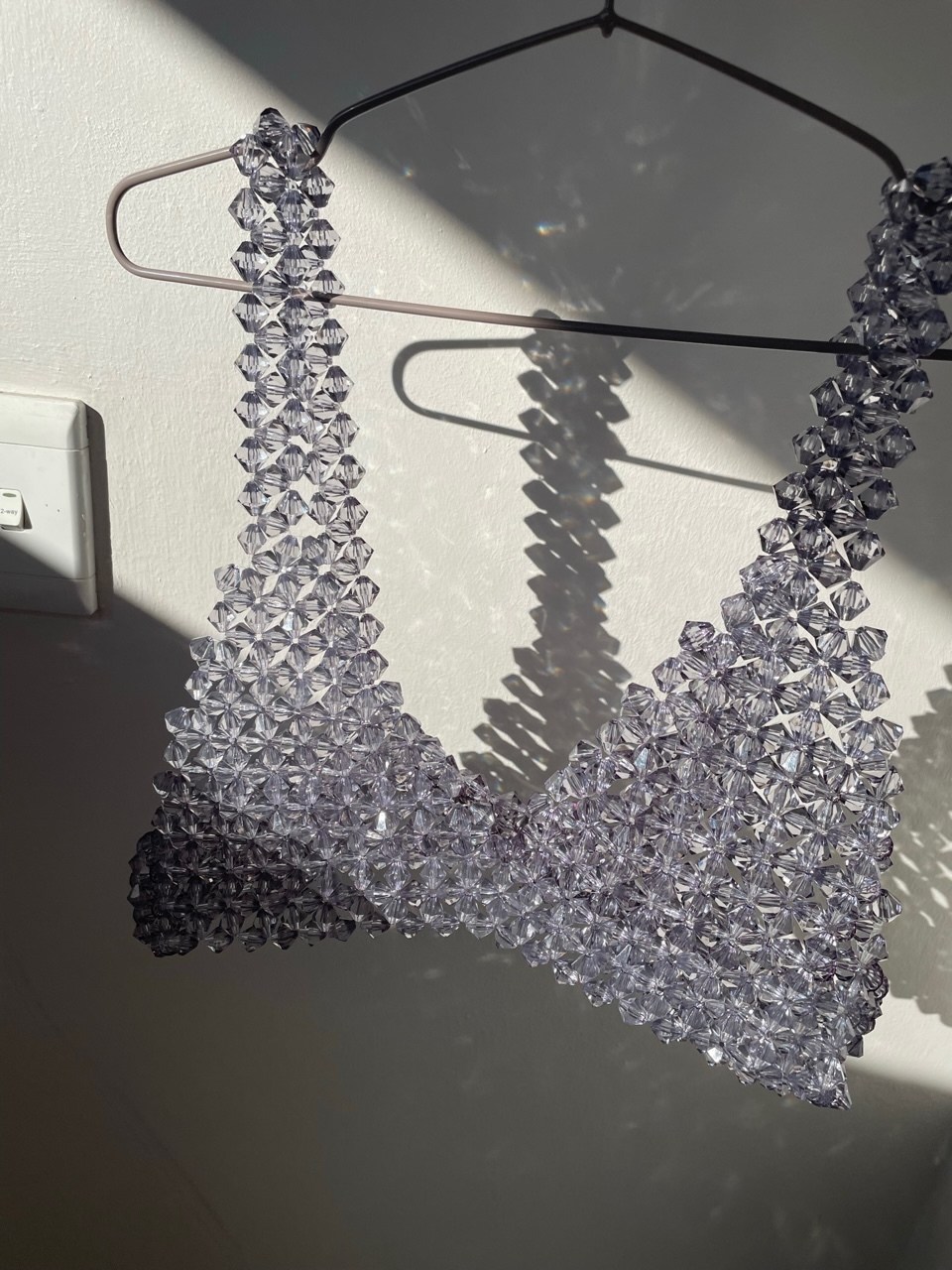

For Youth Day, Yamkela was part of Levi’s ‘Haus of Strauss Africa’ celebrations. Perhaps one of the most critical spaces of design-development through a brand specific lens, Haus of Strauss’ mission statement reads “The space serves as a physical embodiment of the Levi’s® brand on the continent, a place to build community engagement and nurture and celebrate African creativity. This is achieved by hosting educational workshops and enriching network-based gatherings. We invite creators and innovators into Haus to work with our team to customise garments. This results in unique pieces that have a personal connection to the creator and carry a story that will accompany that garment throughout its life.” Yamkela describes how she sent them a proposal and hoped for the best, off the back of a DM that she sent to their IG channel. The concept that Yamkela proposed was an homage to the Soweto Uprising that occurred 47 years ago, with a six-piece collection that celebrated the spirit of Blackness and the strides in creativity and expression that she and other creatives have been able to make. On this experience, Yamkela says “I was blown away by the experience. It’s my first exhibition and the exhibition is on until August at Haus of Strauss. I felt very seen and understood. It’s given me so much fuel to my fire, to move forward knowing that I’m on the right path.” I ask Yamkela lastly, what her hope for the future of young designers in South Africa is, to which she responds that “I want us to keep our clothes forever. To honour ourselves through our expression. I hope that our industry continues to allow creatives to have opportunities so that they don’t have to forfeit our talent, just to eat.”

Written by: Holly Beaton