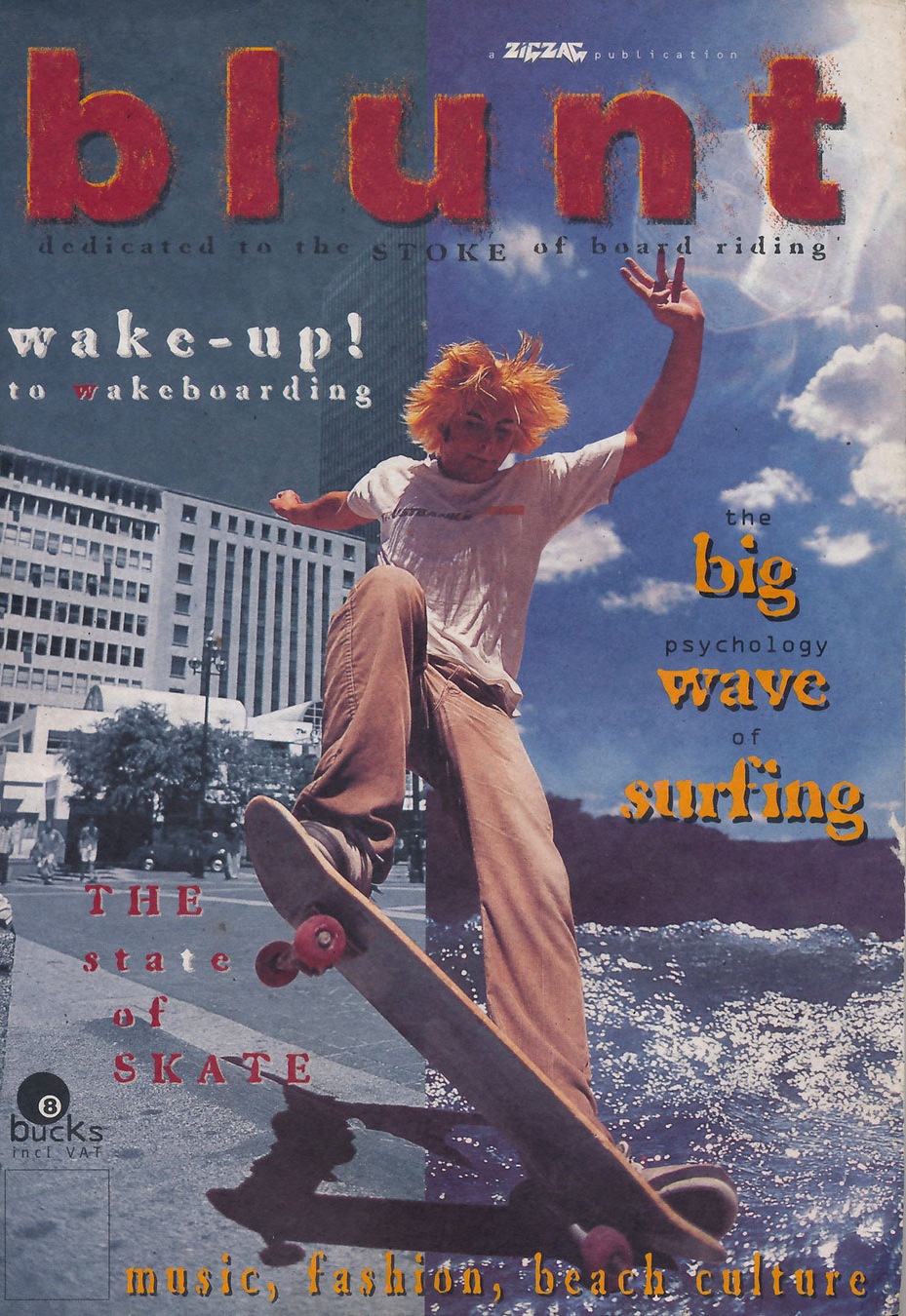

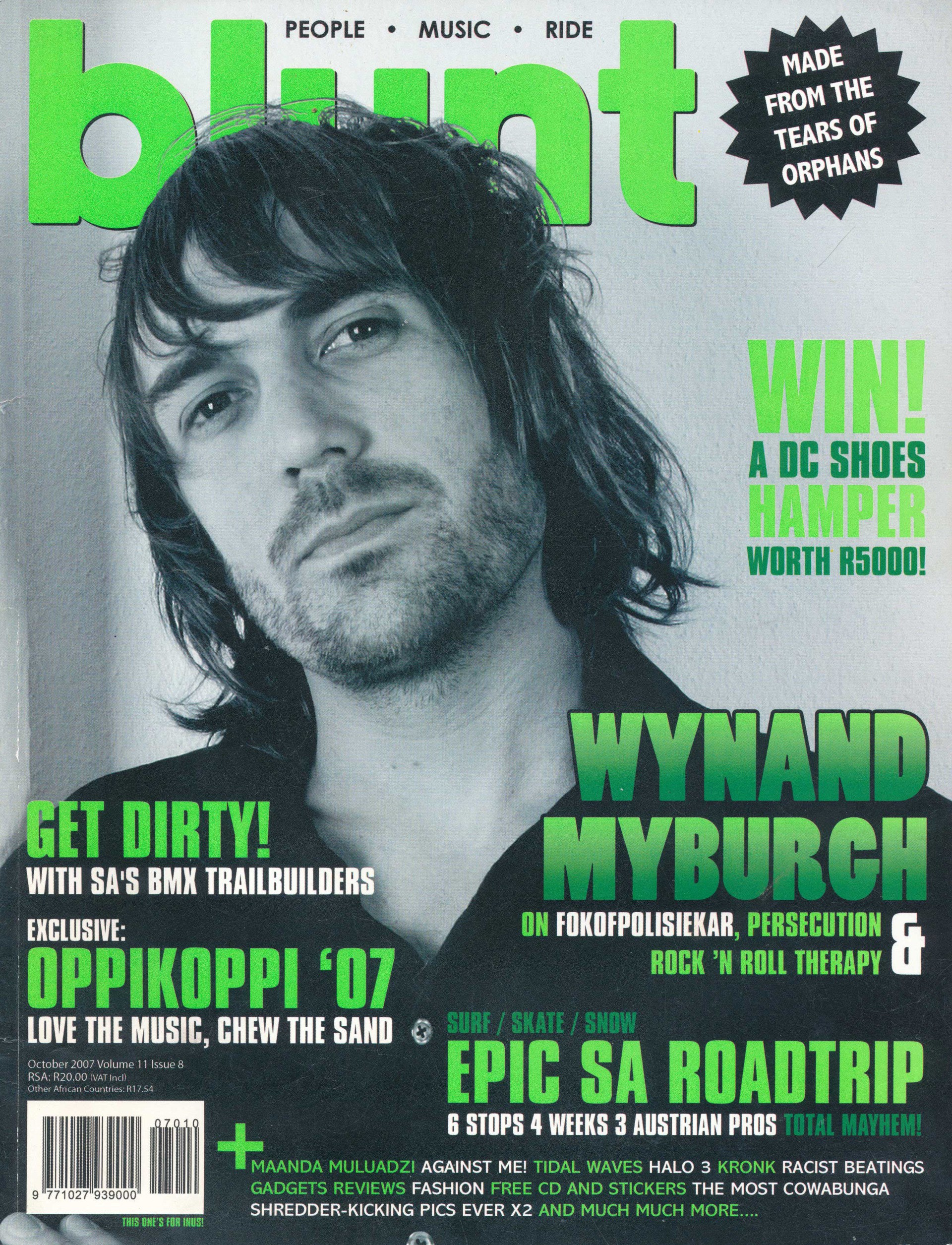

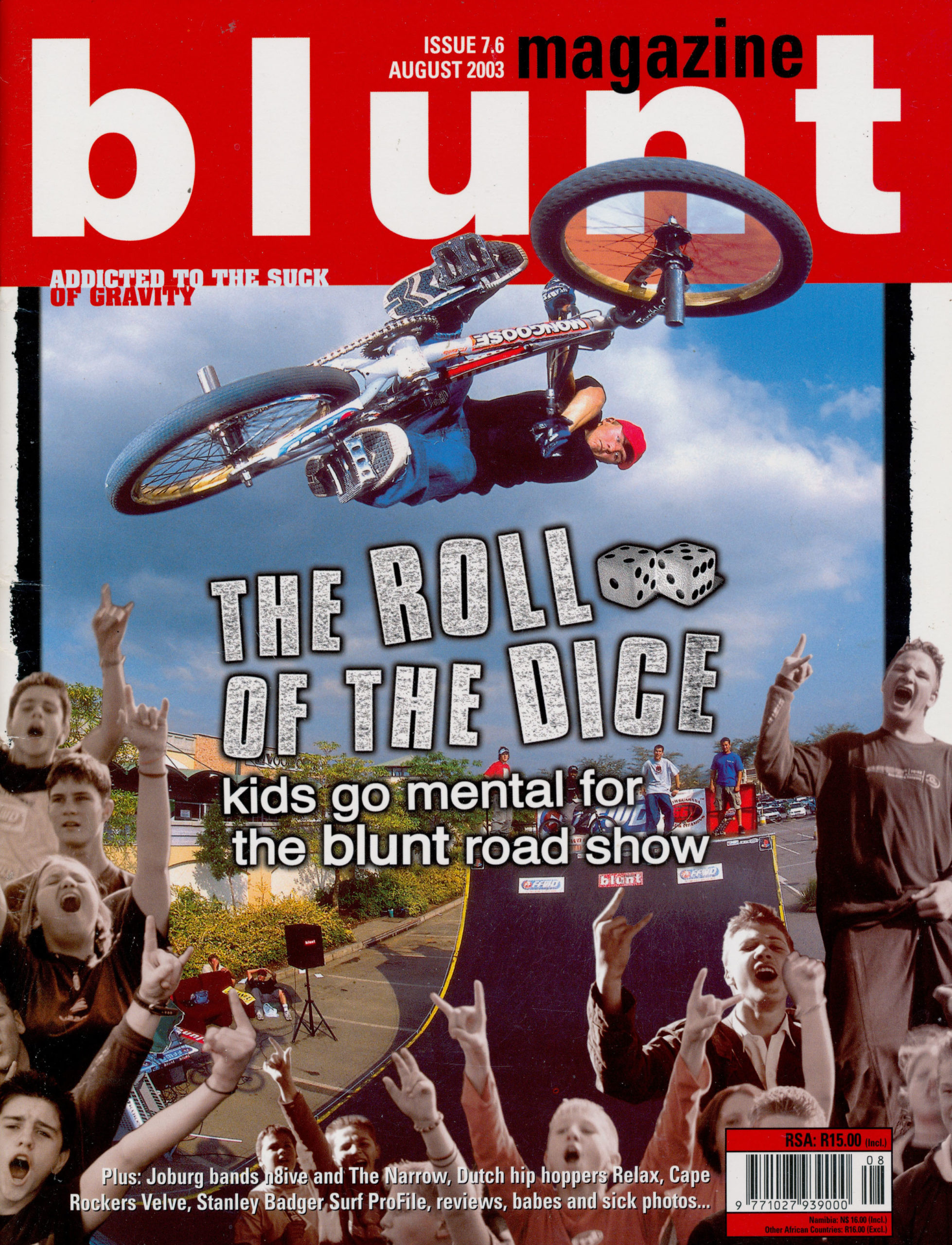

I can’t remember how Blunt Magazine came up on my feed a few weeks ago – but I can tell you that I did a huge double take. Suddenly, I was transported to my childhood – and while I was a kid and tween during the 2000s, Blunt Magazine is a vivid association I have with my older brother Warren, and the older brothers of my best friends – the rebellion and freedom that skateboarding, and all its intersections, has long been as an imprint in our collective consciousness. Scrolling through their feed, as part of their relaunch under founder Miles Masteron, all I can hear is Tom DeLonge’s So-Cal drawl chanting in my head, tempered by memories of Warren donning his trusty gig blazer (emblazoned with pins and badges, some of them being Blunt merch) to head to Wynberg Sports Club. Blunt was the Mecca of South African subculture between 1997 and 2008 – and its closing was one of many sombre tales in the slowly dissolving arena of South African print publishing. Unfortunately, within the constraints of capitalist society, passion and devotion don’t always turn a profit – and in the late 2000s, digital information ramped up to bring us to where we are now; the point of no return. Fourteen years after Blunt’s exit stage left, Miles Masterson has returned to Cape Town after years of toiling corporate fields, and somewhat encouraged by his son’s own growing interest in skating, Miles is determined to bring Blunt back – a necessary task in the 25th year since it was founded, and for a poignant moment in which skateboarding enters a new cycle of importance in Africa.

Honestly, I could talk to Miles for hours – in our conversation, he is a wellspring of wisdom and a guardian of a particularly special time in South Africa. Post-1994, our country began to open up to the world – and suddenly, we were able to engage directly with the global occurrences in adrenaline sports, music, clothing and the acceleration of design and art, both digitally and on the streets. Yet, there is a decidedly South African way in which this zeitgeist was being met here – and skating had always been the craft of the misfits. Miles remincises on the earliest conception of Blunt, “I was living in the UK during winter and traveling to surf in the summer. After a long trip to Sumbawa, this beautifully remote island in Indonesia, I came back and felt like I needed a change of some kind. It was the mid-90s, and the internet had made a huge impression on me – especially being in the UK, it was already established – people had websites, email addresses. It was fully happening. It was at this point, late ‘96, where I was on my way to book a surf trip to the Canary Islands, which I had saved up for working 12 hours a day, 7 days a week on building sites and living in a pretty infamous semi-squat house in Lily Road, Hammersmith. On my way there, I saw an advert for a Canon camera – and the next thing I knew, I had bought the camera and was booking a ticket home at SAA. That was the camera I used throughout the early days of Blunt. That was the beginning of it – that decision to come home. I kind of knew things were going to take off here in the scene – a skate and surf scene that had a renewed sense of autonomy, freedom and a democratic vision.”

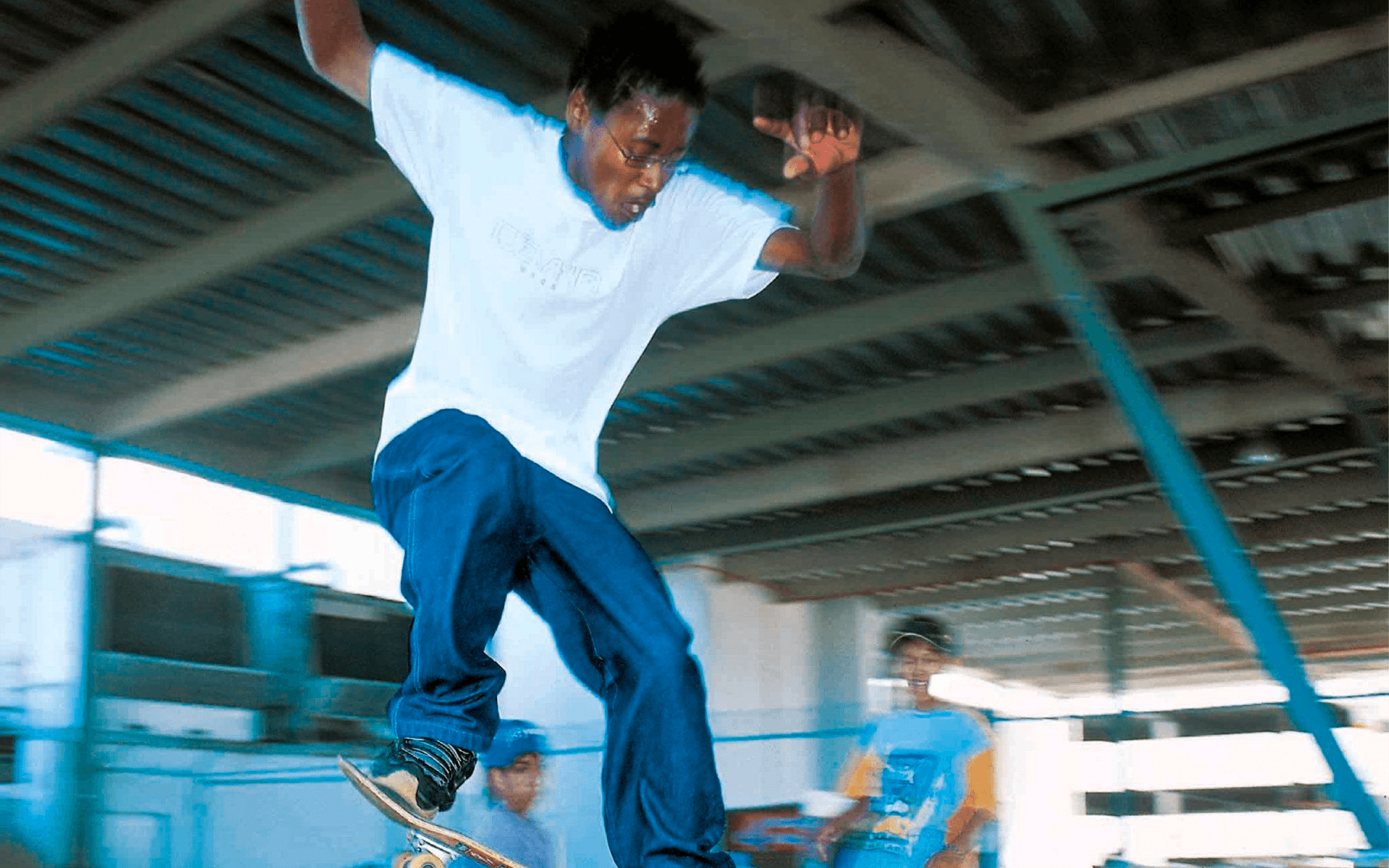

When the first issue of Blunt was born, July 1997, it had been precipitated by Mile’s working with legendary surf photographer Lance Slabbert – who himself was stepping into shooting fashion. It was this multi-thematic interest that would foreshadow the vision of Blunt. Skating, in many ways, is a conduit for punk, hip-hop, graffiti, streetwear – gigs, dive bars, the beach, festivals – it’s the physical arm of a much larger entity largely defined by an innate resilience among young people against all manner of the manipulation (subtle and overt) of human beings by a rigid, oppressive society. This was Miles’ “aha!” moment – he wanted to make a magazine that captured all of it; the sounds, the movement, the energy of this attitude; for himself and his own lived experience growing up skating in Hout Bay, and for those around him too – but particularly so, for the kids who he knew would need the respite skating and its community can offer. In reflecting on the self-expression of subcultural spaces, a clear indicator of Blunt Magazine’s presence in South Africa, and stickers were one such way Miles knew they were on course, “In our first year of launching, we had R2000 available for marketing. That’s it. I spent the entire budget on stickers – and this became a synonymous part of our magazine. Our first year was quite slow, we sold about 4000 copies, and then the second year it blew up to 10000 – and then we became one of the fastest growing magazines in the country, and by the fifth year we were in the top fifty magazines in the country. All the while, I could kind of track this through our stickers – if they were on boards and lamp-posts city to city – but the craziest part was when we went on roadtrips, arrive in small dorpies and find Blunt stickers emblazoned like a coded message, a reminder that the thread we were putting out was really running through the country.” Miles expresses a deeply emotive recall of this – telling me that the magazine was exactly for those kids without access, of all races and backgrounds. In Cape Town, Durban and Joburg the culture and scene was alive and well with events, gigs and comps growing steadily, where people could gather and connect – but further out, in the many parts of our country home to small towns, skating was still a reprieve from that isolation that often is often the drawcard for those who find the sport.

“I don’t think we would have been Blunt, the way we were, without the music component. We gave a tangible bridge between skating and the sounds that inform this passion. By the third year, half the magazine was dedicated to music – and it’s always been the glue that has held these subcultures together. Alongside this the tattooists, the spray-can artists and those dabbling in graphic design found a home I think – you know, I don’t know anyone really who skates that isn’t intrinsically creative. I think the outlawed nature of skating draws in naturally rebellious people – because skating is difficult, too. It takes a lot of practice, discipline and you sign up to get hurt and be in serious physical pain at certain points. We could reach the kids who weren’t jocks, who listened to alternative music and wore strange clothes, and I think Blunt showed them that hey, this spirit is forever – you can grow up, and still be different, and that’s a beautiful thing. Skating, music and creativity is our escape and remedy.” Miles muses about the intention and impact Blunt grew to have, and the voice he felt Blunt was able to give South African kids in those years. I ask Miles why now, for Blunt’s return? “We used to get letters about the way Blunt made kids feel back then, and I feel that there is a need for that now. Especially as we are seeing skating opening up to girls and women, and more so across racial lines too – and I think magazines, whether digital or print, are powerful for telling these stories, by the people for the people. I still skate, even today at 50 years old, and I think both the industry needs it, but we need it too. I am sort of an elder now, and I want to pass down what Blunt was and still is – especially now that I am watching my son get into skating, and be so curious about this thing we started before he was even born.”

Since the Dogtown era of the 70s (Emile Hirsch as Jay Adams in Lords of Dogtown was my first crush, aside from Kurt Cobain) and the invention of the polyurethane wheel – skateboarding remains a pulsing refuge. From the rise of skateboarding among girls in Bangladesh to the work of Skateistan from Afghanistan to Cambodia, and even here in South Africa – what was once a wayward activity for outcasts is now a powerful tool for education and support throughout the world. Virgil’s legacy lives on in Ghana through the opening of the Off-White skate park, and we have many initiatives in South Africa such as the skate park at Thanda’s Community Centre in Mtwalume, KZN. It’s with this dedication to the next generation of skateboarders and creatives across the world that Miles, and us at CEC, believe wholeheartedly in Blunt’s comeback. Viva.

Written by: Holly Bell Beaton