Tatenda Chidora’s biographical epitaph on Instagram reads, ‘I believe in AFRICANISM’. This conviction is palpable in Tatenda’s many bodies of work; landscapes, sceneries and the poetics of people materialise through his photography in the way that one would imagine from a visual doctrine, descriptive of this precise time on the continent. If someone were to ask me, what does Africa look like right now, ontologically or sartorially? I would point them to Tatenda’s work, and I would tell them that I believe he is one of the eminent visual architects in Southern Africa.

Tatenda’s path to image-making is one steeped in alignment of both space and time. The medium of photography wasn’t always so clear, until it crystallised itself front and centre through his love of magazine collecting. As Tatenda explains, “I’m Zimbabwean, and so I was born and bred there. I moved to South Africa in 2008, due to economic situations, and I was trying to find a place where I could study. Initially, I was supposed to go to culinary school – but I ended up working instead. I’ve loved magazines all my life, and I’ve collected them for a long time. My favourite was one small seed, which was such a beautiful, independent zine. I think that habit, of pouring over images in magazines, prompted me to pursue photography. I thought, if I could buy a camera, perhaps I could give this a try? So, when the opportunity came for me to study, I decided it had to be photography. I feel like I was pulled into visual arts in that way; I had to realise it was meant to be photography, and everything happened from there.” One of the most ineffable aspects to Tatenda’s work is his technical mastery over light. In a layman’s sense, some may not realise quite the potency that the refractional or tonal nature of light is the greatest companion of any photographer. Hence, the practice is founded on the ability to weave light almost as its own characters in images; Tatenda achieves this with dizzying effect. I learned that as a long-distance marathon runner, it is quite literally the light of our earth, of the dawn and dusk, that Tatenda has employed as his teacher, “I am always in spaces where I see a sunrise, or a see a sunset – and sometimes I even find myself running in the peak of the day, especially when I’m training for marathons. It is a beautiful analysis of light, and most of my subjects are Black – and depending on the type of day, the skin has the most incredible reaction. Black skin and the quality of light interact together. I find there is a temperature that can be translated onto skin depending on the time of day, and that is light’s domain. It really helps me to create my images in a deeper, more textured way. Observing light is one of my most important tools, so much so that I will take mental notes on a run about the light, the time that it was and the conditions of the weather. Then, when I have an idea, I can seek out those conditions, and experiment. One of my favourite things is how the sky, or clouds, bounces in the foregrounds and brings illumination to the skin or bodies of the people that I photograph.” Tatenda’s work is a synergy of light, texture, skin and colour; this alchemy is definitive of Africanism, and the accentuation of that inarticulable magic that governs the continent.

Tatenda Chidora, CAPTURED II.

Tatenda Chidora, Un Ordinary.

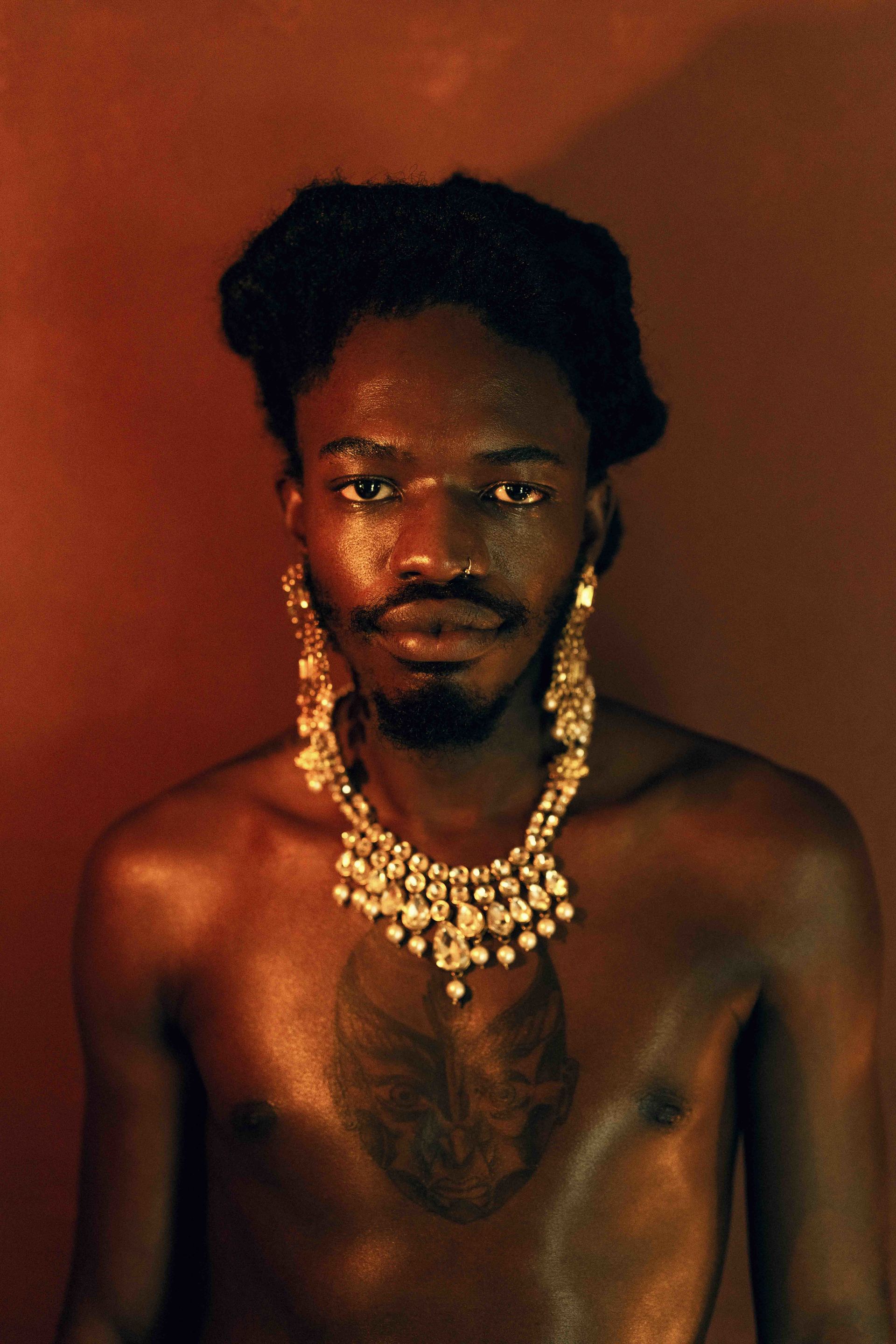

Regarding Black photographic portraiture and African photography, Tatenda has felt a responsibility to communicate what he knows best and most intimately, “I always say, if you stay in New York as a New Yorker, you have the best perspective and most authentic point of view, so you can translate New York stories the most accurately and the most honestly, because you inhabit the space day and night. For me, it’s the same thing as an African photographer. I have a responsibility to tell African stories accurately. I know how it is, and how to interact and interpret scenes and people. Also, to change the narrative that has been placed over African photography is critical. Whenever I photograph, I am in a space of celebration; I am celebrating Blackness, and the beauty that lies in being Black and in being African. I remember how difficult it was in university to find full archives or works by African photographers, and that was awful – I wanted to bring out a more conceptual, artistic viewpoint of Africa. Even in the grungy-ness, or the textures of everyday life, within the changing tides of the continent- there is so much beauty and so much richness to capture.” Almost everyone I speak to with the creative space is affirming this sense of an African renaissance; it’s happening, and it’s wildly energising. Even against the backdrops of uncertainty, of socio-economic difficulties, the sentiment sweeping across varying artistic disciplines is one of immense hope and foresight for the future. I ask Tatenda his thoughts on this, to which he says “it’s really quite exciting. Before, there was this narrative that people had to come to Africa, and ‘see for themselves’, consuming or making assumptions – and then they go back home and describe their stories or narratives. What gets lost, even not just distorted, is those stories and experiences of Africa that are not available to everyone. Now, the world is listening to African human beings. We are being asked to tell our stories, while refusing to have our stories told on our behalf. We are seeing this across fashion, art, music and so on – and we are showing them. It is the greatest time to be alive as an African artist, because everywhere you go; people want to know, they are curious about what it means to be African. This is a time where Africa is being represented on the world stage directly from the source, from African people themselves.”

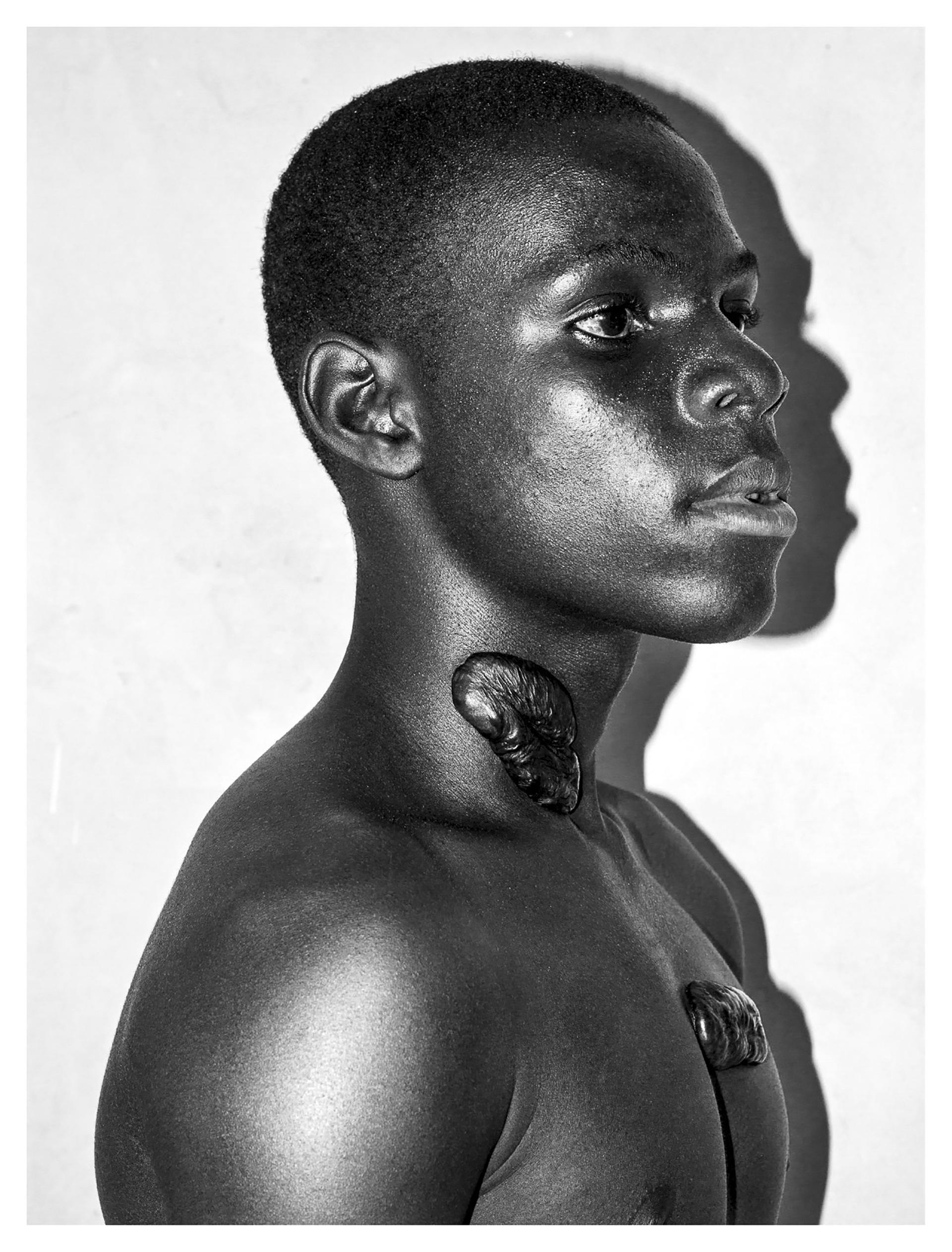

Tatenda Chidora, METAMORPHOSIS I.

Tatenda Chidora, METAMORPHOSIS II.

Tatenda Chidora, METAMORPHOSIS III.

Last year, I picked up a copy of Dazed Magazine at Exclusive Books – a moment that comes around spontaneously, whenever we seem to get a shipment of publications other than the usual suspects of Vogue and Vanity Fair. In it, a feature spread with musician, artist and healer Desire Marea contained an essay interview by Nkgopoleng Moloi, and images by Tatenda with incredible styling by Nao Serati. Shot in KwaZulu Natal, Tatenda reflects on this experience, “that was quite a magical and challenging experience. The first day we were supposed to shoot, the floods in KZN started. So, we had imagined what we would do, we had understood our approach and came with all these beautiful garments. We couldn’t get to Desire’s hometown due to the floods. It was such a beautiful experience in the end though, and I don’t know anyone who could have embraced the forces of nature the way he did – I believe between his creativity and his spirituality, things came to be aligned, and in the midst of the powerful rains, we ended up capturing exactly the kind of mood and depth that you see in those images.” There, in the heart of KZN, the images revealed storm clouds in the background with Desire’s portrait centrally focused – or Desire finding stillness among a thick meadow, recently effulgent from the heaven’s rain. Tatenda speaks to the power of this collective story-telling across the continent, saying “As Africans, we have embraced our own identity. We are healing the idea of being either African American, or completely westernised and colonised. I have so much respect for artists, designers and so on – and they are on the stage in Europe, and they point back at the continent, and they are coming back home. There is this understanding that, well, if the world wants me – they can love me from my home, from my continent or country, you know? That’s so powerful, to be who we are, and to allow ourselves to do so.”

Desire x Dazed.

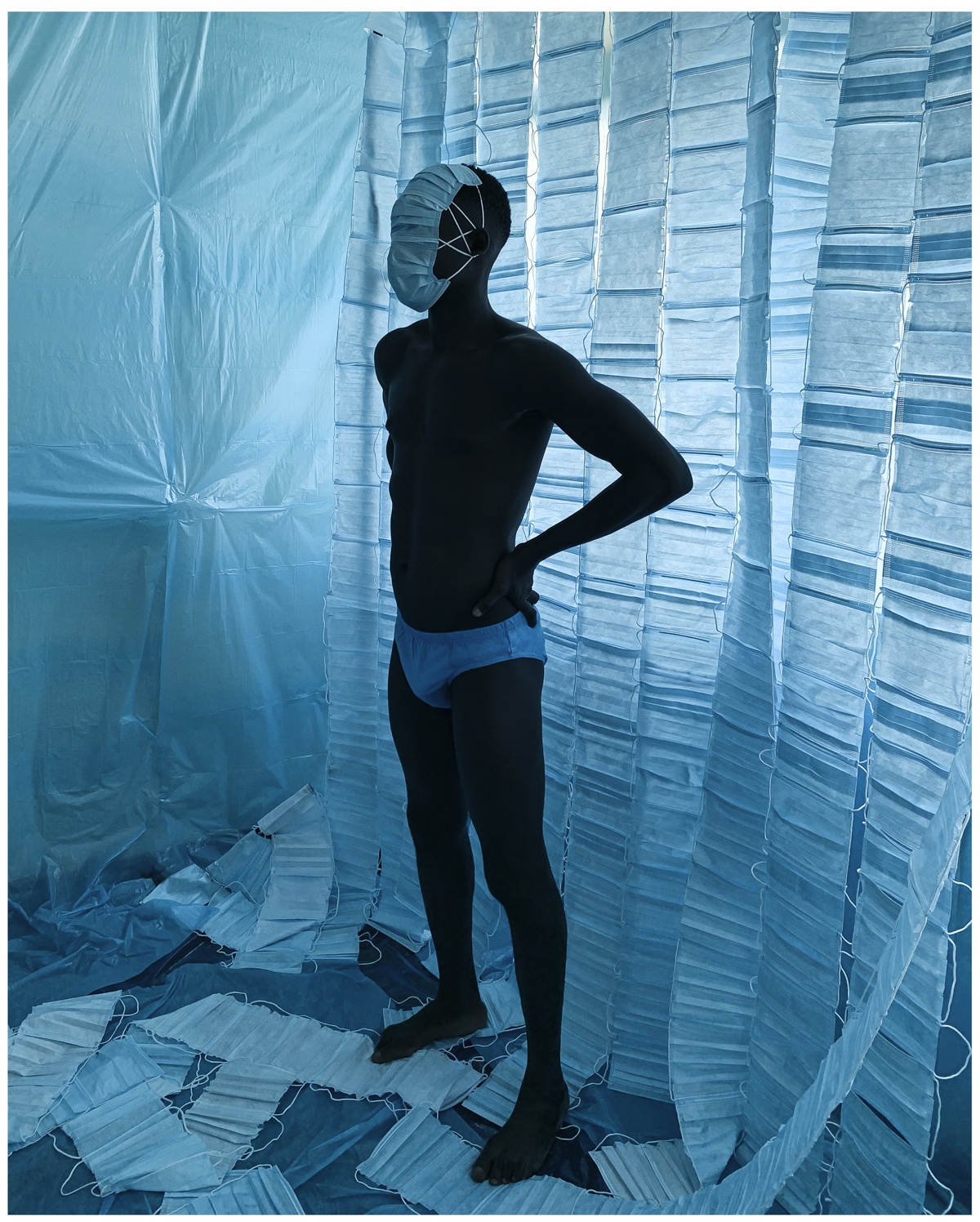

In the week of our conversation, it has been revealed that Tatenda’s work ‘If Covid was a Colour’ has been announced as a winning series for the British Journal of Photography’s ‘Portrait of Humanity, Volume 5’. The colour, to Tatenda, is a cobalt blue captured across varying models, with one in particular featuring stylised surgical gloves, replicating the spiked characteristic of the virus – but more interestingly, it reads as an avant garde head-piece. Tatenda says, “I remember reading the British Journal of Photography when I was in university. The curation is really beautiful, and they really try to broaden out across the world, and every Sunday they bring out ‘Sunday’s Inspiration’. I submitted my body of work last year, and I wanted to communicate a different point of view of the pandemic. There are many documentary images of that time, which are very real, harsh and factual of what we went through – and so this series was a way to celebrate humanity. We really stood up and above the pandemic as humankind. It’s such an honour to see my work recognised in this way.” With the thoughtfulness and tenderness of a visionary, I know that we will continue to see Tatenda’s work take shape in the world; his future is saturated by all the illumination of light, and beyond.

Tatenda Chidora, If Covid was a Colour.

Tatenda Chidora, Self Isolation I & II.

Written by: Holly Beaton