Is there anything more profoundly majestic than horses? With eyes as deep pools of wisdom, lucious manes and unfathomable strong bodies; horses are etched in the consciousness of peoples across almost all cultures since time immemorial. From the Navajo in North America, to the Mongolian people on the Eurasian Steppes, to the Zulu Kingdom in South Africa, horses have symbolically represented many things to human beings, among them — strength, freedom, and status. We have, in one way or another, always asserted horses as the physical embodiments of the spiritual realms, our own personal power, and the social prestige of our communities. We can trace our earliest relationship with horses to the Botai culture in current day Kazakhstan, some 6000 years ago and to horses, we owe much of our feats in agriculture, migration and withstanding the earth’s natural forces.

Today, equine therapy is a well-accepted and continually studied therapeutic tool, in which human beings can improve their emotional, psychological, and physical well-being with the companionship of horses. Through activities like grooming, riding, and ground exercises, we can develop better self-awareness and build confidence and horses have shown to be deeply intuitive in their nature — and in their understanding of our complex and often messy species.

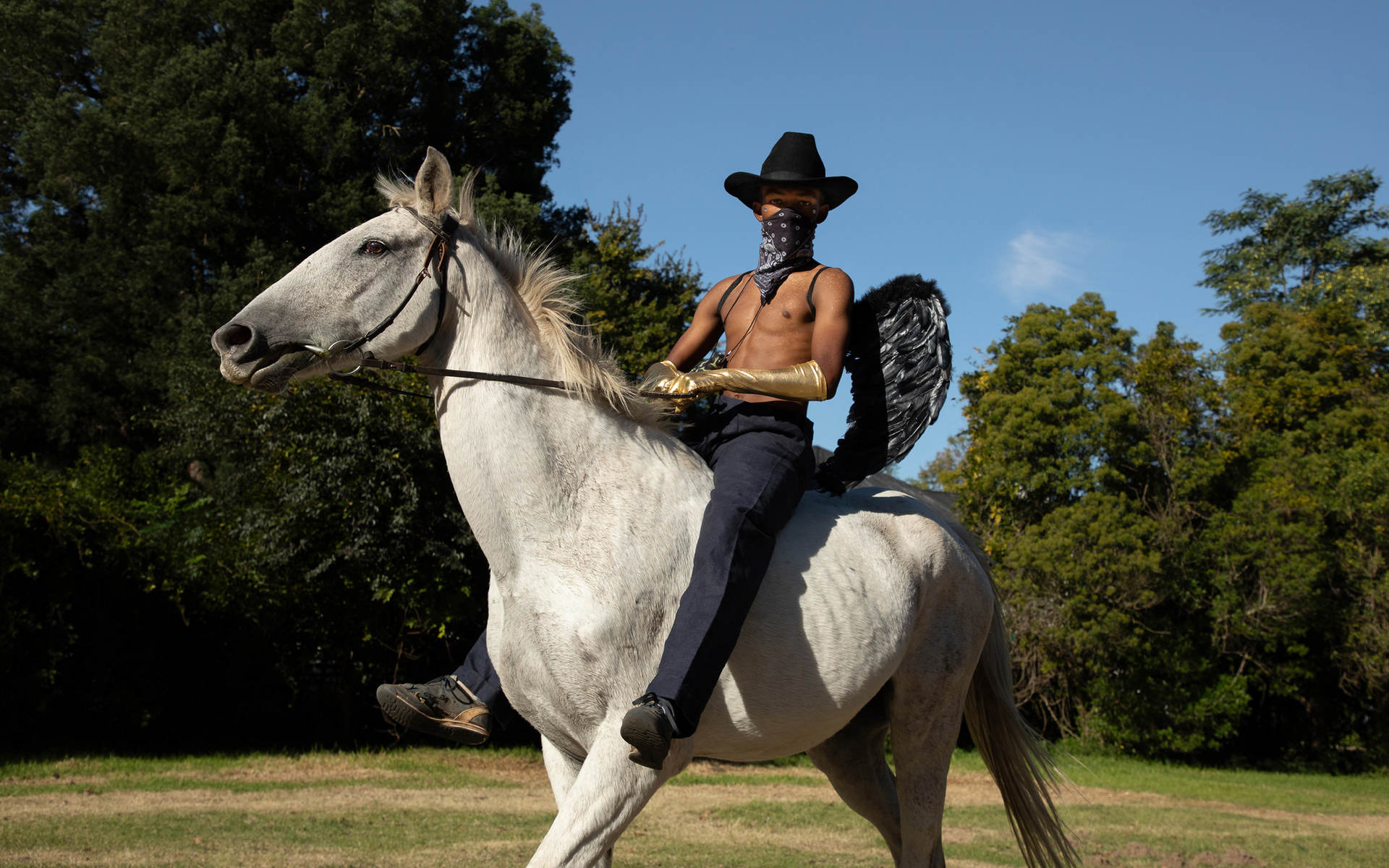

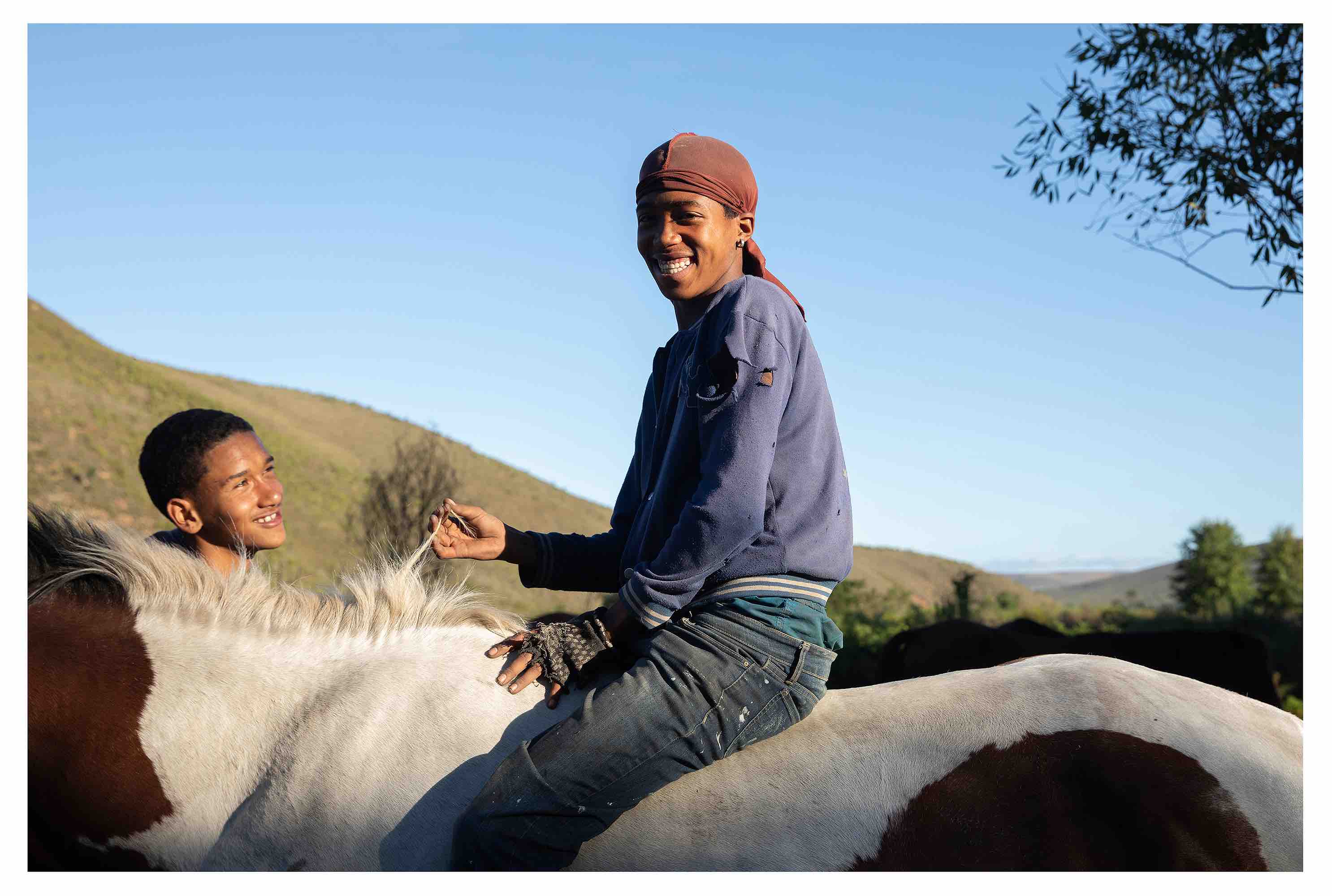

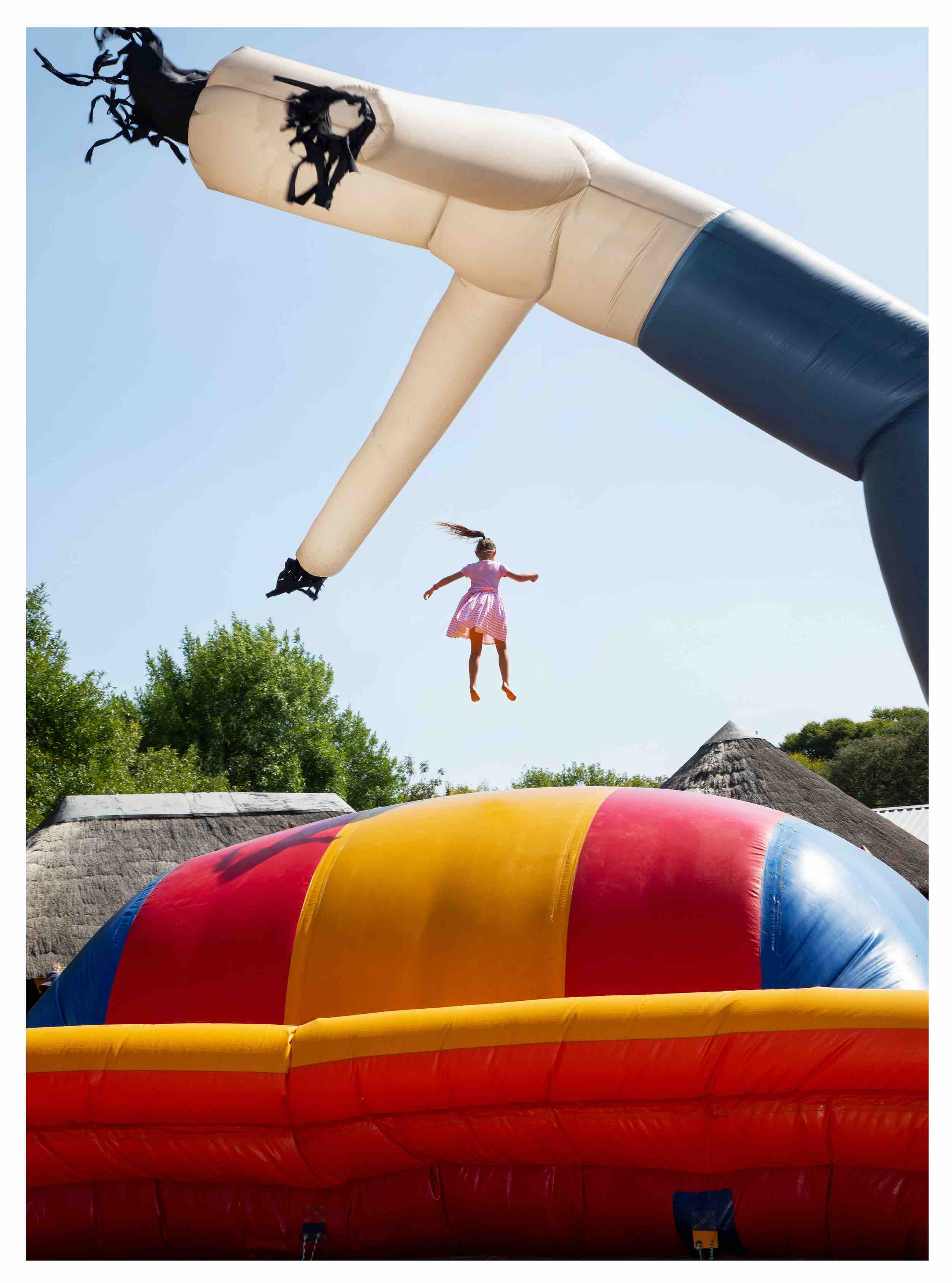

It is in this light, of the sacred bond between horse and human, that photographer Gabrielle Kannemeyer has embarked on an immensely personal and deep project, capturing South Africa’s thriving horse cultures outside of the dense, urban environments of the city. For Gabrielle, this project has initiated a kind of immersion in this work that artists often only ever dream of; the opportunity to become one with the context and experience of her chosen subject, and as she tells us later in our conversation — the journey is in fact, a whole and reverential return to her roots. As Gabrielle explains, “as part of a broader project capturing South African horse culture, I’ve become deeply involved in documenting a group of gifted young cowboys in a small valley known as The Valley of Grace. This old mission town is home to a vibrant community of youth who socialise, train, and ride wild-roaming horses. In addition to working on my project, I’m also teaching them photography. I follow the lives of these riders, aged between 9 and 21, as they navigate the remarkable worlds they have created for themselves.”

Photography by Gabrielle Kannemeyer

Though Gabrielle’s project is intended to span the country — the project began in the Western Cape’s Overberg region, a wildly fertile and mesmerising assortment of landscapes. From rugged mountains, to vast swathes of farmlands, speckled with the intertwining aqua-scapes of rivers; if you’ve ever had the pleasure of driving (running, cycling or simply being) in the region, you’ll know its expanse and glory in your very bones. The emotional sense evoked when I’m in the Overberg, even without any familial or cultural connection to the region, is kind of inarticulable — so, departing from my usual interview style for CEC, this interview is shared entirely from Gabrielle’s perspective; the only way which was fitting. As Gabrielle shares with us the life-giving and spirit-asserting ways in which horses, human beings and the lands of South Africa have heralded Gabrielle’s next chapter as an artist; the urge here for us all is to consider the ways in which soft-spoken call of the earth and maybe, our destiny, can find us at any time and change our lives forever; lest, we only listen.

Can you talk about how you became immersed in this project, and how it evolved to become that’s both long-term and now, part of the fabric of your life?

“My love for horses and people drew me into this project in the most unexpected way. At the heart of it all, I have my dad to thank for introducing me to horses.

He used to take me along when he visited his friend, Uncle Johnny, in Sandvlei, who had a couple of horses. While they had tea inside, I would “ride” around the yard with Uncle Johnny’s kids on some very kind and patient horses. Looking back, it was wild, as I must have been only about seven or eight years old.

It was also my dad who introduced me to the small towns in the beautiful valley where I now reside and work intermittently. He worked as a plumber in many of these towns and had family friends there. I remember getting so excited every time he’d say we were going to “Horsey Land.” I’d dash to the bakkie and jump in, standing on the passenger seat, eager for the adventure.

One memory that stands out is pressing my face against the window of my dad’s bakkie, trying to get a closer look at the kids riding horses bareback to the shop to grab snacks. Their horses would patiently wait outside for them. All I wanted was to join them, feeling a sense of magic that’s hard to describe. I thought they were the coolest ever (I still do).

Fast forward to two years ago, I came across a photo on a local horse group I follow on social media – a boy rearing on a massive Friesian stallion. That image reignited that same magic, and in that moment, the project began to take shape.

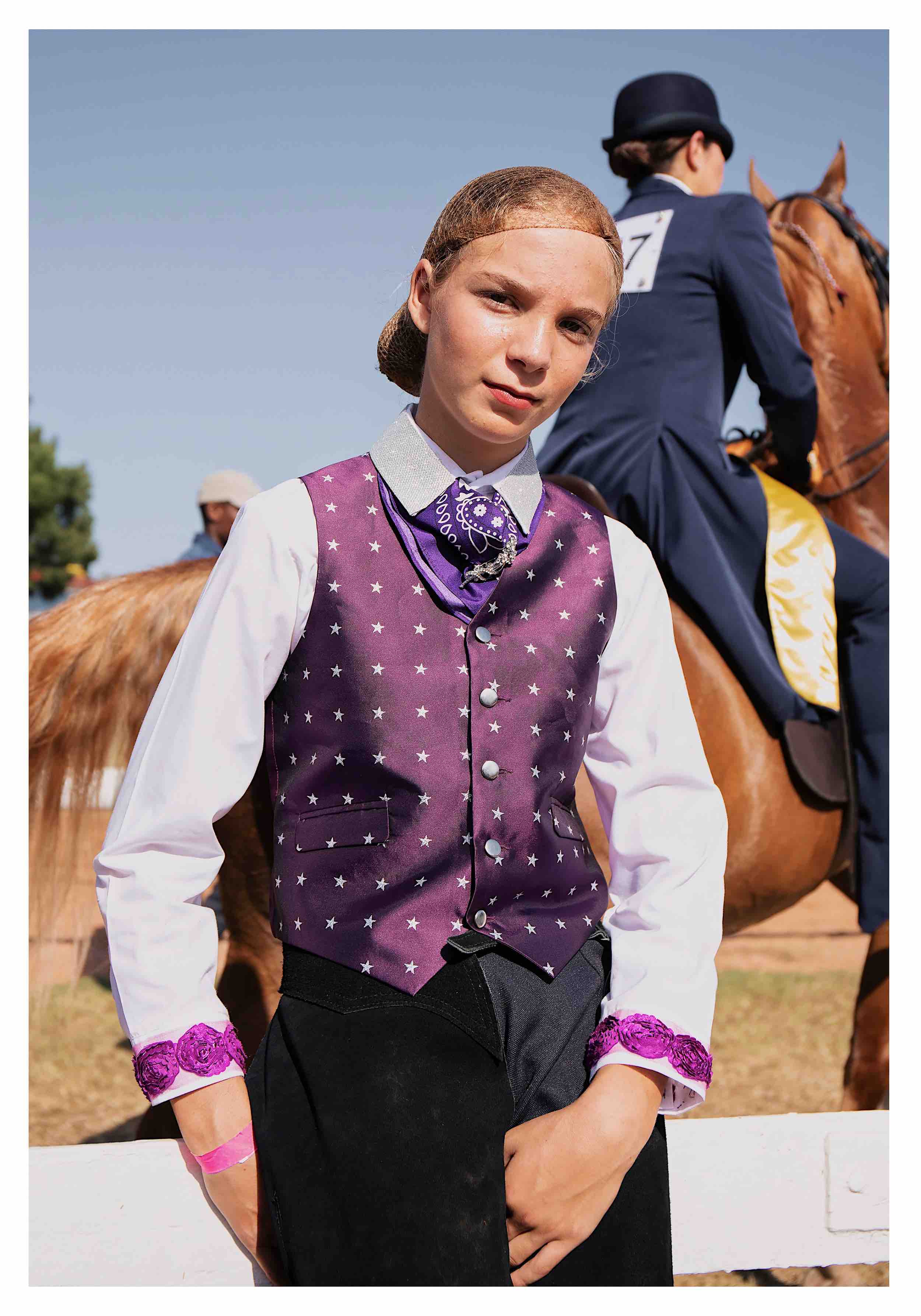

I initially tried to reach out to him and a few of his contacts, but without success. So, I started documenting local horse shows around the country while I worked out the details of the project.

Towards the end of that year, my health took a turn for the worst. I spent the following year battling these issues, which led to an operation to remove an organ that left me bedridden for a while. But during that time, I made it my mission to return to horses and fully commit to the project. I started riding again (after 15 years!) and threw myself into the project with renewed energy”.

You’ve travelled around South Africa, capturing horse culture – can you touch on some of the places you’ve been and what differences and similarities you’ve found fascinating?

“I’ve been following several show circuits, including the Saddlebred, Vlaam, Boerperd, and Friesian circuits, travelling from Swellendam to Bloem, Parys to Constantia, and many small towns in between. Next on my list are George and Moorreesburg, and I’m also eager to spend more time documenting Hackney pony shows and the competition culture surrounding them.

One common thread I’ve noticed is the deep desire for genuine connection in these communities. Human curiosity thrives in these tight-knit environments, and some of my most memorable experiences have come from simply wandering into places that piqued my interest and then diving down the fascinating rabbit holes they revealed.

The people I’ve encountered have been incredibly generous with their time, their hearts, and their stories. I often say to anyone who will listen—I started this project and visited these small towns because of my love for horses, but I stayed because of the people.

In small towns, everyone greets each other with a politely raised hand or gentle nod of the head, whether on foot or in a vehicle. One of the things I find jarring when coming back to Cape Town is that kindness on the streets isn’t doled out quite as generously. The contrast between the openness of small towns and the fortified nature of city life is stark.

Photography by Gabrielle Kannemeyer

When I first moved to a small town, I struggled to recognise people from a distance. Fast forward a few months, and I can identify the faintest silhouette from hundreds of metres away. I can tell who someone is by what they’re wearing from any angle or even by the horse they’re riding! I don’t mean to boast, but I can also name almost every horse across three neighbouring towns. The people I’ve crossed paths with along the way are some of the most inspiring and badass individuals I’ve ever met. The world is certainly better for them.

Many of the rural communities do however lack access to basic resources. These towns are often neglected and underfunded by government institutions which is such a pity because these communities are our gold. Travelling around the country during election time really highlighted this disparity, and it was an eye-opening experience”.

Your focus is the Overberg – this fertile landscape flanked by oceans and mountains, can you talk about this landscape as a photographer?

“There’s a reason so many artists have dedicated their lives to painting and documenting the undulating landscape of the Overberg. There is a contemplation the landscape demands when traversing through it. I am grateful for spaces that allow for that. I think I’m at my best and healthiest as a person when under the Overberg sky, this allows me to pursue the sharpening of my craft as a photographer”.

The communities across the Overberg – specifically, The Valley of Grace – what has their way of life conveyed to you as an artist?

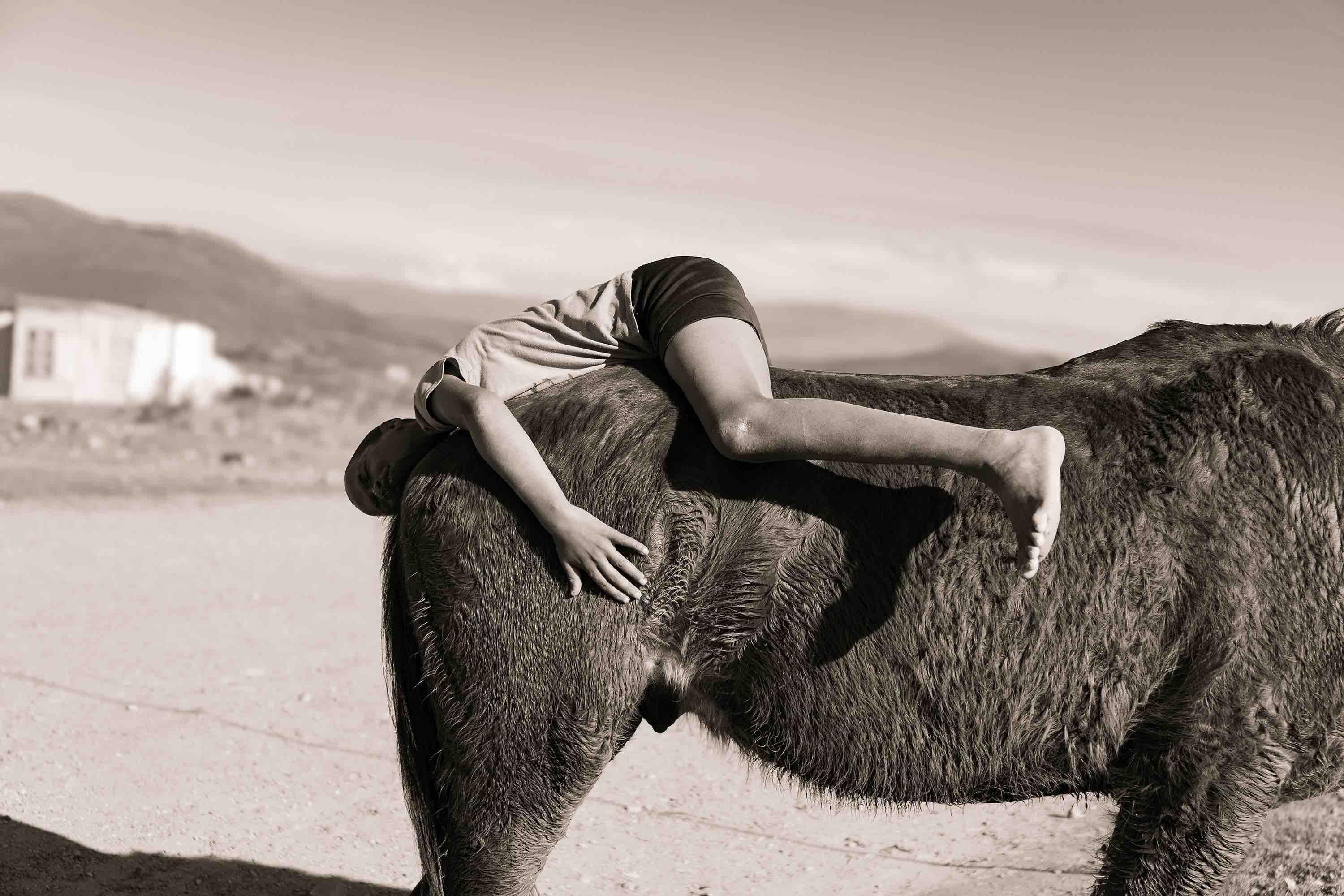

“The Valley of Grace and its communities have shown me the honest beauty in simplicity and connection to the land. The way people live here, so closely tied to nature and each other, has deeply influenced my work as an artist. There’s a sense of time moving differently, where life is measured not by the rush of the clock but by the rhythm of the seasons and the needs of the land. This slower pace has allowed me to immerse myself more fully in my photography, capturing moments that are often overlooked in the hustle of urban life. The humility and resilience of the people here have also taught me to approach my work with greater patience and sensitivity, understanding that every image carries a story that deserves to be told with respect and care”.

Horses have this deeply interwoven relationship with human beings that extends as far as 6000 years – it’s an ancient kinship, and studies are showing that this bond has physical and emotional benefits for both horses and humans. It’s a symbiotic relationship that can be measured, which is remarkable. Can you speak to what you’ve witnessed regarding this, the power of this relationship?

“The bond between horses and humans is extraordinary, and I’ve seen firsthand how powerful it can be. There’s a deep, almost unspoken understanding that forms between a person and their horse, built on trust, respect, and communication. This connection goes beyond mere companionship; it becomes a partnership where both the horse and the human benefit. Horses have a remarkable ability to sense human emotions and respond to them in ways that can be incredibly therapeutic. I’ve witnessed, as a rider and observer in the field, how spending time with horses can calm an anxious mind, bring comfort to those struggling with pain, and even help people process complex emotions.

Photography by Gabrielle Kannemeyer

In The Valley of Grace the community’s horses are certainly their mirrors. Most days I take very few images and spend more time watching the riders and their horses in awe. Their mastery over riding and the horses immense trust in them is truly something to behold. My goal while hanging out with these phenomenal riders is to capture moments that represent the bravery and beauty they exude together.”

What would you like people to know and understand about horse communities in South Africa?

“Horse communities in South Africa are vibrant, diverse, and deeply rooted in tradition. There are extremely dedicated, loving and talented equestrians in every corner of this country and their relationships with their horses are distinctly unique. Exploring these communities is a fascinating window into all of our similarities and differences through our shared love of the world of horses.

However, there are also communities that face challenges, particularly in rural areas where resources are scarce, and opportunities for growth and development are limited. I want people to understand that these communities are not just about the love of horses, but also about resilience, culture, and identity. The bond that people have with their horses is often a reflection of their connection to their land, their history, and each other. These communities play a vital role in preserving the heritage of South Africa. By understanding and valuing these strong and dignified culture-rich communities, we can help ensure that they continue to flourish for generations to come”.

On a technical level, how has it been to shoot horses – of course, guided by their ‘human’ in terms of stillness and patience, nevertheless, it’s an animal. How has this differed to you than working just with human beings as your subject?

“Taking photos of horses and kids is challenging for sure. Horses are really expressive animals, but capturing that expression requires a great deal of patience and understanding of their behaviour. They have their own personalities, moods, and responses to their environment, which means that as a photographer, I have to be very adaptable. It’s about finding the right moment when the horse is calm, comfortable, and connected with its human companion. Same can be said for kids! In front of the camera, kids are just small human-shaped horses.

I’m also working as a documentarian most of the time and that requires me to step away from the world I know best (fashion and controlled world building). So there’s a huge learning curve for me.

Working with horses also demands a heightened awareness of safety and movement. Horses are really big and their movements can be unpredictable. So I need to stay alert while being attuned to the horse’s body language but I think being a horse girly helps me here. I’m aware of horse behaviour. Technically, it also means being ready to capture a fleeting moment, which can be challenging but also incredibly rewarding when you get it right.

Taking documentary photos is like carrying two heavy bags all the time – one weighted with the remorse of missing photo opportunities and the other brimming with gratitude for the privilege of presence and the profound connection to life’s unfolding narrative.

Ultimately, photographing kids, horses and high pressure show environments has taught me to be more present and responsive to the moment which is a really useful skill to hone as a photographer”.

What else could you share with us about this work?

“Currently, I’m teaching photography to over 30 young riders. I’ve been providing them with disposable cameras to document their lives and share their stories. Cape Film Supply has generously been processing and scanning all of the young riders’ images, and ORMS has kindly offered a discounted rate for printing their photos.

In these access-limited small towns, cameras, and printed photos are quite hard to come by. A key part of the project focuses on equipping these young riders with the tools they need to create their own archives or photo memory banks of their wonderfully rich lives , preserving their stories and experiences for the future.

I am selling a handful of special prints to fund the work I’m doing in the valley.

I’d really appreciate it if you could check it out! Also, I’m open to making prints in other sizes, just give shouts if interested at all!”

Support this project and shop Gabrielle’s prints HERE

Photography by Gabrielle Kannemeyer

Written by Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za