I am extremely lucky to have the conversations that I do with a myriad of people; each of whom I hold immense reverence for, in both their varying praxis and for their beingness. Still, each conversation I have seems to unveil an even deeper excitement and revelation about the potentiality of not only South Africa – but life itself. My conversation with Ashleigh Killa and Max Melvill is no exception; in fact, it is one of the most profound to date.

Ash and Max are co-founders of award-winning spatial practice ‘The MAAK’, based in Cape Town. Specifically focused on ‘social impact’ architecture, The MAAK is situated between intersecting realms of design, artistic inquiry – architecture (of course) – and most crucially? People. In a world in which architecture feels a more grand and impersonal execution of human ingenuity than ever; The MAAK’s focus on social impact and public spaces, synonymously, is indisputably human-centric.

This approach, though not explicitly stated by The MAAK, reminds me of the ongoing theory around the ‘Third Space’. This term holds a dual-function; in an urban-planning context, sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the ‘Third Space’ as intrinsically a community space – the first space as being one’s home and the second space as being one’s workplace. So, the Third Space are places that exist beyond the ‘individual’ modes of existence of modern living – and into parks, coffee shops, community centres, libraries and so on. This identification of the Third Space was furthered, more enriching, by critical theorist Homi K. Bhabha; without diving too deeply into his incredible assertions, he describes the possibilities for the Third Space in a decolonial, globalised framework. Bhabha puts forward the notion that the Third Space is a prerequisite for cultural expression today, which in turn facilitates the cherishing, protecting and merging of cultural heritage and diversity.

When we think about architectural practice, or the act of building material containers in which to live – work – play – the civic arena, in our local context, tends to elicit feelings of dullness. Yet, public space, seen through the lens of the theory of Third Space, is one of the most important features of our society. For Max and Ash, their acknowledgement of this arose as early as their studies together; with the two understanding the potential of public buildings to act as ‘north stars’ and beacons of transformation for communities. In a South African context, a richly diverse and complex context, Max explains that “one of the things that makes architecture unique, and the potential of it in our country, is that it’s fundamentally local and fixed. Through this, the potential of craft can be used to connect the identity of a people with the specificity of place. We are definitely driven by this as a studio and it gives us great pride to work with our rich context to create uniquely South African things.”

Workshops and maker-sessions are used to engage with and learn from the eventual users of the space, Otto Foundation.

Interior sketch of the library with reading pit and work area & collage drawing of the entrance to the new library, Otto Foundation.

In asking both Ash and Max the why for public spaces – they each point to the essential social implications of their work. Max notes that, “Although The MAAK is continually evolving as we grow. A golden thread for us, is the idea of ‘publicness’ and inevitably social impact. Because we work predominantly in under-resourced areas, we are critically aware of the potential impact each project can have. Focusing on public buildings (libraries, clinics, creches etc) and public space, has been a way for us to maximise on this potential and focus our craft.” While Ash describes their work as a form of ‘care work’ enacted through architecture; “For me, The MAAK has fundamentally been about people. It hasn’t actually been about buildings. I would have loved to have been in the medicine or care work world in another life, and so public spaces have become this vehicle for me and way of caring for people.”

The MAAK is a process-led practice that strives to move away from ‘outputs’ being the driver of what they do. An important part of this is working in a way that deals with agency as having been experienced by everyone involved. Working in the public realm involves looking at the users of the space as being as important as the client or funder(s) who pays for it. The two note that this opens up each project as a space for serial collaboration and presents the opportunity to engage the act of architecture beyond the conventional modes of typical ‘client/ architect agreements’.

Take their current library project at Rahmaniyeh Primary School in District 6 (being built in collaboration with The Otto Foundation) as an example. Beyond pleasing the school (and the project funders) their primary goal is to engage with and understand the learners themselves. By hosting workshops and making sessions, they have created the container from which they can learn from and build empathy with the eventual users of the space; the learners themselves. This process towards understanding each projects’ needs is not typical in architectural practice – and is what sets The MAAK apart. Max explains “we often talk about ourselves being midwives who are really just trying to safely carry ideas, needs and desires, through the expression of architecture, into reality. In the context of our work it is rarely the client or funder who will make use of the building. Knowing this, it becomes critical for us to find ways of engaging with the people who will actually use the space. It is ultimately their brief (not the clients) that will determine the success of each project.

The MAAK governs an area of ‘sustainability’ or environmentalism which tends to be under emphasised; the need for human beings to exist safely and with dignity. As Ash explains, their thinking is about quality and the experience people will have with the building, “for us, sustainability is as much about the environment as it is about urban resilience. We are lucky to work with a lot of sponsors, some of whom donate materials to our projects. It is our responsibility to make sure that these resources are deployed in a way to lift communities as opposed to becoming a burden on them. Constructing maintenance heavy buildings or using short-term solutions (like containers or prefab structures) do more harm than good- especially in low-income environments.”

Each year, The MAAK hosts ‘Follies in the Veld’ (FITV); a fast-paced ‘design and make’ programme that invites collaborators to experiment with unconventional materials by building a temporary installation together.As Max says, “architecture is typically a very slow process – getting to the point of construction can sometimes take years from the point of conception. Follies in The Veld, in some way, is a reaction to that . It is a chance to act, think, experiment, fail, learn and unlearn quickly. Using chosen materials as the lens to do this, has been a liberating process and has produced wonderous innovations over the years.” For the FITV programme in 2019, The MAAK, in collaboration with visual artist Amy Rusch and the creative collective ‘Our Workshop’, used up-cylced TetraPak to create 2 large canopies in an under-utilised public space in Langa, Cape Town. The profound installation stands testament to how acts of creativity and joy can encourage new life in our cities.

FITV participants working hard mid way through the programme & activation of public space post installation, Courtesy of The MAAK.

Happy face enjoying interacting with the structure, photographed by Sophie Zimmerman.

As a part of the library project they are currently working on in District Six, The MAAK have teamed up with the land activist Zayaan Khan and photographer Kent Andreasen; together they have been interested in exploring deeper stories of land relevant to the area. Max recalls “Guided by Zayaan, we have been sifting through clay reserves that exist in District Six. In this clay we have been discovering bits of building rubble from the houses that would have been demolished there during the forced removals in the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s. We are now in the process of making new bricks from this material that will be used in the construction of the library. For us it is important to find ways, through the architecture, to acknowledge what happened on this land.”

This artistic (for want of a better word) layer of The MAAK’s practice, so laden with emotion and depth, is perhaps the moment I realised that what we were discussing goes far beyond the reach of ‘social impact’. Rather, I would liken Max and Ash’s expression as creative architects to something futuristic – and not in a technological sense – but in a truly sensitive and expansive way. When we are challenged to imagine and create beyond the established means of doing something – then, true ingenuity arises. Speaking to Ash and Max is like peering past the veil of the creative conversations that I have had, and into something entirely new and undiscovered.

Interplay of colours and shadows inside the covered courtyard play area. Photographed by Kent Andreasen.

Kids playing on the adjacent public street to the creche. Photographed by Kent Andreasen.

The new creche is the first piece of formal public infrastructure built in New Rest Valley. Photographed by Kent Andreasen.

For the New Rest Valley Creche in Riebeek Kasteel, Max and Ash convinced their client to not build a wall or fence around the building, instead they maximised the facility’s footprint and used the walls needed in the project to create a secure envelope for the scheme , “We explained that putting buildings behind walls or scary electric fences mitigates the potential for architecture to help build more cohesive, welcoming and dynamic communities.” Max notes. As a child day-care centre, the New Rest Valley Creche demonstrates a thoughtfulness towards the inhabitants of the space; soft, curved walls, provision of shade and opportunities for rest and chilling are perfect for young kids and their parents/caregivers for whom the site now forms part of their everyday lives.

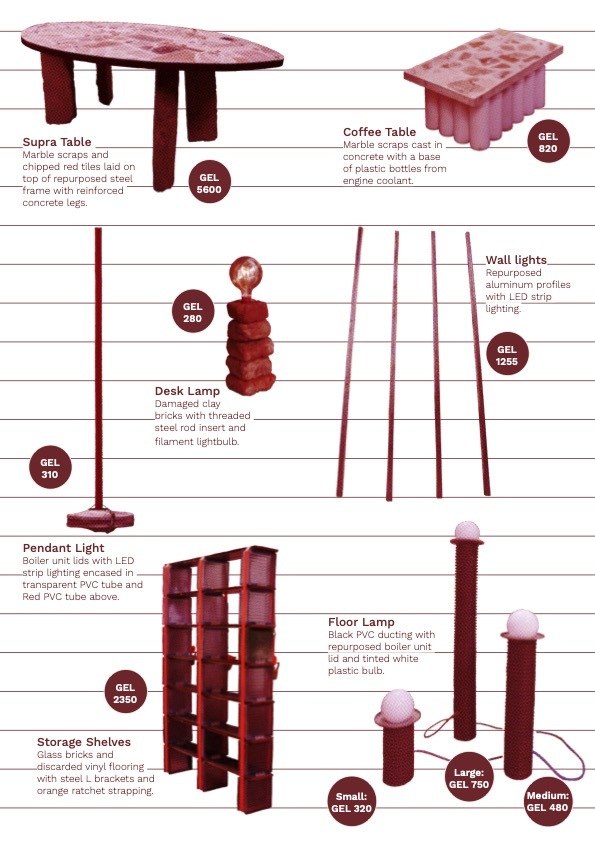

Last year, The MAAK were invited to Georgia by the Tbilisi Architectural Biennial. For this, Ash and Max designed a range of site-specific furniture ‘to raise awareness around the illegal dumping of construction waste in Digomi Meadows, one of the last remaining riparian forests in the region’. Titled ‘Love Thy Monsters’, the project is an iteration of RRRUBBLE – a collaborative research project by The MAAK and Space Saloon, a cross-country collective of researchers, artists and architects. Max says, “we went through this process of foraging the area of Digomi Meadows, which has a very specific and important role in Tbilisi and is at risk of being ruined. From this, we created hyper-contextual furniture pieces that use the material we found to cast light on the tragedy that is occurring in the area. These pieces will be used in the refurbishment of a derelict power station into a new community-space and a listening bar for a local internet radio station.” For Ash and Max, architecture is incontestably also an act of activism; an opportunity for design-thinking to transform our understanding of the world and how we live in it.

Aerial view of the Love Thy Monsters exhibition during setup & public learning about the Dighomi Meadows tragedy at the exhibition opening, photographed by Nino Kakabadze.

Final catalogue of pieces for sale at the Love Thy Monsters exhibition. Courtesy of The MAAK/ Space Saloon.

The MAAK weaves together all the most pertinent threads within a much needed ‘design-as-change’ narrative. Technical ability, precise intentions, thoughtfulness, genuine curiosity and above all – execution, are just some of the inputs that coalesce to form their spatial-lead vision. I bow humbly at their work and what it means for South Africa and the planet’s future.

Written by: Holly Beaton