“The Milk of Dreams takes its title from a book by Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) in which the Surrealist artist describes a magical world where life is constantly re-envisioned through the prism of the imagination. It is a world where everyone can change, be transformed, become something or someone else. The exhibition The Milk of Dreams takes Leonora Carrington’s otherworldly creatures, along with other figures of transformation, as companions on an imaginary journey through the metamorphoses of bodies and definitions of the human.

This exhibition is grounded in many conversations with artists held in the last few years. The questions that keep emerging from these dialogues seem to capture this moment in history when the very survival of the species is threatened, but also to sum up many other inquiries that pervade the sciences, arts, and myths of our time. How is the definition of the human changing? What constitutes life, and what differentiates plant and animal, human and non-human? What are our responsibilities towards the planet, other people, and other life forms? And what would life look like without us?

These are some of the guiding questions for this edition of the Biennale Arte, which focuses on three thematic areas in particular: the representation of bodies and their metamorphoses; the relationship between individuals and technologies; the connection between bodies and the Earth.” – 59th Venice Biennale curator, Cecilia Alemani.

I had never been to a Biennale – of any kind – until just recently, on a trip to Venice. I have been fortunate to visit both classical and modern art museums on my travels around the world, and attend galleries in South Africa – including the most recent Investec Art Fair in Cape Town. I wasn’t prepared – both physically and emotionally – for the sheer magnitude of this showcase, taking place in the Central Pavilion (Giardini) and in the Arsenale, which includes 213 artists from 58 countries, until November later this year. It is common practice for art shows to be unified through a thematic concept; whether individually ascribed by or to the artist, solo or in a collective, group exhibition – and in the framework of a Biennale, the showcase is divided into “pavilions” that are founded by a country. In this strange, often antithetic-to-the-anarchy-of-artists dynamic between artist’s, their nationalities and the construct of borders; the concept of a Biennale in this regard is at its most base level, proliferated with nuance and complexity. The Milk of Dreams, the central theme of the Biennale this year in 2022, was an epic portrayal of stark variation of contemporary art filtered through the consciousness of artists, their feature alongside their peers, the context of their representation for their country, their country’s position in the global context, and finally – the innate, shared experience of being a human being on one, single planetary body of the earth.

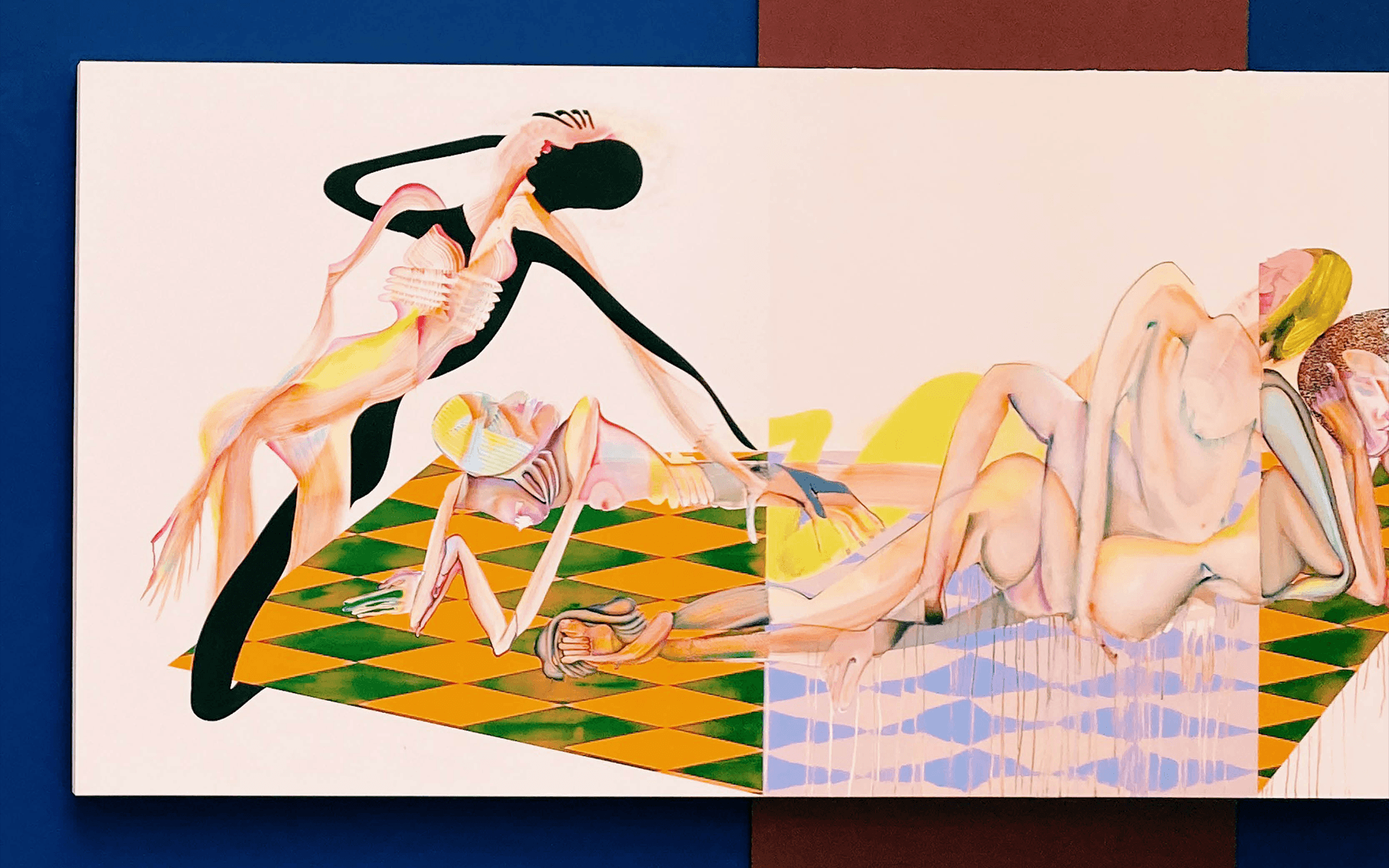

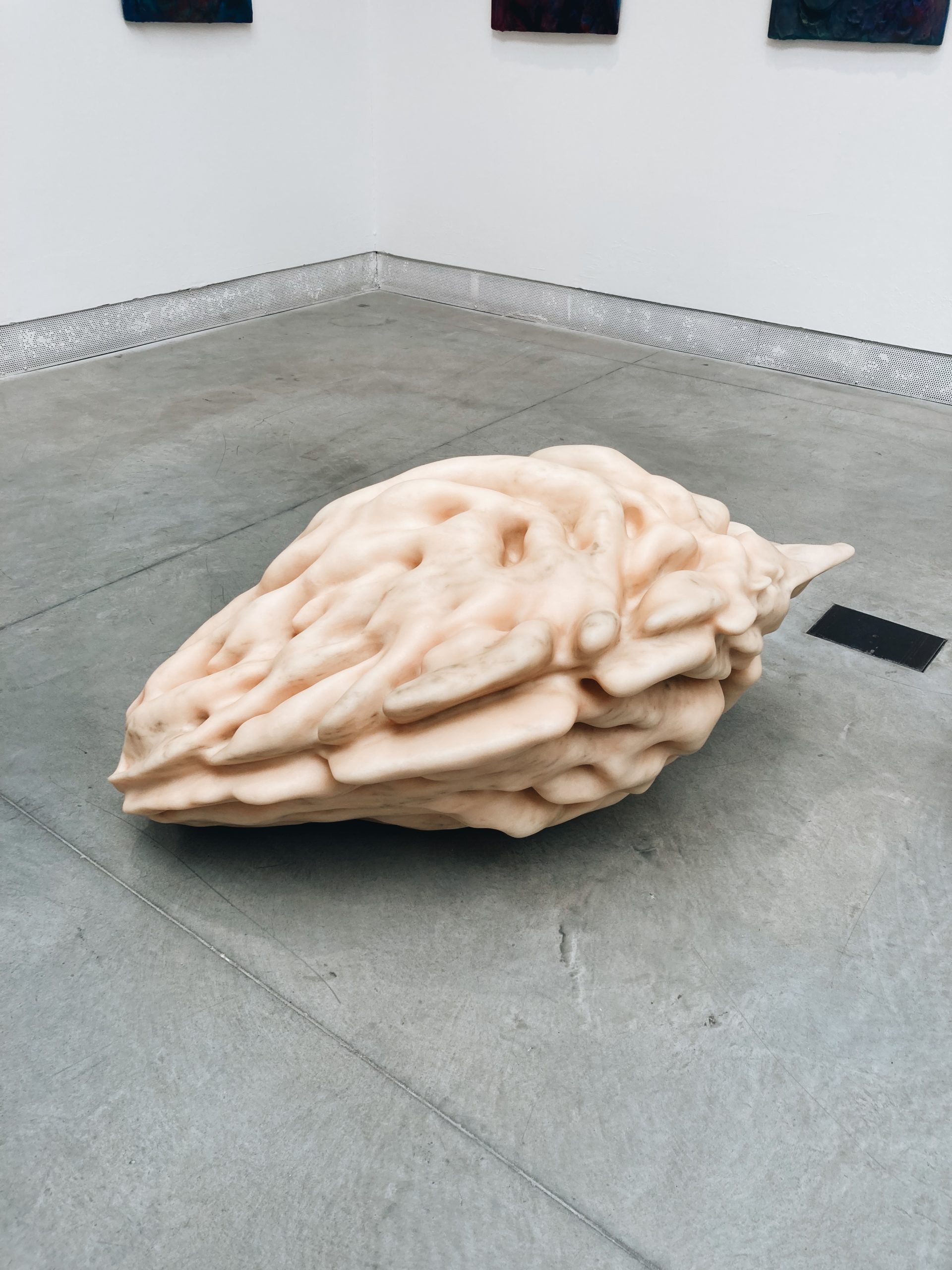

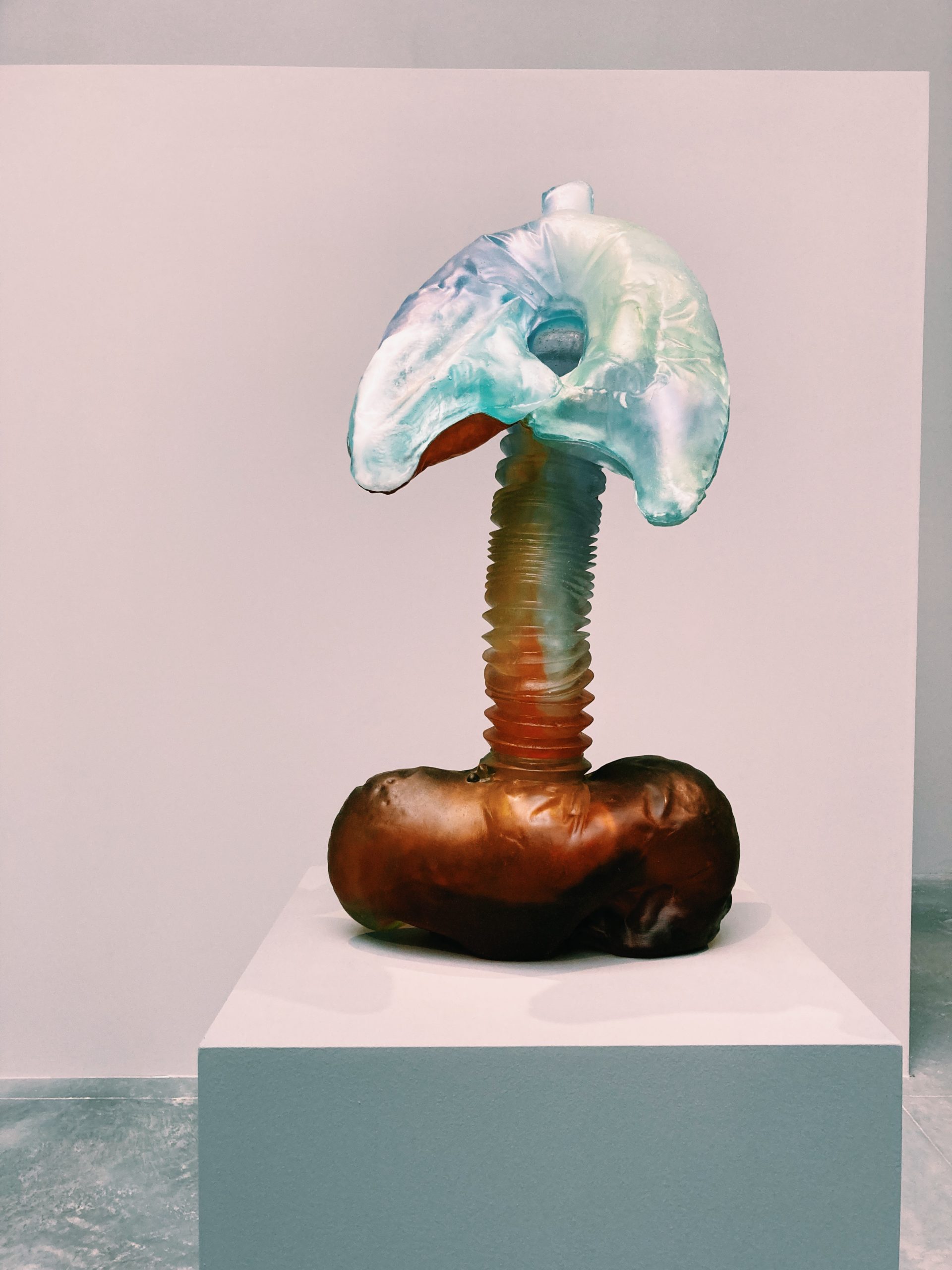

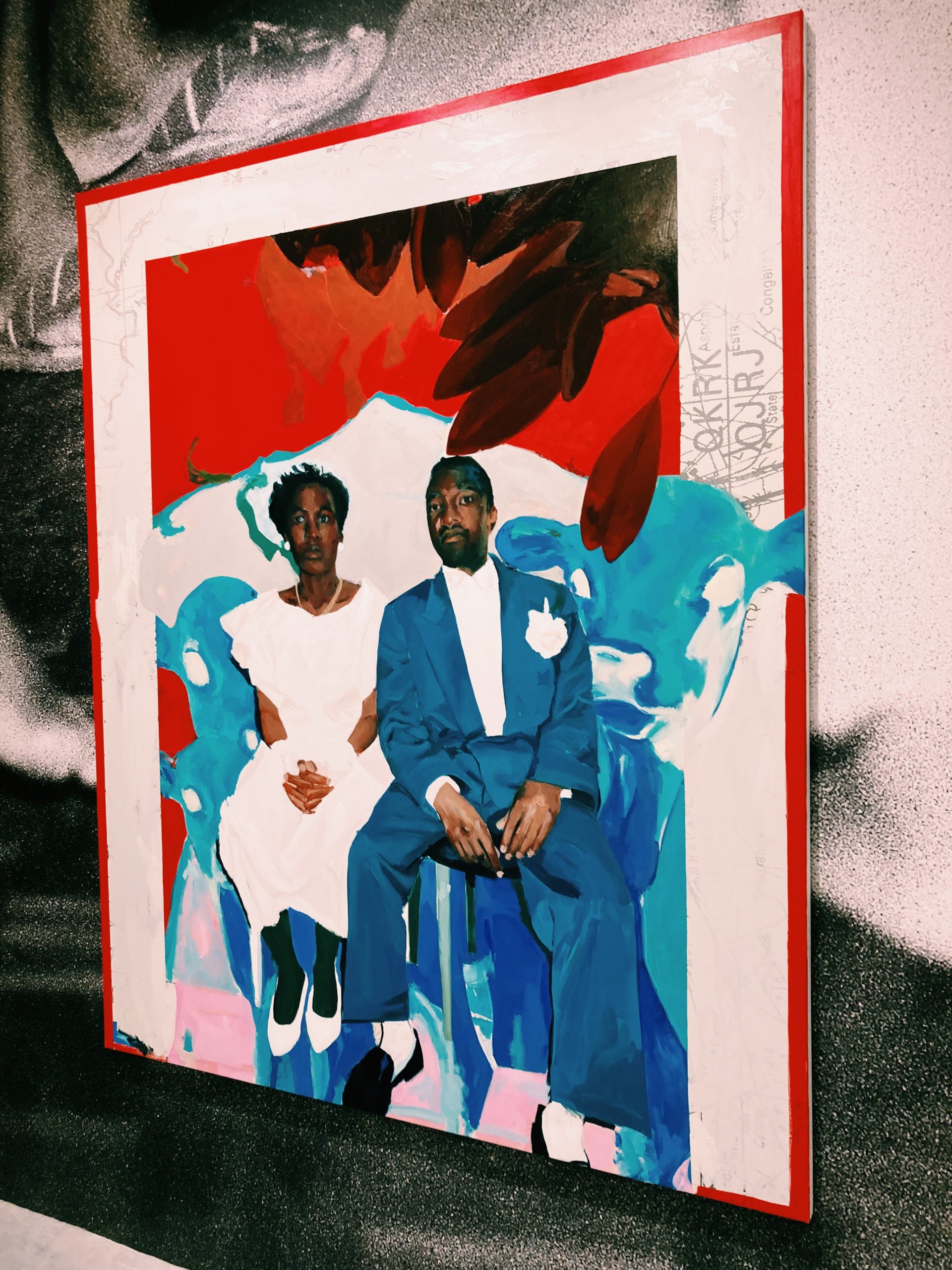

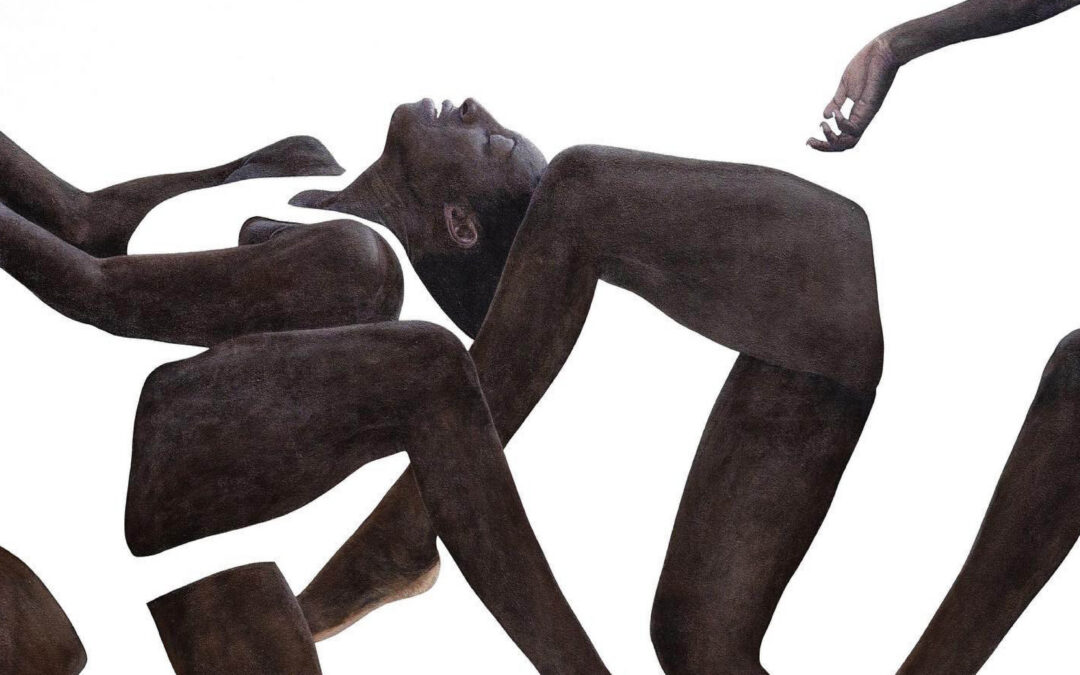

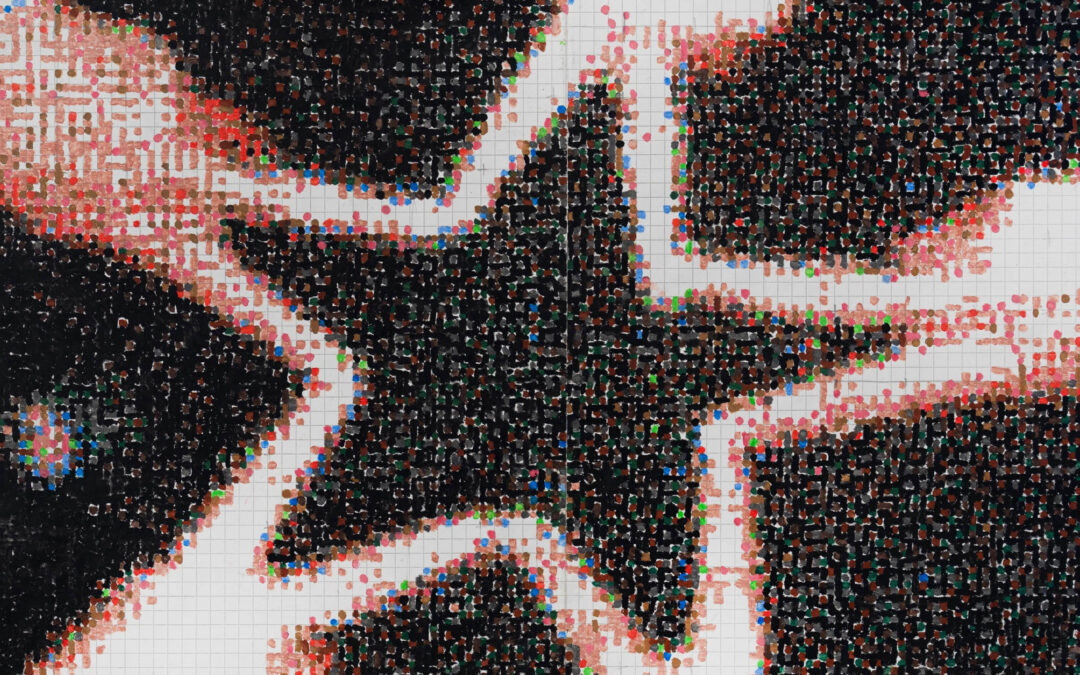

Walking through the varying arms of the Gardini and Arsenale – which, in hindsight, is something to do over two days rather than in one – I was struck by the interpretations of the curatorial theme that could be lensed in such a multiplicity of ways. A reminder that within each human being, lies an innate originality, vulnerability and ingenuity. The central space was breathtakingly curated, enriched by the contribution of female artists – with curator Cecilia Alemani stating that her intention was for the central exhibition to ‘not be built around systems of direct inheritance or conflict but around forms of symbiosis, solidarity and sisterhood’. I couldn’t believe my eyes at the work of Indian sculptor Mrinalini Mukherjee’s beings of divinity – massive woven sculptures depicting beings of divinity, imposing in their structure with an energetic imprint of grace. Kudzanai-Violet Hwami’s paintings depicting spiritual ceremony and a Shona wedding ritual was pivotal in conveying her upbringing in Zimbabwe and South Africa – weaving together themes of magical realism, Afro-Futurism, a Shona cosmology and community, nature and humanity. Hannah Levy’s obscure, almost repulsive objects denoted both a reference to furniture while showcasing a sensibility of alien-life forms; an egg sac balancing on three arthropod-like steel legs, an oversized peach pit like a discarded organ, and a tent in the fashion of a thin membrane. The use of silicone in a quiet shade of pink contrasted with steel reminded me of musician Sevdaliza’s work in her music videos – that brings forth an image of cross-planetary inquiry; perhaps life beyond our planet will have to be both beautiful and bizarre?

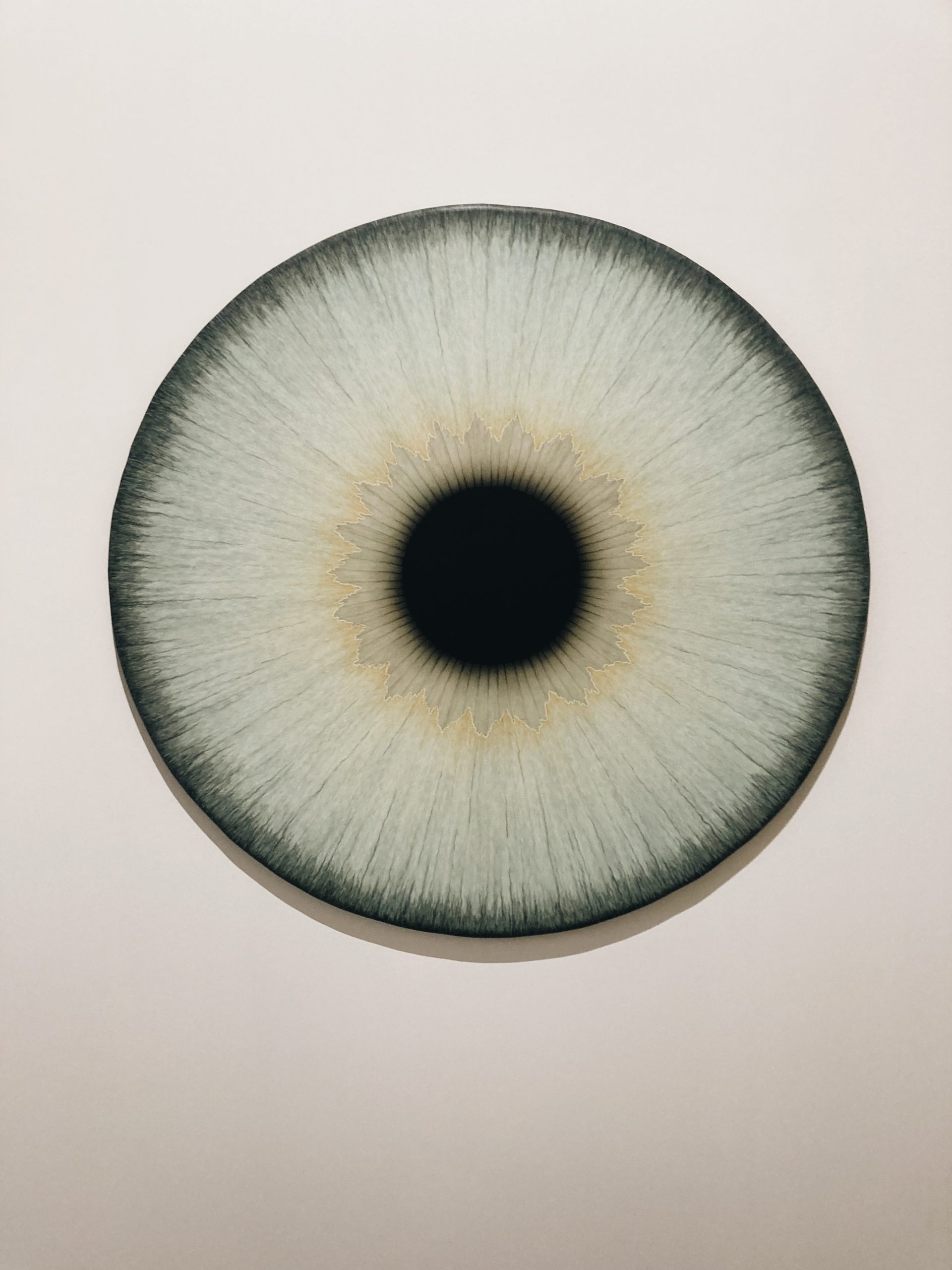

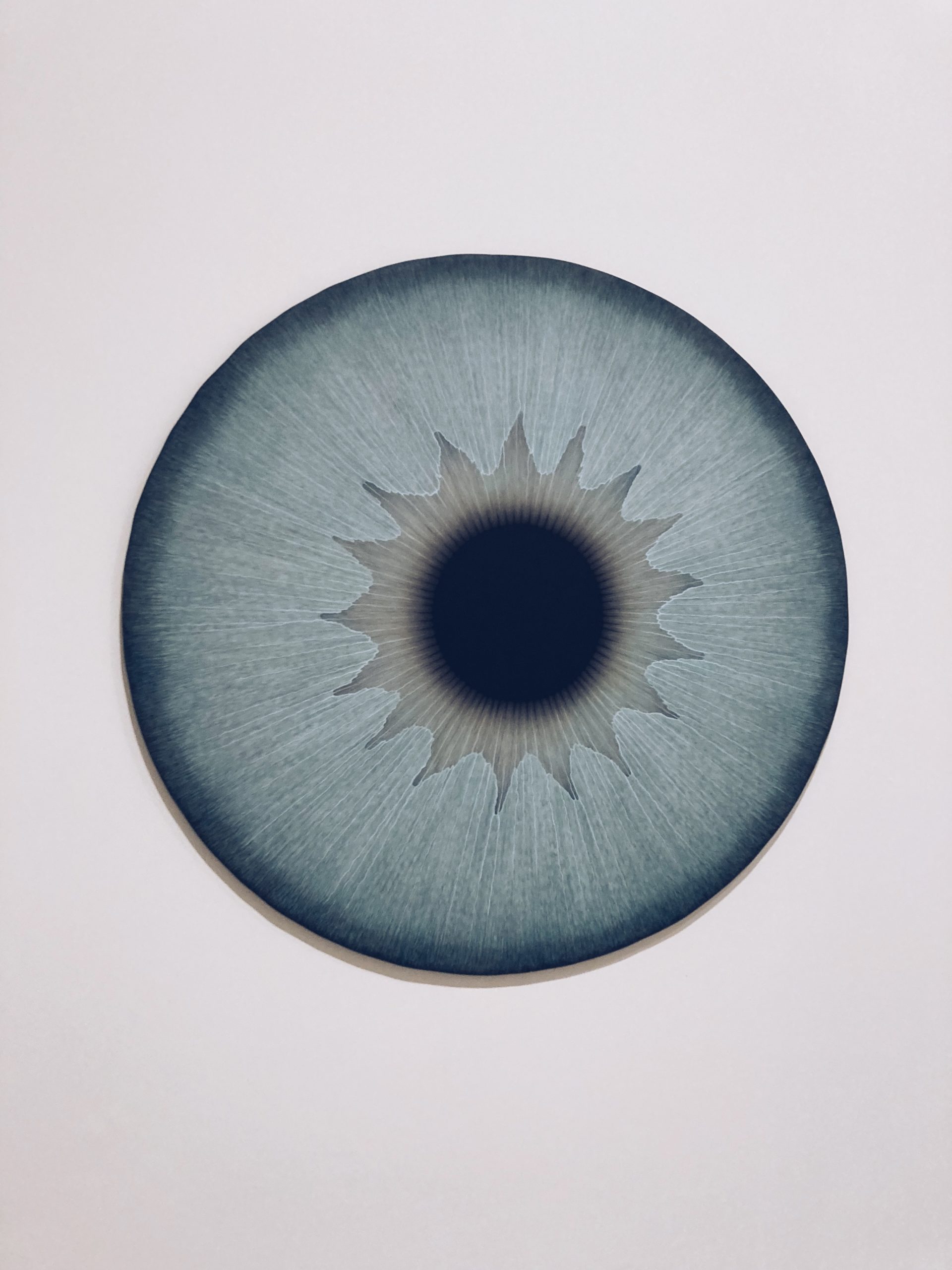

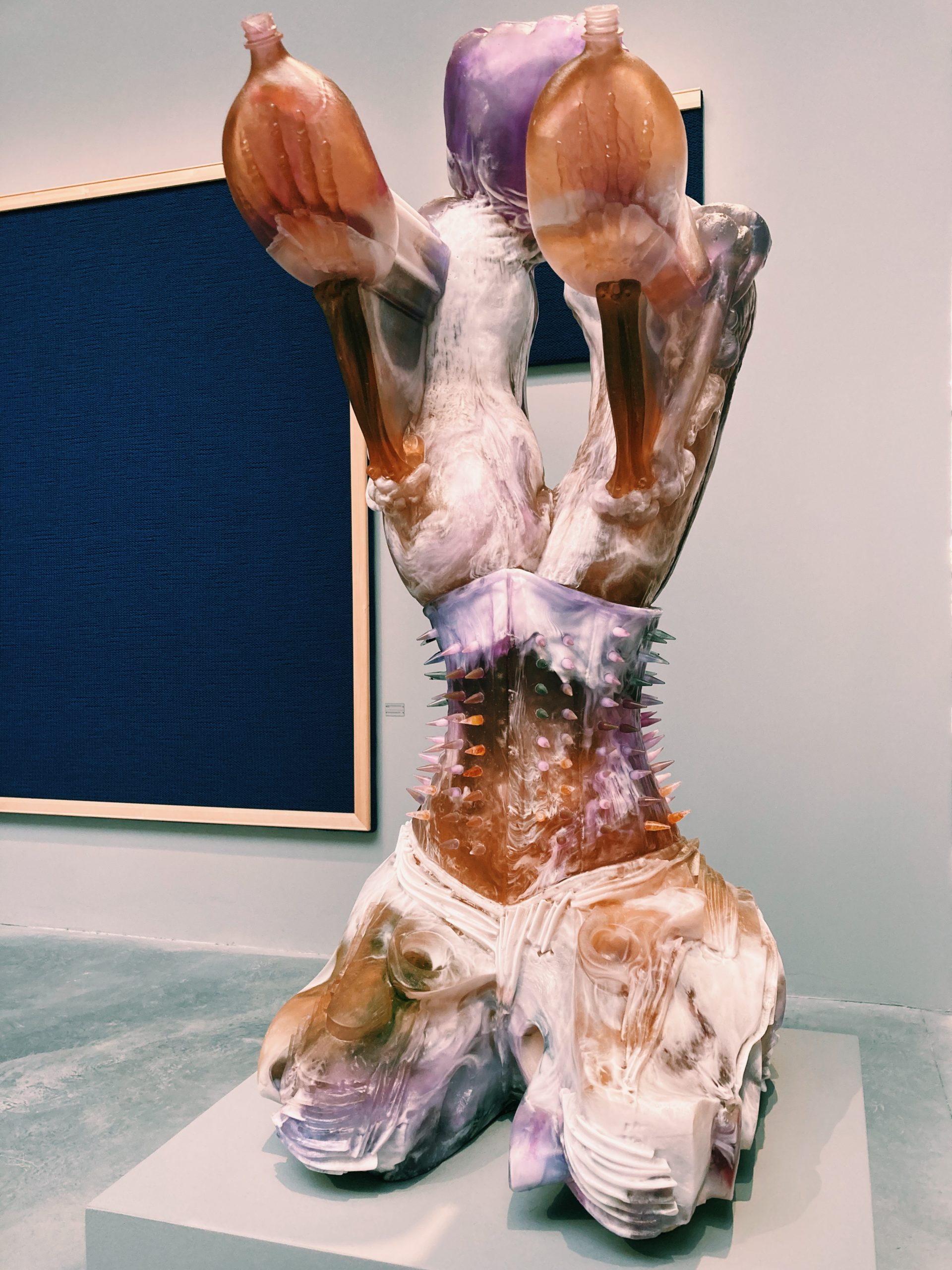

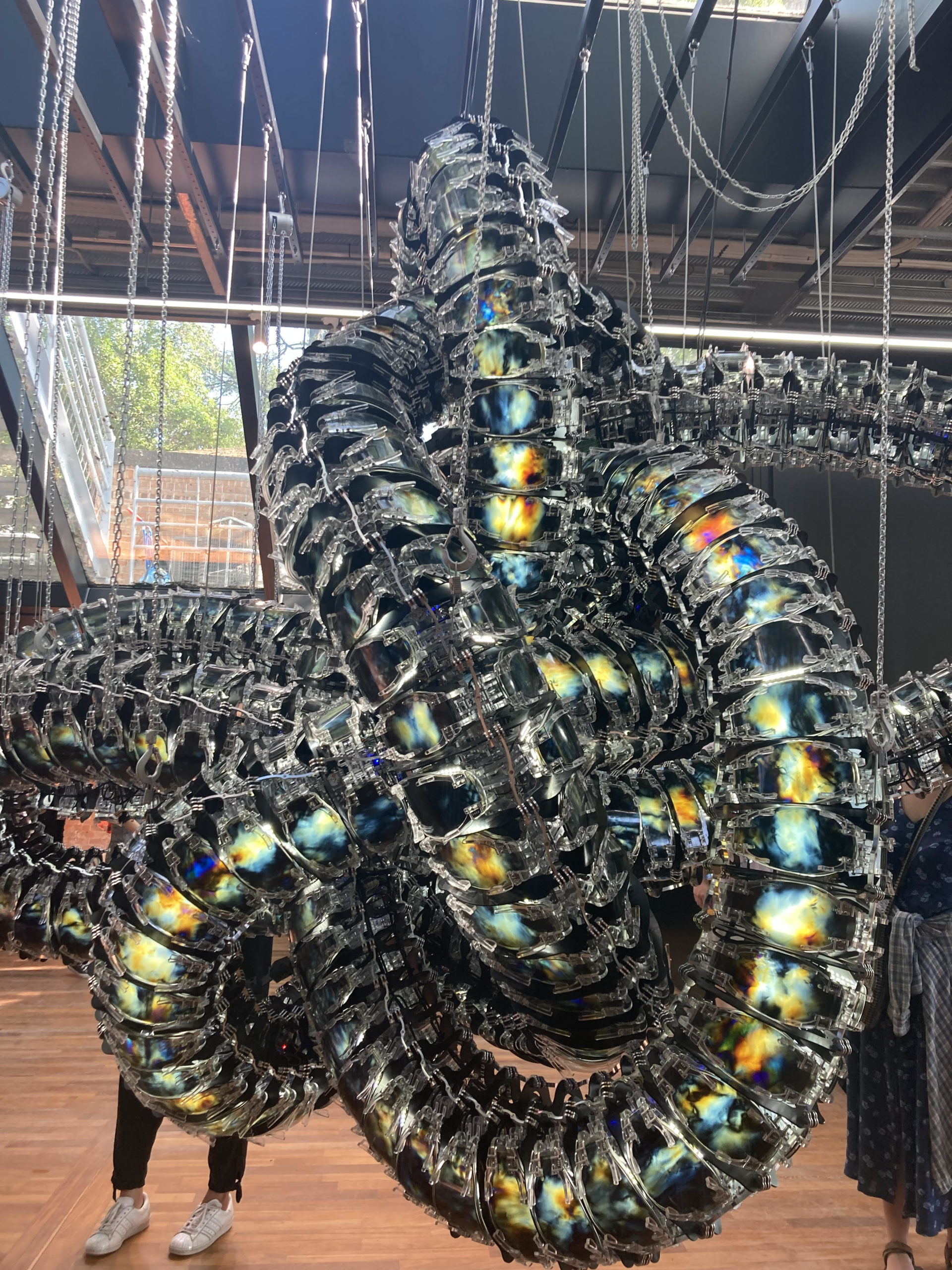

Some of the most striking pavilions (although each one could stand alone) was Hungary and South Korea. Zsófia Keresztes’ showcase for Hungary was an almost psychedelic, certainly surrealist depiction of identity (and its many, oozing and contorting forms) built as sculptors, layed with pastel shades of intricate tiles and mirrors. Each “established’’ country that has built a pavilion over the years tend to reflect their entry way into the region of global politics, as determined by Europe, which is interesting when seeing the totally abandoned Russian pavilion, the modern pavilions of countries like Estonia and Hungary – and the separation of Finland from the Nordic pavilions of Sweden, Norway and Denmark. There is a sense of qualifying for a seat at the table – and some of the curated pavilions, like Estonia, used their space to pose these questions of colonial sympathising for self-preservation, and a drive to uphold indigenous viewpoints like the Sapmí showcase for the Nordic pavilion by artists Pauliina Feodoroff, Máret Ánne Sara and Anders Sunna. South Korea’s three themes of The Swollen Suns, The Path of Gods and The Great Outdoors mirrored an entangled labyrinth of machinery and materials reflective of the micro-world on earth and cosmic events. With the incredible kinetic “breathing” machine – engineering and art are showcased as a unified expression.

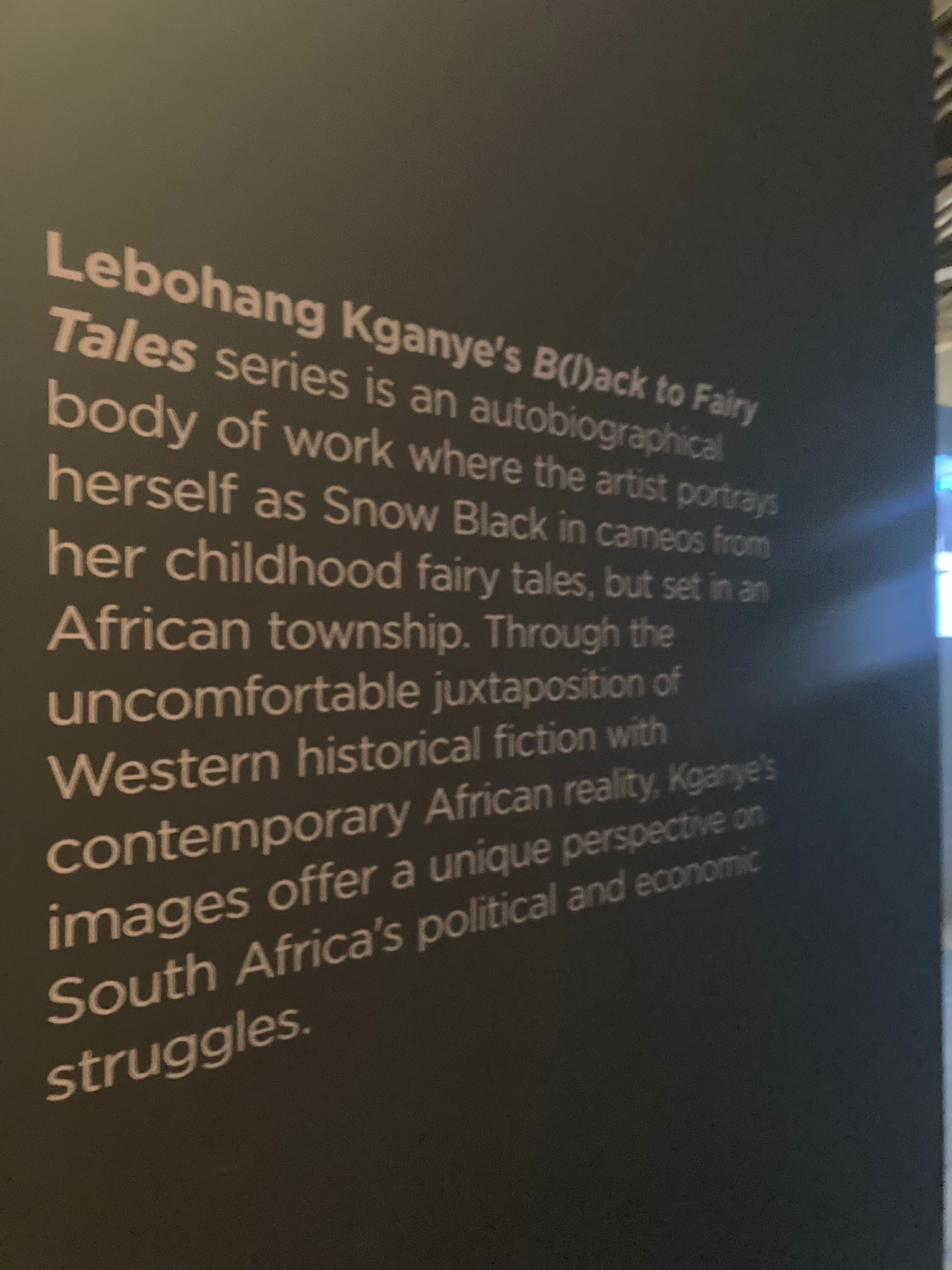

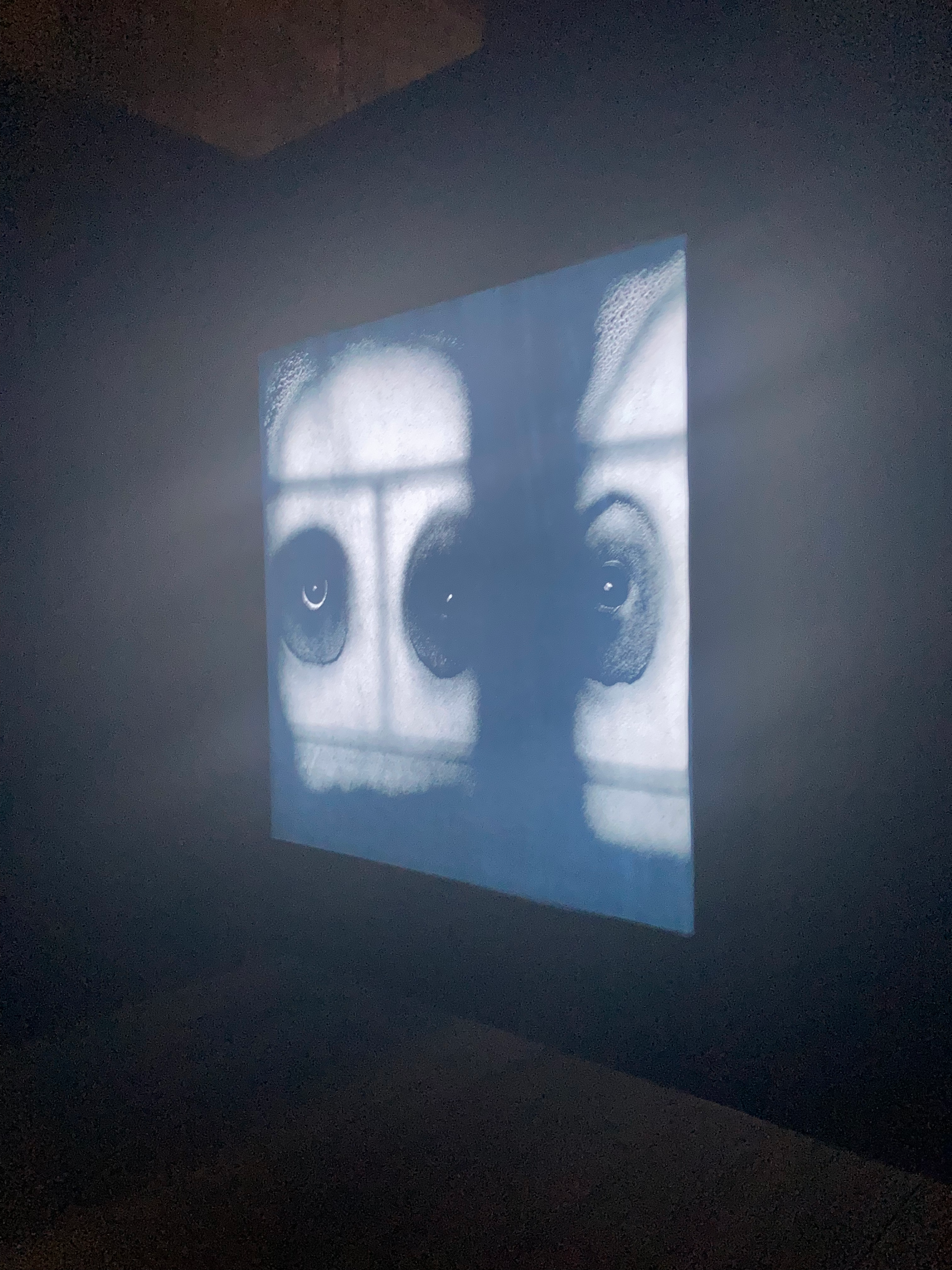

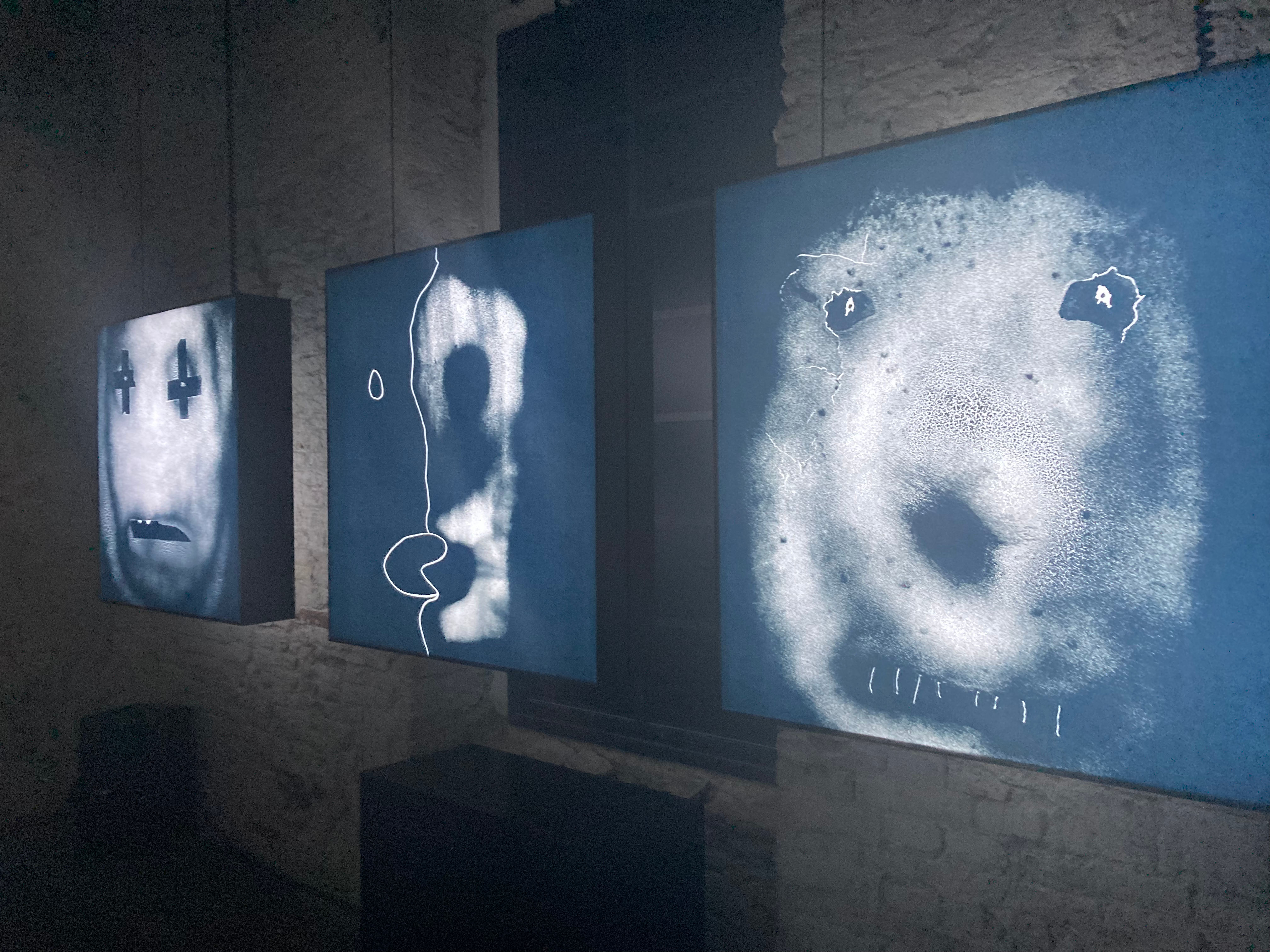

Lastly, our own South Africa showcased at the Arsenale section of the exhibition – called Into the Light, which included Phumulani Ntuli, Lebohang Kganye and Roger Ballen. Taking reference from the emerging into a new space or frontier, as South Africa as a nation and people are well acquainted with, the space was dimly lit contrasted by the artist’s visceral interpretations of identity, individuation and self-actualization. Personally, the showcase was wonderful to see – but perhaps with a bigger space and notable accessibility than where the South African pavilion was situated. This does not, however, impede on the quality of the exhibiting artists; and perhaps lends itself to the theme, too; of emergence, and rising up.

The 59th International Art Exhibition runs from 23 April to 27 November 2022