To be “thrifty” is to be economical – and with the rise of second-hand resellers, vintage stores and the culture around thrifting – the fashion purchasing landscape has seen popularisation of consumers opting for unique, often cheaper priced garments; a welcomed challenge against the onslaught of fast-fashion’s hyper-consumption and ceaseless trends. In Cape Town, second-hand culture is an expression of a larger African informal economy, and locally it can be seen to emanate from vendors at Grand Parade, outwardly across markets, online, and brick & mortar stores. This landscape of thrifting, although positive in its intention, speaks to a greater systemic issue – where countries in the northern hemisphere send massive bales, regularly, to key ports along the continent’s coasts; most notably, this is an almost epidemic aspect of garment trading in Accra, as researched and reported by the OR Foundation’s project Dead White Man’s Clothing. During my initial “thrifting” awakening as a teenager, there was a store in Spencer Rd, Salt River that brought in bales of army jackets, fur coats etc – redirecting these garments from “aid” towards profit for the owner. While this appears deeply problematic, there is also the inherent problem with “aid” – the idea that the global south should only advance or benefit from the charity of wealthier countries. As with any large-scale systematic reflection of our greater economic state as a society, I urge you to dig deeper into thrifting as a practice for low-income people; and the care we must take in understanding the nuances of gentrification of this practice.

I spoke to a number of store owners around the city on their thoughts about thrifting. Iin asking Abigail Merhar of Eku Collective how curating and re-selling can be more dynamic for her clients than conventional fashion retail, she says “I think it makes the creative process behind curating your wardrobe much more fun and dynamic. It challenges you to find new, fresh ways to wear clothing you wouldn’t otherwise consider wearing. You will be able to find one of a kind treasures, collectors pieces and pieces that no one else around you would be likely to find as well. You also know that the footprint and impact of your purchase is much lower than that of a conventional fast fashion or retail purchase.” Thrifting is an act of lengthening the life-cycle of a garment, preventing it from reaching a final fate in a landfill – where it may never degrade, along with the rest of our intense amounts of waste as a species. Robyn Uria and Michelle Solomon of Kaap Diem – a thrifting collective located in Bo-Kaap – speak to the circulatory of thrifting, and normalising it as a desirable purchasing method for young people, “We really believe that gently owned or previously loved fashion always has a place for a new home. If we can contribute to well priced pre-loved fashion being continuously cycled rather than putting additional strain on the environment we are doing our part in ensuring a healthy future for our beautiful planet. Styles come and go but they are cyclical and there will always be a demand for them again. Our key is to have an ecosystem of trading and buying or selling of beautiful styles but not necessarily designer brands. We try to cater to all genres and sizes.”

A favourite of Cape Tonian thrifters, Sarah Byram’s Better Half Store is an exceptionally curated offering in Observatory; showcasing the possibilities for thrifting as effortlessly aligned to a concept store setting as any brand or label, and not merely the usual chaos of rails and piles of clothing (although the latter is always a fun exercise in finding the right piece).

Sarah explains the origins of Better Half, and how it has always functioned to complement and host local, small-scale designers embodying the same values, “The backbone of Better Half has always been rooted in sustainability, although it is my belief that no brand, no matter how big or small, is 100% sustainable. We can only do our best to be as transparent as possible while still aiming to run a profitable business. Other than sustainability, quality and consistency are our core points of focus, so we consider each of these in every decision that is made. When we opened our store in 2017, our focus was primarily on second hand clothing, specifically 70s – 90s garments. By 2018, we were ready to open up a store in Johannesburg and decided to run a 6 month pop up at 99 Juta Street called Better Half and Friends.The aim was to spotlight upcoming Cape Town brands, and included some of our favourite women-run brands such as Sama Sama, Artclub and Akina.” The store, online and physically, is set to host more events in the future – as Sarah grows the adaptive nature of Better Half’s vision, “In 2019 we broke down a wall and expanded our store to include a curated range of dècor and homeware pieces, sourced locally or from independent family run businesses in India. This expansion seemed like the natural evolution of the brand and had always been a dream of mine. A treasure-trove oasis of carefully curated and exhibited items, my aim for this version of Better Half was to spark joy and inspiration within our customers to explore their unique style through offering an alternative to mass manufactured garments and homeware pieces. The next version of Better Half includes the Better Half Content Studio and A Rentable Section, which we plan to launch this Spring. By 2023, we hope to move fully online, but we’ll keep our store as a base for weekend try-ons and pop up events.”

Shelby Bailey of Threads and Stitches conceptualised her business as a response to the hard-hitting industry scarcity of the COVID pandemic, and utilises the philosophy of “rethink, reuse and recycle” – and has since added an up-cycling brand of her own, using offcuts to create beautifully stitched and unique pieces. Commenting on thrifting as a profession, she speaks to her experience as a thrifting consumer, and the greater responsibility of store-owners to be cognisant on how thrifting needs to remain accessible even as it continues to be more coveted, “For me, it started to change, by rather buying, for the means of necessity, rather than out of want and popularity. I love clothing. Some might say it’s an addiction, and I needed to change how I was doing things and thrifting was my start. There are loads of articles on these issues and how we can convert our wardrobe into something that is fun, recirculating, and sustainable. We as the consumer can also look at personal preferences and style and build a wardrobe that’s durable, functional, and timeless. If we look after our things well enough that the next person can use them then we are creating a sustainable wardrobe. A noticeable difference that I have seen is that thrifting has changed from charity shops circulating in an accessible retail space catering to those that rely on secondhand clothing to becoming infatuated with the new thrift trend and putting up the prices to make necessities unobtainable. This, in turn, causes thrifting businesses to sit with an excess of leftover stock that finds no home.”

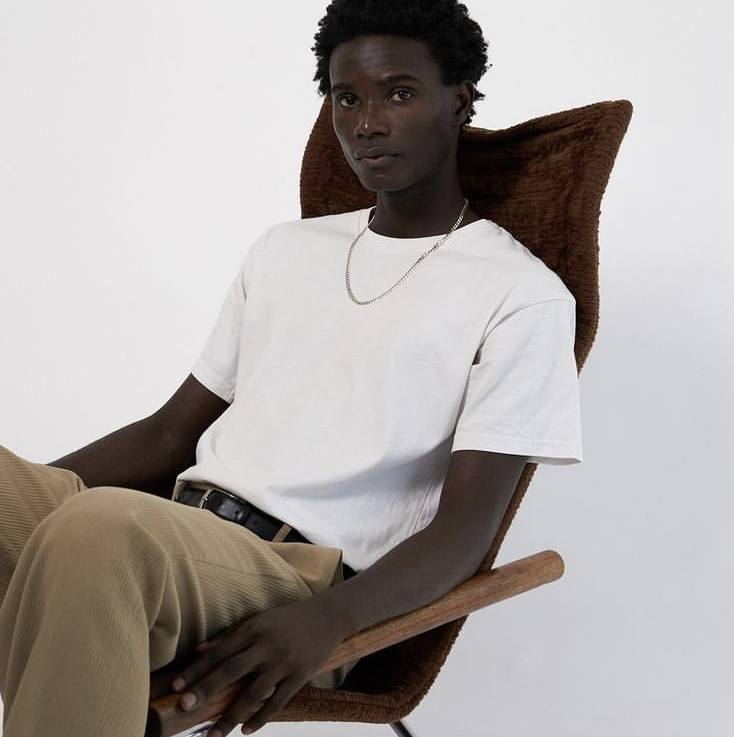

Before Andile Dlamini pioneered BROKE, his initial entry into the thrifting market was through his much loved business Hopeville Grailz; in which he channeled rare finds from his own experience thrifting and styling, to a destination that reflects he and his friends’ affinity and passion for streetwear. Now predominantly curating and reselling pieces that can’t be thrifted in Cape Town like Patta, Palace or Stüssy – Andile comments, “Hopeville is definitely the sister to the clothing Brand BROKE as it inspired us to find our own place in the streets, as we stood out in the colourful and cheap thrifted garments we couldn’t move a thrift store, we had to find a name for us as the movement hence Broke Boys, at that time it was a group of friends just trying to make the most with what they had, everything was achieved through a shoestring budget. The importance of thrifting is that more than anything, it is financial and environmentally sustainable,but besides that it allows you the opportunity to travel back in time through the old clothes that you need to browse through and appreciate the era it came from; trust me they don’t make them like they used to.” The crux of these owner’s vision is young entrepreneurship, each building a business and creative models that speak to their experience as consumers and that of their communities; and this is the essence of thrifting as a practice, born from a joy that cannot be bought at just any store. It is part of a solution, of which we need many, to tackle our growing global fashion-consumption crisis.