Fashion is rarely born in a vacuum; instead, it loops back to other places, other bodies, and other times. Acknowledging that almost every silhouette, textile, or stitch tells a story that’s been told before, in part, is not a failure of originality but a feature of the form. Fashion, like language, is built on memory, and it is shaped by cultural lineage and personal nostalgia, collective dreams and historical trauma. In this way, garments are layered expressions that leverage technical materiality to pursue the past, as it bleeds into the present.

To understand this, we need to talk about referencing; and this is precisely what this ‘fashion nerd’ edition of Interlude entails. Can you believe it’s been 40 Chapters? I certainly can’t. In design, “referencing” is not a dirty word – it’s a form of communication, and a way of positioning oneself in relation to what has come before. From Margiela’s ghosts to Thebe Magugu’s storytelling textiles, the act of citing or sampling a past idea is deliberate and profound, and to me, it’s what makes fashion an art-form rather than merely a commercial pursuit.

A fashion reference is a deliberate nod to something pre-existing – a garment, silhouette, motif, designer, era, or cultural moment. It can take the form of direct citation (a near replica), loose inspiration (a mood or aesthetic), or abstract sampling (a deconstructed trace). Referencing, citation, and sampling function much like they do in music, literature, or art. Think of how a track might loop a sample from an old soul record, or how a filmmaker might mimic their favourite director’s signature camera angles; such gestures are a signal: ‘I’ve seen this before, and I’m showing it to you again, through my eyes.’ Equally, they speak to the creators own reservoir of cultural curiosity; the things they have amassed, personally, to inform their work.

Black Hat Bandits for Thebe Magugu’s SS22’s DOUBLETHINK Menswear project, photographed by Kristin-Lee Moolman and Styled by Chloe Andrea Welgemoed, via @thebemagugu IG

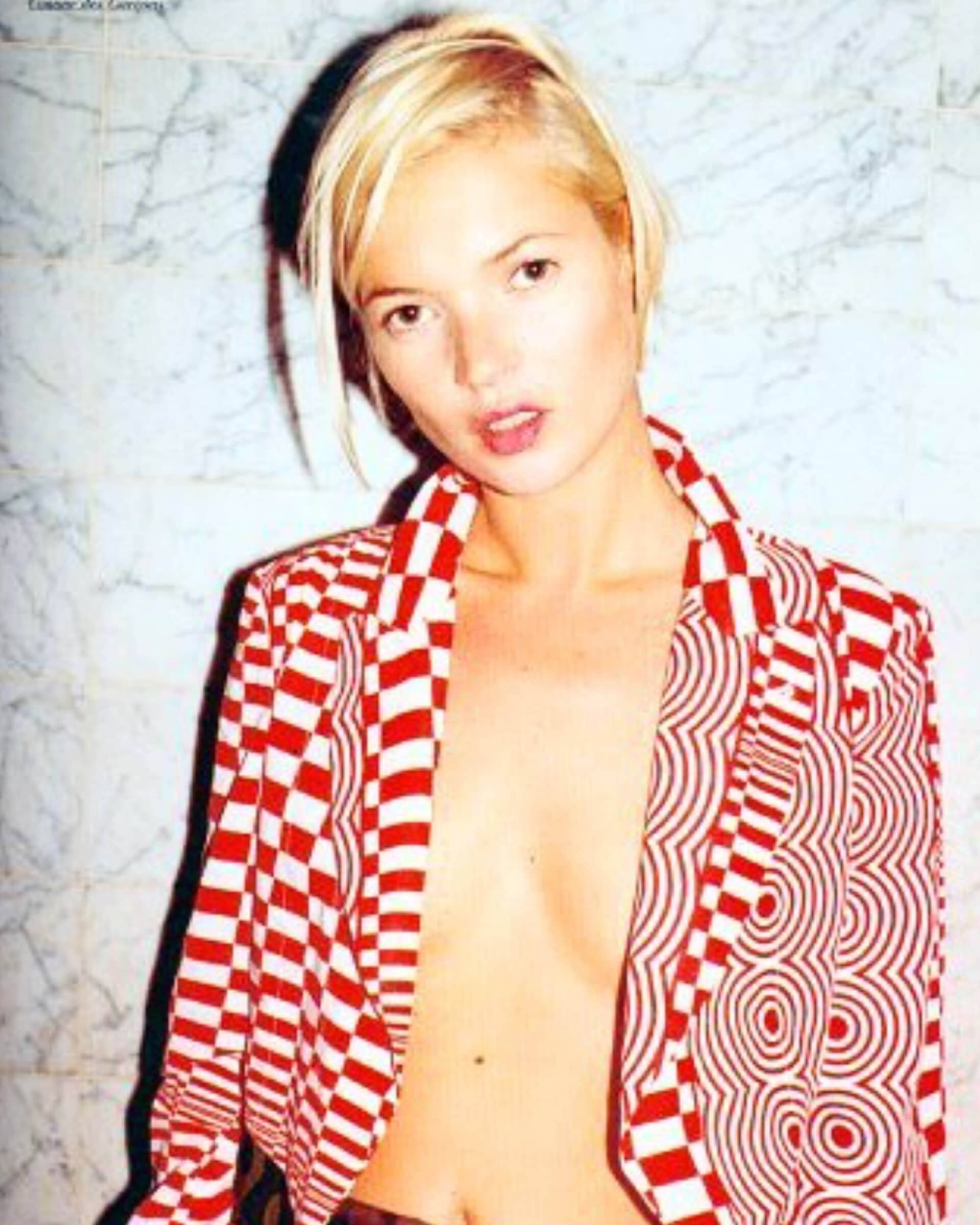

Kate Moss for Comme des Garçons, photographed by Juergen Teller, via @commedesgarcons_archives IG

Importantly, referencing is not the same as copying. Whereas copying is mindless mimicry (hello, Shein…), referencing is contextual and intentional. It asks: what does this thing mean now, in this time, through this lens? At its best, referencing introduces a past idea into a new conversation, allowing it to evolve. It also speaks to a broader cultural condition, as fashion is a collective aesthetic vocabulary – built over time, across borders, and through our shared memory. In this sense, every designer is in dialogue with an archive, whether consciously or not. Referencing makes that dialogue visible, and gives us the tools to read fashion as the designer’s attempt to make-meaning and tell stories.

To train your eye for fashion references is important ; the more you look, the more that you see where it’s coming from. Silhouettes are a good place to start; is there a wasp-waist and full skirt reminiscent of Dior’s New Look? A boxy, oversized jacket nodding to 80s power dressing? Look at fabrics – is that raw denim a callback to Japanese and Americana workwear traditions? Then there are styling cues: socks with heels (a Prada classic), exposed seams (a Margiela signature), or even hair and makeup that recall a particular decade or subculture (Pat McGrath, we see you!). To truly see these cues is to become fluent in fashion’s grammar and over time, your eye and language sharpens.

South Africa’s most cerebral and referentially fluent designer, Thebe Magugu, references the past with a specific kind of urgency. The archive is immense, so I’ll only make mention of a few. In his SS21 collection Counter Intelligence, Magugu engaged his work with political memory; drawing from interviews with female apartheid-era spies and the confessional accounts found in Jonathan Ancer’s book Betrayal – The Secret Life Of Apartheid Spies. The collection treated clothing as both documentation and disguise, and these references recontextualised through the lens of South Africa’s complex history, offering fashion as both archive and interrogation. Magugu’s work shows that referencing can function as a mechanism of truth-telling, especially in postcolonial contexts.

In Home Economics and African Studies, Thebe again turns personal and political memory into design. The angel-sleeved neoprene dress, printed with an image of women clinging to one another, is a cry against South Africa’s quiet but persistent war on women. Here, referencing becomes a way to critique cultural expectation and reclaim agency, pulling from everything from household imagery to domestic textiles. In African Studies, Magugu references childhood motifs and matriarchal habits as a way to claim a deeper authorship of African identity. These designs push back against the extractive gaze of Western fashion systems, offering instead an intimate, self-determined portrayal of what Africa looks and feels like when rendered by someone who lives it. This level of referencing, intersectional and deeply political, has exalted Thebe Magugu to the level of a cultural historian and sartorial theorist.

At Dior, JW Anderson’s recent menswear debut was thick with layered references; some national, others archival. It is a terribly rattling thing to step into a house as storied as Dior, and be expected to both offer something new and entirely one’s own; while respecting the legacy of the house itself. One of the most poignant signs that Anderson is finding his feet, firmly so, was his use of Irish Donegal tweed to reinterpret the iconic Bar jacket, originally introduced by Christian Dior in 1947 as part of the “New Look.” The choice of fabric was for Anderson, an Irish designer, a personal tether to heritage, and his way of recoding Dior’s classic Parisian glamour through a lens of his own national pride. Elsewhere in the collection, those cargo shorts featured side-looped flanges directly inspired by the sculptural architecture of Dior’s 1948 “Delft” couture dress. These acts of homage filtered through Anderson’s signature play with volume and gender. In reimagining house codes with a distinctly off-centre eye, Anderson referenced the legacy of Dior’s sculptural femininity, queered and unfastened for a new generation – in this context, for men. This collection, overall, was a masterclass in working with the breadth and depth of house archives such as the references bursting from Dior; and making them entirely one’s own.

JW Anderson’s References Dior 1948 couture Delft Dress as Cargo Shorts, details via @jonathananderson IG

Martin Margiela SS97, via @oldmartinmargiela IG

Much can be said about Rei Kawakubo’s referencing; this is a whole space of study, to be honest. Rei Kawakubo’s Fall ’97 Adult Punk collection for Comme des Garçons took referencing into more chaotic terrain. Vogue described the models as “alien sprites” with mohawks and full theatrical makeup; while the collection played with decay and disorder, evoking a kind of deconstructed Victoriana — what Vogue memorably called “Miss Havisham’s couture atelier”, a referencing to the eerie Charrles Dickens character from ‘Great Expectations’. Underneath the aesthetic lay a deeper referencing mechanism: a challenge to the notion of coherence itself in fashion. The collection seems to be equal parts a nod to Victorian England and Japan’s Imperial age, all tempered by Kawakubo’s ability to ground her work in punk aesthetics. Kawakubo is one of the most preeminent leaders in citing punk as an attitude, and her unsettling designs were at the time interpreted as destructive. In this way, Kawakubo’s referencing is self-weaponised to say precisely what she wants to about fashion, beyond the societal discourse; often leaving viewers guessing about her true intentions.

Few designers are referenced as frequently – or as reverently – as Martin Margiela. You’ll be hard pressed to find a designer today who hasn’t, in some way, been inspired by Margiela’s work; long before there was Demna’s antagonist ‘enfants terrible’, there was Martin. In the 1990s, he rewrote the rules of fashion by deconstructing and upcycling before it was ever cool or even seen as interesting, and his influence continues to haunt runways today, especially in Japanese fashion, alongside designers like Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto who shared a similar appetites for abstraction and rebellion. They too referenced tradition (kimono shapes, ancient textiles) only to distort it. Together, this school of referencing rejects commercial glamour in favour of philosophical depth; ultimately, it’s referencing as a way to dismantle norms and reconstruct meaning from the ruins.

In contrast, Thebe Magugu continues to offer a deeply local and politically resonant approach to referencing. His collections draw from South Africa’s archives – familial histories, apartheid-era documents, traditional dress, and protest movements. Magugu’s referencing locates global fashion in specific South African narratives, challenging Eurocentric assumptions about who gets to be in the archive. In his hands, referencing has become a method of cultural preservation and a political act. I’d argue, too, that Thebe’s work poses a kind of transmutation or healing by centering the past as something integrated into our current, creative conversations.

Understanding fashion references sharpens your visual literacy, and it’s the difference between seeing a garment and reading it. Referencing teaches you how designers think and how they place themselves within a lineage, what they borrow, and how they build on it. For aspiring designers, this is crucial – albeit, exhausting to hone in on, I’d imagine; when life bears so much depth and complexity to draw from. Referencing helps one situate their work in context, and it shows that we are aware, intentional, and in conversation with history. For critics or consumers, it’s equally essential: it enables us to appreciate the depth behind a collection, to spot cultural references, and to interrogate questions of authorship and originality. Ultimately, it allows us to engender a deeper appreciation for fashion. Referencing, to me, is what makes fashion as interesting to think about, as it is to look at it.

Indeed, referencing also opens up ethical terrain. When is it homage, and when is it theft? How does one draw from another culture respectfully? These are not easy questions, but they are the right ones to ask. Take, for instance, Martin Margiela’s seeming monopoly on the Japanese Tabi. There’s a rhetoric today that Tabis not made by Margiela are somehow ‘dupes’—a notion that’s laughable when you remember the split-toe shoe has existed in Japan for centuries, long before the Maison ever elevated it to fashion’s avant-garde pedestal.

Ultimately, referencing is a way for designers to participate in fashion’s larger, ongoing story. That awareness is what gives those ideas resonance and strength, as fashion functions as a living archive: a record of who we have been and who we are in the process of becoming. When designers reference the past, they are translating it, bending it into new forms, inverting its meanings, and reinventing its possibilities. In doing so, they remind us that fashion is an ongoing dialogue that spans generations, geographies, and ideologies.

The next time you encounter a collection, it is worth looking a little closer. Instead of asking only what is new, can we consider what is being remembered, reinterpreted, or reasserted?

Written by Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za