I have been enamoured with Jabu Nadia Newman’s work for a long time – and it’s hard to believe that her groundbreaking web series, The Foxy Five was only five years ago in 2017. Written, produced and directed in a semi-autobiographical way by Jabu following the South African student’s uprising against the continued institutionalisation of colonialism and apartheid, the series exemplified the utmost necessity for black, female film-making and narrative building; with the synopsis centred on intersectional feminism and challenging stereotypes of black women as told through the dynamics of the five characters Unity Bond, Probably Plebs, Blaq Beauty, Femme Fetale and Womxn We. Referencing blaxploitation films, the Black Panthers and the aesthetics of the 70s, it had a cult-like response when it premiered in Cape Town, going on as a formidable artistic testimony for this political period; and remains a living, precursive archive of Jabu’s foundational intentions as a story-teller.

Since then, Jabu has been growing into an inimitable film-maker and director, independently and commercially. In speaking to her thematic considerations, she says “When I started I was very focused on current issues and political issues within South Africa. My work has since moved into a space of interrogating interpersonal relationships, particularly between women and women of colour. I am concerned with making work that is for the younger generation, and sharing some of my own awakenings that the political is intrinsically personal – it’s not this abstract, parallel construct that exists around us in government buildings – but rather seeing its direct presence in homes in South Africa. I think the most important stories that I am able to tell are the ones about my community; my family, my friends in the city that I am living in, or even the area and street.” While Jabu’s work draws on the framework of imagining realities, there is a decided presence that this statement speaks to – the sense of being here, where one is, and how one’s own life and experience is perhaps the most poignant story to be told – and can be told in a thousand ways.

Regarding Jabu’s aesthetic signatures, her work oscillates effortlessly between the dreamscapes of analog film and digital-driven tools, “I’ll always be informed by my roots as a photographer, with the view that my work should be able to exist in a gallery space. Even if you can’t understand the language or the story, I always intend for the lighting, colours, art direction and styling – the visual assertion of what I make – to convey the themes I am speaking to.” Making work predominantly on her own for her initial debut, Jabu is currently working more in the commercial space – something wholly necessary for story-telling and representation for a wider audience in South Africa. This has allowed her to focus her independent projects along a long-term trajectory towards longer short film formats and feature films. On working in commercial spaces, Jabu says “I really enjoy the challenge of working with someone else’s material – I think it’s contributed to my development in being able to balance my viewpoint with someone else’s. Collaborating with amazing teams in these experiences is incredible – the collaborative nature of being on larger sets, to smaller sets, has a special energy for anyone committed to this industry. I am learning to tell a story in a minute or thirty seconds – it’s so difficult, but so satisfying when it comes through. In South Africa, all creatives are doing some type of commercial work – it’s our bread and butter. I am hoping we will start to see a stronger connection between the creative vision of independent voices creating commercial work, and the corporate briefs that tend to demand exactly how something should be.”

Jabu has travelled a lot through her work, and has a special reverence for Paris – going back and back forth over the last few years, “Travelling is super interesting, and whenever I do – I wish every South African woman could experience what it’s like to walk around at night, or take the train and feel super safe. I have hiked up mountains alone when I’ve travelled. Going to a different city and getting lost has been critical for me, and I really like Paris because there is a strong African diasporic presence – creatives from across the continent who bring Paris to its fullness in art, film, fashion and music etc. It’s amazing to witness.” In terms of Jabu’s feelings about Africa and the richness of story-telling, she says ‘’I feel like we are moving into a much more global space, which is giving us a much wider audience. Studios like Amazon and Netflix coming here is great – but our cinematic roots are inherently underground or avant garde, whether it’s Ethiopian films, or Moroccan and Tunisian films – and ours here in South Africa – and I think that needs to remain. The dream, I suppose, is to continue with the commercial interest, but for funding of that scope to be dispersed across the array of genres that truly temper African narratives.” Although it’s slowly occurring for South African film-makers to hold viable careers, the issue of funding and infrastructure pervades almost all conversations I have with creatives from various disciplines. This topic can be exhausting, but it has to continue; the fight has to continue for valuing the vision and talent of South African artists.

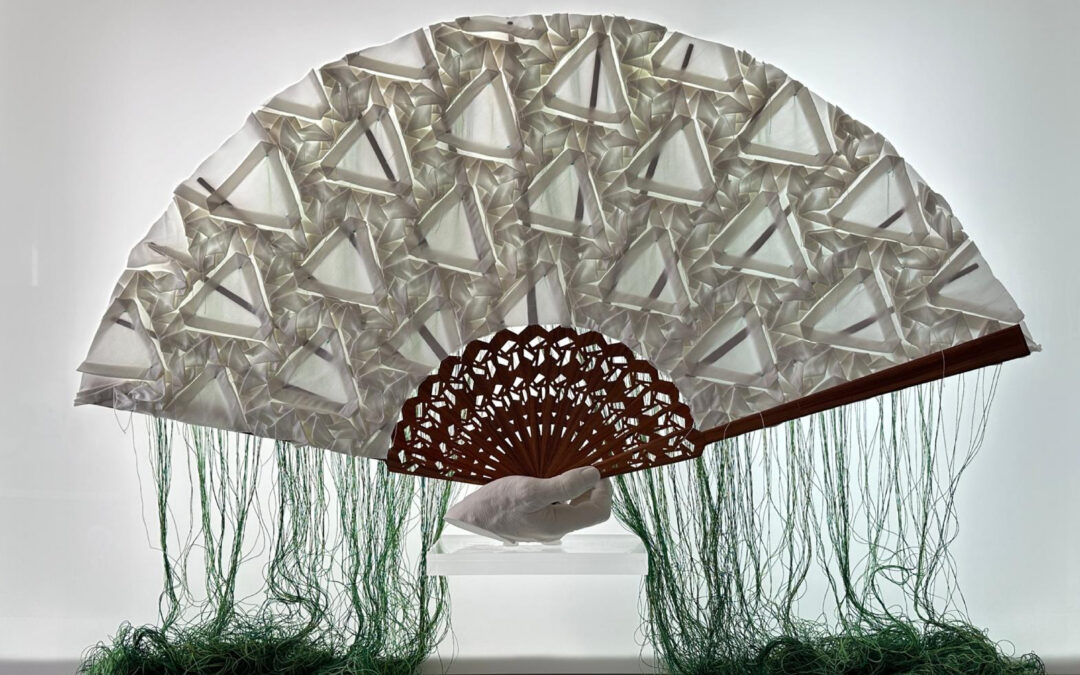

Lastly, but certainly not least, we touch on Jabu’s film The Dream That Refused Me – commissioned by story-telling haven, NOWNESS. Working with dance students from Khayelitsha that Jabu had previously documented, the film was forged from relationships. Centred around a poem written and performed by Siabonga called “Ubizo”, The Dream That Refused Me is a world created to hold the poem in its full manifestation. The film incorporates 3D technology with 3D collage artist Zas Lehulee, the film is a whirlwind expression of the dancers, Jabu’s directorial vision, Unathi Mkonto’s styling and costume design, and original composition by Likhona among other potent creatives. “The film is about having a certain calling, either as a sangoma or in a certain role – and fighting that calling, which leads to certain situations. The breakdown of one’s life when we deny our purpose or destiny – and finding new ways to exist in the modern world with ancient, ancestral practices.” A stunning depiction of Afro-centric and Afro-futurist realities – I am so excited to witness Jabu’s continuing evolution.