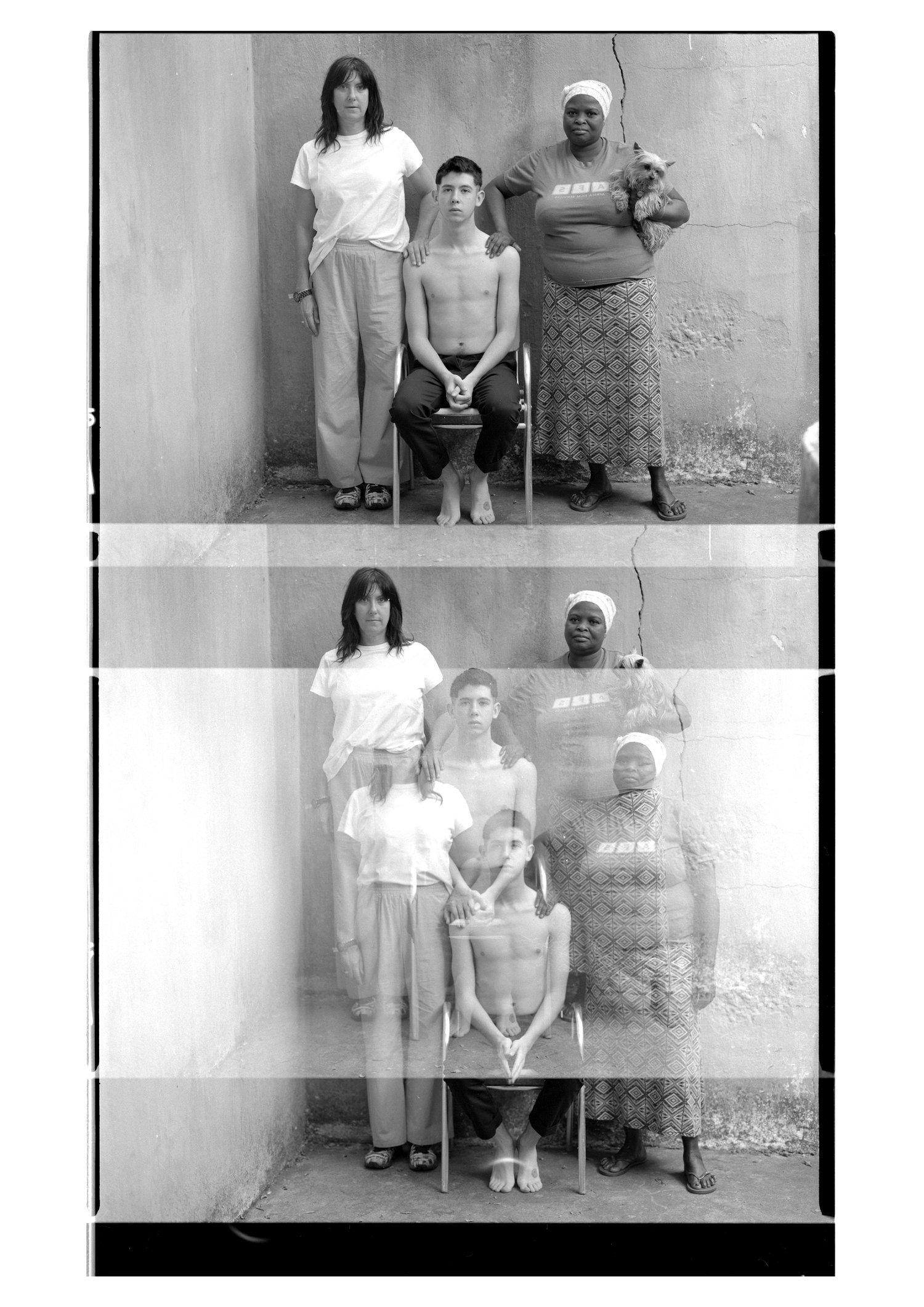

Dune Tilley was 17 when CNN asked him to participate in a photographic series for International Youth Day. In his commissioned self-portrait, Dune is perched on a chair between two women, a tender hand on either shoulder; the feminine forces that shaped him – his mother, and his second mother, Dune’s domestic worker. Embedded in the image is the precise dichotomy of South Africa; the response to CNN’s brief on what each young African photographer felt most concerned about in their country. For Dune, born some years after the cessation of apartheid, his subject was the disparity of his two maternal figures; the accompanying text reads, “These two figures, although in my eyes represent that of my motherly figures, in the eyes of the country (they) take on two very different roles and narratives. Although a similar age to my mother, my domestic worker was previously marginalised by the government, leaving her with no access to education and a low standard of living while my mother had access to a high standard of education and grew up in a quiet suburb. The wage gap between my mother and my domestic worker harps back to a disadvantaged majority due to the legacy of apartheid.”

To have a point-of-view as is so boldly required of artists is something we believe to be forged in the furnace of age; a slow, perspective kindled by all the pain and all the glory that the battle scars of time bestow upon us. Then, there are those who seem to have been born with those battle scars already emanating; Dune Tilley is one such being. At 22 years old, Dune holds a body of life’s (and living) work that impresses, with said point-of-view utterly responsive to what it means to be a young human being with vision that our elders either dream of, or fear. I was cautious to begin this story pinpointing Dune’s age; but I did, because I think the weight it symbolises outranks the need for discretion. When the keys are handed over to our generation(s), and people are welcomed for their talent and minds into spaces usually gate-kept – magic occurs, and a new cultural chapter is unleashed; such as the one Dune’s image for CNN beckoned for. The hope and possibility of South Africa’s future.

“I come from a very artistic family – it’s always been a big part of my life. Growing up, I was really encouraged to be creative, and to make things. I wasn’t into academia, but I found a lot of joy in art-making and design. With photography, it was when I got a film camera at Milnerton market, and I became obsessed with it. I got a job with a local nightlife company to shoot events following that; and I had a fake ID, obviously. So from 15, I was shooting nightclubs, and through that I started finding unique individuals. Nightclubs are the perfect place to see firsthand how people really are, and that encouraged the documentary-style reportage that began after that. I’m not really sure how, but someone at CNN saw the work I was doing and invited me to submit an image, as a young, rising photographer in South Africa. That was a big stepping stone in my career, from amateur and into a more professional space.” Dune says in our conversation, and it’s a theme that continues as we speak; Dune has worked ceaselessly since he was 15, grabbing hold of almost every opportunity presented to him. In the perfect blend of right time / right place, inner-determination, and a fixation for image-making; Dune’s honesty of image is derived from a childhood experience. On this, he says; “when I was much younger, between birth and eight years old, I was pretty much deaf. We only realised when I was in grade 2 or 3, when my spelling wasn’t where it was meant to be, and all throughout that time – my comfort was picture books. I have always felt safer visually. After CNN, it really emboldened me to take photography a lot more seriously. I had some amazing mentors, too – who I begged to let me assist them. Sweeping studios and building lights, that kind of thing.”

After high-school, Dune found himself a long-term documentary gig with a South African band, an experience that taught him many, many things; namely, what it means to make images beyond qualms, and ultimately, when to let go. Working directly with Roger Ballen, an idol of Dune’s, the creative experience itself marked his development in many ways. While the project never came to full fruition, Dune was already on a fast-track to somewhere he couldn’t have known yet, saying “I think it’s important to hold things sacred in an industry like this, it gets so easy to justify your way out of any moral or ethical thought. You can spin yourself in a circle, but to create good work that reflects who you really are; you have to be prepared to be totally honest. I learned that fast and hard.” On the other side of this poignant teaching, Dune counts mentors such as Gabrielle Kannermeyer, Raees Saiet, Duncan MacLennan and Ashley Benn; all of whom welcomed Dune into the realm of making the kind of art that he was destined to make; the stories that must be told, “they all really allowed me an overwhelming amount of freedom and space to work creatively at a really big-scale, at a really young age, to become the photographer that I am now. I think people don’t understand how much impact it has to allow someone into a space to make pictures, and what it does to your own perception as to what is possible beyond age – beyond our preconceived notions of the requirement to be ‘professionally’ creative.” Adidas is notably at the forefront of these sentiments; and perhaps it is why it remains one of the most important brands in the world, today. Not only is Dune a long-time photographer of adidas campaigns; he is now an associate creative director for adidas South Africa through room studios. Talent is irrelevant to age, and adidas demonstrates their commitment to vision.

Dune is a self-confessed ‘yes man’ – someone who is known to venture into spaces and scenarios that others might resist. This grit and flexibility bore him his relationship with Ashley Benn, founder of Room Studio – together they share a tried, tested and mutual vision for making work that stands out as wholly reverant and exemplary of South African culture, design, creativity; basically, the anima that makes our country as spotlighted and coveted as it is today. This led to international work that includes Asics China, Spotify Russia, BMW, Mercedes-Benz – and then some. Dune says, “When Ash started Room Studio, I was in third year at university. We met up again by chance, and he was telling me about this avant-garde creative studio that he was cooking up, and I told him then and there that if he did – I would drop out tomorrow and join. Whatever that meant. I got the offer to join the team as a concept lead soon after that, and dropped out immediately. Room is the internal creative studio for adidas South Africa, so my focus is there entirely now. It organically transitioned into an ACD (associate creative director) reassignment, and that’s been about two years.“

Dune speaks of Room as he does about everything else; with clarity and affection, and the acknowledgement of his rare position – but this ‘rarity’ is only because of his age, I feel, and soon – it will be Dune’s work that stands alone as a testament to his purpose in this world. From our conversation, and the wild focus of all his images, Dune is no longer ‘emerging’ – but in his established professionalism, the future remains wide-open. We are enamoured in witnessing what will become of it.

Written by: Holly Beaton

Published: 9 December 2022

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za