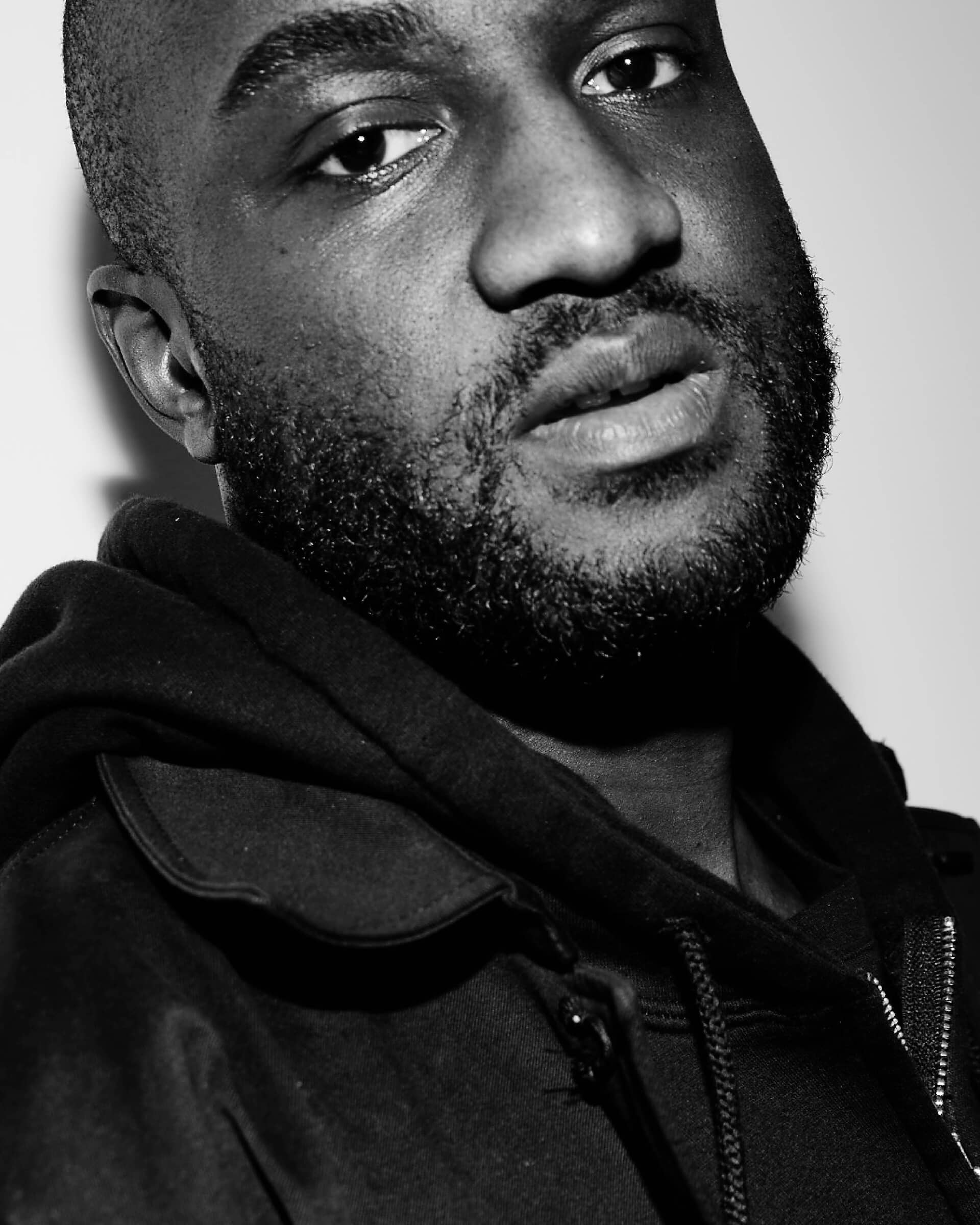

Now, with a body of work that suffuses technical precision with poetic instinct, it’s almost surreal to imagine that her earliest forays behind the camera included muses like Isabel Marant, or that she was present during the golden days of Self Service, on the cusp of Bella Hadid’s ascent, or in the thick of it at a Supreme party alongside Virgil Abloh and Tremaine Emory. Katinka’s testing ground was the fashion frontier — and most refreshing about her is the way she views those mid 2010s experiences: as fun, irreverent, and ultimately inconsequential to her sense of self or creative purpose. As Katinka later tells me, “I’ve always had a good head on my shoulders.”

What’s the opposite of clout-chasing, as the kids call it today? Of myth-making? This refusal to pedestalise the hype is perhaps Katinka’s most fundamental quality professionally (aside from her phenomenal talent) — a grounded relationship to reality, to fame and to the fleeting nature of it all. That a 22-year-old South African bartender from Cape Town’s iconic P&G’s could end up shooting backstage at Paris Fashion Week or brushing past Chloë Sevigny at a Supreme party, is a reminder that talent, spirit, and an openness to possibility might be the best passport of all; these are the substances of instinct, timing, and a kind of creative courage that can be neither taught nor bought.

This sense of spontaneity — of letting life unfold in wild, unscripted ways — is something Katinka has carried since her days behind the bar at Power & Glory, part of the bar’s initial set of bartenders who shepherded its glory days; “It was wild — we had no rules, played our own music, threw people out if we didn’t like them,” Katinka laughs. “It was a creative hub, really. All these incredible people passed through, even international celebrities when they came to shoot films. That time really confirmed for me how much I love working with people, and that I thrive in chaotic environments.”

Starting as a ‘digi’ on sets — a digital assistant – and quickly known for her speed and precision, Katinka’s work alongside photographers and clients was edified in frenetic environments. Ulrich Knoblauch, one of South Africa’s most revered fashion photographers, became her mentor and gateway to the wider world of New York and Paris fashion. “I honestly owe so much to him — he believed in me, pushed me, and brought me into international space.”

Katinka’s entry into the world of fashion was anything but conventional; “Ulrich started shooting the First Looks for Self Service Magazine, it’s this intense backstage moment before models step onto the runway,” she explains. “You don’t know if you’re going to get your shot. Designers can be cutthroat, they can be yelling ‘Vogue can stay, Interview can stay, everyone else — out,’ It was wild. Ulrich got headhunted to do other work and eventually brought me in. I bought a ticket to New York and just went for it.” Self Service is something of a myth today, and the bi-annual Parisian publication is perhaps the last stop on the road that winds out of fashion’s print publishing heyday. Katinka’s approach in those early days was unapologetically gutsy, and she recalls barreling late into an Alexander Wang show, weaving under legs and demanding space in the ‘pit’ (the chaotic frontline for photographers at shows). Yet, as Katinka notes, her photographs reveal none of the frenzied battle behind the scenes and that, “I’ve always been instinctive. When you’re working backstage, there’s no time to curate — you shoot fast, and you shoot with feeling,” she says. “That kind of working environment taught me to trust my eye and my body, to shoot from intuition rather than overthinking. It’s become part of my style. I know how to get the shots I want.” There can be this perception that the best artists or creatives are those who endlessly deliberate and rework every frame; thousands of shots later, and exhausted time spent. I have always been suspicious of this kind of methodical obsession, and whether it has little bearing on true skill or talent; often, it feels typically self-indulgent. Rather, Katinka’s ability to carve the precise image she wants out of imperfect circumstances or compositions renders her work radically and totally free from artifice and constraint. Sensational.

What began as assisting soon morphed into a solo practice, as designers began requesting Katinka directly; “That’s how I started shooting house shows; when a designer hires you to shoot their backstage privately. I worked with Isabel Marant, Lemaire… I remember sitting at the table with Christophe Lemaire, thinking: ‘What is my life?’ I was a 22-year-old South African girl — and I was somehow part of this world.”

“She was this incredible presence — always a glass of champagne and a rollie in hand,” Katinka says of Isabel Marant, who I feel is truly one of the most chic women to have ever existed. “There was this moment after one of her shows where we locked eyes and I just knew — she was saying, ‘I see you.’ There was a kind of unspoken respect between us as women, across very different worlds.” That mutual respect extended into creative trust, “when Isabel asked me to shoot her party in a Studio 54 kind of way, I said yes — but on one condition,” Katinka notes, of the cheeky hubris often only afforded to us by youth, “I told her I needed my own barman and champagne on tap, because the only way to really capture that energy was to become one with the crowd,” Katinka grins. “It worked! I got the shots, and I had the most fun doing it.”

Continuing the lore, which has me in a grip, Katinka notes with a shrug, that “I crashed Vogue’s 100-year party in Paris,” as if it’s the most casual thing in the world. “Ulrich told me, ‘You’re Katinka, you can get in anywhere.’ I didn’t have an invite, but I was standing there with Self Service in my hand, looking the part. The bouncer let me through and gave me a VIP wristband — later I found out they can get fired if they don’t recognise someone important enough. So he must’ve thought I was someone famous! Next thing I know, I’m in VIP with Lenny Kravitz, drinking Veuve from stemless glasses and dodging oversized joints. It was insane.”

Now based in Cape Town, Katinka finds herself at a creative crossroads, balancing the weight of experience with a longing to return to instinct. “The industry today feels… difficult,” she says, candid as ever, as I’m learning Katinka’s disposition is a full expression of refreshing honesty. “There are so many platforms, so many expectations, and so little time for real craft. Sometimes I feel like I’m drifting away from the reason I started shooting in the first place. I’m trying to find my way back.”

If Katinka’s early career was built in the chaos of backstage fashion and global runways, her current work emerges from a deeper place; rooted in trust, intimacy, and a fierce devotion to the inner life of her subjects. “My work is a poetic dance to me, and I’m always interested in playing with light, colour, and, most importantly, my subject,” she explains. “Empowerment has always been a huge thread running through everything I do. For me, the process is actually more important than the final image itself.”

That emphasis on process is what sets Katinka apart, and it is the felt experience when viewing her images; “over the years, I’ve worked with so many people, sometimes those experiencing a photo shoot for the very first time. I approach each session with care, trying to gently uncover and decondition them — to help them find their own power. It’s a kind of beautiful psychology that I absolutely love being part of.” Ironically, for someone so adept at making others feel seen, Katinka finds visibility unnerving. “I’m probably a bit hypocritical because I’m actually terrified of the camera myself,” Katinka admits. “Interviews terrify me. But I have this enormous respect for the bravery it takes for people to show themselves in that way — to be vulnerable and open. For me, patience is key. I try to show my subjects how truly beautiful they are, even when they can’t see it yet.” It’s no small thing holding space for someone to reveal themselves. Whether through a lens or a conversation, it’s an intimate job and over the years, I’ve come to recognise it as my most essential purpose when interviewing: to create a space for someone’s truth to surface; unforced and entirely their own.

That mutuality is central to Katinka’s practice — a resistance to the industry’s more extractive tendencies. “Something I always keep front of mind is that whoever I’m shooting, it’s a mutual assembly of expression. My subjects are never objectified. That’s hugely important to me. In our industry, I think that’s often missed,” Katinka says. “To get the best out of someone, you have to attune to their needs — not expect them to conform to yours. That’s a big misconception that I see a lot.” Even in Katinka’s personal projects, nothing is fixed. “I never really know how an image is going to come out,” she says. “I might have an outline, but I almost never stick to it rigidly because the shoot is always a mutual creation. It’s that openness and shared expression that makes the work so meaningful.”

While people remain her favourite subject, Katinka’s gaze is also always toward land, light, and the strange and beautiful world of nature. “I reference paintings a lot, and often try to see landscapes in an abstract way. I notice shapes, light, and the animals that seem to emerge from those forms,” Katinka explains. “As a typical Cancerian, I find emotional depth in nature — it’s where I often go when I’m feeling low or depressed. For me, photographs are the way I give back my inner world.” Cancerians are the zodiac sign known for an almost permanent immersion in the watery depths of the emotional body, intuition and nostalgia; glancing through Katinka’s work, this foundation is entirely traceable throughout.

I ask Katinka whether she’s always had an eye for seeing what others might not be able? “I think I’ve always had an eye for it,” she responds, “Even as a child, I used to comment on the world around me — the surroundings, the details. That sensitivity has stayed with me and continues to shape how I see and capture the world.” Katinka is an intermediary between moments that existed and those of us who were not there or couldn’t see it; as I’ve said before, there is something shamanic when photographers are able to collapse time and reveal presence. This is witch-work, baby.

Right now, Katinka is on a break and involved in personal projects as she confronts the existential crisis that commercial work has stirred in her. As an antidote, she began offering her services free of charge to local brands — with the only prerequisite being that she could be conceptually involved. This act of service can be wholly transformative for a brand. As Katinka muses, “Photography is expensive — I would know!” — adding that these collaborations have led to some of the most gratifying work she’s done in recent years.

Then there’s the recent shoot she did with stylist Liza Lombard, one I’ve been returning to on a near-daily basis to fawn over. While Katinka might be feeling jaded in some ways, I suspect she’s at the threshold of being in her element; and as her life has demonstrated, she will know where she needs to be, and what she needs to do. As is customary for CEC, I ask Katinka for her words of wisdom; “the most vital thing is to trust your own artistic voice,” she says. “We all draw inspiration from others and we all love to reference, and that’s important — but your personal reference, that inner voice, is your creative identity. That’s what sets you apart.” Katinka is also a firm believer in mentorship and acts of service. “Keep teaching. Keep inspiring. If someone reaches out to you, take the time to respond. It’s your responsibility to share what you know and help build the community. No one else can replicate your image — not exactly, not fully — even if it’s of the same subject, so don’t guard your creativity. Generosity is part of growth.”

I know that I can be flippant with my use of the word ‘iconic’, but in this context, it couldn’t be more apt or true; Katinka Bester is iconic, in every sense of the world – may we all be as comfortable in the mountains as we are backstage (or in the thick of our places of chaos), and may our inner dualities always guide as to build our most exceptional and beautiful lives.

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za