We’re a predominantly African fashion column, but every so often we dip our toes northwards, and as a principle of this column, decentring our gaze from the West is paramount. Naturally, with much of the continent positioned within the Global South, the parallels and solidarities between Africa and Asia are as revealing as the contrasts; and while we’re always attempting to depart from hegemonic notions of any one place, it felt as though a broadstroke overview was very much in order.

Both Asia and Africa have historically been cast as labour pools for Western markets, both have been flattened by reductive narratives, and both are now asserting themselves as sites of cultural authority. Today, we sit alongside China and India in BRICS (with more Asian countries joining), as a multi-lateral trade organisation expressive of the ties between our ‘global south’ geographies of power and possibility.

Asia has existed in the Western imagination as a place of endless supply chains: a factory floor feeding the appetites of Paris, Milan, London, and New York. Its role is generally framed in purely extractive terms, as if the continent’s function begins and ends with cheap labour and outsourced manufacturing. This has been our perception, but it does little to acknowledge the agency inherent in Asia’s design landscapes. It’s also a myopic view, and as you know, here at Interlude, we’re always aiming for storytelling that complicates the easy clichés and honours the multiplicity of design cultures.

The reality across Asia is dynamic, complex, and culturally significant. Asia has always been a wellspring of sartorial creativity in its own right, and the manufacturing possibilities vary significantly. From Shanghai to Seoul, Tokyo to Mumbai, Hanoi to Manila, designers are carving out space within global fashion; and still, this article is merely a glance at this vast topic, and the polyphonic reality of Asia as a continent. Multiplicity is the defining strength of this new landscape, with many voices and spaces recontextualising heritage, experimenting with futurist aesthetics, and refusing to be defined by colonial-era hierarchies or neoliberal scripts.

Angel Chen Studio, via @angelchenstudio IG

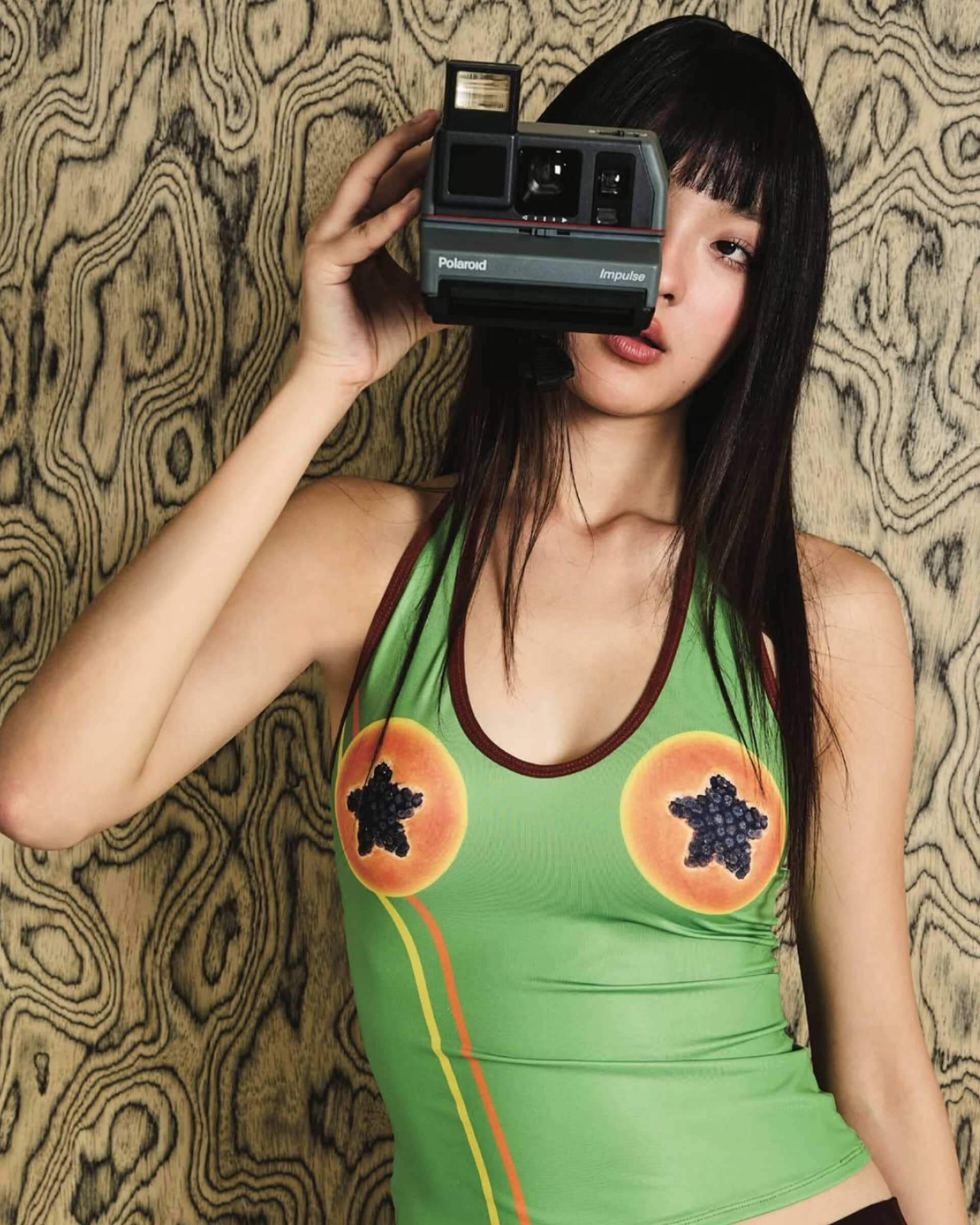

NORBLACK NORWHITE, via @norblacknorwhite IG

BLACKDOG via @blackdogbkka

No country illustrates fashion’s shifting dynamics more clearly than China. In the last century, its image was defined by scale — the sheer magnitude of its manufacturing output. “Made in China” has become shorthand for affordability, uniformity, and speed. Similarly, it came to mean disposability; fast fashion at scale, and clothing that could be bought cheaply and discarded just as quickly. Nuance is ever more important: this is true, and on the other hand, we cannot reduce an entire country or culture to an aspect of global supply chains alone.

In reality, China’s manufacturing ecosystem is highly stratified, and alongside the mass production that dominates global perceptions, there are regions renowned for specialist craft, luxury textile development, and small-batch production. Suzhou, for instance, is steeped in silk traditions, while cities like Shenzhen are home to tech-integrated fabrics and innovation labs that annually receive designers and brand-owners around the world for prototyping and access to material technologies yet to be scaled in Europe or the US. This reveals the range — from artisanal heritage to experimental design — complicating the idea that “Made in China” monolithically denotes lack of quality, or inexpensiveness.

A deliberate repositioning of China as a tastemaker in its own right (and I must note, this has always been the case — I mean here specifically in the context of the global stage), has been both intentional and inevitable, tied to the country’s expanding soft power. Under Mao’s China, fashion was bent into the service of the state’s political vision: the Mao suit as a uniform of equality and collectivism. Revolutionary zeal dominated the clothing of China’s recent political history (during years of relative isolation from the world) and dress became an embodiment of the values of the nation. In the decades since, the shift has been dramatic; with economic liberalisation, China’s rapid growth has uplifted around 800 million people out of poverty over the last forty years, into a newly empowered middle class, ultimately redetermining aspirations and consumer behaviour. One of the ways this was achieved was through positioning themselves as an indispensable manufacturing centre in the world. This rising demographic, armed with disposable income and a hunger for cultural capital, has become a driving force behind China’s luxury market and, increasingly, the country’s influence on global fashion.

Among China’s distinct design voices, Angel Chen, a Central Saint Martins graduate, has become one of the leaders of the neo-Chinese wave; her explosive use of colour, eclectic patterning, and experimental textures have earned her international acclaim and collaborations with brands from H&M to Canada Goose. SHUSHU/TONG, the Shanghai-based duo of Liushu Lei and Yutong Jiang, both trained in London, have carved out a cult following with their hyper-feminine yet subversive aesthetic; bows, ruffles, and babydoll silhouettes that play on the tensions between innocence and power. Meanwhile, Zhaioyi Yu represents a wildly conceptual approach, with a firm vision as a couturier with his signature, cascading sculptural forms with Chinese symbolic references.

Asia truly does refuse monolithic characterisation: its fashion is deeply local and unflinchingly global, rooted in tradition and perpetually reinvented. For instance, South Korea’s cultural presence has seen a rapid ascent, as the K-pop girlys will tell you. Seoul has emerged as a trend epicentre, propelled by the cultural phenomena of K-pop and K-drama, and designers like Minju Kim, whose voluminous constructions captured international acclaim on Next in Fashion, epitomising the essence with which Seoul’s digitally fluent, trend-hungry consumers often signal what the world will covet next.

Tokyo, by contrast, is contemplative, a city reared in an avant-garde lineage and philosophical rigor. As I have explored previously in this column, when discussing Asia’s global influence, Japanese fashion always comes to mind; and our western understandings of minimalism have largely been trained through the enduring legacies of Japanese visionaries such as Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto, and Issey Miyake. In Japan, fashion is a way of inhabiting, interrogating, and reimagining the world itself; to them, we owe an immense debt of creativity and conceptual daring.

LiFE DESiGN poster interventions in Manila, via @welife.design IG

Angel Chen Studio, via @angelchenstudio IG

Zhaoyi Yu via @zhaoyi.official IG

In India, Sanjay Garg’s Raw Mango has recontextualised handloom, embroidery, and the sari, proving exactly how one can preserve a sartorial tradition for the future. NorBlack NorWhite, an absolute favourite, was founded by Toronto-born creatives Mriga Kapadiya and Amrit Kumar after relocating to Mumbai in 2009, and their reinterpreting indigenous crafts with streetwear sensibilities. The label has garnered international acclaim and their recent collaboration with Nike is among one of the greatest campaigns I’ve ever seen.

In Southeast Asia, Thailand’s BLACKDOG is a tastemaker brand, as they deliver a sense of Bangkok’s wildly cool and gritty youth culture. In Vietnam, SUBTLE LE NGUYEN is utterly divine; from Hanoi, they interrogate form through minimalism, and suffuse Vietnamese heritage with experimental techniques. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, Construction Layers merges Filipino craftsmanship in a dreamy, avant-garde way. Collectively, these movements articulate Asia’s creative breadth: couture and streetwear, futurism and revival, all unified by a refusal to be defined externally, and asserting authority over their own sartorial narratives. The throughline? The unflinching commitment to preserving some form of tradition for the future, technically and aesthetically. I loathe the word ‘timeless’ in the context of fashion, but as they say; if the shoe fits.

The energy of fashion’s pan-Asian expression is precisely in its refusal to be singular. There is no “Asian fashion” in the way we’re sometimes inclined to categorise. Instead, there are many voices, each rooted in place yet resonating globally. This multiplicity challenges the idea that a single narrative can ever capture the dynamism of the continent; and this is precisely what Africa is demanding, too. We are shifting the notion that the West is the site of creativity and the East is the site of labour, and we can see this play out with the way that Dazed China pushes editorial boundaries, and Filipino studio LiFE DESiGN recently went viral, live from Manila, with their iconic, meme-style fashion tarps as an ongoing humour-laden, tactile intervention (please do a deep dive, I beg).

To understand global fashion today requires the ability to see Asia as a full-spectrum ecosystem of design, production, and cultural authority. With the advent of sustainability as inherent to the conversation in fashion usually pinned to the Rana Plaza Collapse in 2014, where over 1,100 garment workers lost their lives in a preventable factory collapse in Bangladesh, we are so in need of a new ethos of manufacturing and ethics of consumption that traces multilateral channels around the world. It will take our recognition that innovation circulates in a loop, in which practices in Dhaka, Delhi, or Guangzhou are as instructive to Paris, Joburg, Lagos or New York as the other way around.

Recognising this shift allows us to imagine a fashion world that is interconnected; with influence shared, creativity as collective, and the future of fashion as full of possibility. J’adore.

Written by Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za