Xhanti grew up in the Eastern Cape and his initial interest in art stemmed from watching Dragon Ball Z, with his school teacher challenging him to draw subjects other than Goku and Frieza – he shared “It was in grade 6 or 7 where my curiosity began and I realized there’s more to art than just copying things.” He later studied law at his mother’s insistence but eventually pursued art at Michaelis after receiving a scholarship, working primarily in sculpture and printmaking. Being on campus meant he was exposed to diverse perspectives and contexts, where fellow students were fueling their curiosity about differing understandings of the world. This prompted him to create art that poses questions rather than providing answers. For Xhanti, making art was “another form of language, one [he] can’t articulate in any written or spoken form, so [he decided] to create objects to evoke all these questions”.

Today, it is significant to witness contemporary creatives exploring notions of fixed identities, decolonial themes and challenging systemic ideologies in order to find new ways of understanding ourselves and our intersecting contexts. Xhanti has collaborated with many artists working in similar thematic realms. When asked about what informs who he chooses to collaborate with, he says “I don’t have a specific process for choosing collaborators, it happens spontaneously with people whose work or thought process I admire. But, you’ve got to be somewhat interesting, funny, smart and you also have to have tough skin.” While always open to collaboration and having worked collaboratively throughout his artmaking career, Xhanti anticipates his next body of work will focus on expressing more of his individualistic ideas, saying “I don’t think I’m going to collaborate again for a while. There are some creative ideas that I think are quite difficult to have with another person. The next body of work will likely be just my ideas and my thoughts – I’m dedicated to exploring why I have these thoughts. And yeah, I’m just not going to be a little bitch about it.”

Many of Xhanti’s works, although spanning multiple mediums including sculpture, installation, performance, tapestries, print and video are untitled, followed by an identifier. When asked about this naming style, Xhanti’s view is that titles are somewhat unnecessary. “If I thought about it beforehand,” he says, “I would have titled all my works with a number. The work should speak for itself, and naming is more of a concession to people wanting an identifier. Even the term “untitled” feels like a title. Names may be assigned later or just not exist. Not everything has to be compartmentalised, named, boxed, categorised. So it’s not a matter of a protest for naming. It’s just I didn’t think of a name.”

Not only has Xhanti been a practitioner for over two decades, including a 3 month residency in Leipzig, he’s also taught art in academia. About his experiences of teaching, he adds, “It’s nice to be in an academic space, to be thinking with new thinkers. There are some brilliant people out there. My teaching style was to always let people do whatever they want and let them teach each other. It’s been interesting to see how people engage: with each other, with work, with the institute and with me.

I’m also learning from them. I’m giving them enough room to develop their identities and character – not to have to get a green light from me but be able to oppose an idea. I encourage people to speak out loud and voice exactly how they feel and not worry about whether or not they will get a mark at the end of it. It’s not about the grade, it’s about the work.”

One of Xhanti’s earlier works that has stayed with me personally is ‘IsiXhosa 2nd Additional Language (How to Click)’. The video he created captures the essence of his artistic style with precision: it’s quick-witted, hard-hitting, humorous and poignant. Xhanti speaks about this work being created spontaneously – when asked if this is usually how his concepts and ideas come about, or whether they are born out of research and a longer development process, he shares “this work happened spontaneously because of people trying to pronounce my name. My work differs, there are times where I’m consciously reading and trying to find something out. Most of my work comes from conversations, observations, finding something funny or finding dark areas in humor.”

“I feel the more organic works are the ones that are interesting, because I also get bored. Sometimes I see materials or objects and just think about those objects – think about their relation to me. That’s where something interesting can happen.”

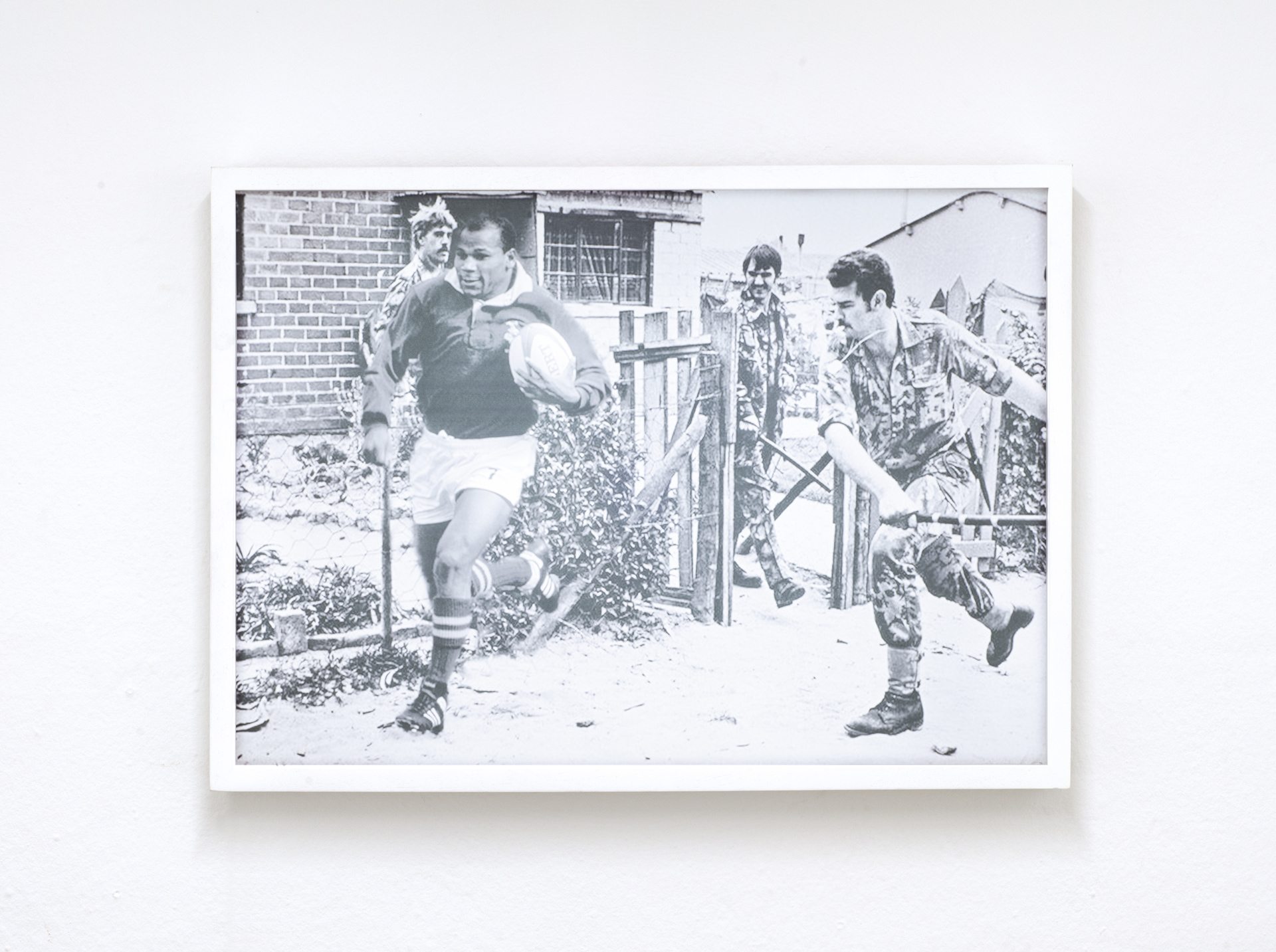

‘Thaba Nchu’ by Xhanti Zwelendaba and Ben Stanwix. Photography courtesy of RESERVOIR

‘Thaba Nchu’ by Xhanti Zwelendaba and Ben Stanwix. Photography courtesy of RESERVOIR

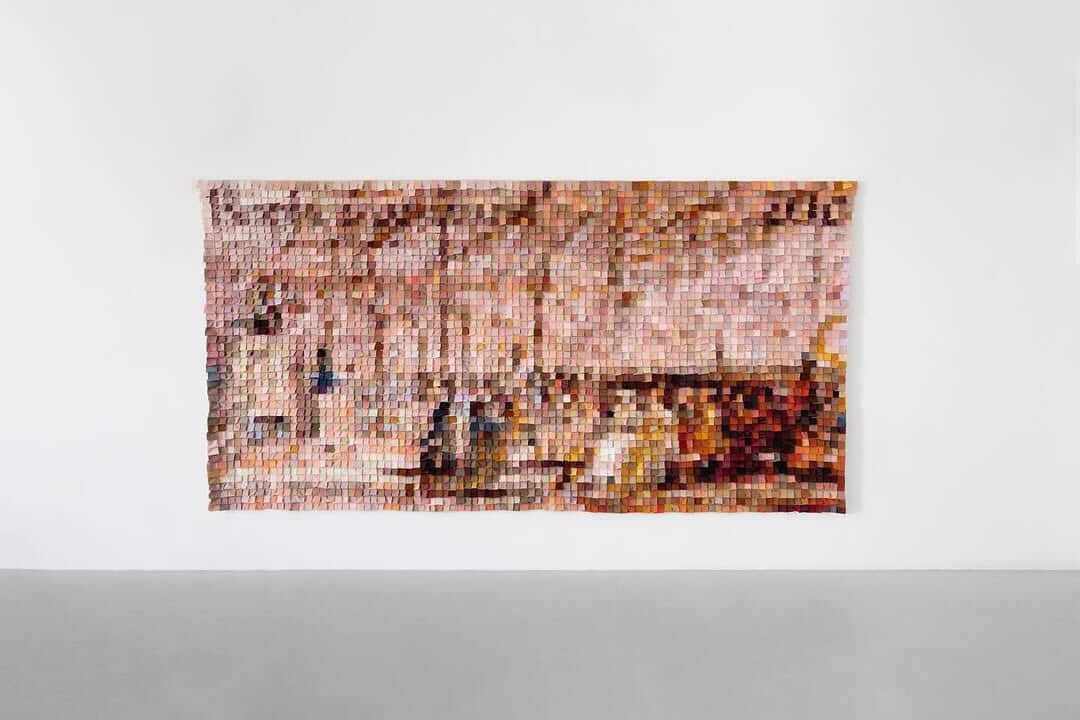

Photography of ‘Animal, Vegetable, Mineral’ courtesy of RESERVOIR

Untitled ‘Amabhokobhoko’ (collaboration with Rowan Smith) and the Stamp series (collaboration with Ben Stanwix) are two examples of how Xhanti use striking contradictions or contrasts superimposed into one visual. In the case of the former, Xhanti’s drawing attention to the relationship between the 1995 World Cup victory (and subsequent nation-building) and the reality of South Africa in a space of transition and tension, being on the brink of civil war. Subjects are taken out of their place to tell an extremely impactful new narrative, or to draw attention to the contradictions that may be difficult to see otherwise. “I’m not trying to manipulate things to a point where I’m trying to change history. I’m just trying to show more sides to a story in one image.”

When asked what he would hope people take away from engaging with his work, in the context of placement in South African society, he says: “My ego isn’t that big. I’m not just thinking that what I’m making is so important. I’m making because I’m curious. So, I hope someone will be as curious as I am or even more curious and then just keep conversations going, keep the dialogue going. I have no aspirations. I just want to create something that starts the conversation. The conversation has to start somewhere.”

‘Animal Vegetable Mineral’ is an upcoming collaborative exhibition with Ben Stanwix at Reservoir. The title is designed to be abstract and akin to the game Twenty Questions, where the objective is to guess what it is. The title reflects the multifaceted nature of the work. The exhibition consists of eleven different components which have been in development since January this year. About the exhibition and how viewers might engage with it, he shares, “I’ve been trying to be very abstract recently. It’s kind of like all these ideas are finally coming into A THING. So it’s just kind of playing on the idea of curiosity – asking ‘what are they trying to say?’ Then you have to actually break it down to a certain point when you get to an answer.” The categories ‘animal, vegetable and mineral’ are a metaphor for trying to understand patterns or ways of getting to grips with something abstract – to see what it could mean to you.

In society, we often talk about being vulnerable, about answering honestly, however, there’s also a real, certain vulnerability in asking questions. The value in this may be to push a little more against your best instinct, letting another person answer how they will and if they will, revealing that there is always more to discover, that there is an infinite amount of unearthed information. Asking questions suggests, like Xhanti does in his quiet confidence, that you are comfortable contending.

‘Animal, Vegetable, Mineral’ exhibition with Ben Stanwix is open at RESERVOIR until 4 July 2025, 7th Floor, Bree Castle House, 68 Bree St, Cape Town City Centre.

Follow Xhanti Zwelendaba on Instagram here

Written by Grace Crooks

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za