Tandekile Mkize Is South Africa’s Meta Stylist with His Visionary Approach To Fashion Storytelling

Tandekile Mkize’s approach is truly meta; hence his Instagram moniker, the meta stylist. With fashion as his chosen medium, he moves fluidly between roles from stylist, to editor (most notably at Twyg, where he has been instrumental in advancing our understanding of sustainable fashion, particularly within the African context), curator, and fashion director. To be “meta” is to operate with an awareness of the bigger picture; to examine the frameworks, codes, and narratives that shape the thing itself.

In Tandekile’s work, this means interrogating fashion as a cultural text and identity, and expressing this innate understanding through a broadly-scope practice; one steeped in sartorial consciousness – from the fabrics Tandekile favours to the stories that he elevates, and one only has to pass their eye across one of his works, to understand the depth of intention and cultural literacy embedded into every choice that he has made.

Lately, Tandekile has been busy; in between all he does, he curated Threads of Renewal, an accompanying group show to Twyg and Imiloa Collective’s Africa Textile Talks. It seems his love affair with fabrication is deeply rooted, and as he’ll tell me later, someone recently referred to him as a “man of the cloth.” Stylists and editors are often praised for the big picture — the composition of the entire thing — but it would seem Tandekile is motivated in this moment by the very granular threads that bear it all together.

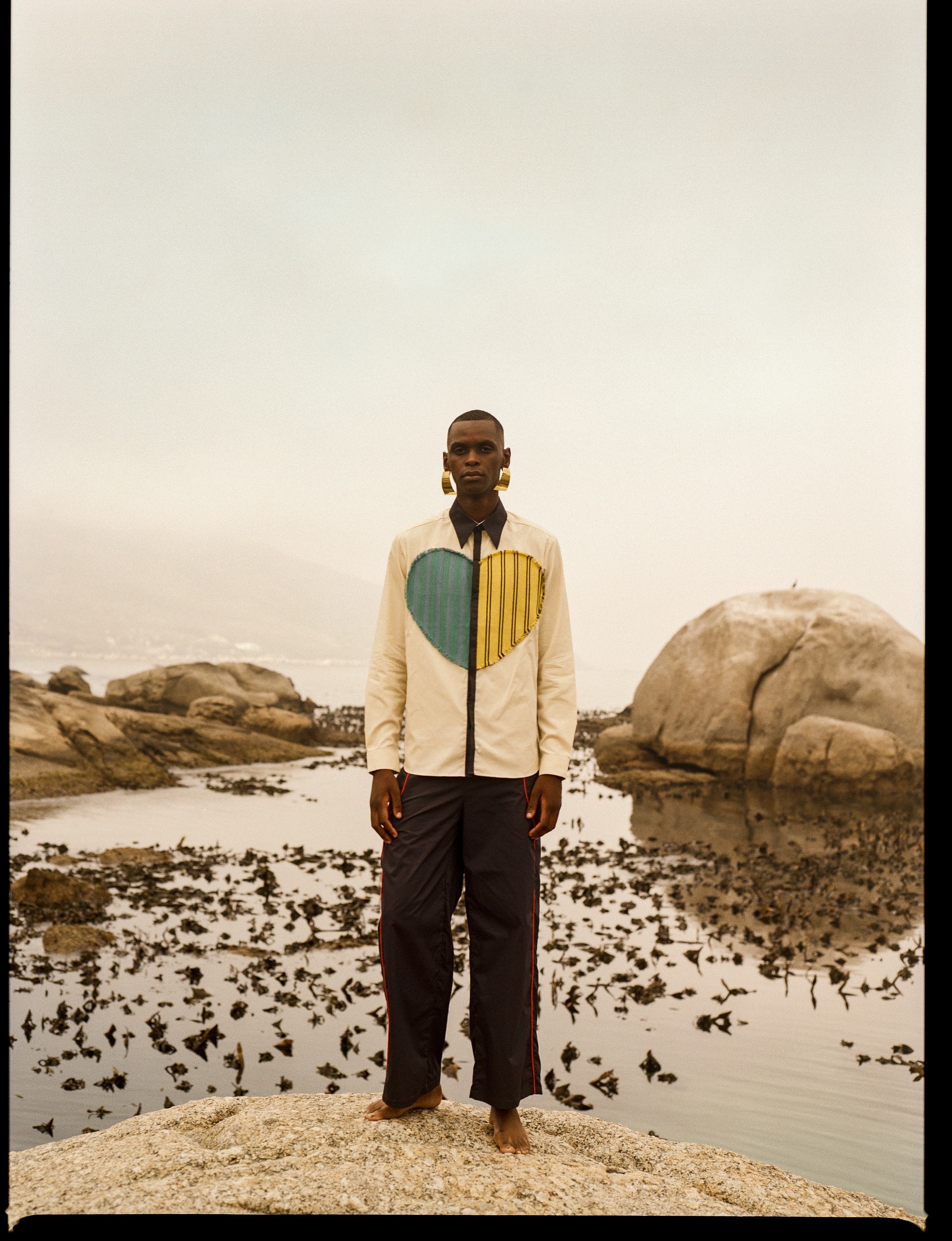

Styling by Tandekile Mkize, photographed by Andile Phewa

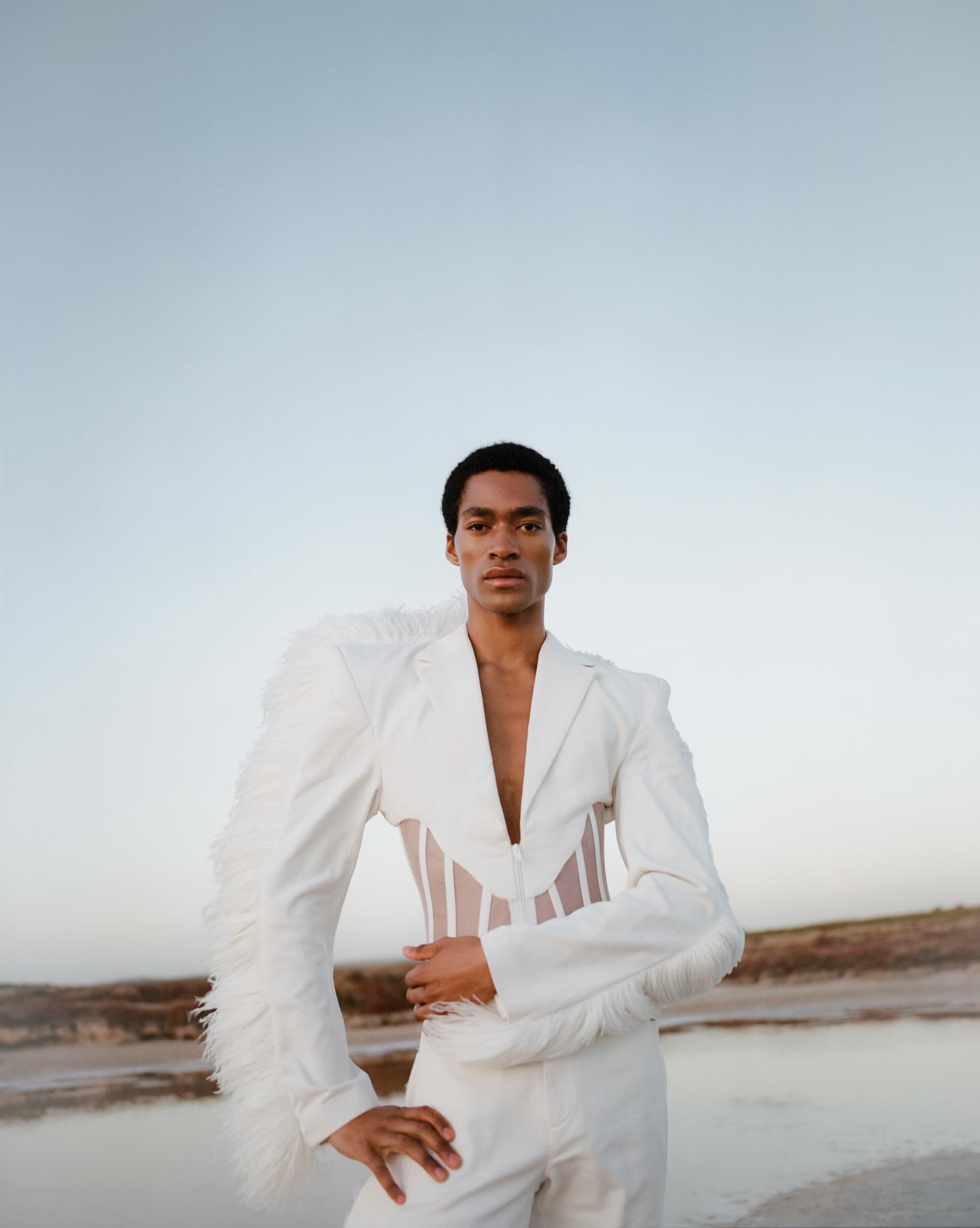

Styling by Tandekile Mkize, photographed by Dan Carter

In this way, Tandekile is, yes, concerned with the image and composition, but more importantly; he is devoted to the stories and histories embedded within fibre. After all, without fibre; fashion styling would be somewhat bare. I can’t think of a better return to essence than this, for someone whose creative expression and career present a loom of entwined ways to understand fashion beyond mere commerciality.

His cousin played a pivotal role in introducing him to the world of fashion, as reminisce, “my cousin would switch on Fashion TV and I’d just be around. It really opened my eyes to this world. I became so invested in who the models were and what shows were happening. He’d get annoyed because every time a model appeared, I’d always mention their name. I was that annoying kid! So it all grew from there and then I went off and figured things out myself.” From that iconic channel, FTV, with striking models darting down runways as pulsating music blared, many fashion kids had their first real taste of the industry’s energy and spectacle. For Tandekile, it was equally the glamour and a drive to uncover the stories behind what he was witnessing that sparked his enduring fascination with fashion.

“I’d say my path started when I was at UCT for about a year but didn’t last much longer. I had asked myself, ‘What’s next? What do I actually want to do?’ I wasn’t focused or invested in school at all at that time.” After leaving university, Tandekile had to chart a new course for himself. Fashion had always been a calling, but practical realities led him to jobs at call centres. With the money he earned, he began buying clothes and cameras, connecting with friends through social media and collaborating on editorial concepts.

Initially, Tandekile styled and modeled himself in projects inspired by his personal transitions. Over time, he began to negotiate an ensuing, broader perspective and around 2018, as photography gained momentum and analogue photography burst on the scene, Tandekile grew fascinated by the medium, sharing that “Friends would shoot me, and I became fascinated by the camera. I got my own and started shooting my own work, even exhibiting some pieces. Having photography skills has been really useful, as a stylist and fashion director, and understanding image composition is important. Photography demands total commitment though, so I’ve never been serious about photography — it’s something I’ve parked for now.”

On his styling philosophy, Tandekile notes, “Starting from a personal place with real pieces has shaped the stories I want to tell. It’s important to layer fashion stories with deeper meaning. I’ve come to understand that when you embed layers of yourself in these stories, they carry more emotional resonance. Fashion is also a way to archive your own story, and the stories of others.” For Tandekile, this meta approach to styling has naturally evolved into curatorial work, and where styling often remains confined to ephemeral digital imagery, Tandekile’s role as a curator brings fashion into three-dimensional space — a physical presence that revitalises the relationship between maker, wearer, and audience. Ultimately, this roots fashion in community and dialogue and in this way, I’m increasingly convinced that Tandekile embodies precisely what we mean when we say “a fashion storyteller.”

Tandekile is Twyg Magazine’s Fashion Director, a collaboration that began in 2020, sparked by a creative partnership with stylist and spiritual healer Noentla Khumalo during the heavy COVID-19 lockdowns. “When bans eased slightly, we felt frustrated but full of energy,” he recalls. “We needed an afternoon to come together and create an editorial called Shift in Flow about the period of transition we were in. Transitions are a recurring theme in my practice. That project reflected on the times, what it meant to be in fashion, and where fashion could potentially go.”

Styling by Tandekile Mkize, photographed by Dan Carter

Styling by Tandekile Mkize, photographed by Dan Carter

This initial collaboration led to an ongoing relationship with Twyg, where Tandekile now works alongside Ky Boshoff and Jackie May as part of the Twyg Fashion team. Reflecting on his curatorial role and the broader scope of Twyg’s work, he explains, “Bringing together the ecosystem across the continent to discuss innovation and what’s happening has been inspiring and insightful. It’s important to make sure the message is carried across. We get to witness so many beautiful moments, like local designers collaborating with textile makers in Uganda to develop fabrics for their collections, as an example. This cross-cultural exchange of ideas is incredible. It localises the idea of pan-Africanism; borders dissolve and we can actually connect with one another.”

Beyond the collaborative spirit, Tandekile is deeply invested in the ongoing renaissance of African fashion, particularly the revival and preservation of indigenous craft practices. “I’m very excited about indigenous craft practices. With our work, there’s exposure to so much more. Many young designers are tapping into this, which is exciting,” he says. “The richness of African fashion means we’ll never run out of stories.” For Tandekile, this blend of tradition and innovation is central to Africa’s fashion future.

Reflecting on a recent exhibition he curated, Tandekile describes how it was about striking a balance; “It was important to represent both traditional techniques and contemporary expressions — looking at the past and how it can inform the future,” and he emphasises how African textile traditions use cloth as “a vessel for storytelling and cultural heritage,” a concept he wanted to convey while also “pushing it further and imagining new ways to tell stories through cloth.”

Indigenous practices reveal that cloth has always been deeply intertwined with other senses — sound, taste, and ritual — in both ceremony and daily life. This multisensory understanding challenges our modern perception of fabric as merely practical wear, and extends the very act of weaving, a complex and ancient craft, as a remarkable achievement of human ingenuity and cultural expression. I’m still amazed at the thought of ancient human beings drawing the connective possibilities between plant fibres and the living world around them; and everything that has occurred in the way of fabrication since this moment.

Tandekile’s fascination similarly includes the spiritual and healing qualities of textiles, particularly as explored in the exhibition’s Cosmology of Materials section. Featuring works by Wacy Zacarias, Yemi Awosile, and Djamila De Souza, this segment examined the four elements as “material collaborators.” Tandekile notes how Wacy, a spiritual healer and textile practitioner, “understands plants and materials with healing properties and incorporates that into her textiles to give them healing and protective qualities.” This nurturing and protective aspect of what we wear, he says, proves that clothing is an intimate extension of self with profound cultural and cosmological significance.

I’ve caught Tandekile this week as he’s wrapped Threads of Renewal, alongside his showcase at Greatmore Studios. Amidst the recent launch of his role in FIELD BAR’s extraordinary campaign and the daily drum of life, Tandekile’s current creative focus is about slowing down and embracing depth over speed. As our conversation winds down, we fawn over Bubu Ogisi’s IAMISIGO debut at Copenhagen Fashion Week the night before — another etch, we agree, in the immense blossoming of Africa’s fashion renaissance.

On his own creative journey, Tandekile shares, “I’ve gotten into weaving recently; it requires time and attention.” As a multi-hyphenate, this tactile, material exploration feels a natural consequence of Tandekile’s depth as a fashion storyteller; from eyes to hands. “Someone once asked me if I’m a ‘man of the cloth.’ That made me think. I wouldn’t necessarily describe myself as one yet, but there’s definitely curiosity there! Before I take that title on, I know I have a long way to go.” Lastly, Tandekile’s advice to aspiring creatives is simple; “Just do it. Even if you don’t end up where you thought, taking the leap and putting yourself out there is how you discover your path.”

Written by Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za

Recent Comments