PICHULIK is in the business of ornamentation as a practice; that ancient-as-bones thing that consecrates the body, its location on the earth, within the wellspring of life. When you purchase a piece from PICHULIK, you are participating in its sacrament — an object imbued with the very energies it evokes, because its very making honoured those energies in process as much as in its form. This, given this conversation with Katherine-Mary Pichulik, I know to be true.

As the existentialists would say, this is authenticity; when something is truly true to its origin or essence rather than just a representation. A necklace marketed as “sacred feminine” is just a symbolic signifier on an idea, but if its making process actually honours sacred femininity, then the object carries authenticity — it is being rather than merely appearing. As Walter Benjamin pointed out in his seminal, critical essay nearly a hundred years ago, in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, such a piece carries its aura — the singular, unrepeatable presence that lingers when origin, ritual, and intention remain intact throughout its creation. This is no easy feat in the mechanised world of today.

You see, PICHULIK is in the business of ornamentation as consecration; and consecration is a tricky thing to hold without diluting, or to practise without slipping into mere symbolism. Kat and her team take their roles as keepers of this knowledge seriously, ensuring that each piece is equally a gesture towards meaning and an artefact infused with it; an object carrying its own aura, its own sacred presence.

This, as Katherine shares in our conversation, is her responsibility as a jeweller and artist.

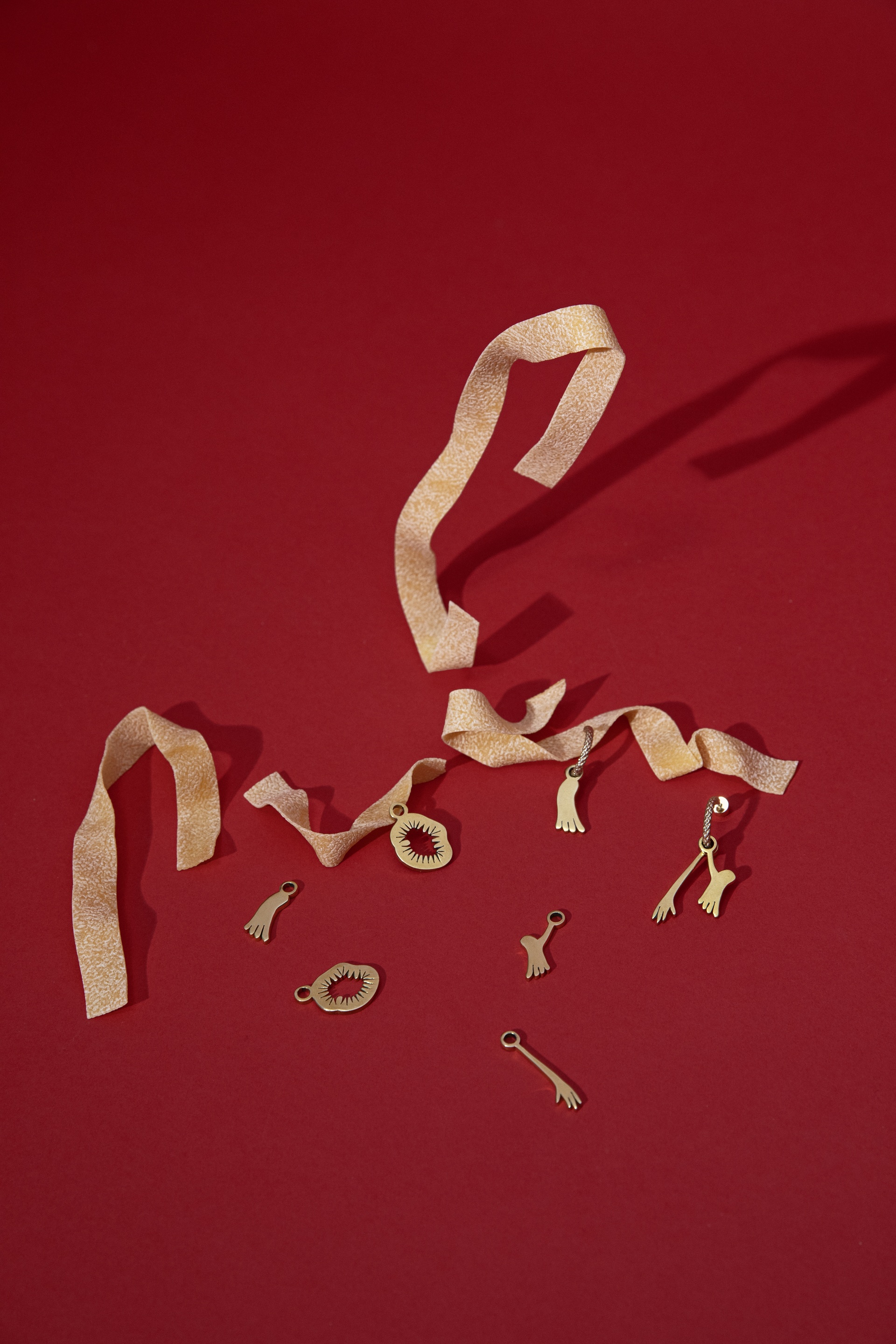

PICHULIK x Matteo Cibic Collaboration, photographed by Alix Rose Cowie @alixrosephoto

PICHULIK x Matteo Cibic Collaboration, photographed by Alix Rose Cowie @alixrosephoto

aruba bracelet photographed by JDee Allin @jdee_allin

Kat’s creative journey has always been guided by her hands, and is rooted in a restless curiosity. “I studied fine arts and then trained as a pastry chef,” she recalls. “I worked in a bakery in London, interned at Art Review, and when I came back to South Africa I was doing many things — writing for art journals, running a food stand at a market, bottling peppers. I’ve always made things with my hands — pastry, art, craft — I’m a tactile person.” That tactile instinct, a need to shape and touch, eventually led her into jewellery almost by accident, sharing that “in the evenings I would craft just to steady my mind. My ex-boyfriend’s dad owned a rope shop and would give me scraps of rope and thread. I started making pieces, wore them, and people wanted to buy them off my neck. That was the end of 2012.”

Katherine’s work soon caught the attention of others. A friend, Alix-Rose Cowie, photographed her pieces in the Company Gardens, and the images were picked up by the blog Miss Moss, the iconic journal of fashion’s blogging heyday, self-described by its writer, Diana, as a ‘Compendium of Radness’. Shortly after, ethical Kenyan brand Laleso invited her to accessorise their Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week runway show. “Suddenly, what was just a random hobby became a business,” Kat says. The early days of PICHULIK retained an intimate, communal energy — a principle that remains present at PICHULIK’s atelier, today. “I’d have girlfriends come over in the evenings, I’d cook for them, and we’d sit in a circle while I taught them how to make pieces so we could fulfil orders. Very quickly, it evolved into a brand.”

For Kat, jewellery has always been inseparable from heritage and storytelling, and her own heritage points to the North African tradition of intricate ornamentation and textile embellishment as a women’s pathway through identity and social connection. “My grandmother was born in Algeria and there’s a strong lineage of ornamentation, especially textiles,” she explains, and that growing up in a single working-mom household in the early ’90s, Kat was surrounded by costume jewellery, unconsciously absorbing its language; “I unconsciously linked big sculptural jewellery with agency and power,” she says, “In my family, jewellery has always been a storytelling mechanism. Not big diamond pieces, but keepsakes — objects with meaning and intention that are passed down.” Though PICHULIK intersects between the delicate and nimble, to the big and bold, the voice retained is always a declaration of womanhood and femininity as a pronouncement of strength.

This is Goddess work, true to its meaning of omniscience.

Of her design philosophy, Kat notes that, “I’m fascinated by alchemy — taking materials that aren’t considered precious and, through intention, design, and handcraft, transforming them into something valuable,” she explains.

Kat’s conscious choice to work with materials sourced in Southern Africa renders PICHULIK wholly dedicated to local craft, and has given the brand its distinctive aesthetic and material quality across rope and hardware, and semi-precious stones from Southern Africa; materials not often associated with the decadence of jewellery-making, though through Katherine’s eyes and hands, even the most industrial or humble components are imbued with elegance. “I always see each collection as an episode of a female protagonist’s journey. I can look back at each one and know what I was going through at that time — what the medicine of that collection was. These objects are the medicine I’ve needed, the wisdom consolidated into form.”

shimenawa earrings photographed by JDee Allin @jdee_allin

PICHULIK x Matteo Cibic Collaboration, photographed by Alix Rose Cowie @alixrosephoto

wave earrings photographed by JDee Allin @jdee_allin

Her creative process is both deliberate and exploratory, a practice she likens to foraging, with forensic intent. “I’m gathering information; from history, from philosophy, from whatever I’m reading, and then a word usually emerges. For this next collection, it was ‘Lacuna.’ It means a pregnant pause, where absence is incredibly full. That idea then starts to shape everything — the stones, the colours, the forms.”

“We work predominantly with industrial materials and hardy Southern African stones like jasper and tiger’s eye. Over time the work has become more refined. In the beginning it was all embellishment and beading, but as the brand and I matured, restraint came in and with restraint, comes depth.” This commitment extends beyond aesthetics into ethical practice: “We don’t do gold plating because it would have to be produced overseas. We’re committed to local job creation and handcraft. Our ropes are manufactured here or in Durban. Procurement decisions streamline our aesthetic. At the core, I’m interested in transformation — helping women reflect on their lives and ask: with what I’ve been given, can I make gold? Can I make magic?”

Kat has always approached PICHULIK with a commitment to integrity and intentionality, building a brand that is uncompromising in both practice and principle. This is what I referred to in terms of production authentically matching its outcome, and as Katherine shares with me, I’m all the more convinced PICHULIK is a blueprint for what is possible, ethically. “We’re a completely vertical business. Everything happens in-house — procurement, design, collateral, retail, wholesale. That’s allowed us to grow intentionally,” she explains. Central to this ethos is a refusal to compromise value: “One of our commitments is we never discount. When COVID hit, our revenues dropped to 10%. We took out debt to keep our staff employed, but we would not discount. To do so would devalue both the maker and the woman who wears the piece.”

Kat contrasts this approach with the broader industry, noting that many jewellery brands outsource and call it “curated jewellery” — essentially buying off Alibaba catalogues. “There’s little commitment to Southern Africa, to people, or to skill development. We’ve always done the opposite.” This ethical framework is similarly grounded in how the team itself is supported, in a way that is true to a practice of cultural sensitivity within South Africa’s context; “Our team is majority Xhosa speaking. Language is power, so we bring in a facilitator to support contract signings and performance reviews. Agency is fair wages, yes, but it’s ensuring people can advocate for themselves, and express themselves, as fully as possible.”

For Kat, culture, care, and integrity are inseparable from the work of PICHULIK. “A few years ago, two of my longest-standing employees were found to be stealing materials and reproducing work to sell at markets. It was the rest of the team who identified it, stood by the brand, and protected our team culture.

Written by Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za