In asking Dee about what it means to reflect back, looking at her younger self writing raps to her role now as an artist & performer, she says ‘’You know, when you start this thing with excitement – it’s driven by that feeling you have about music, that always felt so close in your heart but somehow far away through the TV – and what you see is people having money, being happy and always having fun. With that signalling, I thought it was going to be my best life. I started writing in English, I even have an EP in English which most people don’t know about, but it wasn’t enough for me. There was this whole part of who I am – in my deepest core – that needed to come out and that switch to Xhosa is what made me speak the way I wanted to be heard. That taught me that it’s not just about the message -it’s about the delivery; it’s about how you say the things you need to say.” This switch is the kind of action that writes the future; the kind of move that cynics (and such) would say is bad for business; with English being a predominant language in the world, and it’s a ridiculous fallacy to be successful is to fit into this narrative – and as the homies of experimental band Off The Meds show, winning a Swedish Grammy in isiZulu is possible; it’s already happened. Dee goes on to say, “It was for my hood – I wanted messages to get through to them. The moment you speak English in Khayelitsha, it’s ‘you’re not for us’ – and in Xhosa, they were hearing what I was saying. The whole family is included and involved, then. I’m not doing this to appease some people who can’t speak my language – if they like it anyway, that’s amazing, but my focus is my hood and my people, and expressing to them the sounds of who we are as people. The crazy thing is, people who don’t understand my language do love it – they love my flow, and the energy, and that’s how music is; it’s more than just the words, it’s the whole experience, layered together.”

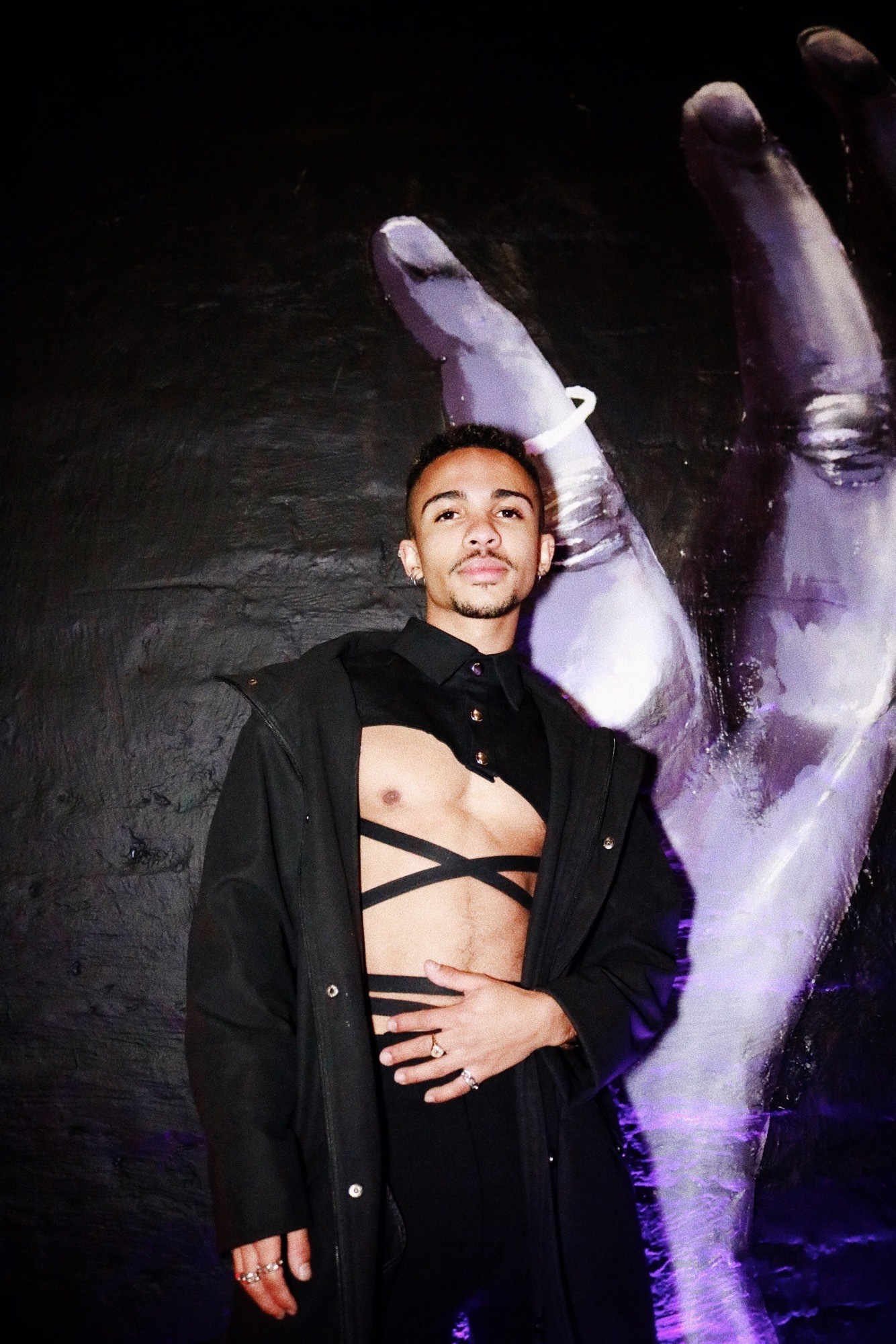

A big part of her career has been an unbreakable relationship with adidas – who dressed her for a Sportscene campaign early on, “I think they liked the way I dressed their pieces. I’m not a typical sponsor baby, I put a bit of me in it so it’s not just adi head to toe. My favourite is mixing thrifting with adidas pieces, and now I’m in my fourth year with them. Two years ago they made me an ambassador, which has been such a great joy. I do deserve that – and the love is so mutual, it’s shown me the power of relationships in the industry; and how music and fashion are so closely linked.” Even in this, Dee expresses how she shows up as herself, always. With an almost insatiable demand for artists to adopt cycles of trends and styling that reflect what the brands want from influencers, Dee shows brands what they need; to have representatives that bring their garments into real, lived contexts, “I’ve seen one thing happen in my hood, that people noticed I was wearing a lot of adidas. In Black culture, the 16th, 25th and 26th of December and the 31st and 1st is when kids beg their moms to get them the biggest drip ever. It’s the school holidays, it’s festive. On the 16th one year, I walked outside and I saw a ton of kids in adidas tracksuits – so many! And they’re saying to me “Dee, jonga, look!” and pointing to their fits. Even adults were fitted out. This one old-timer, whenever it’s a Saturday and he’s heading to a local tavern, he’s got his tracksuit on and his Stan Smiths, he always comes past my house – ‘how you feel about my drip?’ – it’s wild to me. They gave me a nickname – Ndida – which is the Xhosa slang for adidas. I don’t know, that’s some kind of influence.”

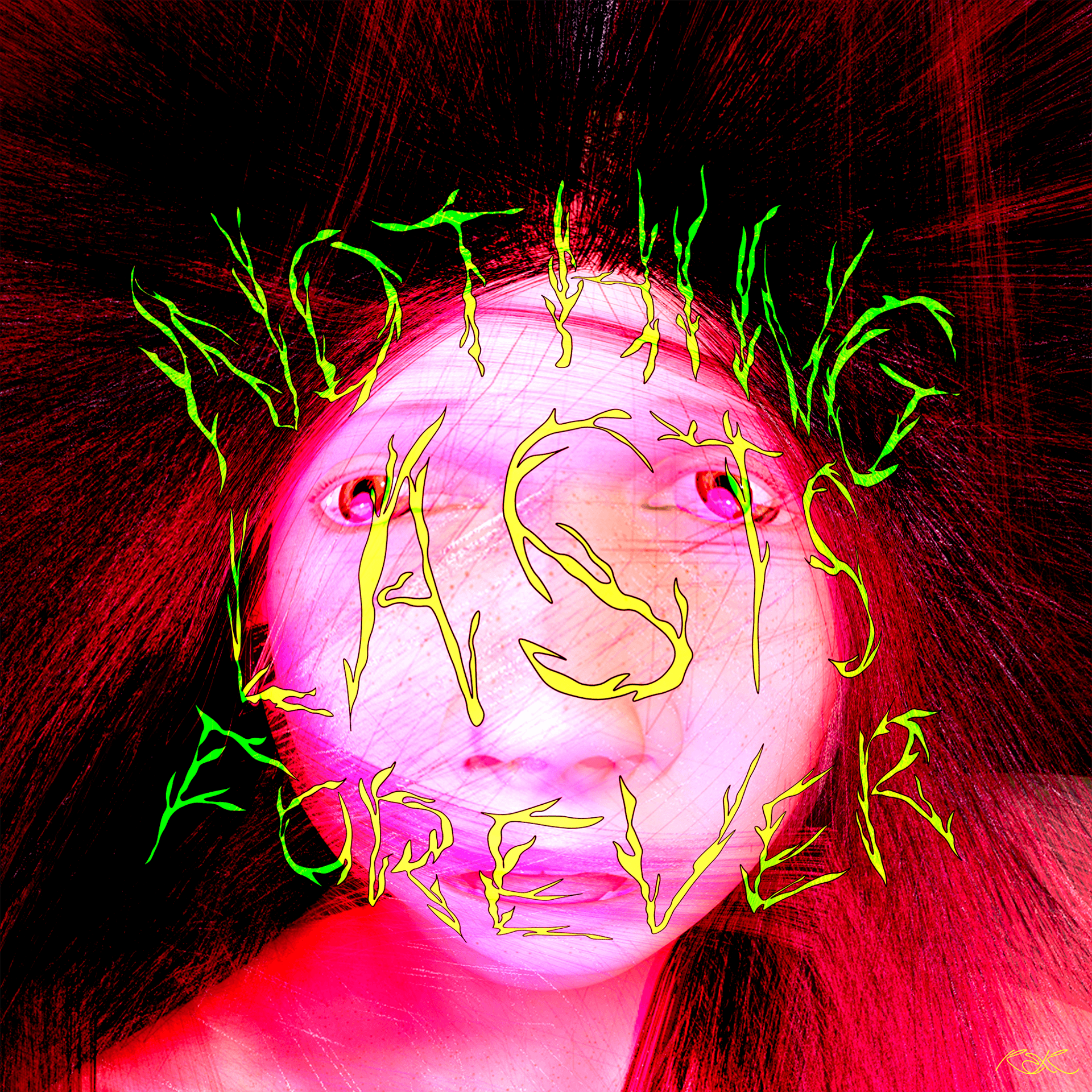

Although the last few years have been a rise to success for Dee, these years have simultaneously been tormented by deep losses. Dee’s decision to share this with us is marked by her belief that one has to share the whole story; not just the glory, but the full picture – so her followers and community know that life is always this polarity and dance, that success cannot always keep the pain at bay; “Two years ago my mom died, and I thought I was going to be fine – that I would just grieve, and get on with it, you know? The show must go, type of mentality. Except I couldn’t grieve – I wasn’t sad – I just couldn’t be alone. So I was going out everyday, taking people out because I needed to be around people. I was drinking a bit too much, and then my grandma died – and then a month after that my great-grandma died, and a month later…my two aunts. All the women in my life, one after the other. These were all the moms of the family. I didn’t know how to handle that, it was like all the strength in the family had left in the space of six months, and I was on my own. Alone, in a way I didn’t know was possible. I wasn’t able to show up – my professional conduct started slipping – and then, the final blow was the onset of writer’s block. I couldn’t string together a single verse. I was heart-broken, and it’s like I had left my body.” It’s that age old understanding of being alone, even in a room full of people – that sometimes, we are all we ever have. Yet with Dee, there is a love for that is hard to articulate – an impact that she has wherever she goes.

Recent Comments