When Rogers Ouma first laid eyes on the glossy pages of Vogue, he was in a quiet Kenyan village, flipping through old issues his cousin had collected like treasure. His cousin, a literature teacher with an eye for beauty, kept a modest stash of early-2000s fashion magazines that would prove formative. “I grew up between the city and the village, and it was in the village that I first encountered fashion magazines—thanks to my cousin who collected them. I’d look at images in early 2000s Vogues and think, ‘How is this even possible?’ That curiosity stayed with me,” he reminisces.

What began as a distant fascination with high fashion’s surreal gloss quickly grew into something more urgent: a visual hunger and a drive to make things just as arresting as he’s seen across those pages. It’s a fire that still burns now, years later, as Rogers has carved out his place as one of East Africa’s most compelling visual storytellers, though, less interested in trends than in timelessness, and always chasing the feeling that those Vogue pages first sparked. For someone now known for rich visuals and narrative flair, Rogers’ origin story is deeply spirited. The camera was always meant to find its way into his hands. A visiting Austrian mentor, while Rogers was tutoring maths, changed his trajectory in an instant. “He handed me a camera and said, ‘Let’s go for a test shoot.’ I had no idea how to use it, but I shot a thousand photos that day. They were all terrible, but he told me that’s exactly how it starts,” Roger explains, and this spark of experimentation—unfazed by perfection—is something Rogers has never lost. A high achiever at school, with multiple pathways ahead, Rogers rejected multiple scholarships to study abroad in the U.S., Austria, and India, choosing instead to stay in Kenya and pursue media studies in Nairobi. “I chose to stay in Kenya and enrolled myself at Multimedia University to study media and broadcast. That’s when I started shooting full-time.” Moving to the city was initially a rude awakening; within days of moving from Kisumu, he was robbed at the bus station—camera gone, savings wiped out. Rogers, already used to improvisation, simply borrowed a classmate’s camera and edited on his roommate’s laptop. “Having gear wasn’t going to stop me. I’d shoot when they were in class, then post the work on Facebook. Eventually, I grew a crazy fan base—people started paying attention.”

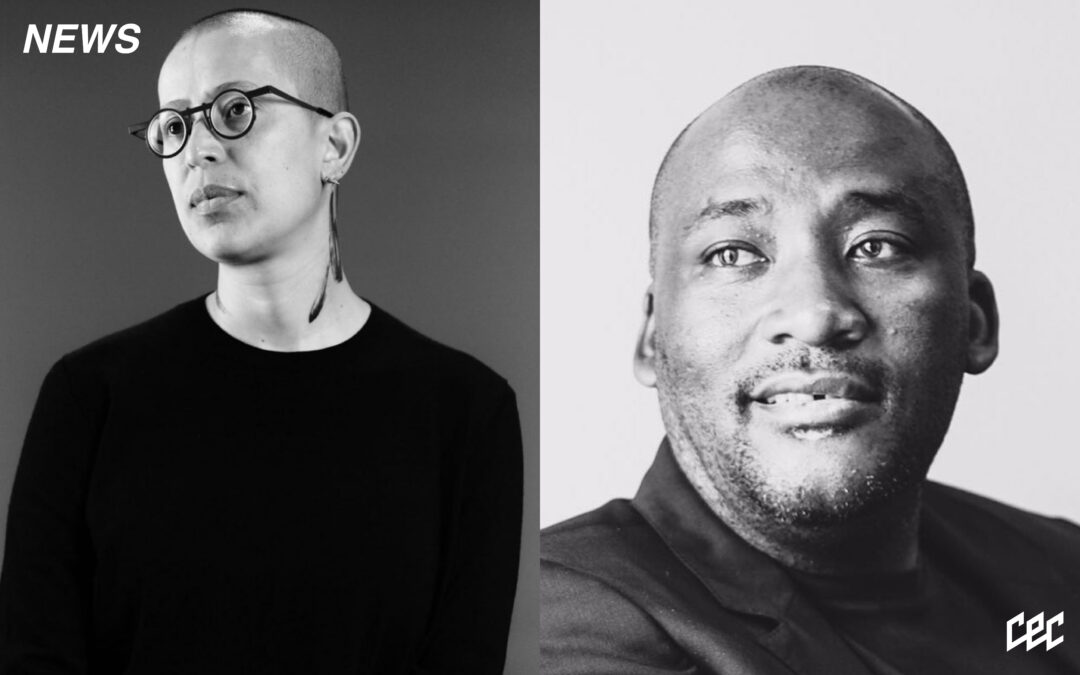

Photography by Rogers Ouma

Imbued with Nairobi grit, people noticed Rogers’ work, and granted him something of an underground cult-status. Rogers is an OG on the East African scene. His early work—self-taught —began gaining traction, and landed a feature on Vogue Italia while he was still a student. A huge full circle moment, to which Rogers says, “at first, I was replicating the kinds of visuals I’d seen in Vogue, and for people around me, it was something completely new. That visibility gave me momentum.”

Even as his technical skills evolved, Rogers’ vision stretched beyond beauty for beauty’s sake. Though principally a fashion photographer, Rogers’ subject matter spans across social, racial and environmental justice, all intersections he feels are intrinsic to African sartorial and creative identities, “I’m very open-minded in what I shoot,” Rogers notes, “90% of the time, I gravitate toward non-conforming styles. Highlighting queerness or social justice in my work can be dangerous in Nairobi—it’s illegal to be queer here. But for me, it’s important to tell these stories.” Rogers has had collaborators scrub themselves online after shoots for safety, their identities erased to avoid violence or backlash. One such project, featuring queer creatives, found itself exhibited in New York through OKAYAfrica, “That was major. It meant that stories from here, our truths, were being seen elsewhere,” Roger notes with conviction.

Rogers is deeply committed to the potential of East Africa, but points out that how the region is framed by the global creative industry is still problematic. “East Africa is still so untapped when it comes to fashion and creativity. There’s so much happening, but almost zero visibility internationally. That’s why collaborations like the ones I’ve created with The New Originals matter, they’re actually committed to amplifying voices from here. Eben and the team from TNO are one of few international teams who travel somewhere and collaborate directly with the creatives in that place.”

Rogers is strategic about changing this narrative, as he lays the groundwork for a more equitable creative ecosystem in East Africa. His call to action is simple; work with the local creative community. “If I have a client who wants to shoot in a different location—Lamu is there. Mombasa is there. I’ll take care of everything. We have equipment, we have a team. If you want to transport something to Lamu, I know people who fly jets. If you want to shoot in the Maasai Mara, I know the people, I know the way there.” This issue is intimately tied to the continual tensions and reclamation of ownership on the continent. Rogers recalls international productions parachuting in and using Kenyan soil as backdrop, without engaging local talent. “There was a day when a huge brand flew in an entire crew, and the only locals on set were two of my friends—one a makeup artist and designer, and the other assisting by carrying the umbrella. That’s it.”

Rogers’ own education in the importance of authorship arose from his background in humanitarian-led news. While studying, Rogers landed a job at Camera Pix—an esteemed Kenyan production house founded by the son of legendary photojournalist Mohamed Amin. “Being employed in that company gave me a lot. People in my class were in lectures; I was on planes, travelling across Africa. I used to film for CNN, BBC, Al Jazeera, NGOs—all of that.” Those years on the ground, immersed in real stories, taught Roger how to find the human thread in every story, to document without spectacle, and to shoot with a sensitivity and respect for the context and people involved. This hard-won documentary sensibility has never left his fashion work, as is evident to the deeply enriching and compelling portrayal of his imagery; “we’d create human interest stories, political stories, health stories. That’s why my fashion photography looks like a documentary. Even when I’m shooting fashion, I’m telling a story.” As Rogers emphasises, he has worked on sleek commercial campaigns—products, clean backdrops, imbibed by sterile minimalism—but these briefs don’t ignite him the way fieldwork does. “I can shoot the fancy stuff, clean backdrops, whatever—I’ve done those campaigns—but I won’t show them. What I want to show is the documentary side. That’s what makes it all click for me.”

Photography by Rogers Ouma

Even when his peers were preparing for final exams and graduation ceremonies, Rogers was out in the world, already working. It is precisely this expansive vision and determination that has brought Rogers to South Africa, to live between the two regions,“South Africa always had something for me because of the access, and the creatives bending all these norms and everything,” Rogers explains, “I’ve seen crazy stuff being done in South Africa. If I can be free and shoot, that’s me. You will find me there, and that’s what South Africa offers in constant supply.”

For Rogers, the dream is to facilitate the kind of burgeoning creative economy in East Africa that already exists in places like South Africa. His perspective is a poignant reminder of our relative freedom—both creatively and politically—and the importance of access in shaping artistic futures. I’m reminded of the continued work for liberation all across the continent: the ability to create boldly, safely, and without apology, and with the kind of respect and opportunity that Africa deserves on its own terms; far beyond the systems of voyeurism and culture-vulturing that still exist. South Africa’s cultural infrastructure and cross-disciplinary networks offers a rare scaffolding for artists to grow and thrive, despite our need for so much more in this respect. I’m reminded, too, that each creative is working towards a broader model for the future that resists extraction and instead nurtures creativity from within.

So what’s the endgame, I ask Rogers, after all is said and done? Rogers intimates his vision for seizing this moment of renaissance on the continent, is a hope to be part of a lineage of ‘greats’, who changed image-making on the continent; “if you backtrack to James Barnor or Malick Sidibé, that’s the vision. It’s timeless. I want to be in my 80s, and the kids are looking at my images the way I looked at their work, thinking ‘oh, this is historic’. I just wanna shoot and create cool stuff that stands the test of time.”

Photography by Rogers Ouma

Written by Holly Bell Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za