If you have had the pleasure of coming across ASA SADAN’s IG feed – you will know their epitaph is “luxury.heritage.tradition.modernity” – and these four words encapsulate the conversation I am grateful to have had with the label’s founder, Imran Mohamed. This conversation is one of those times when I really wish this was a podcast; because conveying the depth of the threads we discussed in written almost feels reductive – but I hope, as always, that I will do it justice.

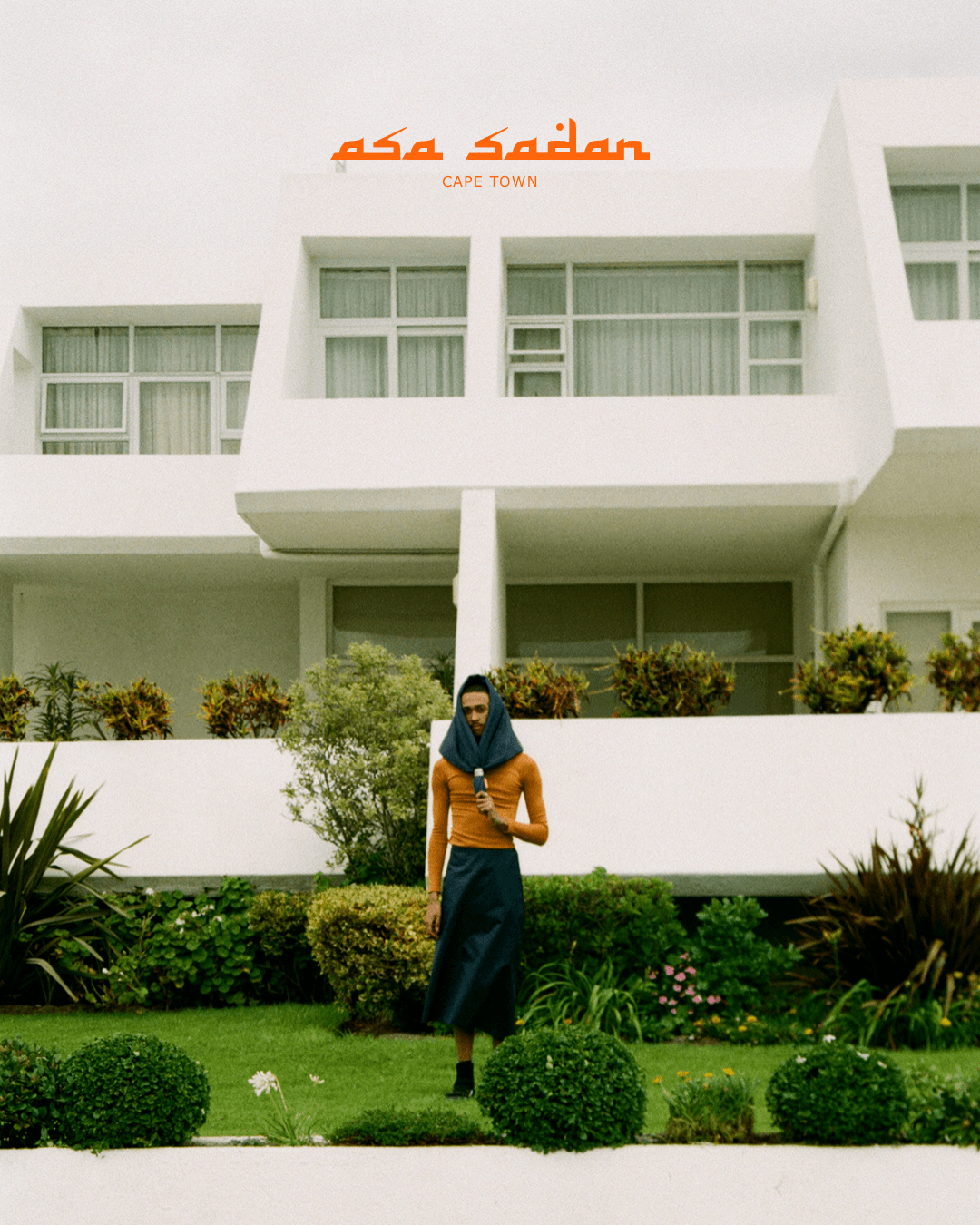

Imran is a fascinating creative director – in the truest sense of what that title has come to mean in fashion today. We tend to create this mystique around the role of a creative director – imagining somehow that it is this person entirely who cut, sew and dress the garments – that they act alone, mysteriously so. I have often wondered if this is not a symptom of individualistic thinking in the west; that in order for something to be profound, it has to have originated from the mind and hands of one person – that we cannot, possibly, acknowledge the very truth of our nature as human beings; an existence that is wholly dependent on one another, no matter how compartmentalized the society is in which we operate. A creative director, in the way that I consider it, is someone from where the vision originates – or is grasped and put forth into tangible motion. It is the person entrusted to lead and draw out from those around them the very best aspects, for the momentum of an entire viewpoint. When the citrus-hued arabic-style monogram of ASA SADAN popped up on my feed through Duck Duck Goose – I was thrilled. I briefly discussed ASA in chapter 01 of Interlude – in which I said, ASA SADAN makes the case for “why sartorial lineages between cultures and communities will always be the original blueprint for everything we might see on the runway or in windows.” I stand by this sentiment particularly in the context of Imran’s work, especially after our conversation.

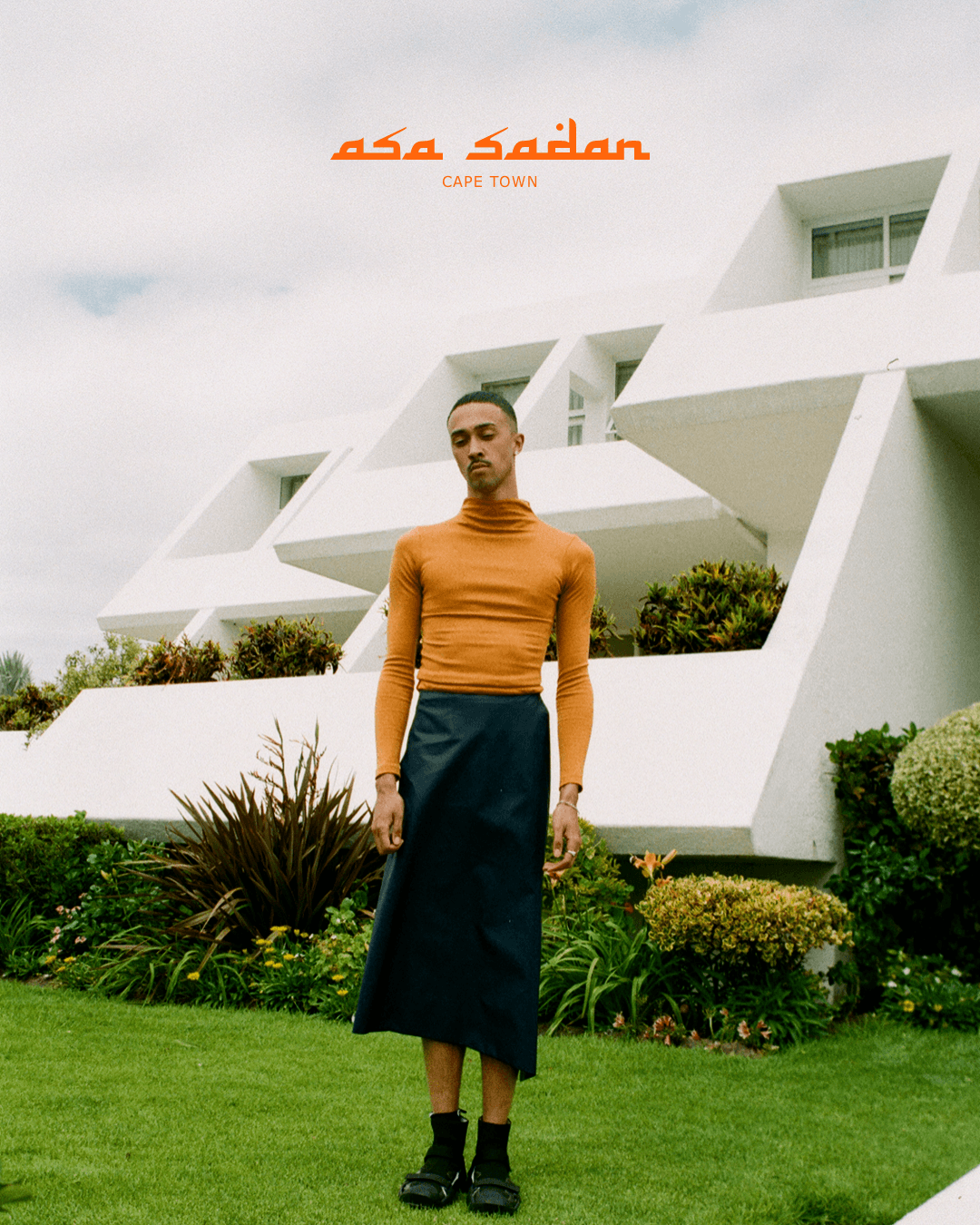

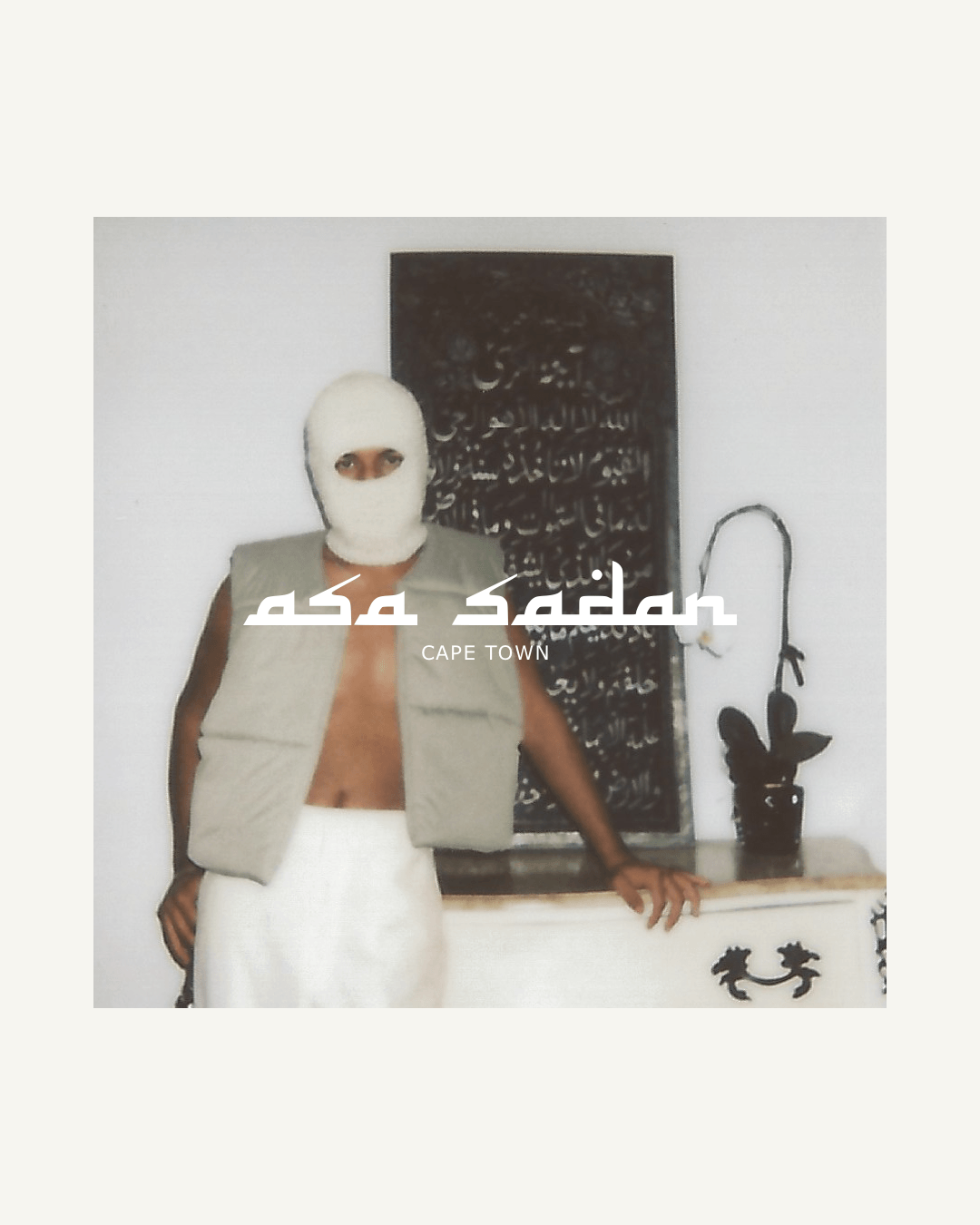

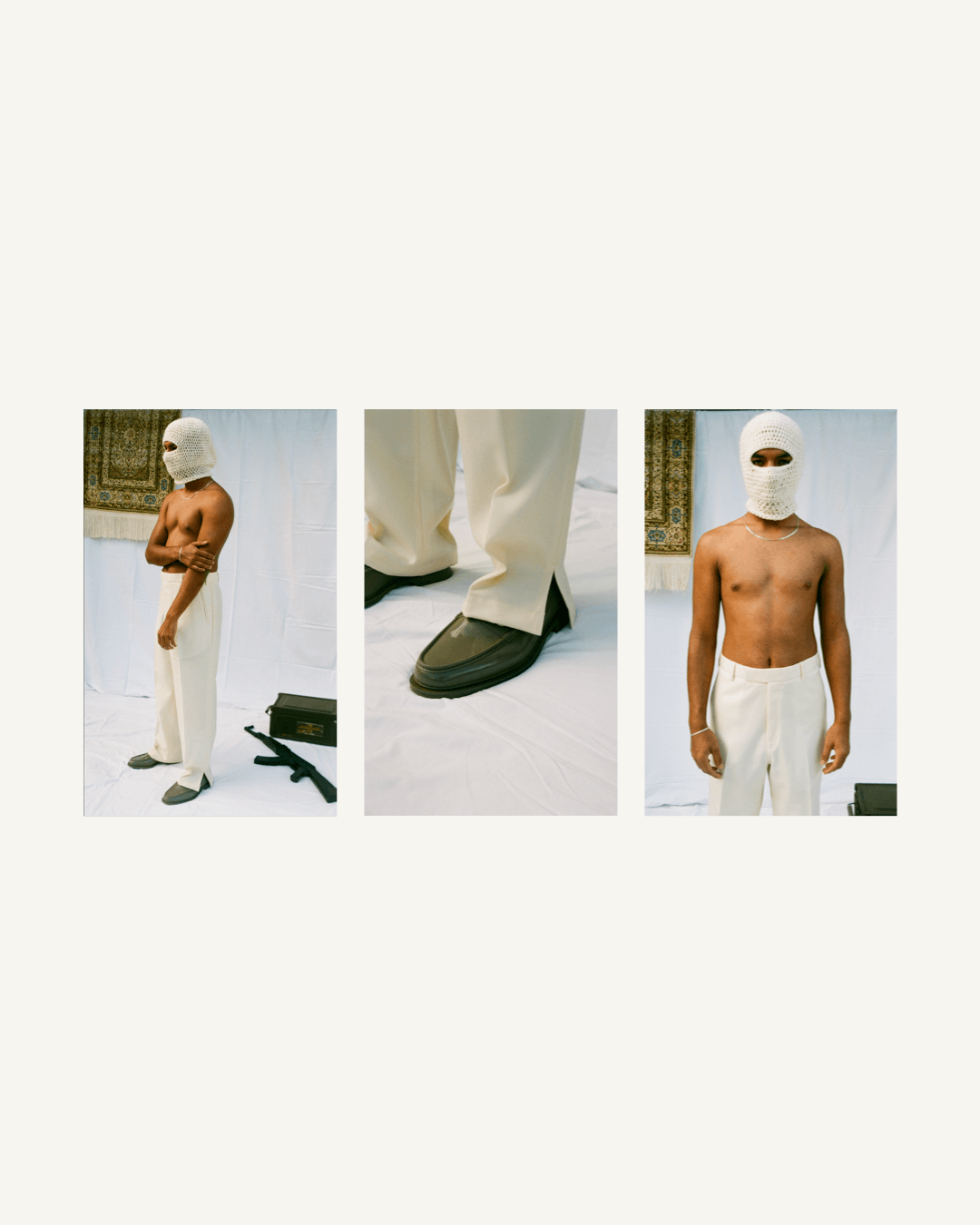

“I have always had an affinity for fashion and design – I was born into a family in which fashion was our bread and butter. My grandparents and mother and extended family were in the industry all in different roles – from managing factories, to my grandfather being a couturier and my mom had her own brand, and then became a senior brand for big retail groups in South Africa. My dad’s father moved from Joburg to Cape Town, I think in his forties, and reinvented his pathway – settling on men’s retail. He founded Skipper Bar, which brought trends and labels to South Africa during apartheid, where it was almost impossible to bring anything in. I think that time was around the 1970s/80s, when Grasshoppers came out locally, and internationally it was Lee Jeans.” Imran says, and the last line is a subtle gesture that makes me realize how deeply nostalgic fashion can be in Cape Town; its this juxtaposition of local heritage intermixed with global aesthetics; something which ASA SADAN has conveyed beautifully with the single pleat trouser – a nod to Cape Malay, Muslim tailors that are so embedded in the garment culture of the city – alongside the tech-wear tactical vest.

“After I finished my honours at UCT, beginning in engineering and then moving into real estate, I started to see all these disciplines and practices as truly being varying models of design. I think fashion is just another medium to convey one’s perspective on how to build products and re-shape systems, and for me it’s always for the benefit of people. My fashion journey in the industry began at Corner Store alongside Two-Bop, Sol Sol and Young&Lazy – working with I and I as an intern. That was still a time when I think a lot of other places were not willing to share their knowledge or contacts, so Corner Store was pretty pivotal in that way. Shukrie Joel, the owner of I and I, was my mentor for six months, and he comes from a tailoring background, so his different take to traditional streetwear that we were seeing at the time influenced me a lot.”

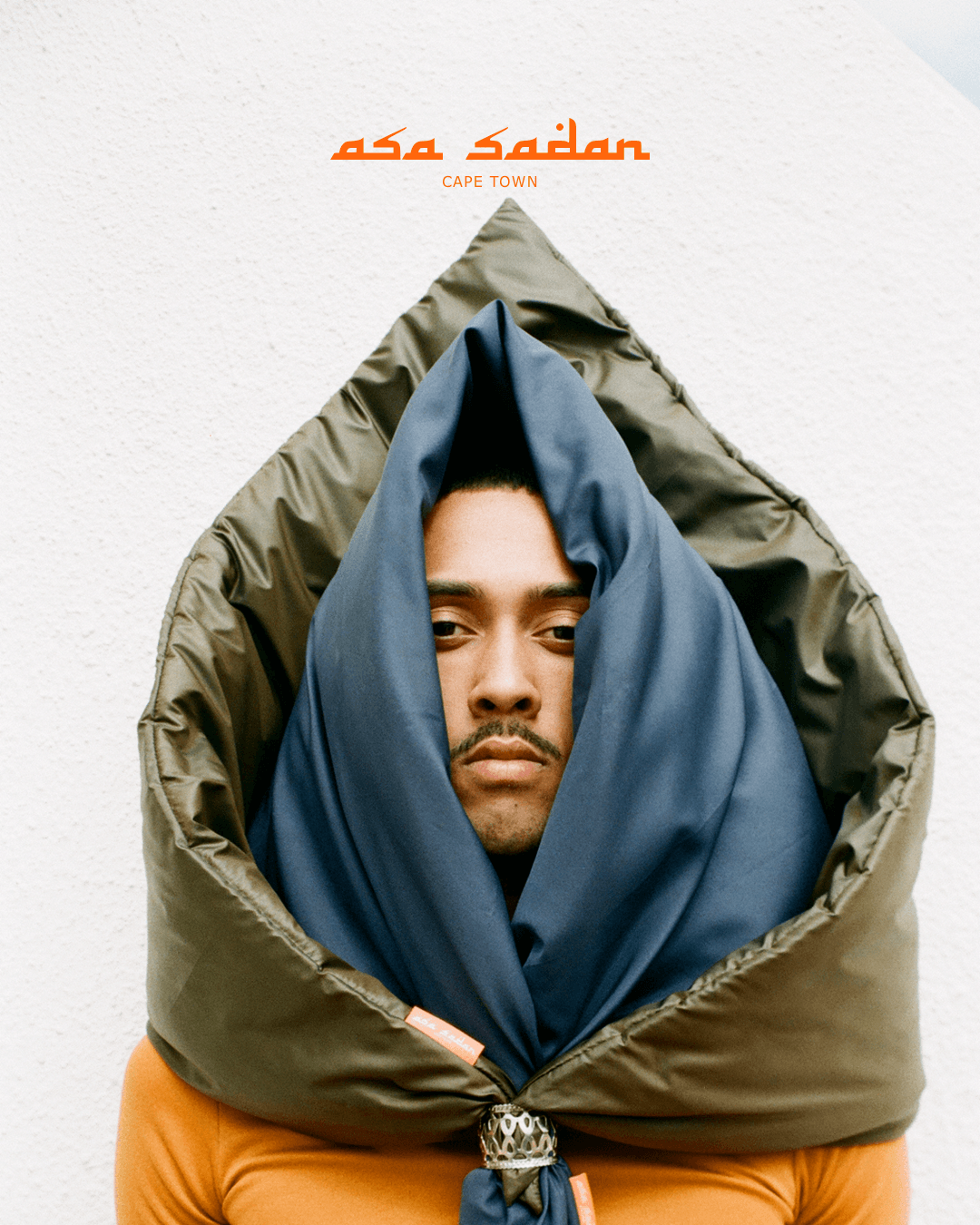

This journey between design and commercial product would eventually lead Imran to applying at Central Saint Martins for a masters program in Business Administration, merging artistic and creative practice with contemporary business principles – the school is somewhat of an enigma in the realm of fashion education, intensely difficult to get into, and has produced some of fashion’s most beloved designers and creatives from Lee McQueen, to Phoebe Philo and most recently creatives like Ib Kamara and Grace Wales Bonner. It is an institution that is built on fostering the most bold of fashion creatives. I think what makes CSM so unique is the array of pathways it offers; it is one of the few schools I know that encourages careers beyond just design. Imran’s initial drop for ASA SADAN “Dissertation Studies” is the evolution of his presented project at CSM; and is a commentary and inquiry into self-identity, cultural identity and how luxury can be reframed.

“I was in lockdown alone for four months, in London, only interacting with the cashier at the local Sainsbury’s every now and then. That time allowed for some deep reflection. I read a lot of books on South African history in tandem with strategic and psychological prescribed texts, and from that understood that there are so many stories that have not been told – or that we have barely begun to archive. In my own schooling background, SACS and UCT were both founded by Cecil John Rhodes, and we were taught that this man was a hero. When you do your own research; the truth is incredibly different. Uncovering the reality of how our country came to be made me realize how important South Africa actually is – the Dutch East India Trading Company would be valued at around $7-8 trillion in today’s terms. That’s around four times the value of Apple. That level of wealth was generated through oppressive systems and structures, in the advancement of colonization, and then we had apartheid; so I think it cannot be overstated how very new the idea of liberation in this country is. So when I was conceptualizing the label, and looking at my own heritage as being a Muslim, coloured man in South Africa, I wanted to address the stereotypes of how we have been boxed in stylistically – as ‘street’ culture. So on one hand I wore G-star and Nikes as a representation of our culture, and then on civvies day at a traditional white boys’ school – I am getting mocked and made fun of for doing so. My practice is therefore centered around breaking those narratives and boundaries, embodying our culture and heritage in the luxury it so deserves to be portrayed in, and I think when we understand fashion as the manifestation of identity and personality, we can see how powerful it is not just aesthetically, but also culturally and socio- politically.”

This sentiment shared by Imran, among many other moments in our conversation, is what informed my opening statement about him as a creative director. When we talk about intelligent design, we are not talking about design that is academically certified – or validated by any traditional models – rather, intelligent design is that which is created from the ability to view the multi-dimensional function of design to literally shape the world. It is the ability to understand how it has shaped the world until now – and then to reflect on how it should be done going forward. Good design advocates for equity through the prioritization of quality – good design, or true luxury, is the stripping back of everything we believe about materiality and novelty; and instead allowing fabrication, or construction, to serve as a symbol for the inner lives of oneself and one’s culture. This is the kind of design that fascinates me – that we see from other designers in South Africa such as Lukhanyo Mdingi, Thebe Magugu, Sindiso Khumalo and Rich Mnisi – among many others, established and emerging. In talking about whether he will build a collection or continue with drops, Imran says, “I think because we are really emerging as a luxury market in this country, it’s assumed that one can easily make 10 or 15 units of a garment. Factories here are looking at hundreds of units to pay their staff, maintain the facility etc – I am more interested in moving away from the model and timelines of excessive amounts of clothing made. I want ASA SADAN to show design that is relevant over time – to have pieces we make available to our community over two or more years rather than seasonal offerings. a work in progress, but I think the small process changes we can do in-house as one example, can hopefully contribute to shifting our ideas of quantity of product equating to quality.”

“To be able to be a creative director, you need to be able to understand every process. But you always need to be able to look around you, and see the value, skill and essence of the people that can create with you. All these hands are essential in building a brand. I am adept in technical understanding and articulating details, but can’t sew or cut a pattern at all! ASA has taught me to be incredibly diverse in the way I wear many hats – and I reference Lukhanyo (Mdingi) when I say this: ‘the power of the collective is greater than that of the individual’.” Imran says on this concept of creative direction. Speaking to Imran, I am affirmed at how much more we need in the way of educational spaces. We discuss institutional education, and the lack of infrastructure in South Africa; “Aside from institutional education, there is the grass-roots, on the ground education. One has to be connected and have their ear to the ground – there is a knowledge that just cannot be taught. It’s up to us as a collective to come together and create a library of resources.” With the pandemic, I have felt a sense of isolation even within the spaces that I have worked in and with the many incredible people I have come to know and talk to. I really feel enlivened by this conversation with Imran – there is a wisdom with which he speaks, and conveys critically the kind of conversations we need to be having in South African fashion, and honestly, I am thinking about podcasts, archives and the rallying of people together after this. We talk more about that, but I think that part of the conversation will have to have an ellipsis of intrigue…