“To exist humanly, is to name the world, to change it. Once named, the world in its turn reappears to the namers as a problem and requires of them a new naming. Human beings are not built in silence, but in word, in work, in action-reflection.” – Paulo Freire

Southern Guild opens its new gallery in Los Angeles with a dual presentation: Mother Tongues, a group exhibition featuring 25 artists from the African continent, and Indyebo yakwaNtu (Black Bounty), a solo show by South African sculptor Zizipho Poswa.

Mother Tongues, a group exhibition

The term ‘mother tongue’ refers not only to the first language of acquisition, but the first with regard to its importance and the speaker’s ability to master its linguistic and communicative aspects. One’s mother tongue is not only how a person positions themselves to the world, but how they position themselves in the world. Like the body, it is a border – a place of contact and confluence, an intersection of negotiations.

The expansion of Southern Guild into California is not unprecedented. In the late 1960s, a group of artists left South Africa in the wake of the Sharpeville Massacre, mass bannings and the censorship of political parties and cultural workers, eventually establishing a contact point for the interchange of knowledge and meaning between South Africa and California.

Southern Guilds positions itself at the later trajectory of this artistic migration. Having willed the promises of the future into the now with his cover of The Mamas and Papas hit California Dreaming, it is in Los Angeles where Hugh Masekela, arguably one of the continent’s most renowned cultural exports, establishes a home for Afro sounds as an imprint of Motown Records. Where Letta Mbulu lays a vocal track on Michael Jackson’s Liberian Girl. Where the Roots soundtrack is produced with several South African musicians. It is here where another touchpoint emerges. A point of contact, a border. Porous and primed for the osmosis of different kinds of “mother tongues” and emergent vernaculars.

With this inaugural exhibition, Southern Guild hopes to open a new chapter of exchange. The show occupies multiple contact zones, moving between visible surfaces and interior states. Taking a multi-generational and transnational lens, it charts the way in which language and pedagogy is channelled into diverse forms of expression. Though the nature of this enquiry requires a singular focus, its sights must be multiple.

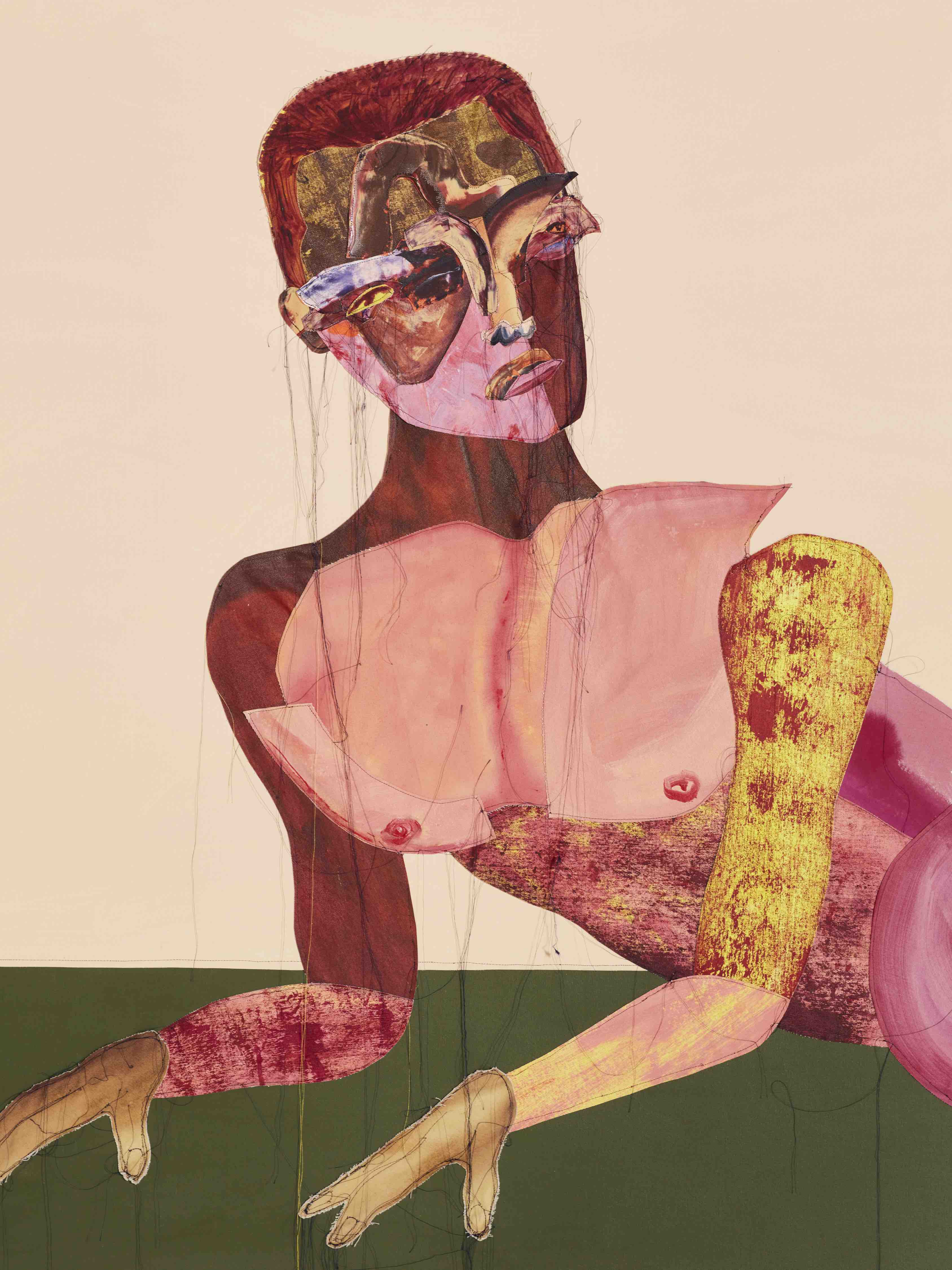

Award-winning visual activist Zanele Muholi’s stark portrait Siyikhokonke speaks to this heterogeneity. They position themselves on either end of the lens, both captured and capturer. Participant and image-maker. Black and white, the work presents itself in contrasts and dichotomy but the title – loosely translated as “we are everything” – speaks to the multiplicity of being. Of everything being everywhere, all at once. Poly, not polar. Where Muholi locates themselves in the frame, the singular standing for many, Jody Paulsen’s portraits are many made one. A corporeal collage, his nude portraiture consists of limbs and ligaments in inked fabric and thread, stitched and spliced together creating a vulnerable, intimate personhood.

Paulsen’s figures present themselves for steady observation, but similar to emerging artist Jozua Gerrard’s masked figures painted in enamel on glass or Justine Mahoney’s collage sculptures, they trouble the act of looking. Here, seeing offers no comfort of context but rather entry points to possibilities of (mis)understanding. This is the lexicon. Fragmented narratives made whole in the mind of the viewer. In Tony Gum’s performative portraits, the body is a continent burdened with stories.

Manyaku Mashilo’s artistic foundation lies in the historically charged realm of portraiture, yet she considers her paintings to be abstractions. Mashilo’s artistic practice serves as a means of sense- making; her canvases function as liminal spaces where she synthesises elements of her religious upbringing, ancestral heritage, a blend of real and imagined myths, folklore, science fiction, music, and sourced archival photographic images. Nigerian-Canadian artist Oluseye also works in the “in-between”, re-animating found objects and detritus collected from his trans-Atlantic travels into talismans akin to those that Africans carried for protection on their forced and voluntary journeys across the ocean. By incorporating Yoruba cultural references, he blends the ancestral with the contemporary, rejecting binary distinctions between tradition and modernity, physical and spiritual realms, past and future, and old and new.

For renowned South African ceramicist Andile Dyalvane, the connection to home comes through his medium – clay or “umhlaba” (mother earth) – a life-force that tethers him to the rural village of his birth. As a medium for storytelling, it is also an essential energetic link to his past, present and future.

Zanele Muholi ‘Thatha konke I’ Sheraton Hotel, Brooklyn, 2019.

Jody Paulsen ‘Tomorrow Man’ 2023, photographed by Hayden Phipps, Southern Guild.

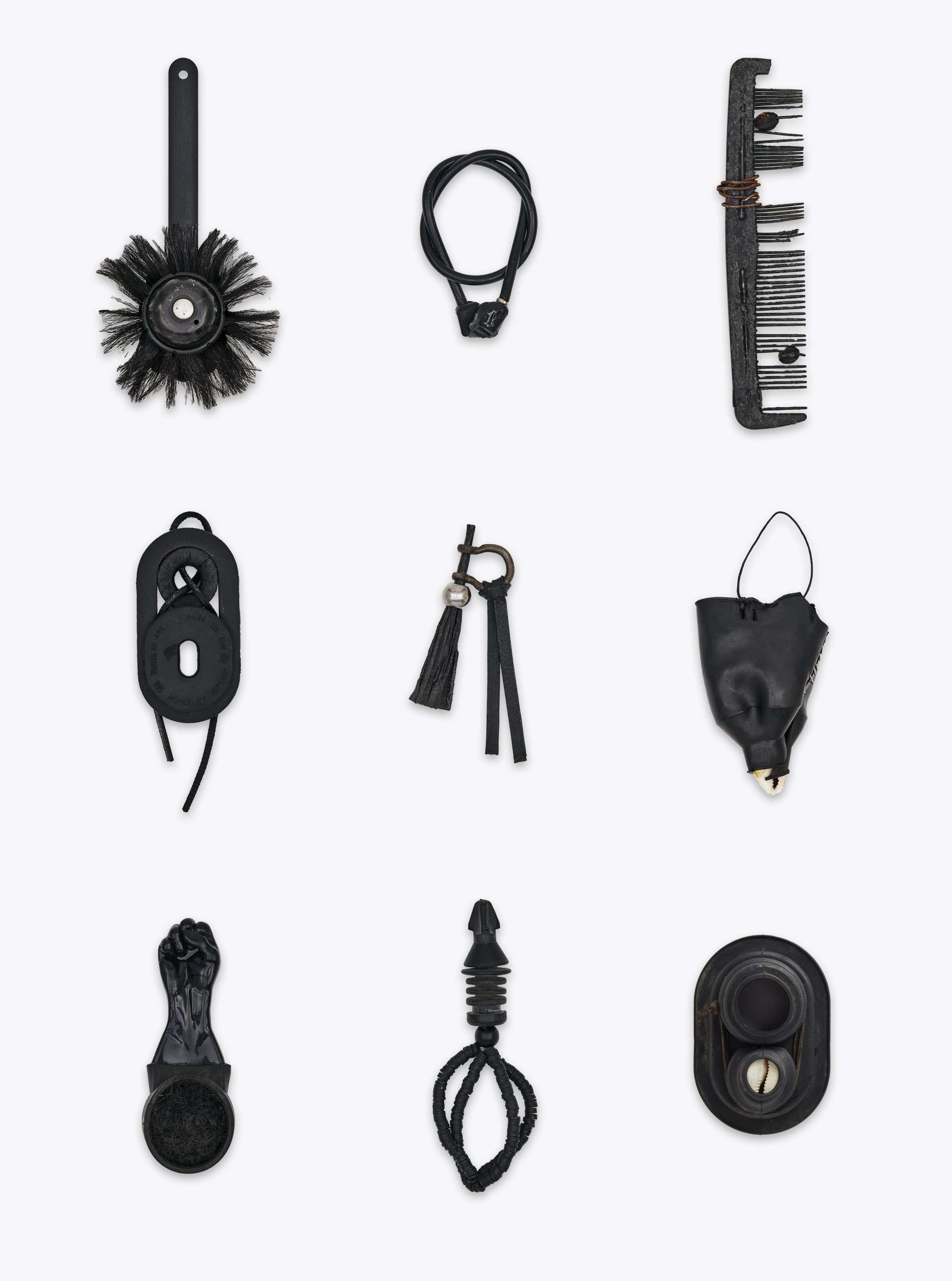

Oluseye Eminado ‘Reunion’, photographed by Hayden Phipps, Southern Guild.

Andile Dyalvane ‘Nkcokocha’, photographed by Justin Patrick, Southern Guild.

Patrick Bongoy’s rubber wall hangings transmute the inert and impermeable material – a harvest heavy with colonial-era exploitation – into tapestries alive with movement and blooming forms. The Congolese artist’s studio operates like a factory in reverse, transforming stockpiles of rubber inner tubes into dense textiles by stripping, cutting, weaving, looping and sewing the material.

Repetitive labour is also the methodology of two other artists working in sculptural assemblage: Dominique Zinkpè, from Benin, whose primary material comprises hundreds of intricately carved Ibéji dolls, and South African Usha Seejarim, who employs everyday objects such as wooden clothes pegs to explore the value of domestic labour and rituals of maintenance and care.

Rich Mnisi’s Nwa-Mulamula’s Chaise, modelled on the shape of his great grandmother’s reclining body, takes its fluidity from organic curves, simultaneously revealing and concealing. Working primarily as a story-teller, Mnisi mines the personal and familial in a manner that turns intimacy into praxis and aesthetic.

Nigerian-British ceramicist Ranti Bam’s terracotta torso vessels abstract and stretch what it means to hold language. Enthralled by etymology, Bam’s creative endeavours are a means of communication. “We express ourselves to encapsulate our experiences in a tangible form, to share,” she reflects.

This intimacy is echoed in Luyanda Zindela’s painstakingly sketched drawings, largely drawn from a series titled Abangani bami – izithombe zami (my friends – my images). Here, the artist posits the idea of close friendships as metaphorical mark-making processes. Drawn to the traditional, laborious nature of cross-hatching, each juncture of line meeting line is an imprint of tenderness, of self.

Chaos/complexity theorists argue that the development and learning of language is not a straight-forward process. Rather, like Africa-centred understandings of time, language is a sloshing, not an ordering. In Kamyar Bineshtarigh’s large-scale paintings, his interest in calligraphy and script makes room for abstraction; lines become blots and language is layered in such a way that its stratifications, if they exist, are imperceptible. Words, histories are things that sit on top of each other.

Languages of the intimate vernacular, or, our mother tongues play an interesting role in how we observe and keep rituals of memory and meaning. Ingrained with its own bureaucracies, rules of engagement honed over time, over place. The personal is political, but the vernacular creates its own politic, veiled in the familial, the traditional, the rituals of the mundane and the magical.

Ranti Bam ‘Fife’ 2023, photographed by Hayden Phipps, Southern Guild.

Kamyar Bineshtarigh, ‘Panel Beaters Gate’, 2023, photographed by Hayden Phipps, Southern Guild.

Rich Mnisi, ‘Nwa-Mulamula’s Chaise in Sheepskin’, 2019, photographed by Hayden Phipps, Southern Guild.

Indyebo yakwaNtu (Black Bounty), a solo exhibition by Zizipho Poswa

Indyebo yakwaNtu is Poswa’s most ambitious technical undertaking to date, comprising five colossal ceramic and bronze sculptures reaching heights of over 8 feet tall. The clay bodies were produced during her summer-long residency at the Center for Contemporary Ceramics (CCC) at California State University Long Beach, where Poswa had access to the centre’s immense kilns. She worked under the guidance and apprenticeship of renowned American ceramic artist Tony Marsh, co-founder and inaugural director of the CCC, which functions as an influential hub for expanded discourse and advanced creative production in the West Coast ceramics community. Poswa joins the more than 200 artists from 20 countries who have been invited guests at the centre, including Magdalene Odundo, Simone Leigh, Akio Takamori, and Morten Løbner Espersen.

In this new body of work, Poswa consciously upscales objects of African beautification and ritual. Precious metal jewellery, beadwork, hair combs and pins made by master artisans across the continent are emulated as bronze-cast elements resting atop vast ceramic silos, revering and immortalising the valued positions these amulets hold.

Translated from Xhosa, “indyebo” literally refers to material riches but more broadly encompasses the cultural, economic, intellectual and spiritual wealth of Africans. “Ntu” is the spirit that defines and gives impetus – an embodiment of the identity, consciousness and life purposes of African beings. Indyebo yakwaNtu is, therefore, a fulfilment of Poswa’s ancestral mission to celebrate both the natural and self-producing beauty of the continent.

Her approach in this body of work is distinctly Pan-African: “Drawing on Africa’s own mineral wealth, her people have created an immeasurable creative collection from which African men and women adorn themselves, resulting in a language of objects that has come to shape our identity,” Poswa says.

With their bronze crowns, this series of sculptures stands as a praise song to early African civilisations. Poswa traces the traditional healing customs, polytheistic practices and cosmological knowledge of her amaXhosa culture to its Kemetic heritage. The influence of the Nubian kingdom – rich in gold, ivory and ebony – spread along the Nile from Egypt to Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda and Ethiopia and through trade routes, human migration and nomadic cultures to the Swahili civilisation in Mozambique, the Sahara of Northern Africa, and the Southern African region where Poswa finds her home.

Zizipho Poswa photographed by Peyton Fulford and Southern Guild.

Zizipho Poswa’s Process, 2023 photographed by Elon Schoenholz and Southern Guild.

In Akan, a large square crest with filigree pattern accentuates the beauty of the lapis lazuli- blue clay body beneath it. Modelled on a bead adornment worn by the Asantehemaa (the queen mother of the Asante people), this piece celebrates the authoritative positions women held in the Akan Kingdom’s dual-gender system of chieftaincy. Asante queen mothers commanded soldiers in war, engaged in politics, occupied chiefs’ stools, played senior advisory roles and resolved disputes in courts.

In another work, the Lobi people who settled in Burkina Faso are recalled through a majestic bronze reproduction of an ornate brass hairpin design. In a piece titled Fulani, the earrings traditionally worn by the Fulani women in West Africa, northern regions of Central Africa, South Sudan, Sudan, and near the Red Sea coast are emulated through sensuously enveloping swathes of bronze. Historically, these finely forged gold earrings served as a symbol of social standing, with their size indicating societal status or economic wealth.

Elsewhere, a “cisakulo” comb of the Chokwe from what is now Mozambique depicts an Ngungu bird, a symbol of strong leadership. Closer to home, Poswa references the Xhosa “isacholo” bracelet in an arc of four large spheres representing the white beads these are made of. This work “celebrates the heritage of the people who birthed me,” explains Poswa. Understood to hold healing properties, the isacholo is worn mainly by elderly Xhosa women as it is believed to alleviate blood circulation and bone-related ailments. In Xhosa culture, white beads symbolise purity, clarity and mediation. Today, they are still used as spiritual offerings worn by “amagqirha”, divine traditional healers, when communicating with the ancestors. In Poswa’s ceramic totem, beautification extends beyond the decorative to become a tool for spiritual resonance.

Often passed through generations of women as family heirlooms, jewelry’s importance surpasses its material value to encompass cultural, geographic, sentimental and matrilineal significance. Indyebo yakwaNtu extends Poswa’s artistic practice of homage to crowns worn by African women, which have previously included braided hairstyles and loads of water, firewood and produce carried on the heads of women across the rural Eastern Cape. These monumental works revel in the transformative power of beauty – following on from Poswa’s acclaimed series Umthwalo (isiXhosa word for ‘load’), iLobola (customary dowry) and uBuhle boKhokho (Beauty of Our Ancestors) – honouring the community of women who raised her, while looking elsewhere to the continent for inspirational offerings.

“I am inspired by conscious design,” Poswa says, “Indyebo yakwaNtu is therefore an anthropological excavation that weaves together the socio-cultural and spiritual elements that underpin African creation.”

ABOUT ZIZIPHO POSWA

Zizipho Poswa is a Cape Town-based artist whose large-scale, hand-coiled sculptures are bold declarations of African womanhood. Born in 1979 in the town of Mthatha, Poswa was raised in the nearby village of Holela in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. She graduated from the Cape Peninsula University of Technology with a degree in surface design and in 2005, she and fellow ceramicist Andile Dyalvane opened their studio, Imiso (meaning “tomorrow”) Ceramics. Since 2017, Poswa’s oeuvre for Southern Guild has straddled figuration and abstraction, employing an intuitive vocabulary of form, colour and texture. Her work is a deep invocation of her personal journey and an homage to the spiritual traditions and matriarchal stewardship of her Xhosa culture. She has held three solo exhibitions to date: iLobola (2021) and uBuhle boKhokho (2022), both at Southern Guild in Cape Town, and iiNtsika zeSizwe at Galerie56 in New York. Poswa’s work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art and the LOEWE Foundation, as well as important private and corporate collections around the world. She has taken part in group exhibitions at Marian Ibrahim (Chicago), Jeffrey Deitch Gallery (Los Angeles), the Indian Ocean Craft Triennial (Perth), and other galleries in New York, Paris, Hamburg and Liverpool.

ABOUT SOUTHERN GUILD

Established in 2008 by Trevyn and Julian McGowan, Southern Guild represents contemporary artists from Africa and its diaspora. With a focus on Africa’s rich tradition of utilitarian and ritualistic art, the gallery’s programme furthers the continent’s contribution to global art movements. Southern Guild’s artists explore the preservation of culture, spirituality, identity, ancestral knowledge, and ecology within our current landscape. Their work has been acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, LACMA, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pérez Art Museum, Mint Museum, Harn Museum, Denver Art Museum, Vitra Museum, Design Museum Gent and National Gallery of Victoria. Since 2018, the gallery has collaborated with BMW South Africa on a year-round programme of meaningful activations that promote artist development and propel their careers. Located in Cape Town, Southern Guild will expand internationally with a 5,000 sqft space opening in Melrose Hill, Los Angeles in February 2024.

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za