Fashion is often spoken about in terms of aesthetics—what is beautiful, what is trending, what is wearable. If we have any kind of proclivity towards fashion, we are constantly observing an endless onslaught campaigns, editorials — fashion weeks — street style imagery, red carpets: making judgements, feeling emotions and making estimations about what the wearer or designer is attempting to convey. We also know, each of us, instinctively what it is that we like. Often it’s at first glance, and somehow it feels simply intuitive to our taste and sense of style.

Sometimes, we can study something long enough for it to grow on us and other times, we can change our minds about a look if we are provided with the context in which it was worn. This is the intuitive nature of the eye— the ability to perceive balance, proportion, and intention in design before the mind consciously registers it. And honestly, it’s something that needs to be developed over time. If you went back in time to ask 16 year old Holly what chic meant; she’d say a crop top and high-waisted jeans with Doc Martens. That is to say, our eye for design is as impervious to our own evolution. It requires exposure and experience; and hopefully, this Chapter will dose that just a bit, for you.

Thebe Magugu shot by Pieter Hugo, Styled by Chloe Andrea Welgemoed, via @thebemagugu IG

Damian for Rick Owens FW24, via @rickowensonline IG

Interlude as a fashion column was initially born from a desire to voice somewhat educational, fashion-nerdy style writings about this untenable creative medium that we so love — Chapter 25 is a return to that first sentiment, as we look at the visual language that besieges fashion’s deeper structural foundation: the architecture of clothing— as we figure out if, simply through a technical eye, we can match our instinctive ‘yes’ or ‘no’s’ with some kind of critical understanding.

Every garment is a product of form, silhouette, and construction, all of which come together to convey the maker’s vision. In the same way that buildings stand as expressions of cultural and philosophical ideals, fashion is first and foremost a technical ability that uses cut, sewing, and tailoring to establish a distinct identity. I have often found myself getting lost in the show notes of designers: their post-mortem ideas of what the collection ended up becoming. It’s a skillset to look at a garment and derive meaning before ever hearing a word from its maker, and for the purposes of analysis, knowing exactly what we are looking at from a technique standpoint feels essential. Or haughty. Maybe a bit of both— and would it be a sartorial conversation if it wasn’t slightly snobbish?

Fashion designers use construction techniques to build an aesthetic world that extends beyond surface decoration. Every drape, dart, and seam is an intentional decision that influences both the emotional and intellectual resonance of a piece. Yes, it is that serious— or at least it can be.

Some designers engage with construction as a means of pure function, while others use it as a primary mode of storytelling, embedding layers of meaning into fabric and form. One of the most fundamental ways designers establish a distinct identity is through silhouette. Silhouette refers to the overall shape and outline of a garment—the way it frames the body and occupies space. The overall silhouette dictates proportions, movement, and structure, serving as the most immediate visual expression of a designer’s intent. It can determine, from a philosophical sense, how construction has been used to interact with the body, and how it can communicate, say, ideas of power, vulnerability, rebellion, or tradition. After all, clothing is ultimately about a relationship between body and material. I think of the exaggerated, armour-like tailoring of Alexander McQueen, for instance, that conveyed a sense of dominance and control, drawing from historical references while pushing the boundaries of contemporary craftsmanship. Lee’s precise cuts and sculptural structures evoked an almost mythical presence, reinforcing themes of strength, mortality, and transformation: while being entirely controversial and stained by his own personal cynicism, all at once.

Y-3 Atelier Gore-Tex Collection by Yohji Yamamoto, via @yohjiyamamotoofficial IG

Kristina Nagel Self-Portrait, via @rickowensonline IG

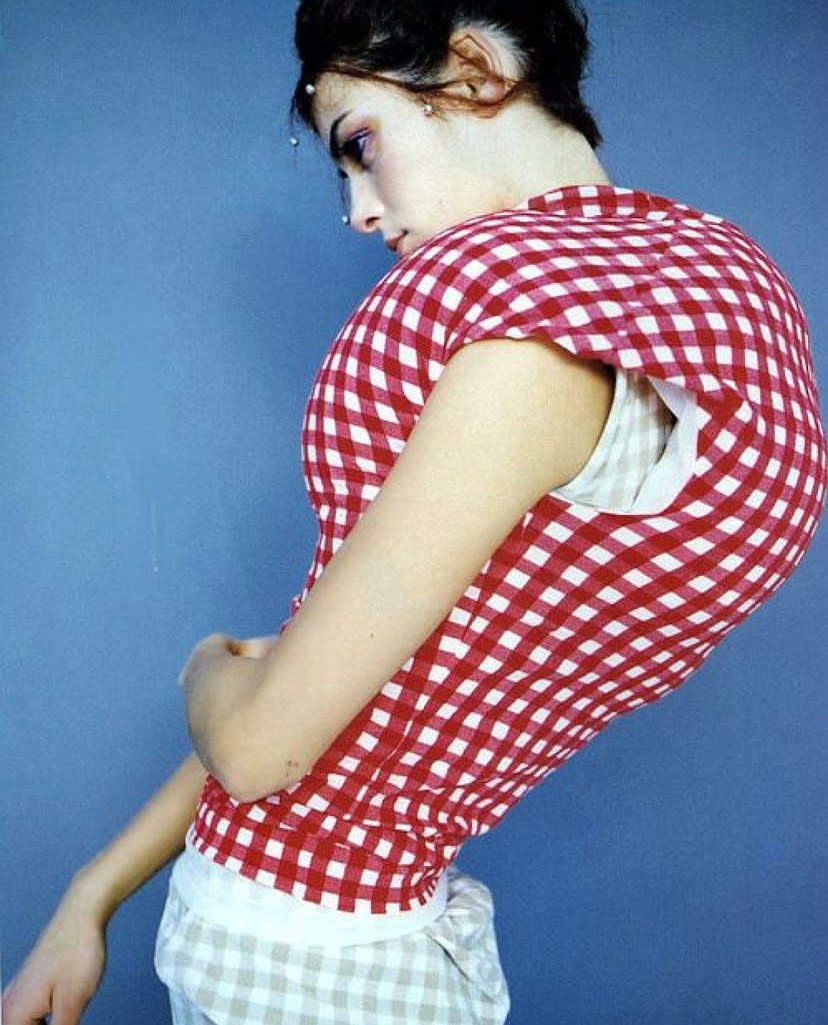

Few masters exist in fashion today that reside above Rei Kawakubo and her exploration of silhouette, through her label Comme des Garçons. Since the 1980s, Rei has consistently subverted conventional notions of the body itself. Fashion and aesthetics, for her, have little to do with creating beauty, and more to do with challenging the conventions of what makes us comfortable when we interpret beauty. Through radical deconstruction, and as an agent of the avant garde, Rei’s decades-long interplay of asymmetry, and unexpected volumes, have challenged the very definition of what clothing should do—whether it should flatter, conceal, or redefine the human form. Rei had critics up in arms when she showcased Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body (in 1997), which showed all manner of padded bulges that distorted the familiar female silhouette, creating shapes that resisted easy categorisation. It was a spectacle; loved and hated, simultaneously. Today, it remains one of the most powerful demonstrations of a woman’s confrontation with the feminine form in the context of luxury fashion.

In this way, silhouette can be an immediate signifier of a designer’s ethos; a visual shorthand for the narratives and ideologies embedded in their work. Whether reinforcing social structures or dismantling them, whether creating garments that empower or disrupt, fashion’s most compelling minds have understood that developing their own interplay of silhouette, supported by construction, is one of the most powerful tools for conveying a message.

Bias cutting and deconstruction are just a few examples of how technique acts as the throughline between an idea and arriving at a final, material form of what one is trying to say. Bias cutting, popularised by french fashion legend Madeleine Vionnet in the early 20th century, saw garments that cling and move fluidly with the body, producing a sense of sensuality and freedom— during a time when women had barely started showing their ankles without fear of judgement or harm.

Deconstruction, and the anti-fashion perspective proliferated by designers like Yohji Yamamoto and Martin Margiela, was an attempt to strip garments down to their raw elements, exposing seams, unfinished hems, and asymmetry as a commentary on imperfection and the transient nature of fashion. Maybe even fashion’s inherent meaninglessness. This is the area of construction that I find the most astounding— the way beauty can be cut from cloth, haphazardly and yet deeply intentionally.

Sindiso Khumalo AW22, shot by Xavier Vahed, via @sindisokhumalo IG

Rei Kawakubo’s distorted padding, SS97, ‘Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body’, via @eis.mag IG

Yohji Yamamoto’s work is often described as an act of controlled destruction; and if one wants to understand high command of technique, there is a near-total absence of colour and print in his work over the last 40 years. That’s how irrelevant they are to his practice—how little he relies on anything but construction to communicate. His garments reject traditional Western ideals of fit and proportion, embracing asymmetry, oversized draping, and a preference for black that emphasises form over embellishment. Coming up in Paris in the 1980s, during the Versace-sexy-glitterati era, Yohji exposed sensuality through exaggerated form to an audience that had yet to grapple with the art of layering; Yohji famously noted that “it meant something to me—the idea of a coat guarding and hiding a woman’s body. For me, a woman who is absorbed in her work, who does not care about gaining one’s favor, strong yet subtle at the same time, is essentially more seductive.” Through techniques such as exposed stitching, fabric layering, and the deliberate use of raw edges, Yohji’s work reconfigures the relationship between clothing and the body. His designs are architectural in their ability to create space around the body, shaping volume through negative space and movement rather than rigid structures.

In 1988, (my sartorial mother) Michèle Lamy hired her young, bright-eyed boyfriend, Rick Owens, as a patternmaker for a clothing line. So impressed by his talents, Michèle helped Rick launch his own label in 1994—and the rest is living, breathing, independent fashion history. Rick approaches construction with a sculptor’s hand, creating garments that balance brutality with elegance. Committed entirely to the punk attitudes of his youth, his use of draping and layering often results in a softened, almost ethereal take on minimalism; ever imbued with tones of harshness, and his impassioned cries for a more socially conscious and liberated world. A master of ‘basics’ (and impeccable fabrication instincts) Rick’s manipulation of bias cutting and soft draping lends his designs a futuristic quality; the never-ending architectural approach that governs his post-apocalyptic visions and reverence for the ancient. Few designers today are as willing to risk and dream to the degree that Rick does— to the point where sometimes even I find myself questioning his choices. Yes, I’m talking about the Cargoflares. Hectic.

From a South Africa perspective, construction is a key technique in developing a design language that forges our future, with a unique task of reconciling indigenous and western influences. Thebe Magugu, for example, is defined by sharp tailoring, thoughtful silhouettes (and layering), and an acute understanding of construction that merges strict, structured lines with softer, more fluid elements. Thebe’s attention to detail—whether through precise darts, layered panels, or pleated accents—has the unique role of rendering each piece he designs into an artifact of cultural history; the many incredible collections that reference South African heritage, from political iconography to familial narratives. This use of technical precision and deep cultural resonance positions Thebe’s work as both contemporary and archival— love-letters to what was, what should have been and what might be. In many ways, his approach speaks to a broader movement in South African fashion, as a way of encoding history and identity into fashion.

Sindiso Khumalo’s approach to construction is deeply intertwined with her use of textiles. Her voluminous, feminine silhouettes are often achieved through fabric manipulation techniques that reflect historical storytelling, and by incorporating hand-drawn prints, embroidery, and pleating, Khumalo crafts garments that carry personal and collective histories, particularly those of Black South African women; with references to historical dressing, as a process of reclamation.

Lukhanyo Mdingi’s work is a study in the precision of form. His collections emphasise craftsmanship, and his silhouettes often play with proportion, balancing structured elements with flowing, relaxed details that speak to an effortless refinement. By integrating artisanal techniques and motivated by deeply cultivated relationships with craftspeople on the continent, Lukhanyo’s work is grounded in a slow, intentional approach to fashion—one that respects both materiality and cultural lineage. With an LM garment, one is looking at something so enriched, that also appears ‘thrown on’; the imprint of an organic ease—rooted in a philosophy that values tactility and a connection to the land.

Fashion, like architecture, is an exercise in shaping space and constructing narratives through material and form. This is an endless study and one I remain in my infancy in terms of understanding, but I really believe if we can appreciate how form, silhouette, and construction convey design messages, we can be reminded of fashion’s deeper purpose: to build, to challenge, and to tell stories, amidst the onslaught and crashing dread of consumerism.

The next time you’re drawn to a garment, can you try to pinpoint three things about the way it’s constructed that you notice, and love?

Written by: Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za