I recently had an experience where I introduced myself to someone, “Hello, I’m Casey. It’s lovely to meet you”, I said in a friendly and clear tone. “O hello, JC, it’s good to meet you”, the person replied. His tonality carried a sense of certainty and security that he seemed awfully proud of. “Sorry, maybe you misheard. It’s Casey, not JC,” this time, making sure there wouldn’t be any chance that the person might mishear me. “Ahh, like a K and C, why don’t you use your full names?” the person asked. Needless to say, I was perplexed by someone else making such broad-stroke assumptions about my name, how it is spelt and its meaning. To be frank, the whole experience left me pretty hurt. There’s something so intimate and intrinsic in the way our names or chosen names are linked to our identities. This feeling of rejection made its way deep into every fibre of my body. A feeling that the person I was interacting with failed to acknowledge and accept my very identity, that they had in some way rejected my sense of self. I snapped back into the moment to be met by the final nail in the coffin. “I’m going for a drink, it was good meeting you, JC.”

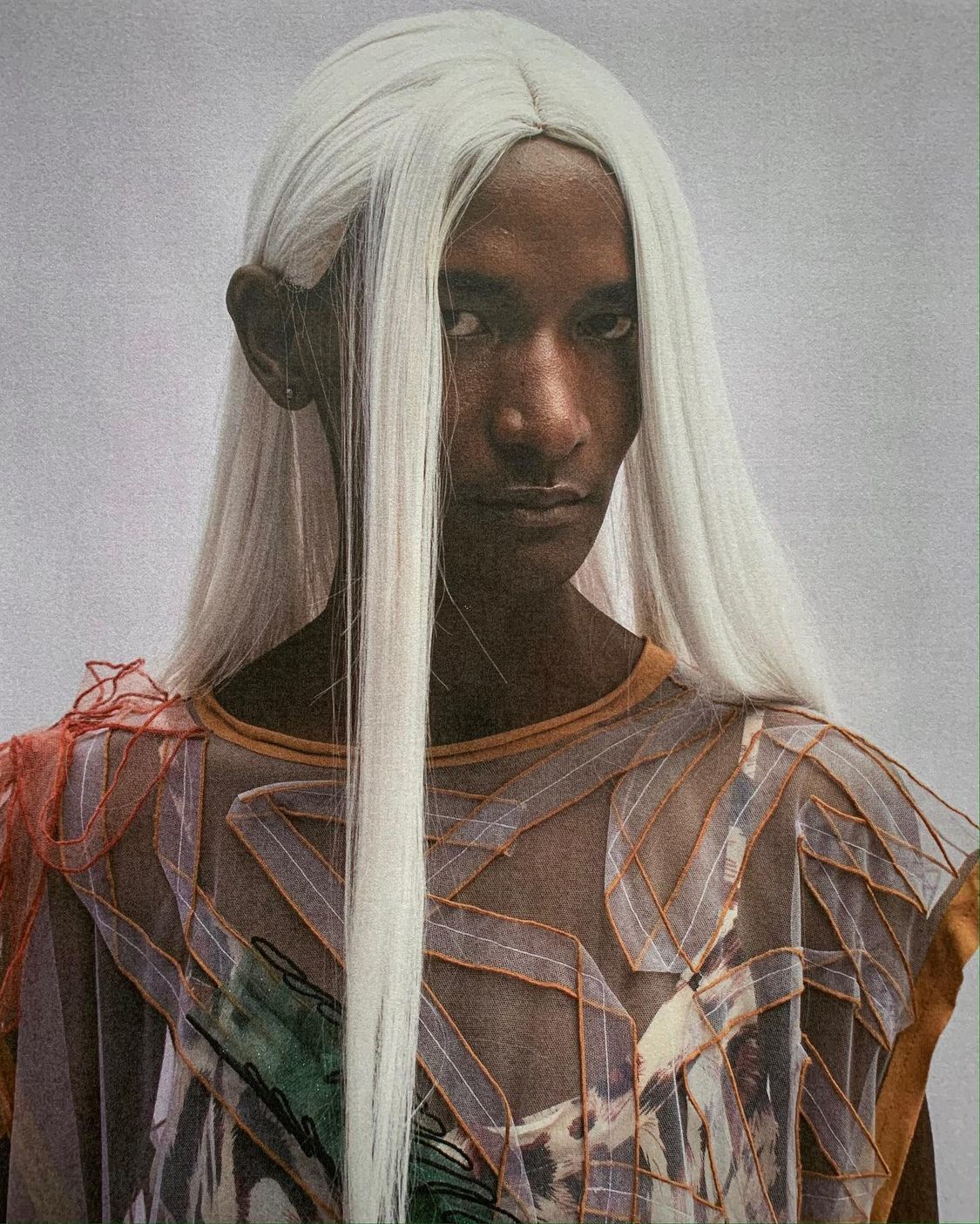

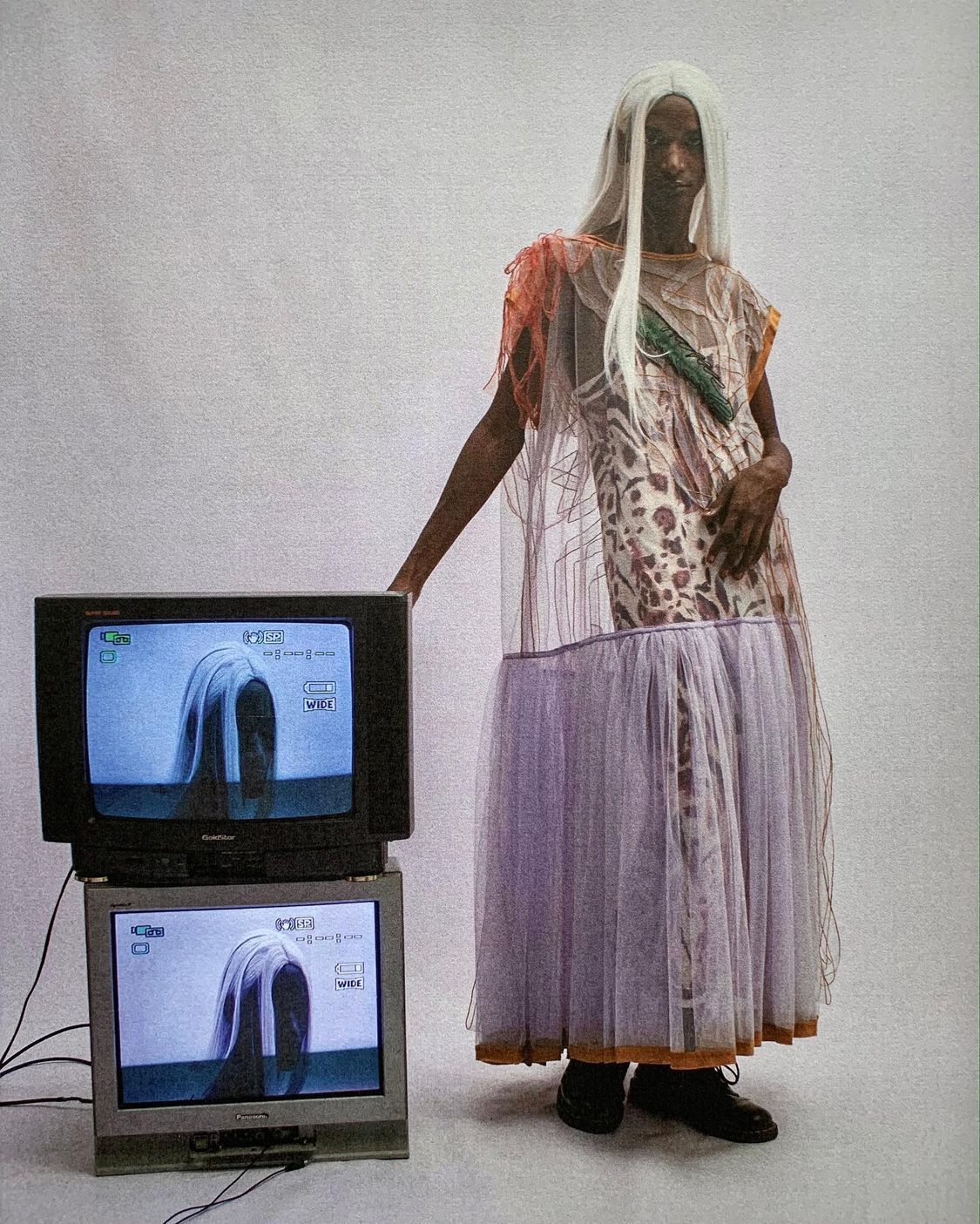

For: Contributor magazine Styled by Ky Boshoff. Model: Thapelo Mofokeng. Wearing: Trotse Tert. TV visuals: @nikibotha

Although my long-winded, silly little sob story may seem like a plea for some attention, that short interaction at least attempts to serve as a poignant albeit silly starting point to a broader and far more important conversation regarding identity and the way in which the words and language we adopt go a long way in affirming and unfortunately also denying our self-actualised identities. Maybe I place a far greater emphasis on the weightiness of words due to my job, where words and sentences are carefully curated to paint thoughts and musings across a blank canvas, but history has often showcased just how destructive or uplifting the tongue can be. Words, in truth, can be the very foundation we cling to in hopes of building a better future, or they can be the sledgehammer that tears down all possibilities. It is a tool used to spread love, care and affection or a weapon that cultivates hate, disdain and anger.

For: Contributor magazine Styled by Ky Boshoff. Model: Thapelo Mofokeng. Wearing: Trotse Tert. TV visuals: @nikibotha

With this in mind, I want to talk today about pronouns but, more specifically, the importance of preferred pronouns and why all of us should take the utmost care in respecting and acknowledging whatever pronouns someone chooses. I purposefully decided to share my stupid little story in the intro because it is something we can all relate to. Someone has gotten our name horrendously wrong at some point in our lives. Whether that be the often comical spelling of your name on your Starbucks order or that one colleague or client that seemingly uses a different spelling of your name in every email. Some may find these little errors funny at first, but if it’s something that happens over and over again, it ends up being an incredibly infuriating and hurtful experience. My question then to us all is if we place such importance on being correct when we address people by their names, why do we seem not to use the same care and consideration when we use pronouns? This becomes all the more perplexing when we look at the very function of pronouns within language. In this context, pronouns are used to replace someone’s name when referring to them. When one considers this, it would seem ridiculous to refer to someone by the wrong name, yet there is often a disregard for using people’s preferred pronouns. Just like given or chosen names, pronouns are intrinsically linked to one’s identity and thus should be treated with the same amount of care and consideration. As paediatric psychologist Tabi Evans (they/them) states, “Using a person’s correct pronouns is important because it affirms that person’s identity, helps them feel comfortable in their own body, and shows that you respect them for who they are.”

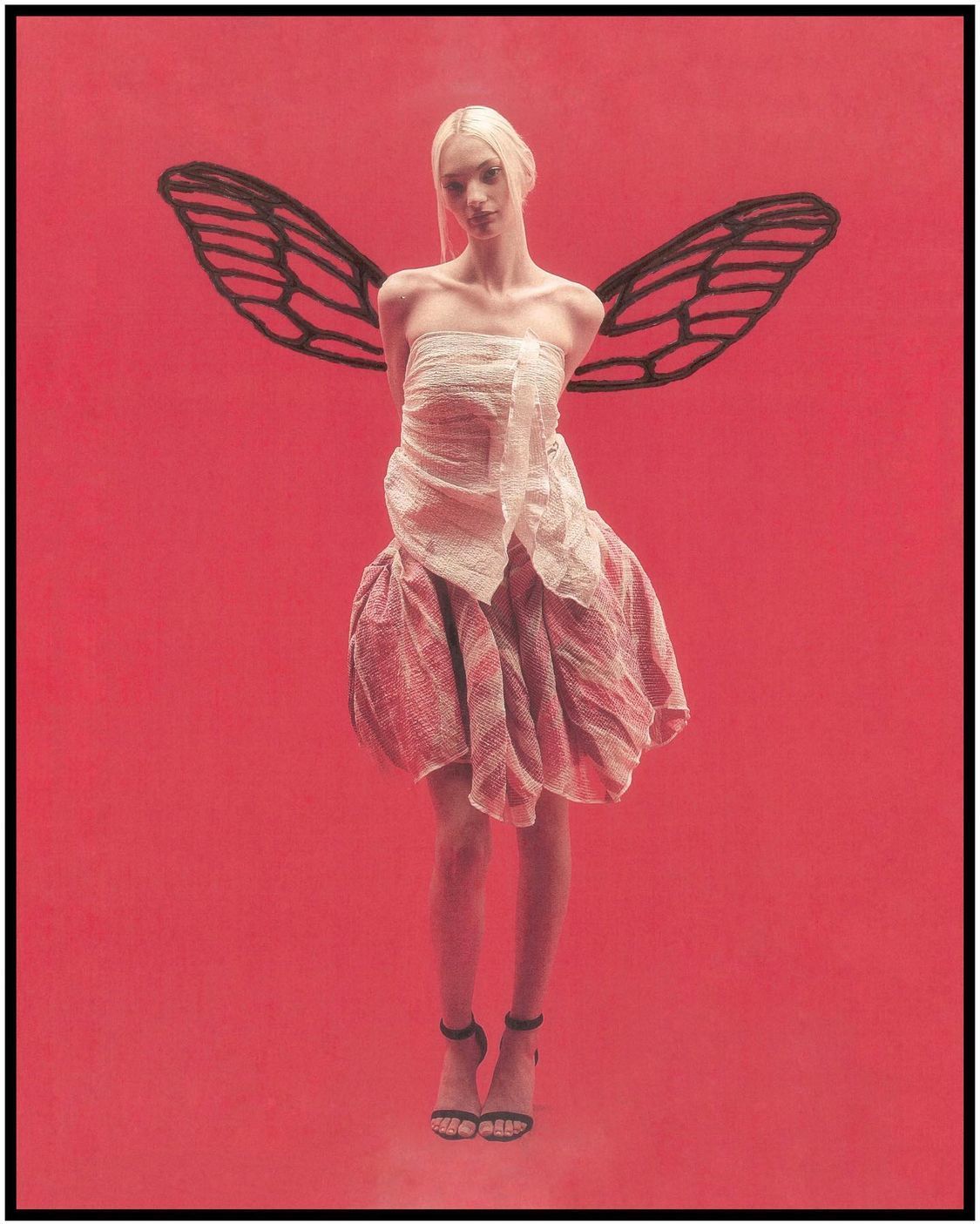

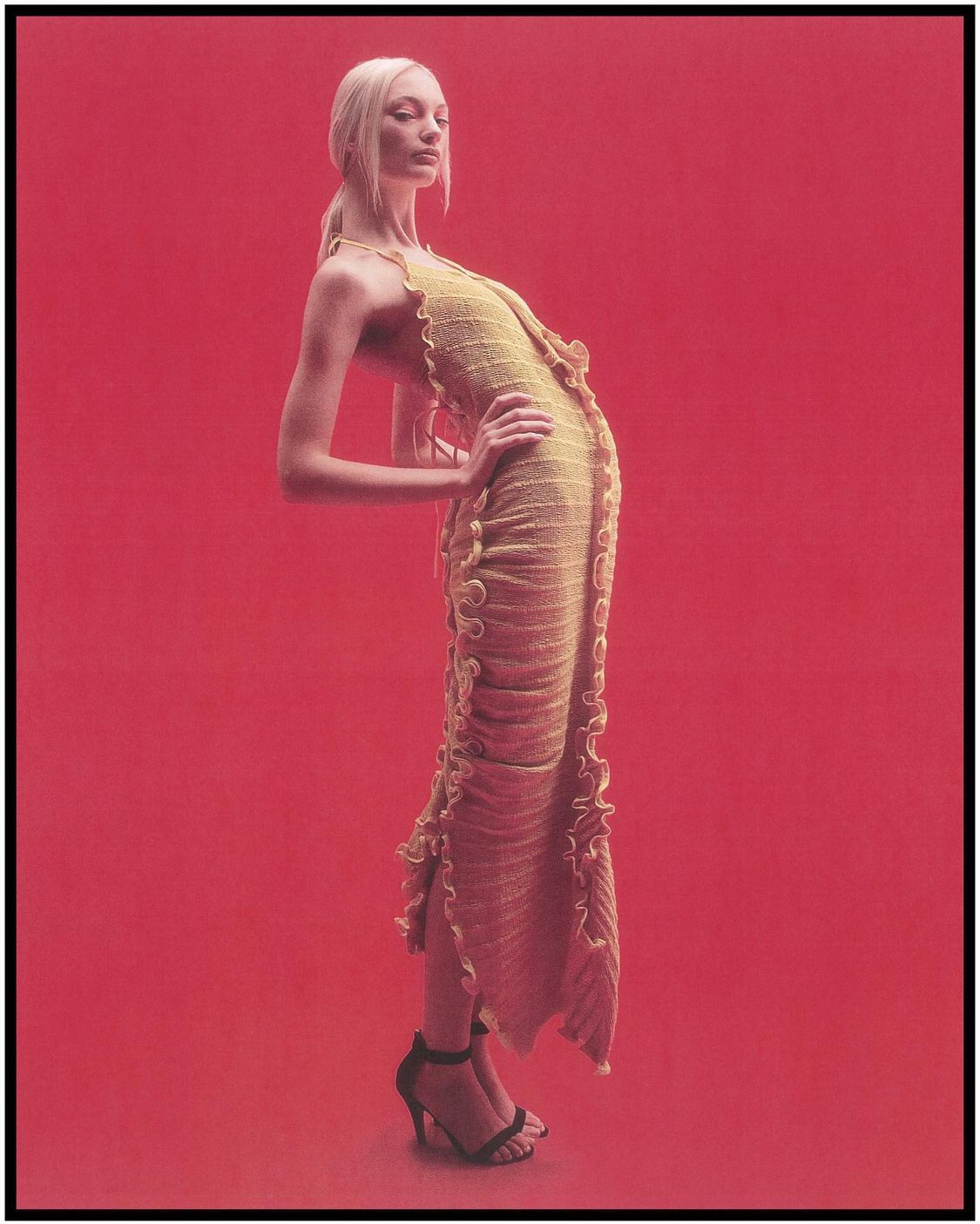

Fashion Director: Ky Boshoff. Fashion Assistant: Teagan van Zyl. Hair & Makeup: Toni Greenberg. Model: Bethany De Waal. Published by @twygmag. Wearing:Lara Klawikowski

I think the issue often lies in the fact that many people believe gender and sex can be used as interchangeable terms. This is something that is inherently problematic, as the two terms don’t correlate at all. Glen Hosking (he/him), a senior clinical psychology lecturer at the University of Victoria, explains it as such. “While people may use the terms sex and gender interchangeably, they mean different things. Sex refers to the physical differences between people who are female, male, or intersex. A person typically has their sex assigned at birth based on physiological characteristics, including their genitalia and chromosome composition. This is distinct from gender, which is a social construct and reflects the social and cultural role of sex within a given community. People often develop their gender identity and gender expression in response to their environment. While gender has been defined as binary in Western culture, gender is on a broad spectrum; a person may identify at any point within this spectrum or outside of it entirely. Gender is not neatly divided along the binary lines of “man” and “woman”. People may identify with genders that are different from sex assigned at birth, some people do not identify with any gender, while others identify with multiple genders. These identities may include transgender, nonbinary, or gender-neutral. Only the person themselves can determine what their gender identity is, and this can change over time.”

It is apparent that the younger generation is far more accepting and determined when it comes to respecting the preferred pronouns of their peers, friends and colleagues. Without shifting blame onto the older generation, I think some myths need to be dispelled regarding gender identity and its prominence in modern discourse. So often, we hear the excuse that kids today are just making things overly complicated or that we are simply making up new gender terms for no reason. First and foremost, I think the article up until now has proved why these terms and expansion in language are necessary with regard to gender. Secondly, I would like to dispel the myth that grappling with and exploring gender identity outside the traditional binary boxes is somehow a new phenomenon. In truth, many indigenous communities had far more liberal notions concerning gender identity than the binary identities many people cling to today. As Nigerian scholar and sociologist, Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí (she/her) states, “gender as a concept didn’t even exist within Yoruba culture and society before the arrival of Western colonisers.”. Similarly, we may look at the fact that Native American societies acknowledged and highly respected a gender spectrum that included female, male, Two Spirit female, Two Spirit male and transgendered individuals before the arrival of colonial powers.

Admittedly this article may come across as a cis-gendered, heterosexual, white Afrikaans man seemingly telling you what to do and why it is important and who the hell am I to even do that? However minor these issues may seem to some, you have to consider that for many others, these issues are inherently linked to their own safety and sense of self. Elle van der Burg (she/they) is a trans woman (albeit she is far more than that) that I have had the absolute pleasure of meeting and talking to. She puts this sentiment beautifully, “at the end of the day, as trivial as personal identity can seem to people on the periphery, it is ultimately a matter of life and death for the people who are on the receiving end of being misgendered.”

Writer and dear friend, Lindiwe Mngxitama (she/they) poignantly reminds me of the meaning laden within correctly and respectfully speaking to and of people,“We need to meet people where they are at. We speak about gender in a language that is very much white, academic and inaccessible to many people, and I think that can be threatening, particularly in this age of political correctness, where we are not holding space for people to arrive at these conversations imperfectly. I’d rather someone arrive imperfectly and show up to do the work, show up to learning rather than needing them to show up to these conversations perfectly using the right discourse that we get from academia. At the crux of it, it is holding space for people’s humanity, holding space for people to articulate who they are without imposing a violence of wanting to understand them from your perspective.”

It is in this very sentiment that I want to root this article. We may arrive imperfectly into discourse and discussion that seem new and challenging to us, but we owe it to those around us, regardless of where they fall on the gender spectrum, to arrive willingly in the first place. There is no time like the here and now to start our journey of unlearning narrow-minded ideas and expanding our care and compassion, for it is that sense of community that truly makes us human.

GENDER PRONOUN INDEX:

If you’re unclear, just ask.

A few standard ones to note:

He / Him : Someone who identifies as male

She / Her : Someone who identifies as female

They / Them : Someone who identifies outside of the gender binary of male or female, referred to as non-binary

Below is taken from NPR’s ‘A Guide to Understanding Gender Identity Terms’

Sex refers to a person’s biological status and is typically assigned at birth, usually on the basis of external anatomy. Sex is typically categorized as male, female or intersex.

Gender is often defined as a social construct of norms, behaviours and roles that varies between societies and over time. Gender is often categorized as male, female or nonbinary.

Gender identity is one’s own internal sense of self and their gender, whether that is man, woman, neither or both. Unlike gender expression, gender identity is not outwardly visible to others.

For most people, gender identity aligns with the sex assigned at birth, the American Psychological Association notes. For transgender people, gender identity differs in varying degrees from the sex assigned at birth.

Gender expression is how a person presents gender outwardly, through behaviour, clothing, voice or other perceived characteristics. Society identifies these cues as masculine or feminine, although what is considered masculine or feminine changes over time and varies by culture.

Cisgender, or simply cis, is an adjective that describes a person whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Transgender, or simply trans, is an adjective used to describe someone whose gender identity differs from the sex assigned at birth. A transgender man, for example, is someone who was listed as female at birth but whose gender identity is male.

Cisgender and transgender have their origins in Latin-derived prefixes of “cis” and “trans” — cis, meaning “on this side of” and trans, meaning “across from” or “on the other side of.” Both adjectives are used to describe experiences of someone’s gender identity.

Nonbinary is a term that can be used by people who do not describe themselves or their genders as fitting into the categories of man or woman. A range of terms are used to refer to these experiences; nonbinary and genderqueer are among the terms that are sometimes used.

Agender is an adjective that can describe a person who does not identify as any gender.

Gender-expansive is an adjective that can describe someone with a more flexible gender identity than might be associated with a typical gender binary.

Gender transition is a process a person may take to bring themselves and/or their bodies into alignment with their gender identity. It’s not just one step. Transitioning can include any, none or all of the following: telling one’s friends, family and co-workers; changing one’s name and pronouns; updating legal documents; medical interventions such as hormone therapy; or surgical intervention, often called gender confirmation surgery.

Gender dysphoria refers to psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity. Not all trans people experience dysphoria, and those who do may experience it at varying levels of intensity.

Sexual orientation refers to the enduring physical, romantic and/or emotional attraction to members of the same and/or other genders, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and straight orientations.

People don’t need to have had specific sexual experiences to know their own sexual orientation. They need not have had any sexual experience at all. They need not be in a relationship, dating or partnered with anyone for their sexual orientation to be validated. For example, if a bisexual woman is partnered with a man, that does not mean she is not still bisexual.

Sexual orientation is separate from gender identity. As GLAAD notes, “Transgender people may be straight, lesbian, gay, bisexual or queer. For example, a person who transitions from male to female and is attracted solely to men would typically identify as a straight woman. A person who transitions from female to male and is attracted solely to men would typically identify as a gay man.”

Intersex is an umbrella term used to describe people with differences in reproductive anatomy, chromosomes or hormones that don’t fit typical definitions of male and female.

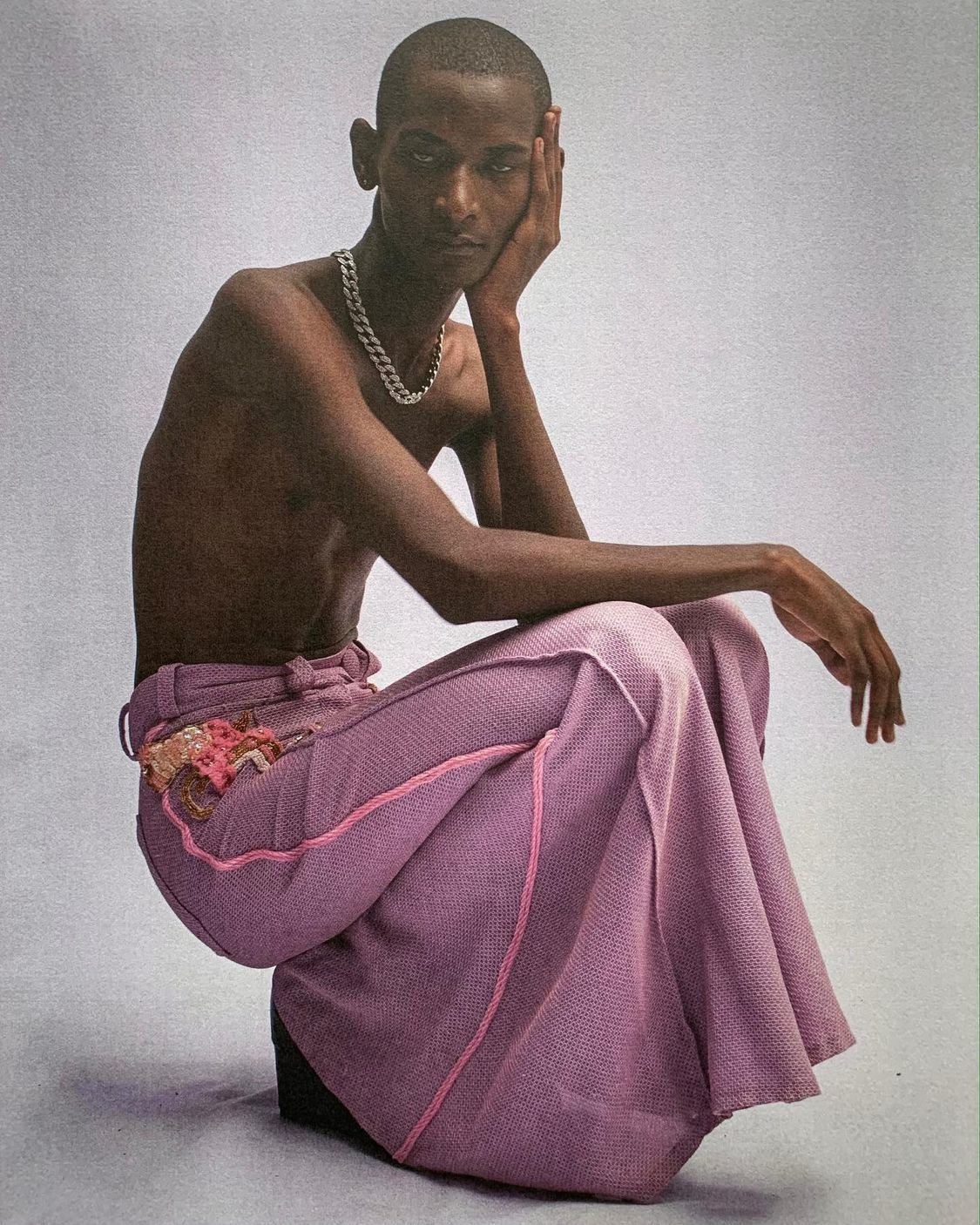

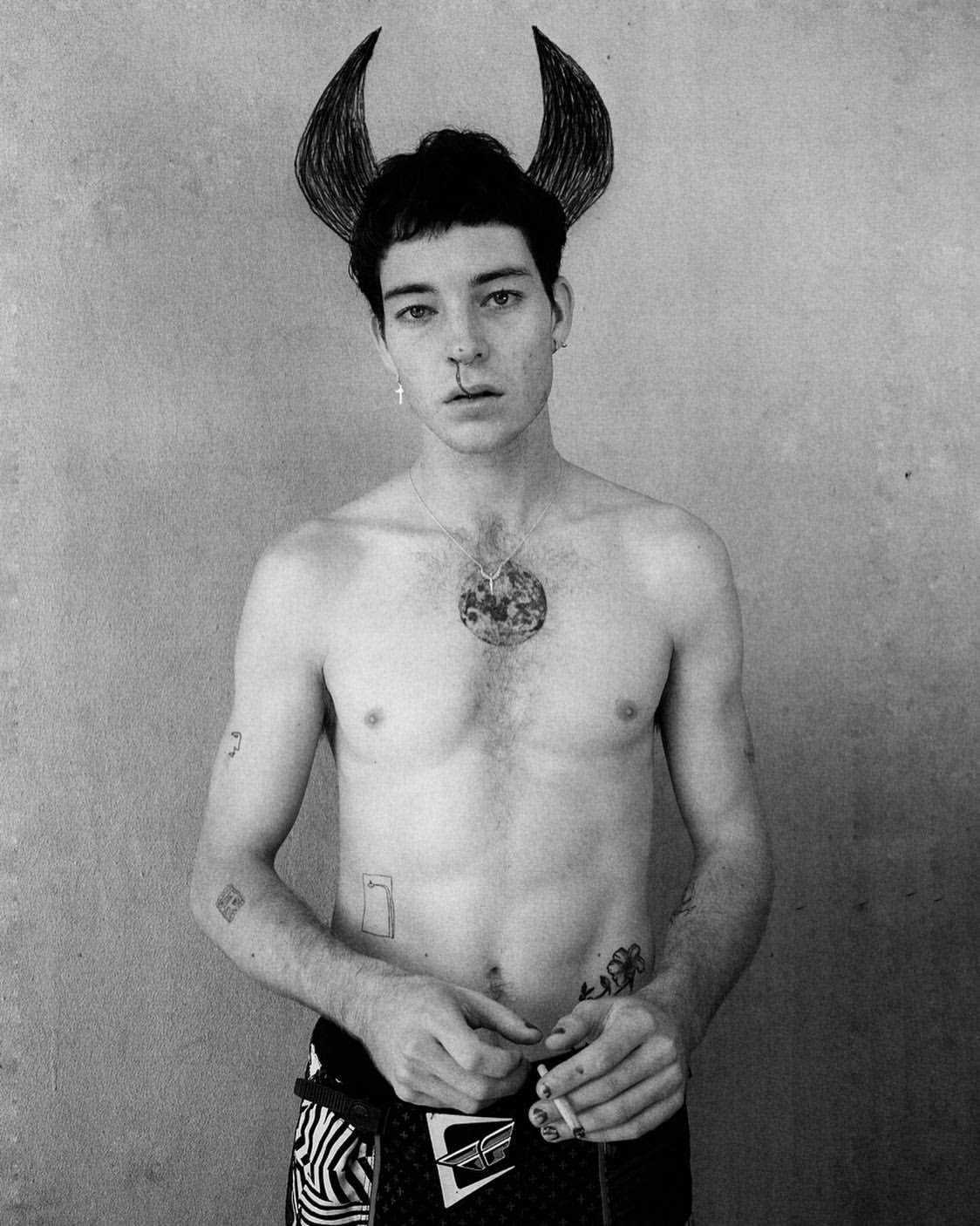

Model: Raphael Blue

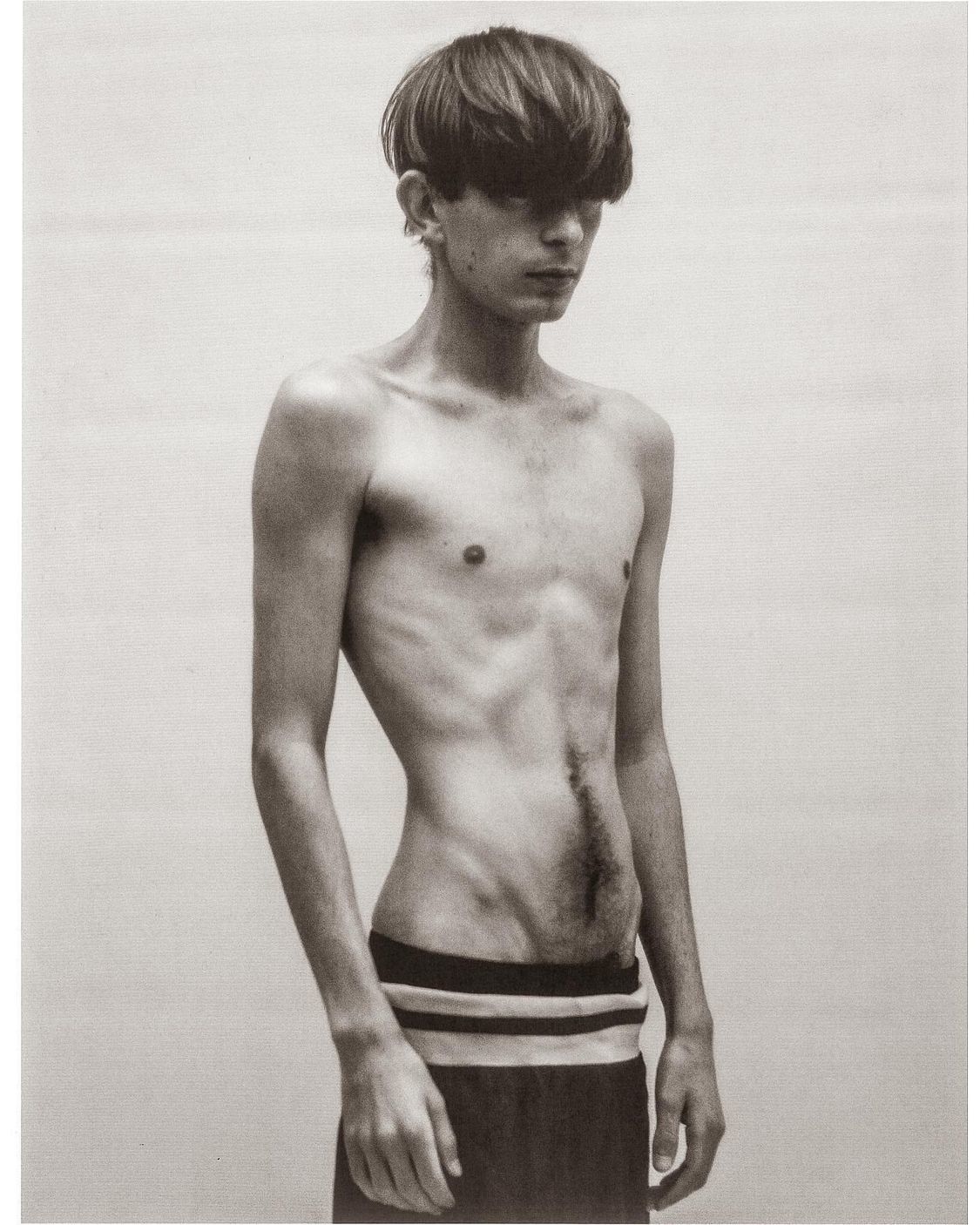

Model: Jeremy Pelser (self-portrait)

All images by Jeremy Pelser.

Written by: Casey Delport

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za