With every swipe, a dopamine hit arises in our brain; and while the information and curated visuals feel nourishing, the endless consumption truly is not. It feels as though we are at a point in our digital adoption in which a return to the physical is inevitable. Of course, we’ve always been immersed in our own realities—but from the very real revival of supper clubs and journaling to the rising popularity of community gardening, pottery workshops, and even handwritten letters, a quiet resurgence of offline culture is gathering momentum. I’d hesitate to explain this as a whimsical return to the past or some purist rejection of technology—rather, this is a counterbalance, or a recalibration. Digital hygiene is as prescient as ever, and after years of acceleration into the virtual, many are feeling their way back to something more grounded.

The rise in digital fatigue is well documented. A 2024 report by the World Health Organization identified excessive screen time and ‘digital overstimulation’ as growing mental health concerns, particularly among younger generations. The average adult now spends more than seven hours a day engaging with screens, and for many, this is starting to feel less like connection and more like confinement. We are, it seems, reaching the limits of our digital absorption, and the promise of limitless access and perpetual efficiency is giving way to a growing sense of psychic clutter: the result being our fractured attention spans, algorithm-induced anxiety, and a creeping dissatisfaction that no amount of content can seem to cure us.

WGSN have been reporting on this shift through the lens of brand-building, framing it around the emerging emotional state they call ‘Witherwill’—a word coined by John Koenig, author of The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows. Defined as a longing to be free from responsibility, Witherwill is predicted to be a key consumer emotion and coping mechanism by 2027, as people increasingly grapple with pressure on multiple levels.

While this is, naturally, presented in the context of helping brands sell their products, it clarifies that our collective digital fatigue has become so widespread, so culturally significant, that even marketing strategies are now being shaped by our need to slow down.

Across cities and small towns alike, the desire for real-life engagement is manifesting in all sorts of ways. We see it in the return of supper clubs and communal dinners. We see it in the uptick of local workshop attendance—from floral arranging, to jewelry making, book clubs and more. We see it in the return of tactile pleasures like letter writing, bookbinding, or simply walking without headphones. As crazy as it sounds, I think one of my proudest achievements over the last few years has been to train myself to work without headphones and be totally present, daily, with my dog. This is to say; digital hygiene requires our self-motivating discipline, as tough or obvious as it may seem to achieve.

A compelling example of this shift recently played out on Bree Street in Cape Town. During March this year, the Young Urbanists initiated a bold experiment: the entire street was shut to vehicular traffic for every Sunday and turned into a pedestrian-only cultural hub. The goal was to see what might happen when space was reimagined for people, and critically, no commercial activities were permitted. Instead, activities included free bike rentals for kids, community blanket making sessions with The Maak, graffiti workshops with Brother Love Studio, chess clubs and even a silent book club, with people perched on the road all reading together.

This reclamation of public space for non-commodified community purposes proved what a slower, more connected urban life could look like. The Young Urbanists are a phenomenal space that challenges the enduring apartheid legacies shaping South African cities. Rooted in principles of economic, social, environmental, and spatial justice, the group empowers its members—across all disciplines and backgrounds—to become change agents in their fields. With a strong focus on inclusivity, the platform initiates critical conversations and imaginative solutions for building more equitable cities across the country.

The return to the offline is similar in the world of commerce and brand culture, it’s increasingly clear that physical experience still matters—and may, in fact, matter more than ever. I don’t know about you, but I’m increasingly reluctant to buy online; instead, I prefer to try on clothes in real time, or take the trip to meander stores than predict something will be fitting for my home, wardrobe or fridge through a screen.

To understand this impulse at a deeper level, cultural theory is ever my go-to. French philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality, developed in the 1980s, offers a prescient lens for the mood of this moment; as he argued that in late capitalist societies, signs and representations begin to replace reality itself. In the hyperreal, we no longer engage with the real world directly, instead we engage with simulations of it. Case in point as we fast-forward to today’s social media-driven culture, and Baudrillard’s ideas feel uncannily accurate. A dinner is rendered a photo opportunity, and ‘the self’ becomes a brand. The more time we spend in simulation—curated, flattened, algorithmically manipulated—the more we crave what the simulation will never deliver: texture, nuance, unpredictability and presence.

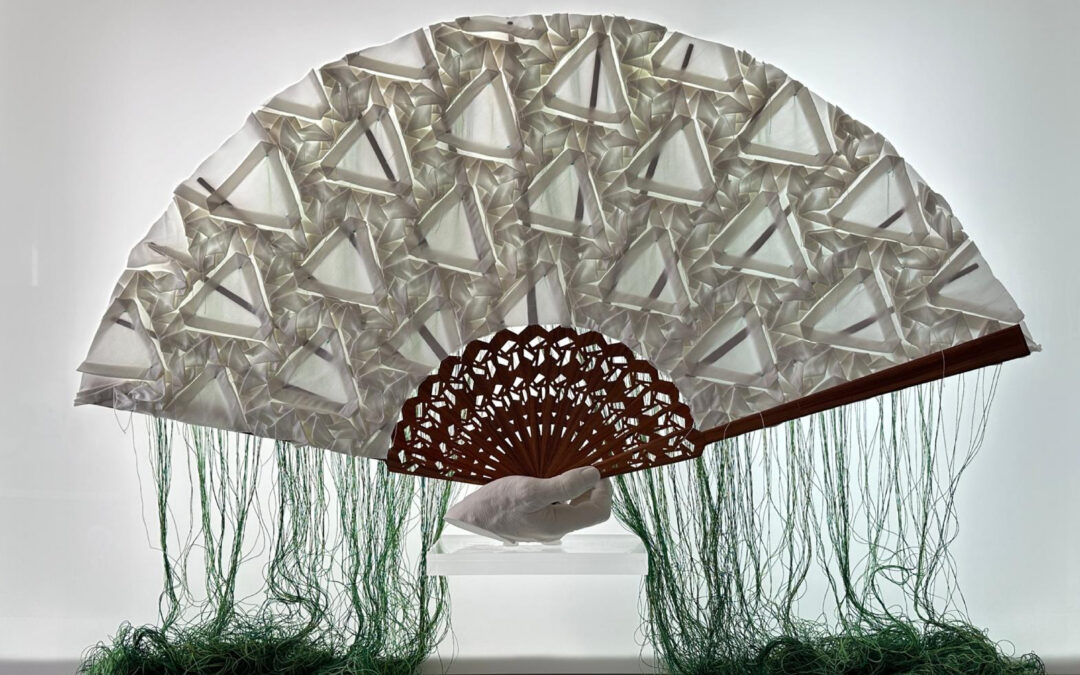

This is not to say that digital life has no value and the connectivity it offers remains transformative. There is no going back, however there is integration; we are beginning to see its limits, and to notice what our digital lives displaces. In some ways, the return to offline culture is a reckoning with the costs of relentless digitalism: attention fatigue, disembodiment, and the loss of shared, physical spaces. It is also a return to the idea that meaning is created through conversation, through making, through being together. The rise of “slow living” dovetails with these cultural shifts. Practices like journaling, analogue photography, gardening, and knitting are becoming central to how many people resist burnout and reclaim time. These activities slow us down and invite a deeper kind of attention, and in these slow-paced acts, efficiency is discarded; this is precisely the point.

Offline revival is also taking root in new business models that emphasise intentionality and connection over scale. Small-run magazines, zines, and locally hosted lectures and salons are vanguards of the future in the attention economy. At CEC, we’re committed to the long-form word and the art of the conversation, even amidst the waning attention spans of internet users. Artist-run spaces like The Drawing Room, or ceramics studios that offer monthly classes like Han Studio, are using skills transference as a form of community-kindling.

Even among Gen Z—a generation raised online—there’s a growing appetite for IRL engagement. Despite growing up digitally native, this generation is increasingly drawn to analogue tools and face-to-face experiences; perhaps because they know, better than anyone, how exhausting and performative the online self can become; the novelty having worn off by the time they’re forming their adult identities.

It’s easy to misread this moment as a cultural regression, or a nostalgic return to some imagined pre-digital purity. In reality, it’s a complex synthesis; we simply need to layer our lives with more balance, and this is the necessity of practicing digital hygiene as a function of our day to day.

Ultimately, the resurgence of offline culture is a hopeful sign. It suggests that, even amidst technological acceleration, our human need for connection and physicality persists. In the 21st century, we still get to inhabit a future that remembers the body, honours the senses, and values presence as a luxury— while being wildly connected to the broader world, and embedded in the complex swathes of culture and creation taking place all around the planet.

In this reality, being continually distracted is our challenge, while choosing to be present is our resistance. Every effort is required to find our place in this hybridised world.

What will you do with your time spent offline?

Written by Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za