Being an artist seems to be a predetermined, destined path. At least, in certain conversations I get this sense; with an artist like Alka Dass, this feeling is overwhelming. It has only been in recent years that a career in ‘art’ or ‘creativity’ has become in any way acceptable to the older generations that have raised us. Alka was no exception, having to fight to take up the mantle of this calling through financing her own tuition at DUT (Durban University of Technology), facing the disapproval – or rather fear – of her family to pursue something seemingly frivolous. Yet, Alka continued to pursue the pull of a subconscious, elusive thread that now sees her archiving the fabric of who she is, her wider context of origin and the mean-making of craft, through many means of etching and alchemising. A thread well-pulled, I say. As Alka says of her innate fascination with creating, “I was in grade one and they had asked us what we wanted to be when we grew up. I didn’t know the term ‘artist’ then, but I replied that ‘I want to own all the crayons in the world so I can draw all day’. The parents were in the class and my mum gasped! She was so shocked and said that I needed to share crayons with other kids. Now, my mum always brings up the story in relation to being an artist now.”

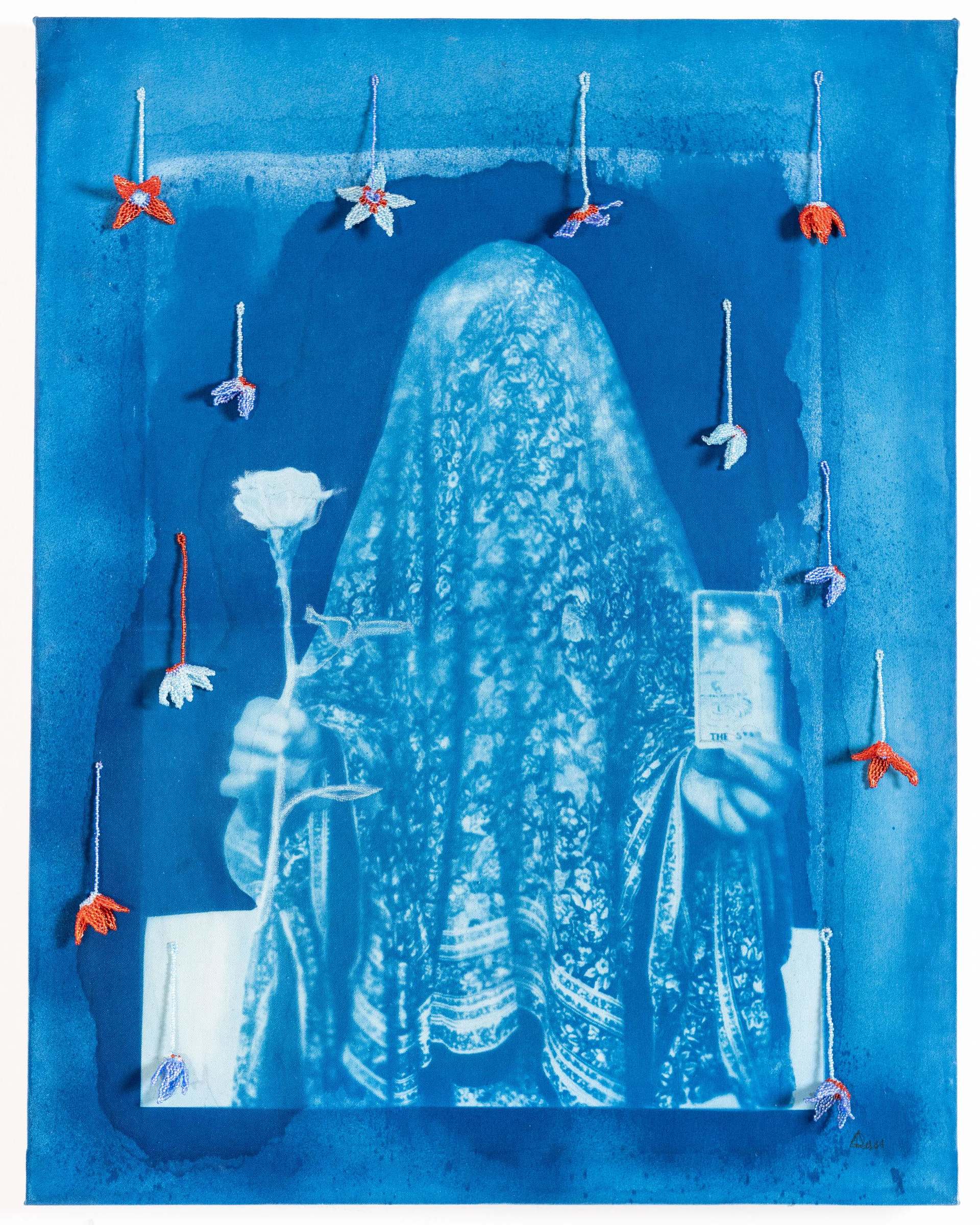

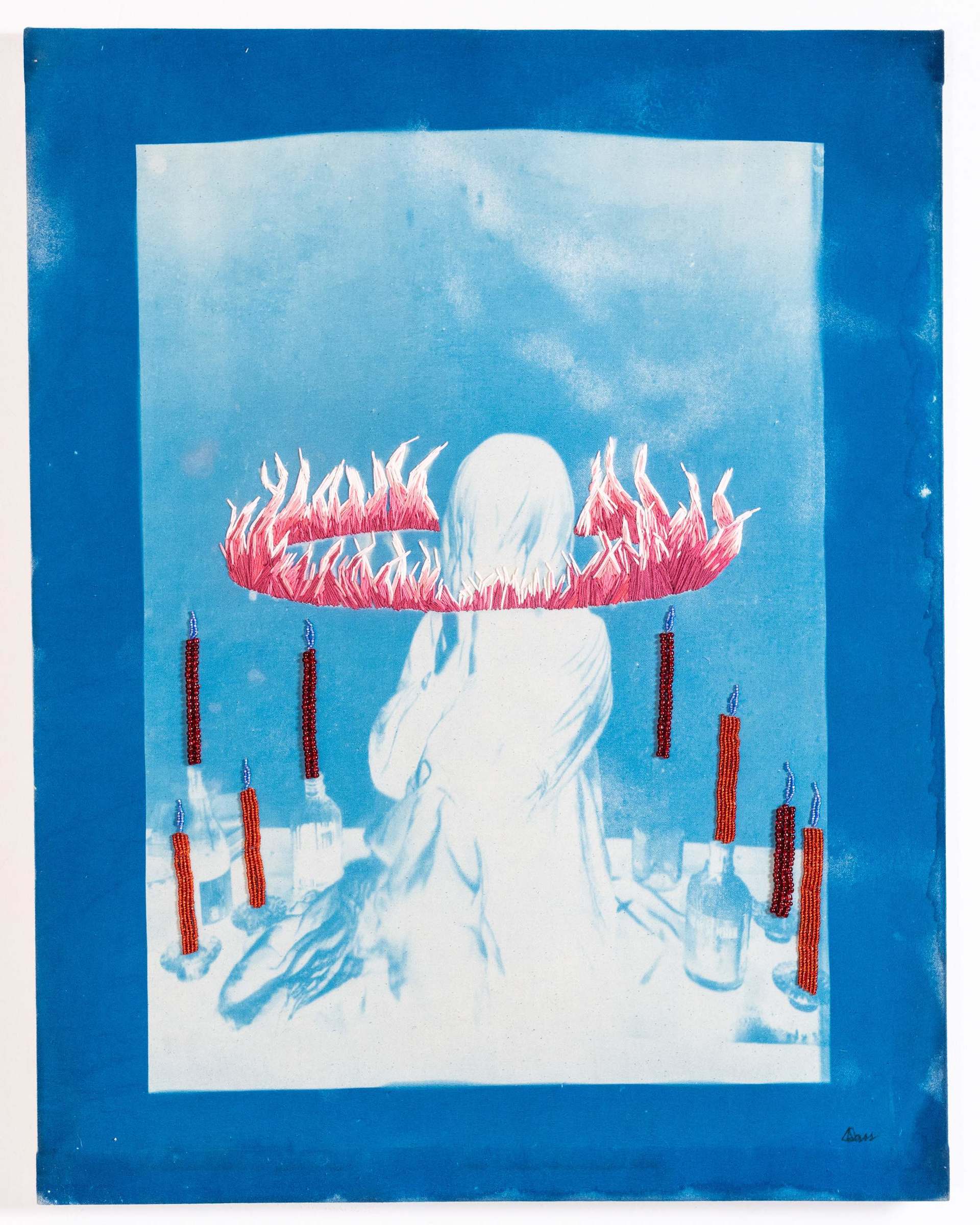

Central to Alka’s practice is her experimentation of the hand-crafting practices that she grew up with. It was not initially obvious to her that this was perhaps an inter-generational boon, passed on as the secret coding between women to enliven the home or adorn one another, Alka explains that “my mum was a nurse in the local government but she was always very creative and crafty – she quilted all our bedwear and my grandmother was a seamstress. She used to make all her and her sister’s bridalwear and outfits.” and that “I saw a lot of that growing up. Now, my practice is so informed by textiles but I never thought that would be an outcome for me. I see now how much I was informed by the women around me with thread and needles. I also think I had internalised the notion that crafting and textile work isn’t ‘serious work’ – its soft things, quilting, beading on clothing – it was just ‘women’s hand craft’. The older I’ve got, the more I just want to contextualise these crafts as fine-art. Why can’t handcrafts be fine-art?” Alka’s practice touches on the truth of how we have come to categorise creative practices. It seems, the delegation of certain mediums (such as oil painting) versus the intricacies of beading have been subject to the division of patriarchal viewpoints of ‘worth’ or ‘status’. When I view Alka’s work though, I see the richness and depth of the finest order; intimacy mapped out by cyanotype fervour, met by layers of beading, stitching and intentionality.

Alka Dass in studio photographed by Laurrel Alison @myheartisyours

Finding herself drawn to needle and thread, Alka describes that “I had always liked the thought of a needle coming in and out of fabric. It’s a fascinating thing. I started experimenting with stitching when I was studying fine-art at DUT (Durban University of Technology), it was mostly words at that stage.” The mindfulness of this aspect of Alka’s approach allows a kind of mindfulness or meditative influence in her pieces, saying “I think the method of it is very cathartic. Your mind goes on its own journey and with stitching, you gain something new and lose something old – the old form of whatever you’re stitching used to be. There has always been some thread work in what I do.”

Alka’s identity as a South African Indian, queer woman was not initially her thematic concern. Meeting up against the politic of one’s identity is also to demand autonomy of choice against the pull of tokenisation so often projected on Black and Brown artists,

“I came up against what I was told to focus on as an artist. I was the only Indian person, and only Indian female, in the whole fine-art department from first year all the way to Masters. My lecturers kept saying ‘you should unpack that, you should talk about your identity!’ and my reaction was, ‘don’t tell me what to do!’ I didn’t want to be the token representation or to be boxed into one narrative. At that time, what irritated me more was that only about 30% of the department was female – this irritated more than being the only Brown person. So I started tackling that as my initial subject matter.” Alka eventually realised, to her chagrin, that “I left university and I was like – oh my god, I do want to talk about my identity! They were right. I hated it so much. Finding my voice as a Brown, queer woman from Durban in the artistic landscape of South Africa was difficult. I used this experience to decode what it meant to be a female, queer Brown person forming a fine-art career.”

It has been written that Alka Dass investigates the ‘psychological and cultural spaces that women of colour traditionally occupy’. In our conversation, Alka puts it as something that came as a surprise to her, that “I didn’t realise that I was using my own language of textiles to talk about the lineage of my mother and grandmother.” In her initial articulation, Alka began incorporating old photographs into textiles that her grandmother made as a young bride, such as handkerchiefs and crocheted doilies to decorate the house. Moving back home with her grandmother during lockdown after spending a few years in-residency between South Africa and France, Alka was eventually asked to move her over-spilling studio from her bedroom and lounge into the garage. This saw her encounter boxes of old photographs of people she knew, “they really moved me, they made me cry. I realised I hadn’t seen any of the people in the photographs as young children and people. I knew them as their older selves. They were so beautiful and my grandmother – who doesn’t deal well with emotions – she came to sit down and remedy the situation by telling me the stories of each person in the photographs, as if they were sitting in front of her. She spoke with such intimacy, telling priceless, silly stories. It made me so excited to work with them.”

We are the expression of those before us and this aching truth is what binds us together cellularly, somatically and spiritually. The profundity of that moment in the garage with her grandmother is the bones of Alka’s current practice today, “one of the stories she had told me is how her mother would wake up every morning and go into the garden, talking to the plants and encouraging their growth. I pointed out that she does the same now, in her own garden. I ended up combining the photographs with pressed flowers grown by my grandmother’s hands. I felt like the photographs and the flowers had the same brittleness and fragility, and both were archival, so bringing them together opened up my perception of a mixed-media approach.” What Alka has done, intuitively, is respond to her family’s disapproval with visual love letters of who they are and in doing so, preserving the inarticulable importance of their cultural, creative and existential expression. As South African, as Indian, as people – as daughters, sons, mothers, fathers and community. It is often said that it usually takes just one child born to begin unravelling and releasing generational weights; I think of Alka formulating her practice over time, rising to the occasion armed with pressed flowers and visions of the women and family before her.

Alka Dass Catalogue, Red crest reign. Latitudes Art Fair. 2023. Photographed by Paulo Menezes @paulomenezespictures

Alka Dass Catalogue, Eyes wide shut. Latitudes Art Fair. 2023. Photographed by Paulo Menezes @paulomenezespictures

Alka Dass Catalogue, Milkweed contusion. Latitudes Art Fair. 2023. Photographed by Paulo Menezes @paulomenezespictures

Right now, Alka is heavily involved with the traditional practice of cyanotype. Historically this is a method reserved for architectural blueprints, before it became a photographic method in the 19th century. Cyanotype is a photographic printing process that uses sunlight to create distinctive blue and white images. It involves coating a paper or other surface with a light-sensitive chemical mixture, typically containing ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide. When an object or a negative is placed on the treated surface and exposed to UV light, a chemical reaction occurs, resulting in a blue print. As Alka explains, “I loved the blue so much. There is so much packed into the colour blue. In my culture, there’s three gods that created the world. One of them – Shiva – is blue. Originally he was brown, but he decided to drink all the impurities and toxins of the earth that were in the water. Shiva had realised that mortals needed some assistance with the balance of evil & good in the world, and that solution resulted in his blue body. With cyanotypes, you rely on this alchemy of the heat and light of the sun and then water to expose the image.” The poetics of drawing up her family’s lineage and blueprint – as blueprints – tending to with such meaning and ritual, renders Alka one of South Africa’s most critical storytellers in South African art.

Alka is part of one of the most important spaces that I think exists in South Africa’s creative landscape. Kutti Collective is a South African art collective, composed of Desi artists across the gender and sexuality spectrum. As Saaiq’a wrote for Document, “Kutti Collective is a space where we mediate our art and identities; and support one another on a personal level as well as in our respective artistic practices. As a collective comprised of non-binary womxn and LGBTQ+ identifying artists, we are continuously reclaiming our minds, bodies, and identities within cultural, public, and social structures; which are largely sustained by colonial legacy and patriarchy.” As Alka describes how the collective formed, “I was doing a solo with a gallery who I will not name. One day the owner came up to me and said that they loved my work but that I should think about ‘dial down the Indianness’ in my work. That it wouldn’t sell well or appeal to their clients. I was shocked. I bumped into Tyra Naidoo at Joburg Art Fair and we spoke about this incident and our shared experiences. I thought, let’s start a collective? Why should we have to navigate these spaces alone or in isolation and why should I have to feel uncomfortable being myself? Initially Kutti was a group chat in which we shared our experiences. It was great finding that there’s a bunch of us queer, Brown people that can be weird and wonderful together.”

With much more ahead for Kutti Collective and her own individual practice, Alka Dass is committed to composting the discomfort that she felt stepping into her artistic calling. From it, nourishing soil – sun, water – and air, will define Alka’s work as wholly and irrevocably vital for the lifeforce of South Africa’s artistic and multicultural future.

Written by: Holly Beaton