It can be hard to remember that the cloth and thread that drape our bodies are the result of nature’s most remarkable work (the lifecycle of cotton is from the soil to our skin) or science’s feats (petroleum becoming nylon on clothing racks) and these ingenuities have fostered fashion and design in ways that could never have been imagined, even a hundred years ago. Instead of catapulting us further in advancements; we stand to lose everything we have evolved to become, and all we have built. Not least because fashion has a massive waste problem.

Annually, the industry generates around 92 million tonnes of textile waste, with landfills around the world brimming in materials that will take hundreds of years to decompose; and materials like nylon which are petroleum based are unlikely to ever actually break down. Most often, textile waste is set alight and burned, emitting hazardous greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Surplus textiles and garments are built into the fashion system with supply chains designed to generate obscene quantities to stay ahead of the trend cycle and strenuous competition. These issues are difficult to comprehend and hard to digest against the backdrop of climate change’s prevailing presence in day to day life – but, I’m here to assure you that we seem to finally be at the precipice of urgent change.

DTS, Sustainability, Mackenzie Freemire.

Sustainable problem-solving and design-led thinking has disrupted the industry for some years now with brands, academics and experts seeding innumerable ways in which the issue of over-production and waste can be addressed. The problem is that it’s not really incentivised for large companies to change, nor are corporate conglomerates generally famed for their ability to restructure based on conscience. In a politically divisive world, news of actual policy changes that address supply chain hindrances to sustainability are rare. Just recently, governments of the European Union have proposed a ban on the destruction of unsold textiles with immediate effect, as Reuters reports “The EU governments have agreed that a destruction ban on unsold clothing should apply immediately, rather than waiting for the EU executive to carry out an assessment that could have lasted three years. Medium-sized companies, with fewer than 250 workers, would have a transition period of four years, while the smallest companies, with fewer than 50, would be exempt.”

In addition, the new law would initiate a requirement for ‘digital product passport’ issued with purchases which would detail the sustainability (or lack thereof) so that consumers are prompted to make informed decisions. The potential of laws like this could have stunning systemic effects and come as a promise of a new dawn should more countries around the world follow suit. The fashion industry’s global supply chains are complex and often lack transparency, making it challenging to trace the origins of materials and track the environmental and social impacts associated with production. Ensuring transparency throughout the supply chain, from sourcing raw materials to manufacturing and distribution, is essential for identifying and mitigating sustainability issues such as unethical labour practices, excessive resource consumption, and pollution – so this historic ban by the EU could be one of the first we see to enact true and regenerative change within fashion.

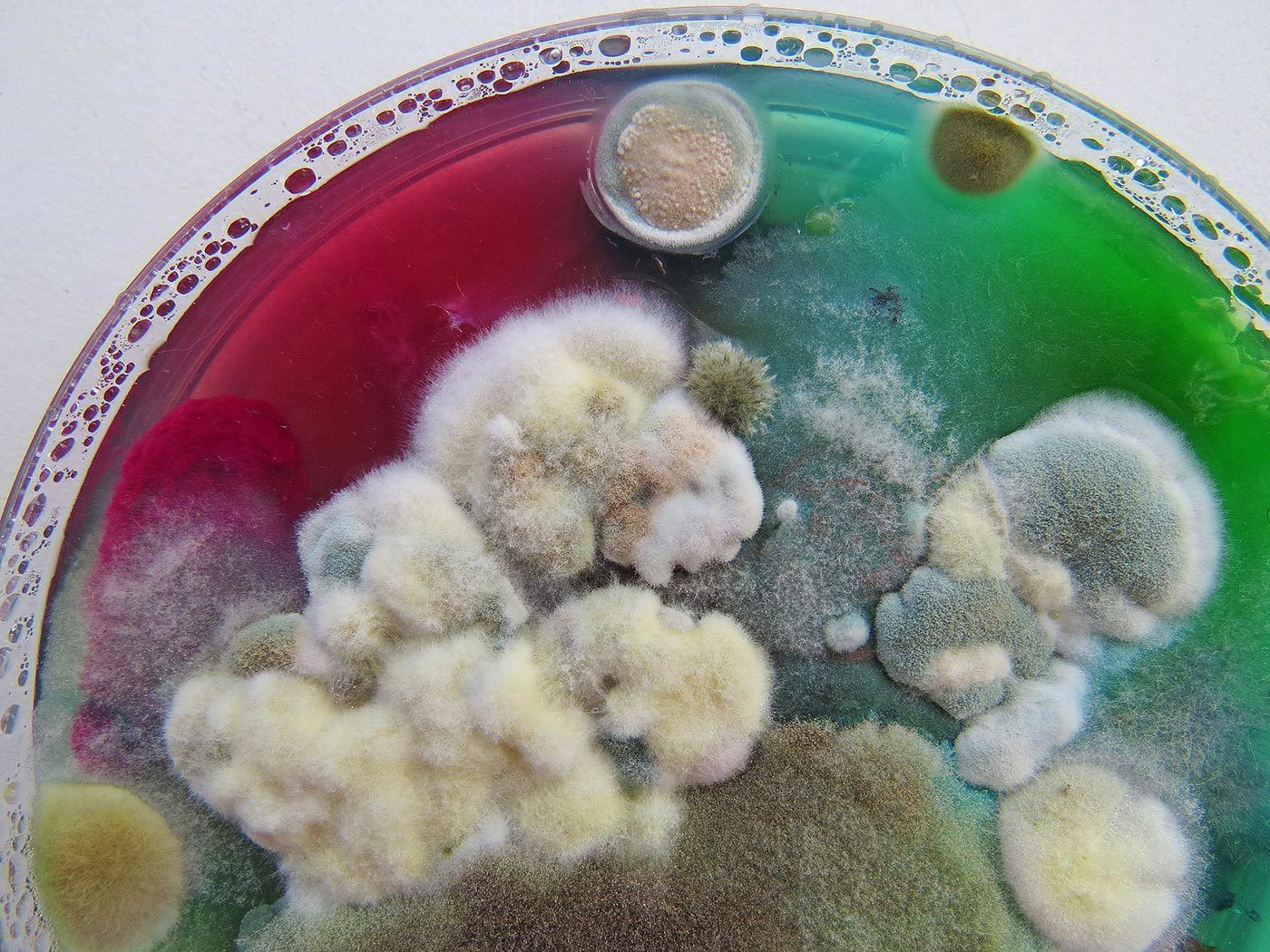

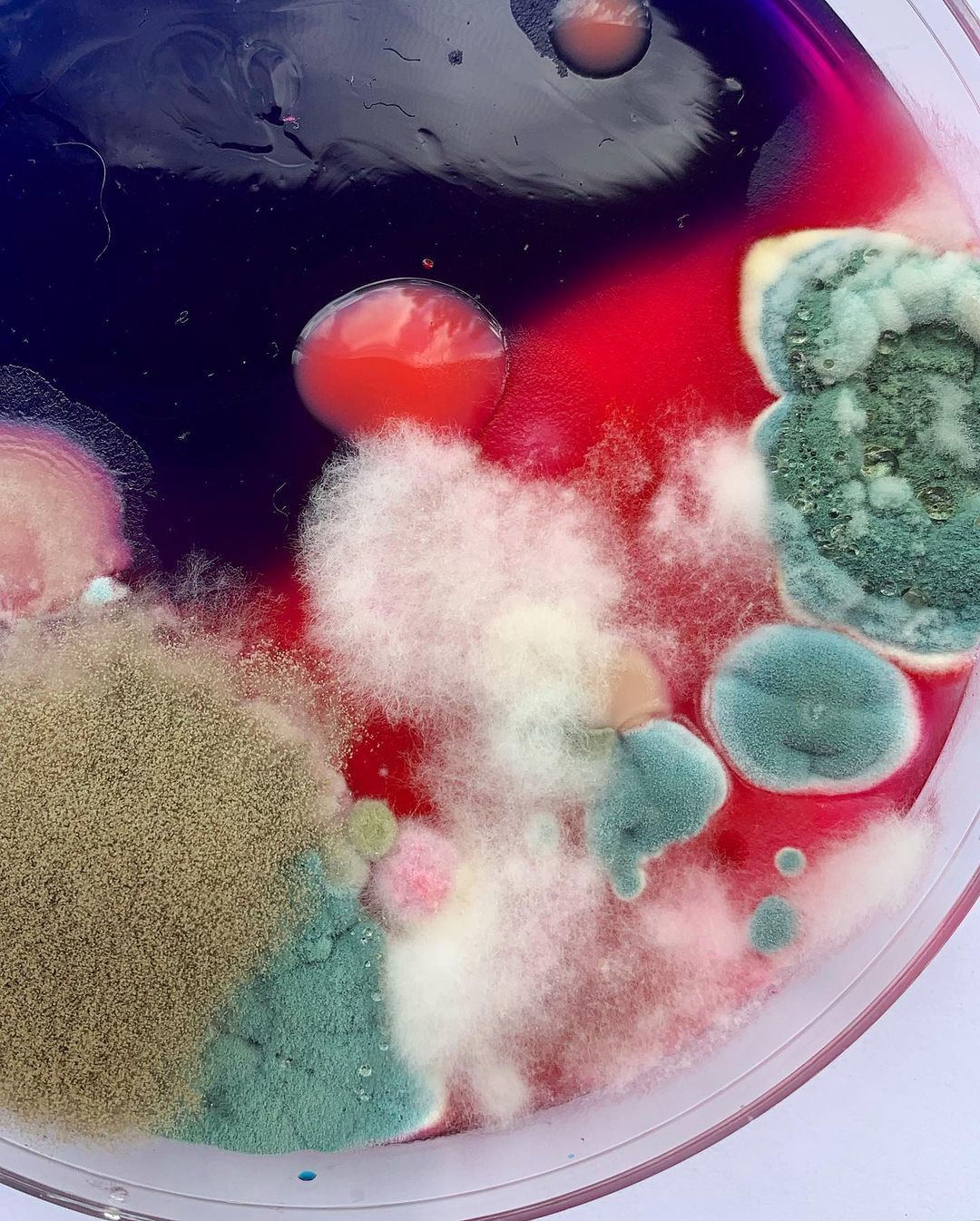

The convergence between design and science continues to prosper with the field of biotechnology asserting itself as a space that could potentially reshape our sartorial futures. In a recent episode of WGSN’s podcast ‘Create Tomorrow’ was in conversation with Jen Keane of biotechnology company, Modern Synthesis, and she was quoted as saying something so poetic about biomaterials, “I am weaving the warp, while the bacteria grows the weft’, pointing to this delightfully symbiotic relationship within biomaterials between human and microbe. Together, the warp and weft threads form the interlaced structure of a woven fabric. The warp provides the fabric’s lengthwise strength and stability, while the weft contributes to its widthwise characteristics and visual design. Can we imagine a world in which each of us can become reconnected to the dynamic relationship intended for us and nature? Jen describes the inception of their ‘nanocellulose’ fabric for Dezeen, saying “we take waste feedstocks, so sugars from a variety of sources – this could be fruit waste or other agricultural waste – and the bacteria grow on that sugar and naturally produce nanocellulose. They’re really strong fibres and they’re so small that when they stick to themselves, because of their structure, they create these strong bonds. So, you get a really strong, lightweight material.”

DTS, Sustainability, Mackenzie Freemire.

Jen’s company and ones like hers focus on the development of biologically-based fibres derived from renewable resources such as plants, algae, or bacteria, and these fibres can replace traditional synthetic fibres, reducing reliance on petroleum-based materials and lowering environmental impact. A fibre like cotton, while naturally occurring, requires intensive resources including water, land, soil and the uncertainty of seasonal climates. Our microbial wunderkinds signal a return to nature’s ingenuity as a compass for our own problem solving. When one thinks that mycelium, the root structure of fungi, has been used to create a sustainable alternative to animal leather – in controlled environments using agricultural waste as a substrate – it becomes easier to imagine that the visions of our technology-led and nature-infused utopic dreams could come to pass. Biomaterials inherently require circular-thinking, in which the lifecycle of materials and productions are non-linear and can either biodegrade or have multiple life cycles through efficient recycling and upcycling systems.

While biomaterials have been researched in a speculative way as proposed solutions, the issue of scalability and efficiency remains to be seen. Scaling biomaterials often involves investing in research, development, and infrastructure to optimise production processes. Initially, biomaterials can be more expensive compared to conventional materials due to factors like limited availability, specialised production techniques, or higher production costs. In addition, biomaterials may require a different supply chain and infrastructure compared to traditional materials. Establishing reliable and sustainable sources of biomaterial feedstocks, such as plant-based fibres or microbial cultures, can be complex and may face challenges related to sourcing, processing, and transportation.

Microscopic Art by Daria Fedorova @dashaplesen

With a ban on textile destruction by the EU, I predict the increasing presence of upcycling in the fashion industry. Textiles will have to be diverted and we can expect spaces like recent LVMH winner Julie Pelipas’ ‘Bettter’ as a vision of the future, or South Africa’s Alexa Schempers and her brand Rethread. On the surface, ‘Bettter’ reads like every slouchy-minimalist fashion girls dreams; a subversion of men’s suits are the brand’s signature, with Julie one of Eastern Europe’s fashion darlings – the suits are deadstock fabrics, and Pelipas intends to harness the brand as an ‘scaleable upcycling system’ to integrate the practice of reworking deadstock garments into the garment construction process. In my conversation with Alexa Schempers, her strategy for solving fashion’s waste problem consists of three categories, which she described, “I think because we have three different categories – upcycling, ready-to-wear and vintage – it’s kind of like running three, micro-systems under one business. As a small business, figuring one thing out is difficult enough, so the variety is quite challenging. Zooming into each process offers its whole host of challenges, but I think upcycling is perhaps the most unique frontier to face in terms of production. We use vintage garments, taking them apart and re-designing them, and being able to offer this as a product hinges entirely on the availability of supply. There are not many people willing to work in that method because it’s non-traditional, and you’re required to almost think backwards. Then, being able to scale upcycled concepts and designs so that we can offer varying sizes, and not just make once off pieces.” This kind of market-analysis and understanding that educating consumers is vital renders Alexa as a leader in instituting upcycling as a normalised (and chic) practice.

Collective change is a difficult road to embark on when our individualism is fostered under the current political and economic systems that we inhabit. There is brilliance and foresight occurring, and I do believe that the telling signs of climate change (heatwaves, wildfires and so on) are going to prompt even more drastic action by governments around the world. Whether it’s too late, as I sometimes nihilistically assume, is really not the point – our human drive to problem solve and to design will hopefully avail. Fashion has to look at its waste problem with even more microscopic concern than bacteria growing in petri dishes; collaboration with other industries, policy-makers, researchers, marketers and consumers will be the only way to imagine fashion lasting into any kind of new century for humanity. I think we can do it – I really, really do.

Microscopic Art by Daria Fedorova @dashaplesen

With a ban on textile destruction by the EU, I predict the increasing presence of upcycling in the fashion industry. Textiles will have to be diverted and we can expect spaces like recent LVMH winner Julie Pelipas’ ‘Bettter’ as a vision of the future, or South Africa’s Alexa Schempers and her brand Rethread. On the surface, ‘Bettter’ reads like every slouchy-minimalist fashion girls dreams; a subversion of men’s suits are the brand’s signature, with Julie one of Eastern Europe’s fashion darlings – the suits are deadstock fabrics, and Pelipas intends to harness the brand as an ‘scaleable upcycling system’ to integrate the practice of reworking deadstock garments into the garment construction process. In my conversation with Alexa Schempers, her strategy for solving fashion’s waste problem consists of three categories, which she described, “I think because we have three different categories – upcycling, ready-to-wear and vintage – it’s kind of like running three, micro-systems under one business. As a small business, figuring one thing out is difficult enough, so the variety is quite challenging. Zooming into each process offers its whole host of challenges, but I think upcycling is perhaps the most unique frontier to face in terms of production. We use vintage garments, taking them apart and re-designing them, and being able to offer this as a product hinges entirely on the availability of supply. There are not many people willing to work in that method because it’s non-traditional, and you’re required to almost think backwards. Then, being able to scale upcycled concepts and designs so that we can offer varying sizes, and not just make once off pieces.” This kind of market-analysis and understanding that educating consumers is vital renders Alexa as a leader in instituting upcycling as a normalised (and chic) practice.

Collective change is a difficult road to embark on when our individualism is fostered under the current political and economic systems that we inhabit. There is brilliance and foresight occurring, and I do believe that the telling signs of climate change (heatwaves, wildfires and so on) are going to prompt even more drastic action by governments around the world. Whether it’s too late, as I sometimes nihilistically assume, is really not the point – our human drive to problem solve and to design will hopefully avail. Fashion has to look at its waste problem with even more microscopic concern than bacteria growing in petri dishes; collaboration with other industries, policy-makers, researchers, marketers and consumers will be the only way to imagine fashion lasting into any kind of new century for humanity. I think we can do it – I really, really do.

Written by: Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za