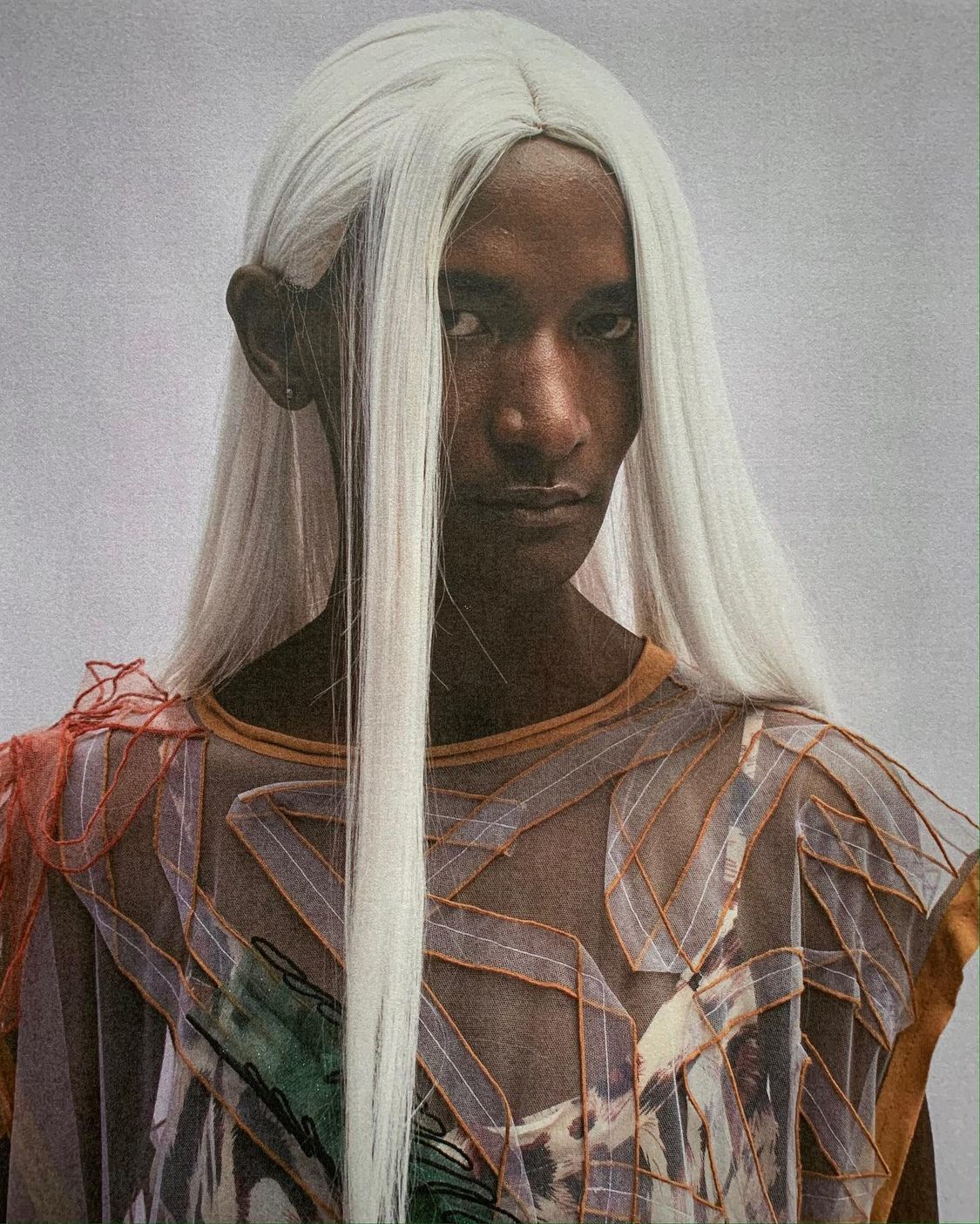

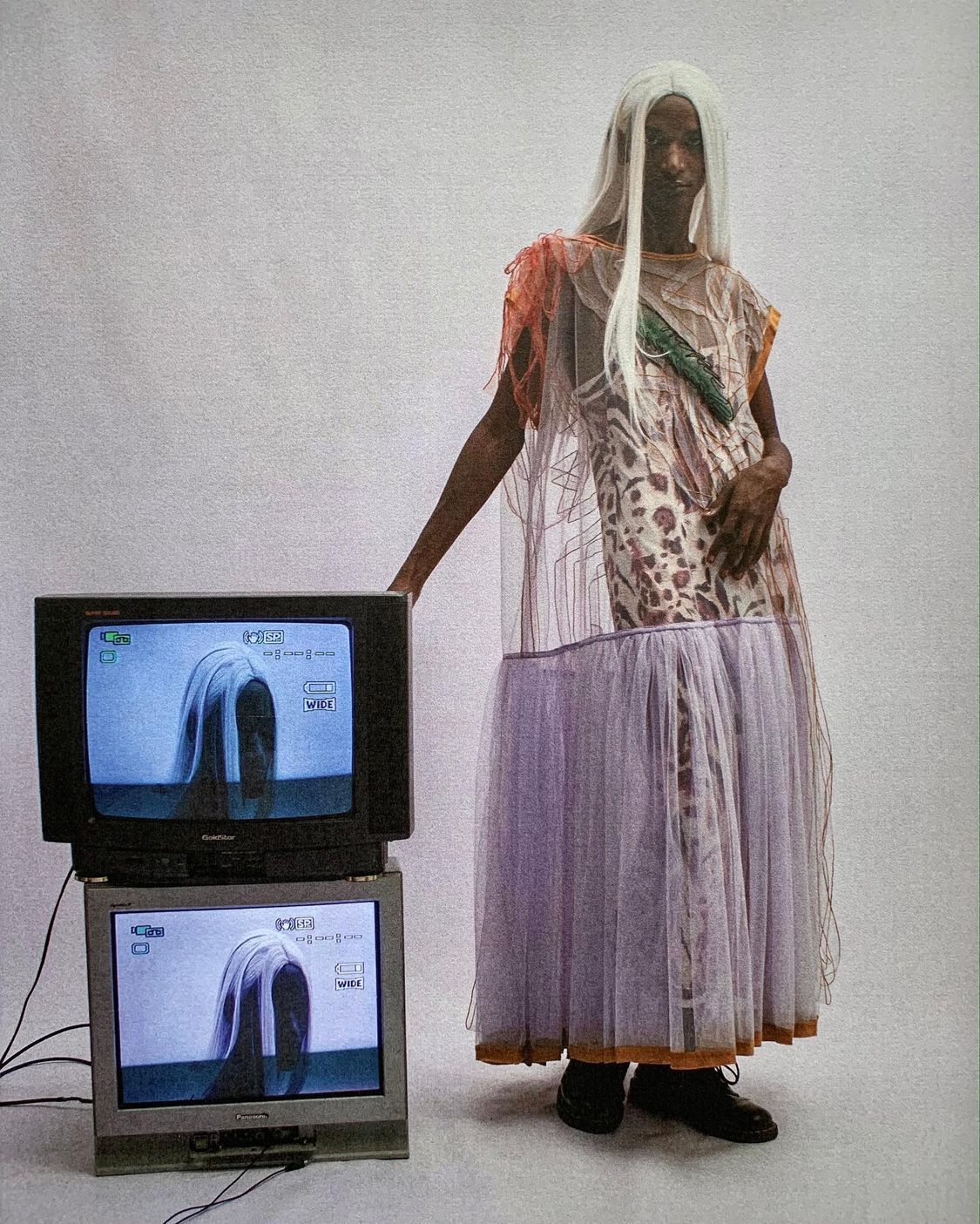

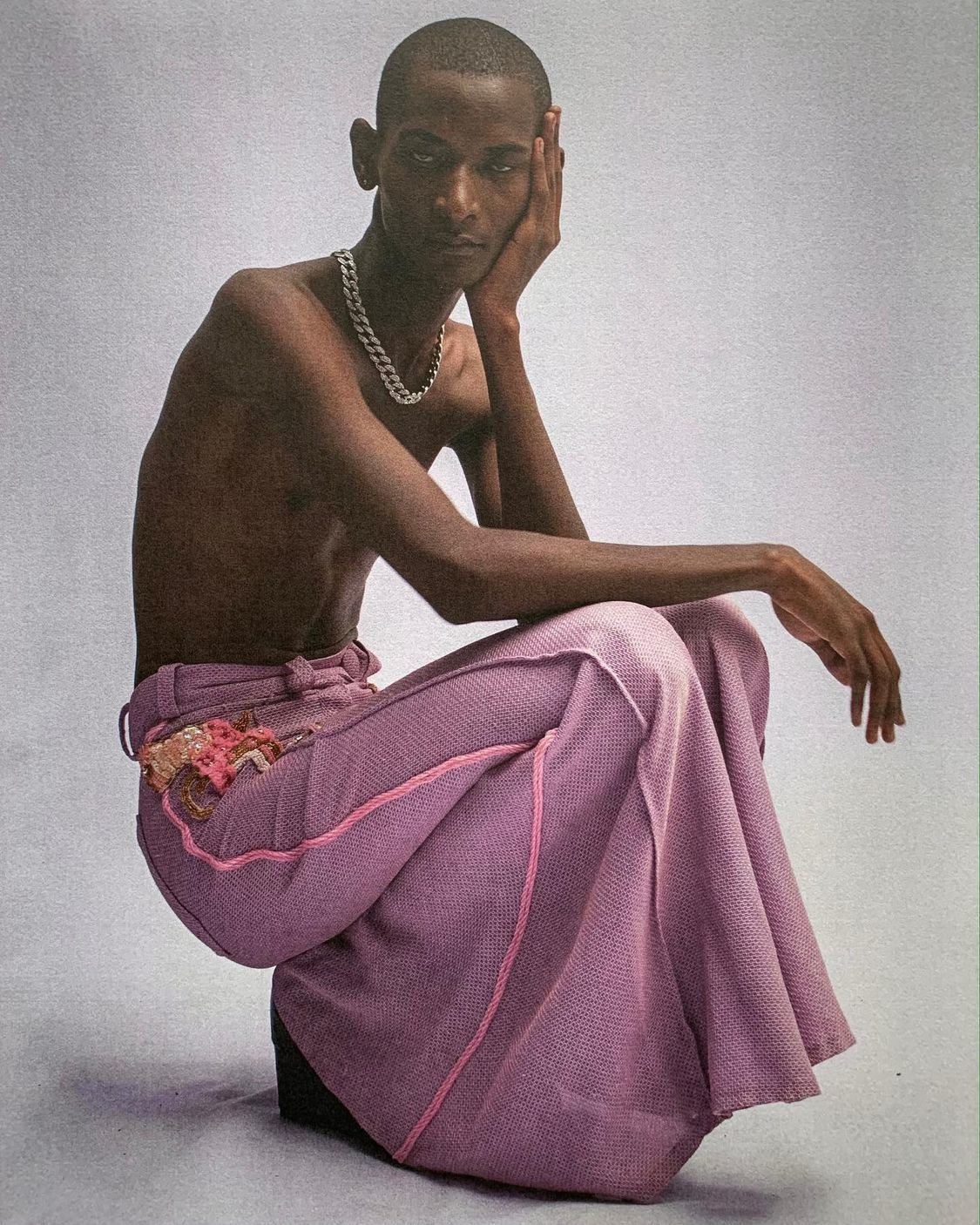

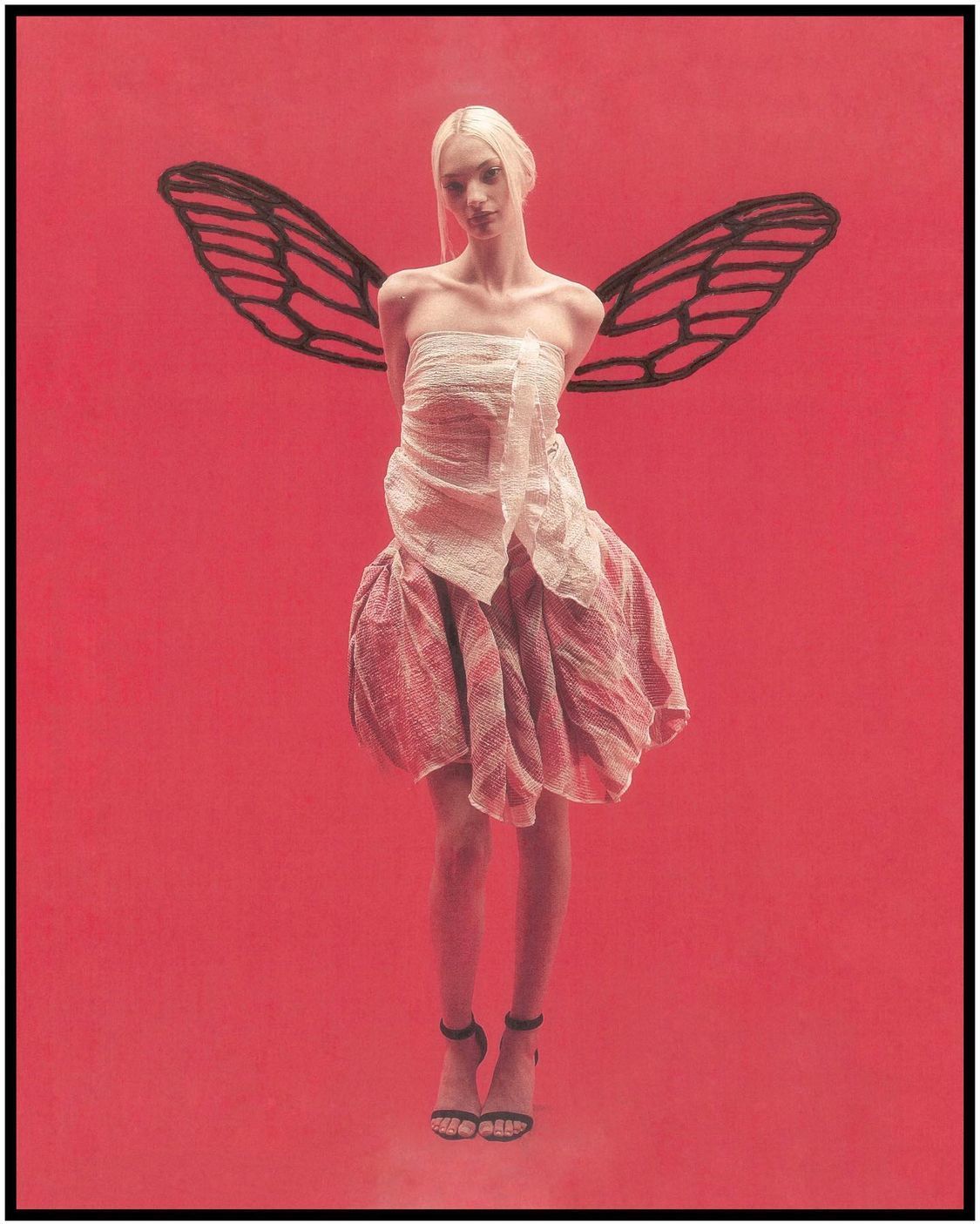

Tzung-Hui Lauren Lee’s artistic and sartorial consciousness takes flight

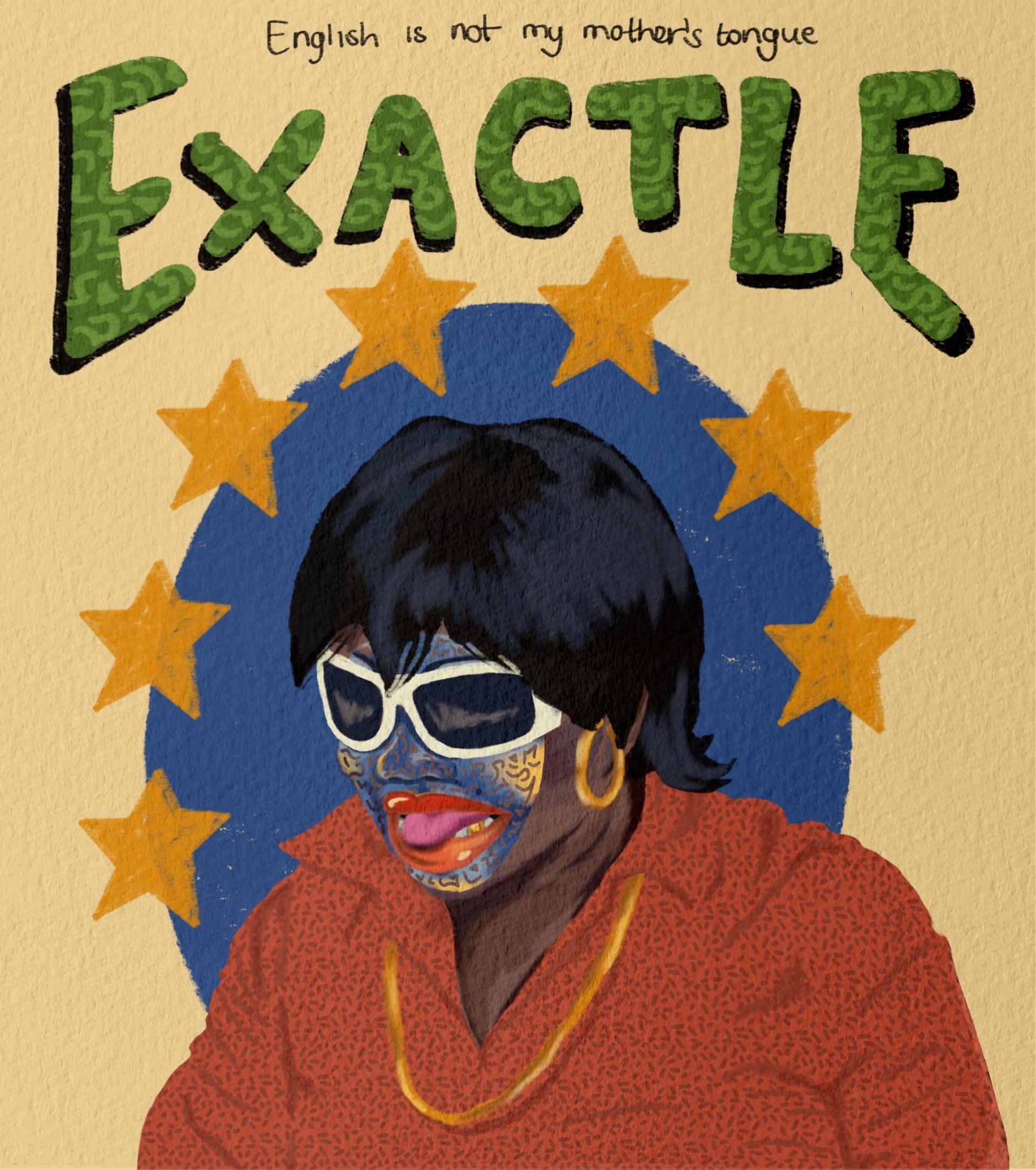

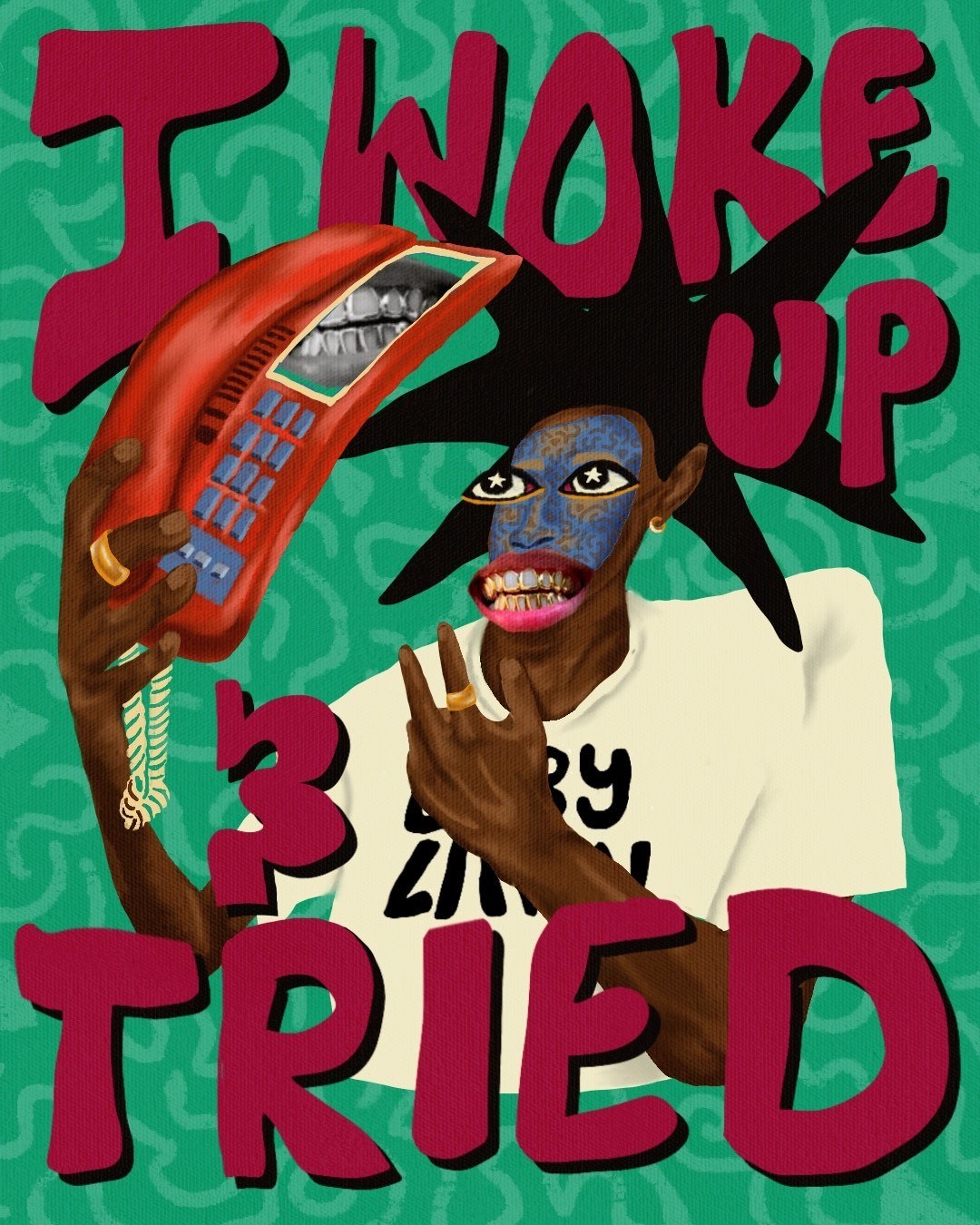

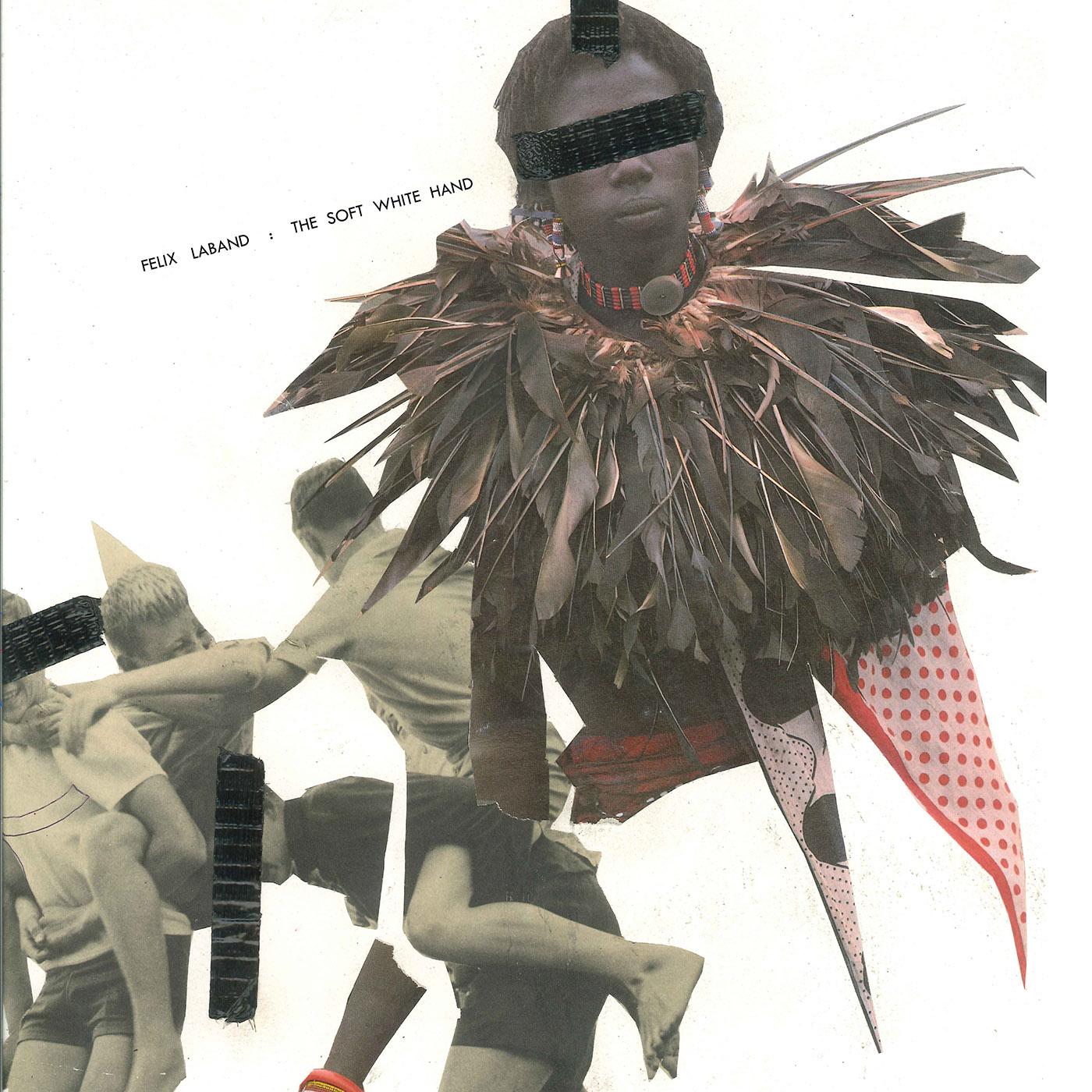

In the age of Instagram, I count myself lucky to have URL friendships that blossom through DMs – the cosiness of text communication, of shared interests and understandings. Tzung-Hui is one such being – an artist and ardent lover of fashion – whom I count among them. We even hopped on a Zoom call earlier this year to meet, fangirling over fashion – set design – and all the possibilities of the world; cognisant of each other’s social anxiety, yet determined to connect. Tzung-Hui is a South African-Chinese artist based in Johannesburg, whose practice is vividly expressive of her deep ancestral roots, cultural self-inquiry and experience as part of the Chinese diaspora – and for Tzung-Hui, Chinese philosophy, folk art and tradition are required more than ever in both preservation and reverence. Within these dimensions, Tzung-Hui’ yields a variety of multidisciplinary mediums; sculpture, paper-making – writing inspired by the ancient expression of Chinese calligraphy – and delving into digital reality rendering, too. Further than this, is Tzung-Hui’s love for fashion; for us both, is an experience that has been innate and in our bones. I stand in awe of her stylistic evolution as an artist, and Tzung-Hui’s commitment to the full expression of her essence & inner world.

“I was always interested in fashion. I didn’t want to be a fashion designer – I just knew that wasn’t what I wanted exactly – rather something related to art or creative direction. I applied to Parsons, and being 18 at the time – my art teacher discouraged me from going to New York on my own at such a young age. So, it was Wits in the end – for fine art. While I was still at Wits, I think I kind of forgot what I was doing art for; it’s very easy to get absorbed into the system, and foresee the normal routes that tend to be laid out for artists coming out of universities. After I won the BMW competition, I found a better sense of flow – and it’s so interesting, because there have been so many coincidences since then, that have shown me this art practice is exactly what I was meant to do.” Tzung-Hui says, reflecting on her formative years and the dissolving boundary between art and fashion within her practice; further than says, Tzung-Hui explains, is the psycho -spiritual nature of this calling, “My Chinese name ‘Tzung-Hui’ means ‘ancestral wisdom’ and it’s also a Buddhist phrase, and my studio is in my shrine at home. Not many people know this. So I always light incense, and pray or meditate, before I work – and allow things to just flow. In that way, I’ve found a way to root my artistic practice in flow.” I’m reminded of a term I’ve seen used for Tzung-Hui’s work, ‘’psych-physical energy’’ – to which Tzung-Hui responds, “I’m really interested in different ideas of Chinese philosophy. At Wits, we worked a lot on decolonial lenses – and I’ve had to interrogate what that means specifically to me. My dad is Taiwanese, and his dad was trying to escape Mainland China, and then my mom is from Beijing – and so there are these different diasporic issues. My practice is a way to work out my past and lineage; I think actively trying to work backwards has allowed me to open up to my own viewpoint and context, and ‘unthink’ everything.”

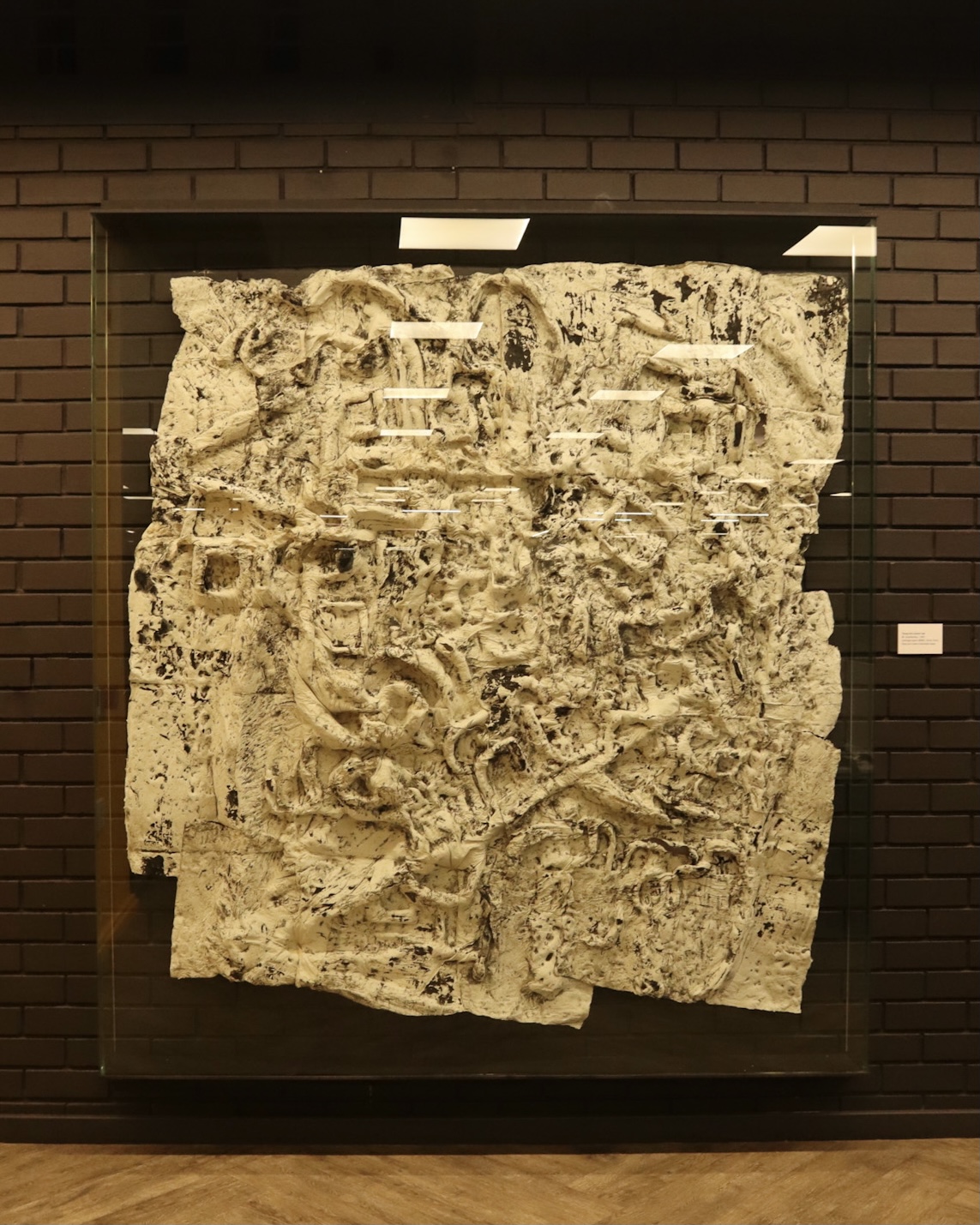

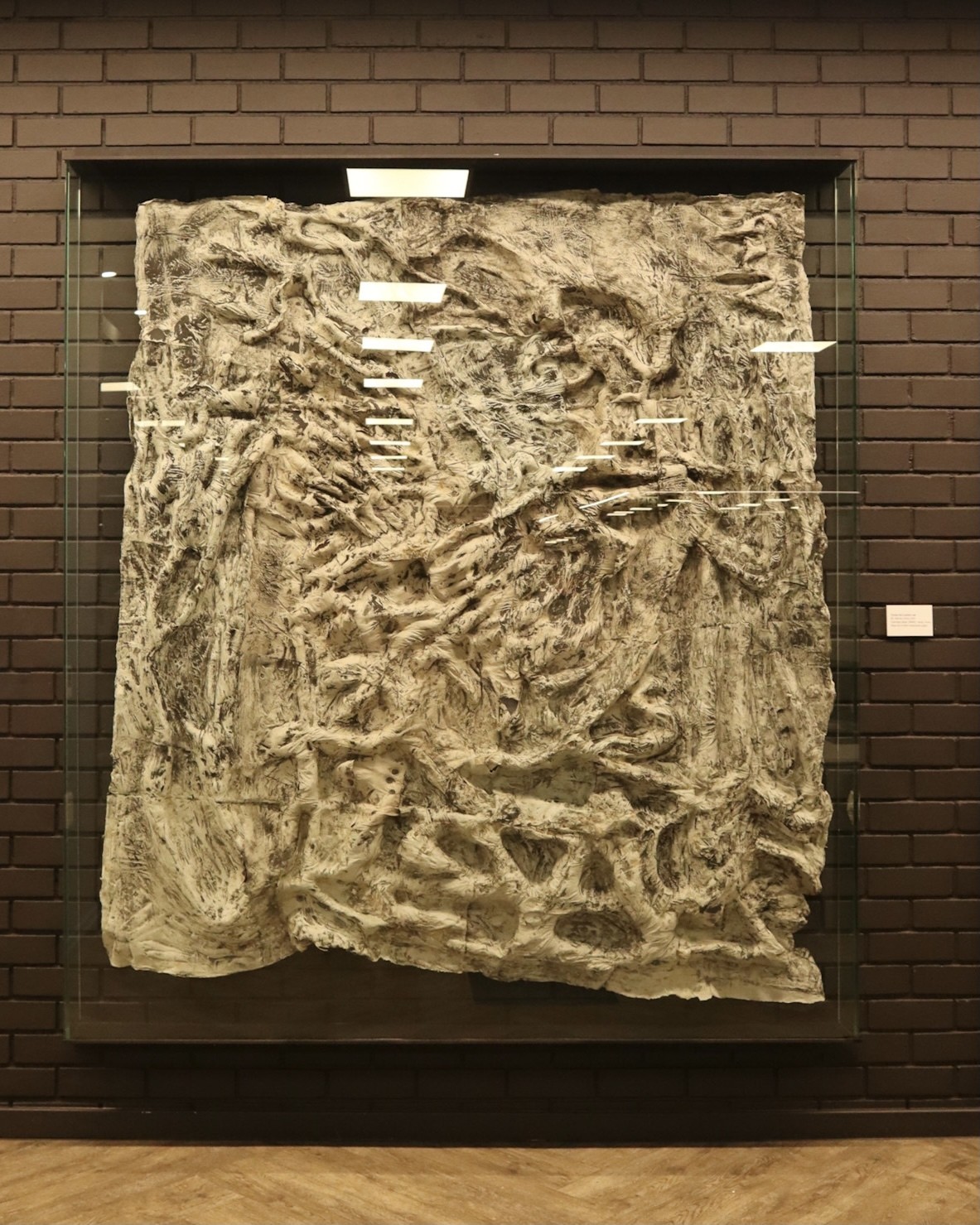

Tzung-Hui’s Buddhist practice forms the heart and nature of her family’s spiritual life – and it has allowed Tzung-Hui’s intuition to be a nurtured compass. Buddhism’s beauty – among many, many things – is its cultural-site specificity, and symbiotic way of being. Buddhism in one region of Asia, will take shape through the cultural roots of its position through the people and communities who shape it; for Tzung-Hui, there are no linear or separate means from moving through Chinese Medicine, ancestral practice to Buddhism; this vast and rich fabric is part of her, and she a part of it. These threads lend themselves to Tzung-Hui’s artistic style,“I wanted to draw air – this mesmerising, intangible quality of life. But how do you draw something you can’t see? I really love looking at clouds moving – and then when I was in grade 2, my grandfather passed away. We had the burial ceremony in Taiwan, and from then the idea of burning things – the smoke as a transmutative – and I also watched this cartoon growing up that showed heaven as being in the clouds, in a Buddhist context – so the temples were all the clouds. When we pray to our ancestors, or people get cremated, or the smoke from incense – smoke and air become intertwined with each other. Thinking about these ideas led me to draw movements. My practice is a relationship between medium and meaning.”

With a decisive use of charcoal in her work, Tzung-Hui explains the medicine of earth that provides her artistic tools; meaning imbued down to the materials themselves, “For my drawing practice, soot is a material within the charcoal that forms the quality of air. Soot is what floats up to heaven towards our ancestors – and it gets collected into an ink, and becomes a physical block mixed with an animal hide glue. So, that animal had a life and so all these energies come together before I even begin to etch my work. I feel like there is a physical dimension that translates through the material.”

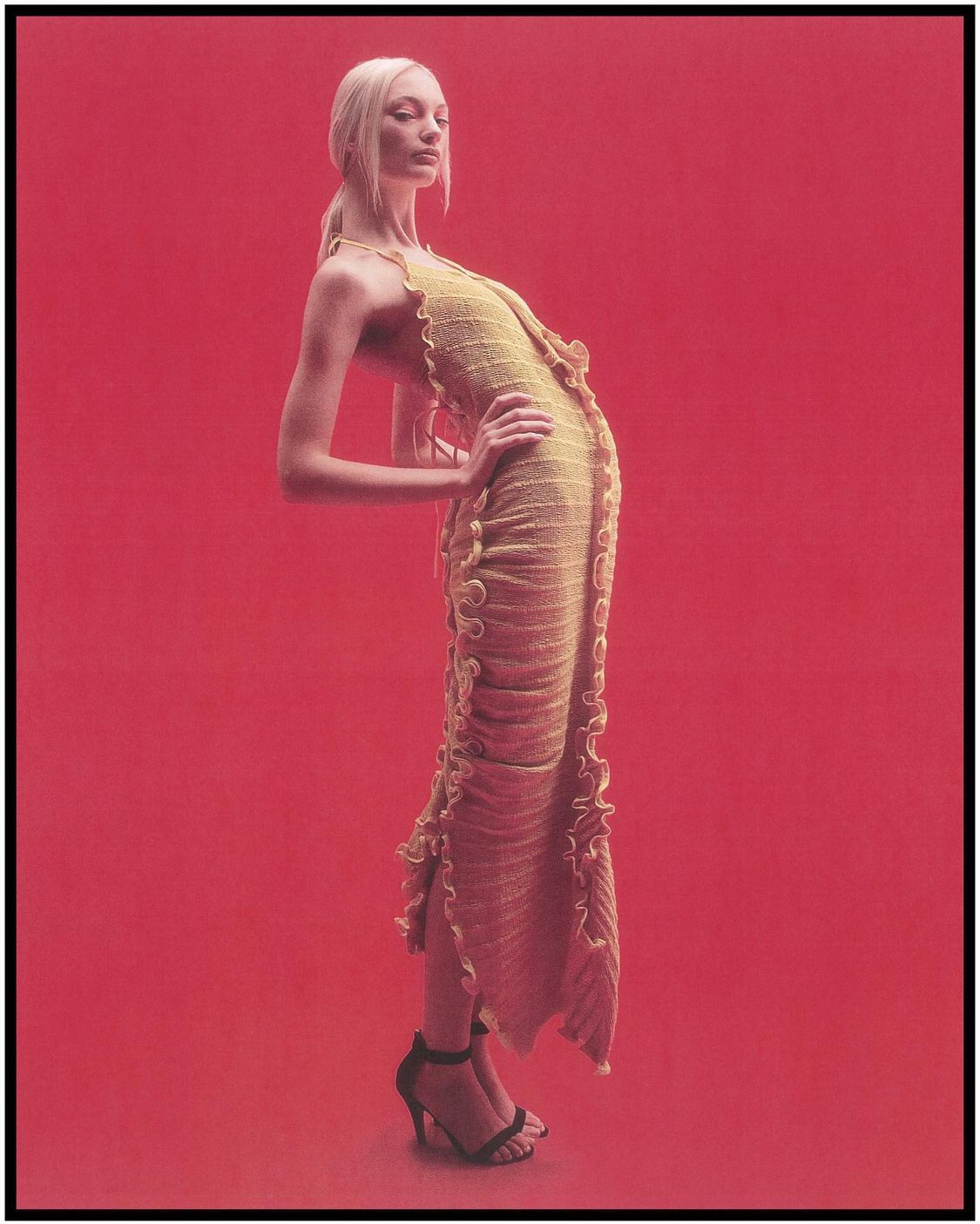

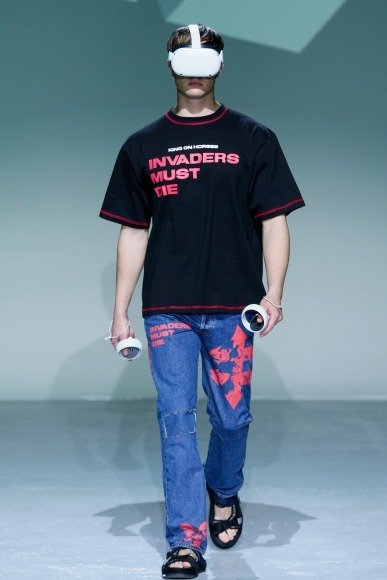

Tzung-Hui and I discuss the visual stimulation related to fashion – lauding over Rei Kawakubo in between – and she recalls way back in 2013, when she could have been a blogger, “I hoarded fashion journals, I could have been a blogger – I was so little at the time and trying to digest every fashion week and moment. Fashion is incredibly personal, I think – it is art, without question. Now, I’m so excited for fashion week & ready to watch all of them – this is where I know my sense of purpose is. Even when I draw, I listen to fashion podcasts. The creatives at that level are incredible – the worlds that they build. All throughout becoming an artist, I’ve felt the pull towards fashion; and when I was in Paris this year, it became a visceral path I needed to tune into. I’ve applied to Masters programs in Paris, London and New York.” Tzung-Hui sees a path ahead for set design; the immaculate and immense way in which fashion can be produced, particularly through a decisively artistic lens; “You are your artwork and the canvas when you are wearing your clothes. That’s fashion, it’s innate.” I couldn’t be more excited to see her consciousness expand and root in the world.

Written by: Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za

Recent Comments