We know her so well. She’s gorgeous, she’s wealthy, she’s smart, she drives boys crazy, and above all, she’s the absolute worst. She’s the Popular Mean Girl in every teen movie we grew up watching, and she’s completely made up. Despite her not existing, this archetype has stuck around for decades, still being used today in movies, series and reality TV; so implanted in our minds that we’re convinced that her real-life incarnation must be out there somewhere, waiting to pounce and make us feel bad. Despite feminism, pop culture and representation making so many progressive strides, why is the ‘Popular Mean Girl’ so indelible and why the hell was she created in the first place?

What is it that makes this character so quintessentially her? She’s stereotypically beautiful of course, but she’s also really f*cking mean. From one of her first iterations, embodied by Heather Chandler in Heathers to Chanel No.1 in Scream Queens; she’s tall, skinny, white, and she has salon-quality hair styling every day despite being in high school. She’s also always rich – and not in a ‘quiet luxury’ kind of way. We’ll see ostentatious shots of her family’s massive suburban house, her fancy car – often convertible sports cars (it was the 90s), her huge bedroom and bed, and most obviously, her incredible wardrobe.

Not only does this character have the most enviable clothes, she also has the style and glamour to match. Sarah Michelle Gellar’s Kathryn in Cruel Intentions was more chic as a high schooler than most 30-somethings (please note, she also wore a rosary that was stashed with cocaine – in what world?!) as were the likes of Blair Waldorf and Regina George who followed in her footsteps.

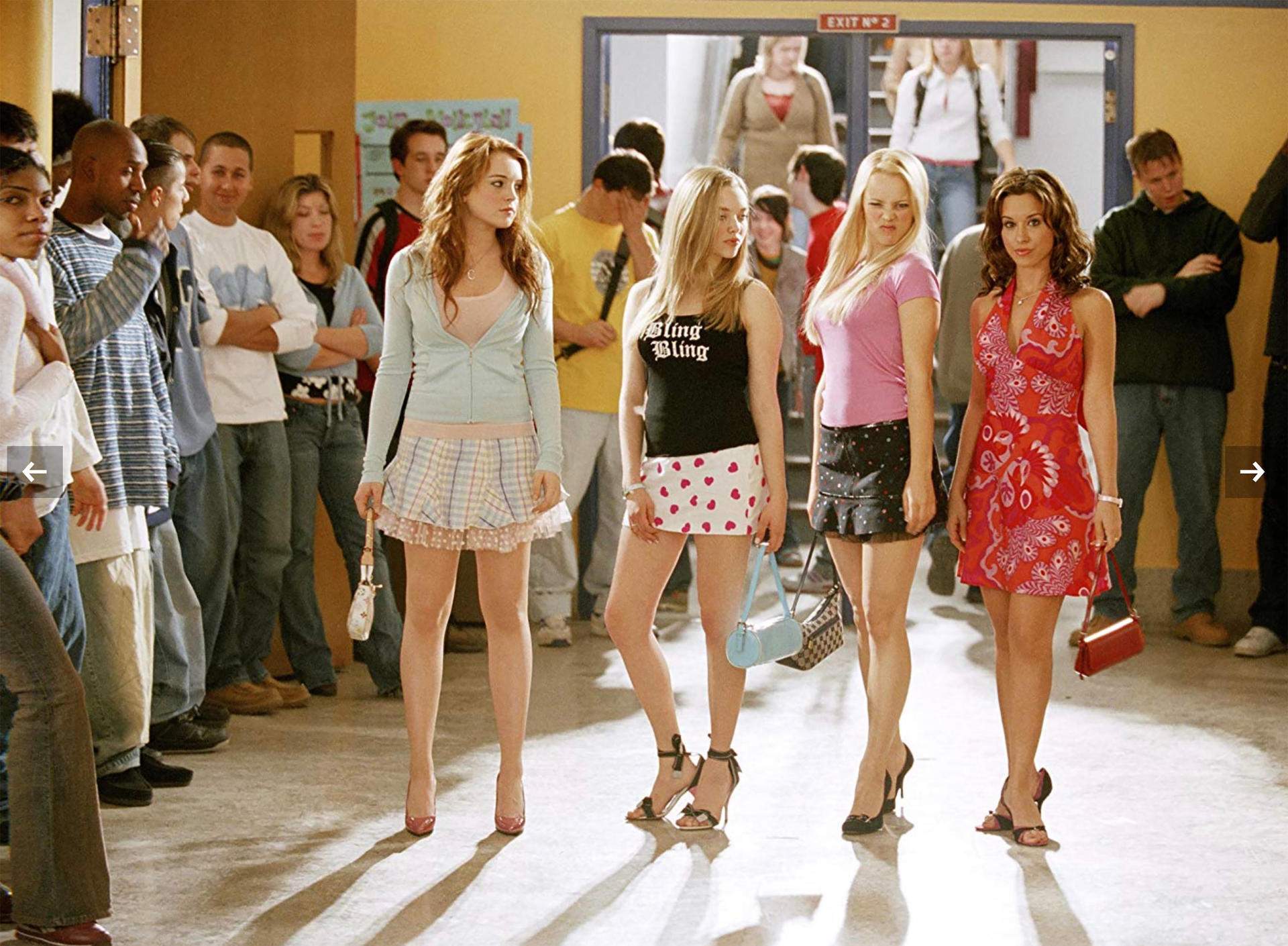

She’s got a couple of minions who are undyingly loyal – if they aren’t, the consequences are brutal. The purpose of these helpless women with zero self-determination is always to show how powerful or exceptional our Popular Mean Girl is. For some reason, this is also demonstrated through the power walk. Strutting down the school corridor in formation is canon – remember Rose McGowan cat walking down the hallway in Jaw Breaker? This had girls all over the world trying to master the slow motion walk.

(Jawbreaker 1999)

She’s proudly sexually experienced – the highest form of street cred according to American high school movies. The Popular Mean Girl is extremely and openly sexual towards men but never labelled a slut. However, should any other girl reveal their sexual exploits, they are labelled a slut by her. Get it? Lastly – she is violent. In every type of way. This ranges from your regular mean girl stuff like reading you for filth in front of your whole high school, to mid-range evil activities like spreading rumours about you, to physical violence like shoving you out of her way, and hilariously often, it includes literal murder. From Jawbreaker’s Courtney Shayne to Riverdale’s Cheryl Blossom, it’s shocking how often this girl does crime without blinking an eye.

As much as you root for her downfall at the end of the movie, you also can’t stop watching her. For every scene that makes you understand how selfish and misguided she is, there’s one that makes you covet her hair, or skirt, or boyfriend.

Somewhere along the way, she wasn’t just a movie character anymore. From quoting her sassiest lines to each other at school breaks to gossiping about which popular girl is our very own version of her, to knowingly or unknowingly adopting some of her characteristics to be summoned from within if or when the social situation calls for it – she became a part of our lives and our understanding of womanhood. Even though we know logically that these characters are exaggerated and unrealistic and we ourselves can’t be anything like her, we can’t shake the memory that at some point, she was who and what we wanted to be. And if we didn’t want that for ourselves, we knew someone who did.

To get into the discourse of it all, the Popular Mean Girl trope is a caricature fuelling internalised misogyny in all of us. Ironically, she’s often written by men. As much as we know that she is an exaggerated and unrealistic movie character, she is so ingrained in our minds that it feels like surely some of her must be real – and must be present in real women. Hollywood has pulled this long-con on us over decades, in an act of what we would now call next-level gaslighting. This archetype made us feel bad for not being unrealistically beautiful, rich or thin but more than that, did it encourage an era of bullying that caused more damage than anyone could have expected? These movies told us that being mean is what made you popular – we can’t help but wonder what this did for the psyche of teenagers growing up?

Alamy Licensed Image, Mean Girls 2004, Paramount Pictures film

The ‘mean girl’ character was also almost exclusively played by white women. This is unsurprising, as it’s only in recent years that Hollywood has started to address inclusive and accurate representation. Presenting the The Mean Girl Archetype as exclusively white was particularly harmful in perpetuating distorted and inaccurate beauty standards; it insinuated that to be white and to be horrible – was to be cool or to be worthy. Writing that out feels so insane – the mental gymnastics we had to do to even make that make sense!

For young girls of colour, this portrayal can reinforce incredibly harmful ideals of beauty and race; particularly in the formative years of self-esteem building, such as girlhood and teenhood. It sounds weird to say we deserved more brown Mean Girls in movies – but yes, villains need diversification too.

A lack of representation, especially in a character that felt so vital when we were growing up, is deeply alienating. If there was a pecking order (imaginary or real), it meant that you were at the bottom automatically. For brown girls who went to predominantly white schools, real life and movies could become dangerously conflated.

In 2002, Rosaline Wiseman published her book “Queen Bees and Wannabes”. This book was written for the parents of teenage girls and specifically focuses on the ways in which highschool girls formed cliques and advised parents on how to handle patterns of aggressive behaviour. Though it is hard to measure exactly how influential these characters have been – speak to anyone who may have been a high school girl at one point and they’ll describe a similar experience: of seeking unattainable beauty standards, the fear of gossip and rumours, the fear of social exclusion or ostracization – and finally, competition between girls in the pursuit of the male gaze. Whether these were purported by real people in their school experience or resultant anxiety from pop culture, to say that the mean girl trope was almost a cultural phenomenon is truly an understatement.

Wiseman’s book is a New York Times bestseller and has since been updated, now on its third edition. The book was also used by Tina Fey as the premise for the 2014 movie, Mean Girls; the movie that we all know and love (and now recently re-released), which was the first time a high school teen flick felt remotely relatable by offering a point of view by the ‘underdogs’. It was the first of its kind that called out and exposed the characters’ tactics through showing a less than glamorous fall from grace, casting the trope – most embodied by Regina George – as a caricature rather than someone to be envied. This brought some kind of redemptive justice for anyone and everyone who has been targeted by the ‘mean girls’ in real life, shattering the grip that this character had on girlhood during the 2000s.

Since then, we’ve seen more Popular Mean Girls that we can sympathise with, and even root for. In Jennifer’s Body, Jennifer starts out as the typical hot cheerleader who acts as a bully to her Nice Girl best friend Needy. But with its body horror plot, her character is a lesson in how toxic masculinity and male aggression doesn’t discriminate.

Alamy Licensed Image, Cruel Intentions 1999

On TV, mean girls like Glee’s Santana and Euphoria’s Maddy not only represented girls of other races, but also came with back stories and contexts that we could understand if not empathise with.

Most recently, movies playing in the teen drama genre are blurring the binary of tropes completely. In a hilarious and heartwarming twist, Bottoms makes the good girls the assholes and the hot girls the sweethearts.

The ‘Popular Mean Girl’ is finally getting the much-needed makeover she’s needed, and her future is looking bright. Do you love her, or do you hate her?

Editor’s Note: Coincidentally whilst editing this piece, I discovered The New York Times’ ‘Critics at Large’ podcast titled “Why we can’t quit the mean girl” – for a deep delve and brilliantly articulated conversation on the discourse of the mean girl trope, I highly recommend giving this a listen.

Written by: Devaksha Vallabhjee