Our wardrobes are representative of our psyches, and fashion is as much indicative of our emotional and psychological terrain as it is about clothing our bodies for functionality. This I know to be true; as someone who has always ‘loved’ fashion, and who has straddled the finicky line between having certain instincts for my personal style set against struggles toward any kind of accurate or healthy self-perception, especially around how I wish to be perceived. In my early to mid-twenties, my sense of personal style had to be – as the kids say – ‘extra’, and in almost all instances where I knew I was going to be perceived for my sartorial choices, I had to signal my affinity for the obscure and unexpected, every single time. I simply could not allow anyone, least not myself, to perceive me as ever taking the road most travelled. God forbid, I didn’t make a statement.

A skirt over pants, a myriad of clashing textures – a chain hanging from my nose ring to my ear – chunky Dr Martens, bras over shirts, my poor but relentless attempts at upcycling, layers and layers and then some. In hindsight, my clothing choices served as emblems of my psyche then: non-conformist and deeply suspicious of authority, murky in my ability to make choices, and irreverent for a time in my life (teenhood) that was chaotic and uncontained. Equally, my clothing choices also expressed my penchant for joy and humour. Now, this is not to say that anyone who dresses with reckless abandon is necessarily expressing these ideas (I would never judge anyone, and in fact, I think maximalism is equally a healthy indicator of someone’s creative freedom or emotional exuberance) — instead, these are the conclusions I can examine, in retrospect, for myself today. I think examining our personal style choices is less about establishing a moral hierarchy and more about tracing the existential threads that bind us to the expression of our identities; and it’s an analysis worth undertaking, especially as we each navigate a world that demands our material allegiance to hyper-consumption; bloated shopping carts, fleeting trends and all.

We all have clothes in our wardrobe that seem to be waiting for the version of ourselves that we haven’t quite stepped into yet; or maybe never will. The emotional weight and psychology of fashion as self-promise and styling can become either a form of self-actualisation or avoidance; and again, personal style is an arduous journey; the question is, how deeply should we be curating ourselves, or can we just live on with reckless abandon, changing our style from moment to moment and day-to-day?

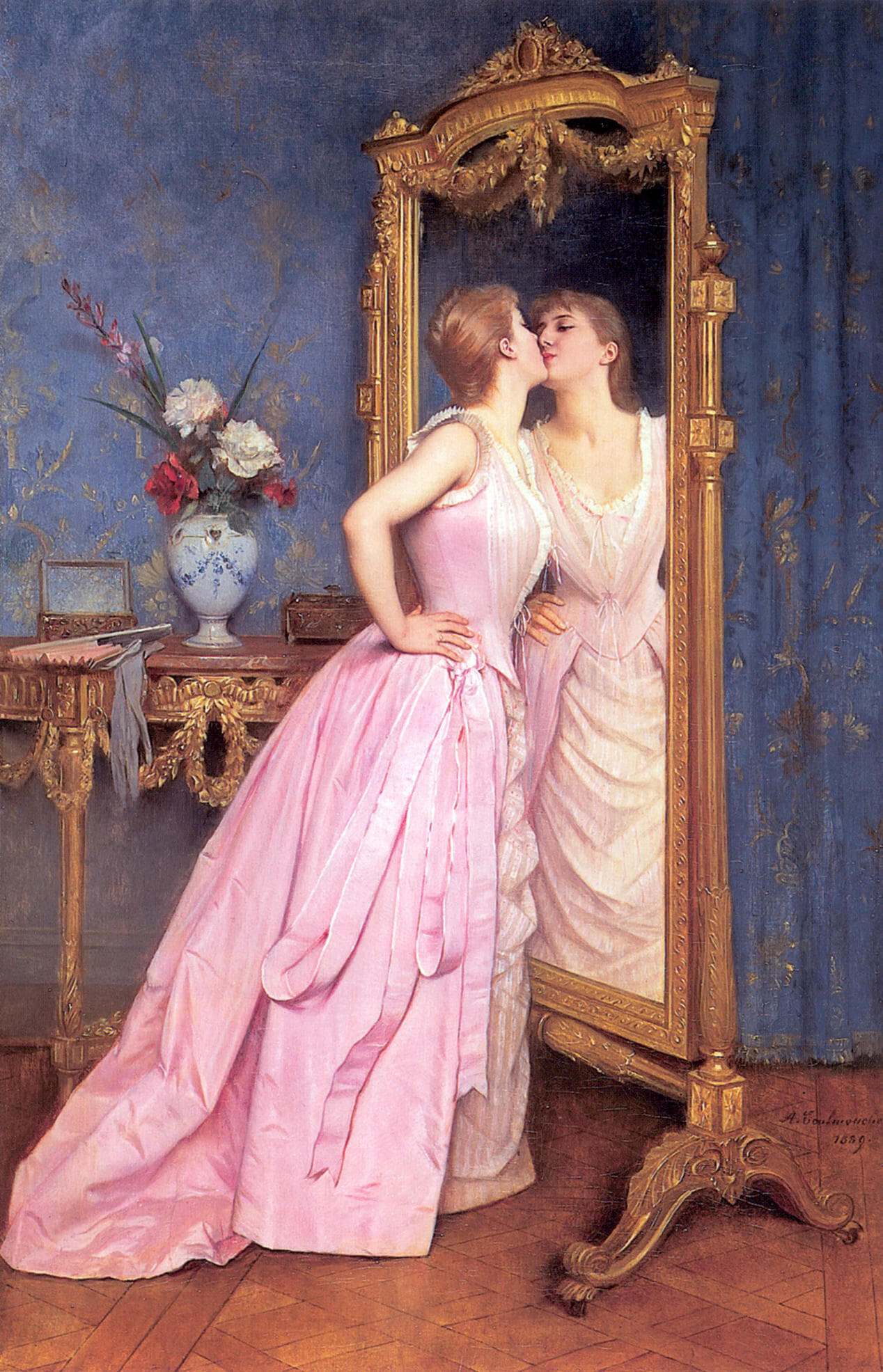

The wardrobe as a space is rarely neutral. It is, in many ways, an archive of the selves we’ve performed, abandoned, or longed to become. In Jungian terms, our clothing serves as a kind of persona; the mask we wear to interact with the world, shaped by the roles we feel we must play. We dress, consciously or not, to signal belonging, to conceal insecurity, to assert identity, or to protect our vulnerability. The outfits we choose become a tool of translation from our inner selves to the outer world, and it’s precisely this that makes fashion as a construct so endlessly compelling, and as a commercial endeavour; so wildly successful as an enterprise. The most powerful thing that you can sell someone, is their sense of self.

Fashion psychologist Dr. Carolyn Mair points out the self-regulatory function of fashion as it relates to human behaviour, writing in The Psychology of Fashion that, “what we wear affects how we feel, think and behave, and how others respond to us. Clothing is a powerful form of self-expression which can enhance self-esteem, improve confidence, and influence our psychological processes.” If dressing is a form of identity construction, then there is surely an ache that emerges when our wardrobe becomes populated by versions of ourselves we haven’t quite lived into, such as the dress that never made it out of the house; the boots we bought with confidence we didn’t yet possess, and for many of us, the pieces we bought that we might be one day be ‘thin enough’ to wear with comfortable confidence.

These items can gather dust on our shelves as echoes of imagined selves and in their silence, and staring back at them, they might ask us: who are you dressing for? Is it the present self, the aspirational self, or someone else entirely? This tension between authenticity and aspiration, between now and not-yet, can become one of the most emotionally complex aspects of personal style, and the promise fashion makes to us that we can somehow adorn ourselves to finally feel and be enough.

Aspirational fashion walks a fine line between transformation and illusion. On one hand, it can be a powerful tool for self-actualisation, as touted by the theory of enclothed cognition, coined by Hajo Adam and Adam Galinsky, which suggests that the clothes we wear actively shape our own thoughts, emotions, and behaviours. The researchers undertook studies centred around white lab coats to explore how clothing influences cognitive performance, and asked whether simply wearing a garment associated with a particular role — in this case, a doctor’s coat — could affect the wearer’s psychological processes. In one study, participants who wore what they were told was a doctor’s coat performed significantly better on attention-related tasks than those who wore the same coat but were told it was a painter’s smock, or who didn’t wear a coat at all. The researchers concluded that both the symbolic meaning of the garment and the physical act of wearing it had an impact on the wearer’s attention and cognitive control, and this suggests that our psychological understanding of our clothing is intimately activated through our perception. Thus, knowing why we wear something might yield results in ways previously unknown to our unconscious indifference. Clothing holds power.

Dressing like the version of ourselves we want to become can enhance confidence, cognitive performance. It’s why, working from home, I wake up and dress up each morning and I swear, it gives me the focus I need to separate my personal and professional life.

Again, I don’t think we need to be morally prescriptive here, instead, can we hold space for a more nuanced awareness? When those future versions of ourselves don’t arrive, or when life doesn’t align with the image we’ve dressed for, what remains? Are we holding onto garments that once felt aspirational but now hang heavy as emotional clutter? Is it actually even really that deep?

Across social media, personal style has become a kind of visual shorthand for identity that is curated and easily recognisable. The rise of the “signature style” and the capsule wardrobe movement reflects a broader cultural desire for coherence and control, and perhaps a tightly edited wardrobe of neutral tones has come to signal discipline and a sense of self that doesn’t waver. I think of my earlier style — more experimental, eclectic — and compare it to my current affinity for ‘less is more’. Still, I find myself wondering: is this shift actually an expression of a hard-won inner clarity? Or am I, like, selling-out? The beautiful thing is, though, that personal style is a life-long process; it’s present with us in all the seasons of our experience.

Similarly, such rigid consistency across how we dress can risk reducing style to performance rather than expression. In contrast, bell hooks wrote passionately about clothing as a space of liberation, particularly for Black women, whose identities have long been policed and politicised. In her work, clothing was intellectually and politically relevant as a site of resistance, creativity, and truth-telling, and bell championed the right to dress in ways that reflect multiplicity over any kind of conformity or strategic legitimacy. This is truly personal, sartorial freedom.

When we shift our look daily, monthly or weekly are we actually just simply being honest? Perhaps dressing differently each day is a reflection of the many selves we hold within, and maybe that’s the whole damn point; that seizing the mood of the moment, as we change with nuanced effect each day, is an act of self-respect. I suppose if there’s one noble thing fashion can do, it’s to remind us that none of us are fixed or unoriginal; our clothes are simply one small part of the entire complexity of who we are.

I guess, I’ll stay layering; my recklessness charged toward self-acceptance.

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za