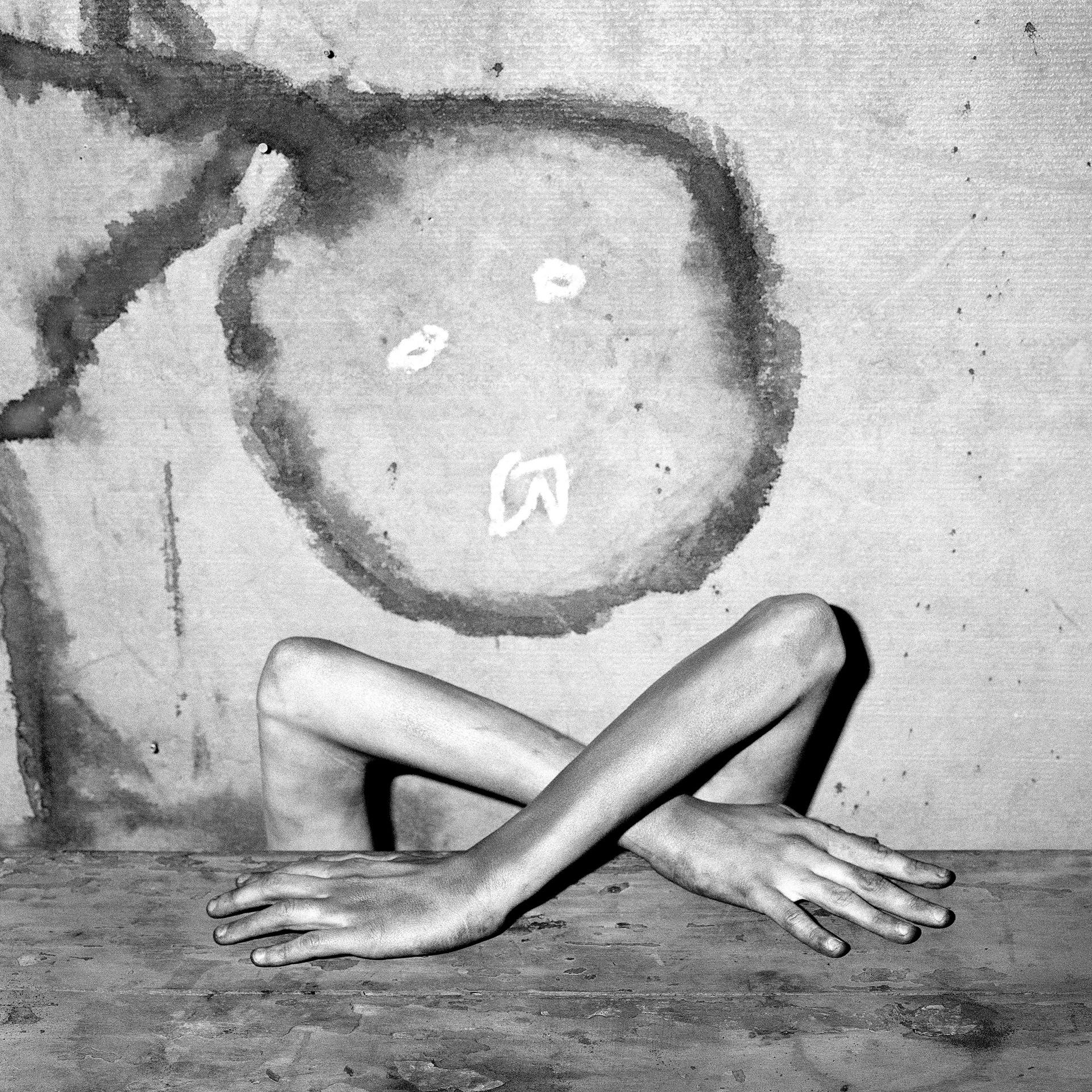

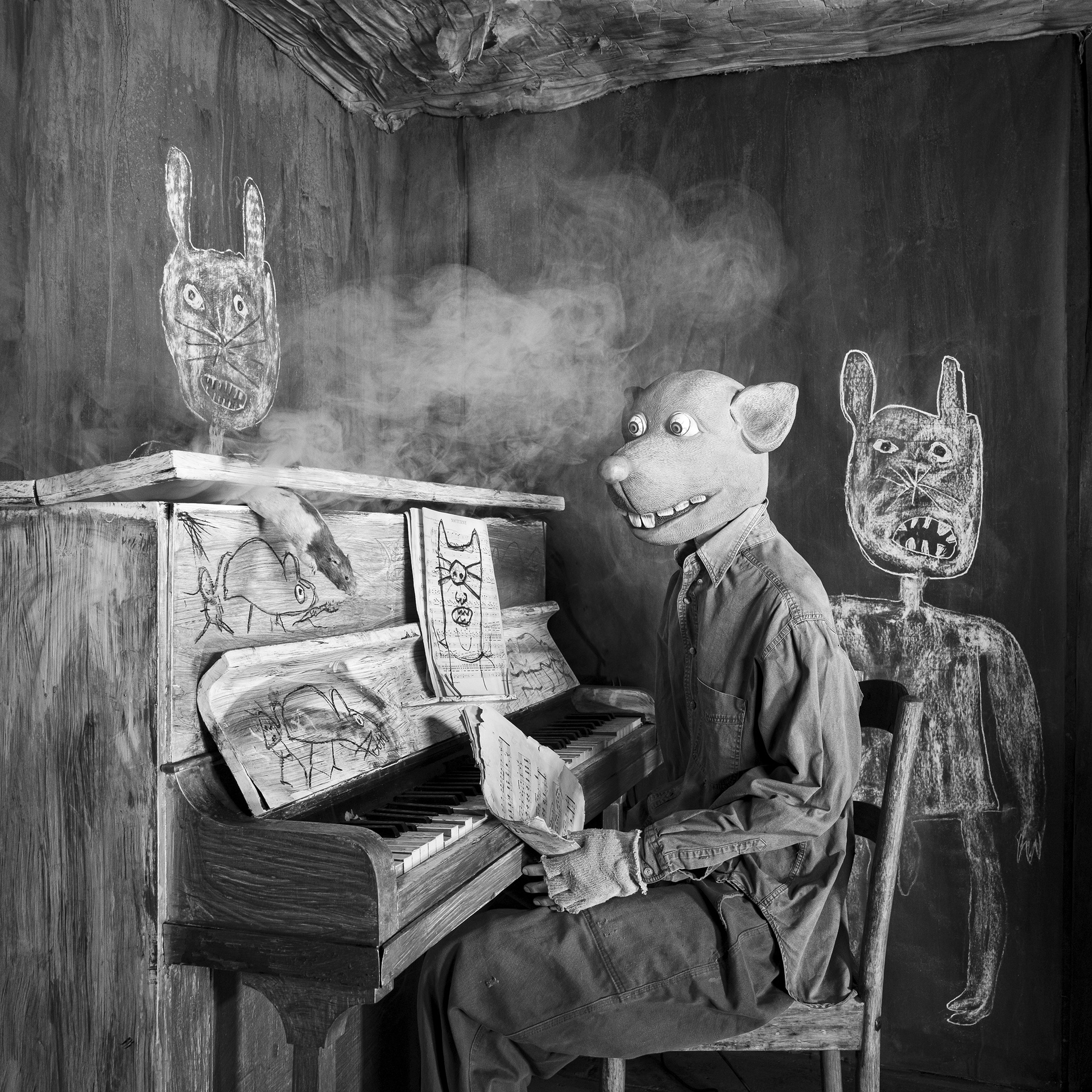

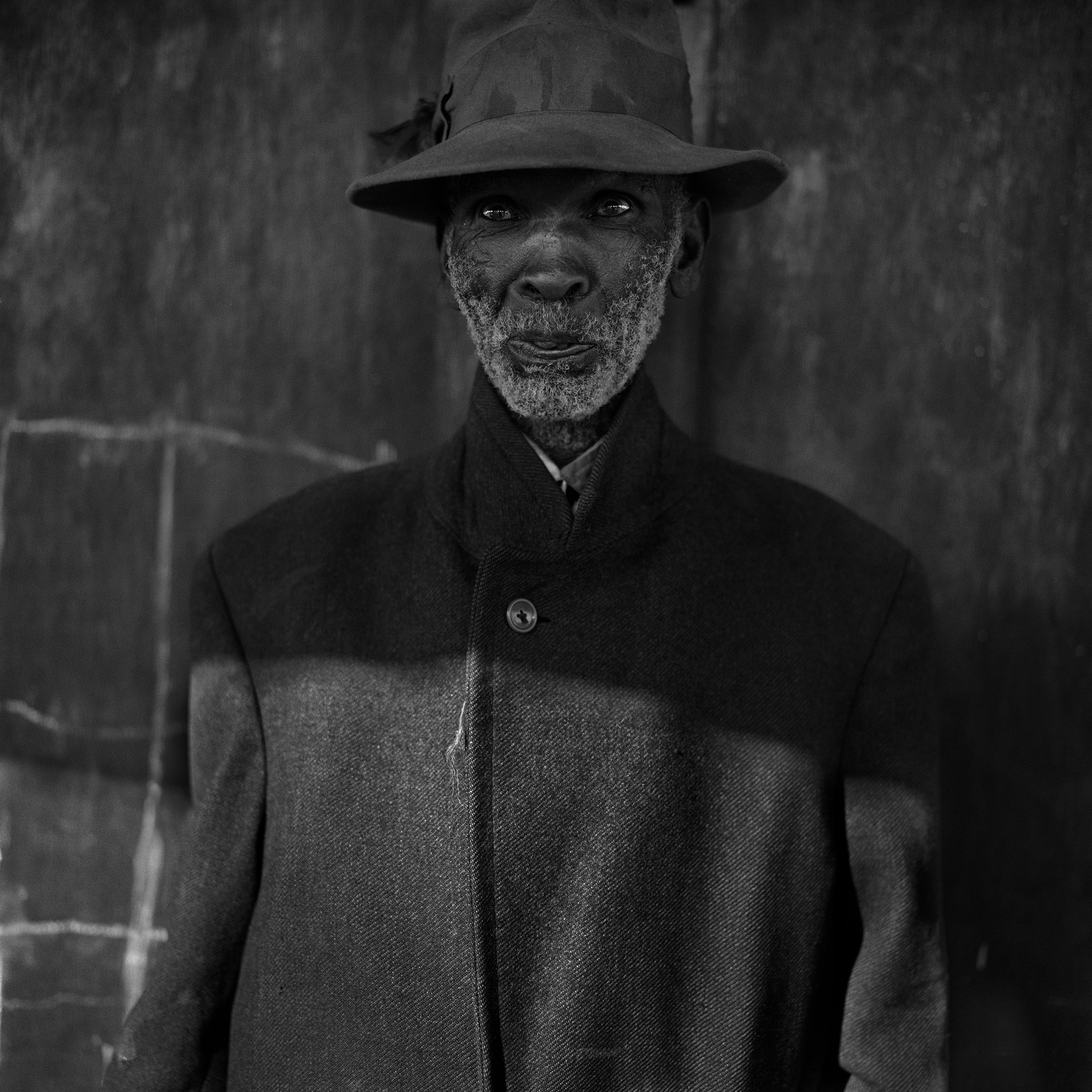

There are certain artists who possess a power and ability to expose us to what we refuse to see; and such artists tend to have the most visceral impact in the deepest recesses of our minds. Roger Ballen is one such artist – a vanguard, whose prolific career has spanned four decades – and of whom it would be impossible to distil into a single article or interview. In a style that is decidedly distinguishable as “Ballenesque” – a term eventually coined as Roger’s own descript recognition of of a personal articulation throughout the years – we, the viewers, are thrust into a contemplation that can be reactionary; felt in body, mind and spirit. Much of Roger’s work is suggestive of the unconscious asylum in which humanity’s collective mind space exists; outwardly, we are productive, consumptive, biassed and relentless seekers of comfort, growth and expansion. Inwardly, however, and as Ballen’s work reminds us, there is the haunting reminder of decay – imperfection as one of the only certain truths – and the ever-pervading presence of dualistic fixations. Good vs. Evil is a debate Roger refused to have a long time ago; instead, there just is all that there is. Liberating himself from such selective constructs has meant that Ballen’s path has been carved much like the ancient sediments that he observed as a geology student at Colorado School of Mines (a position that first brought Roger to South African in the 1980s) – a painstaking and curious excavation of his own mind, layer by layer.

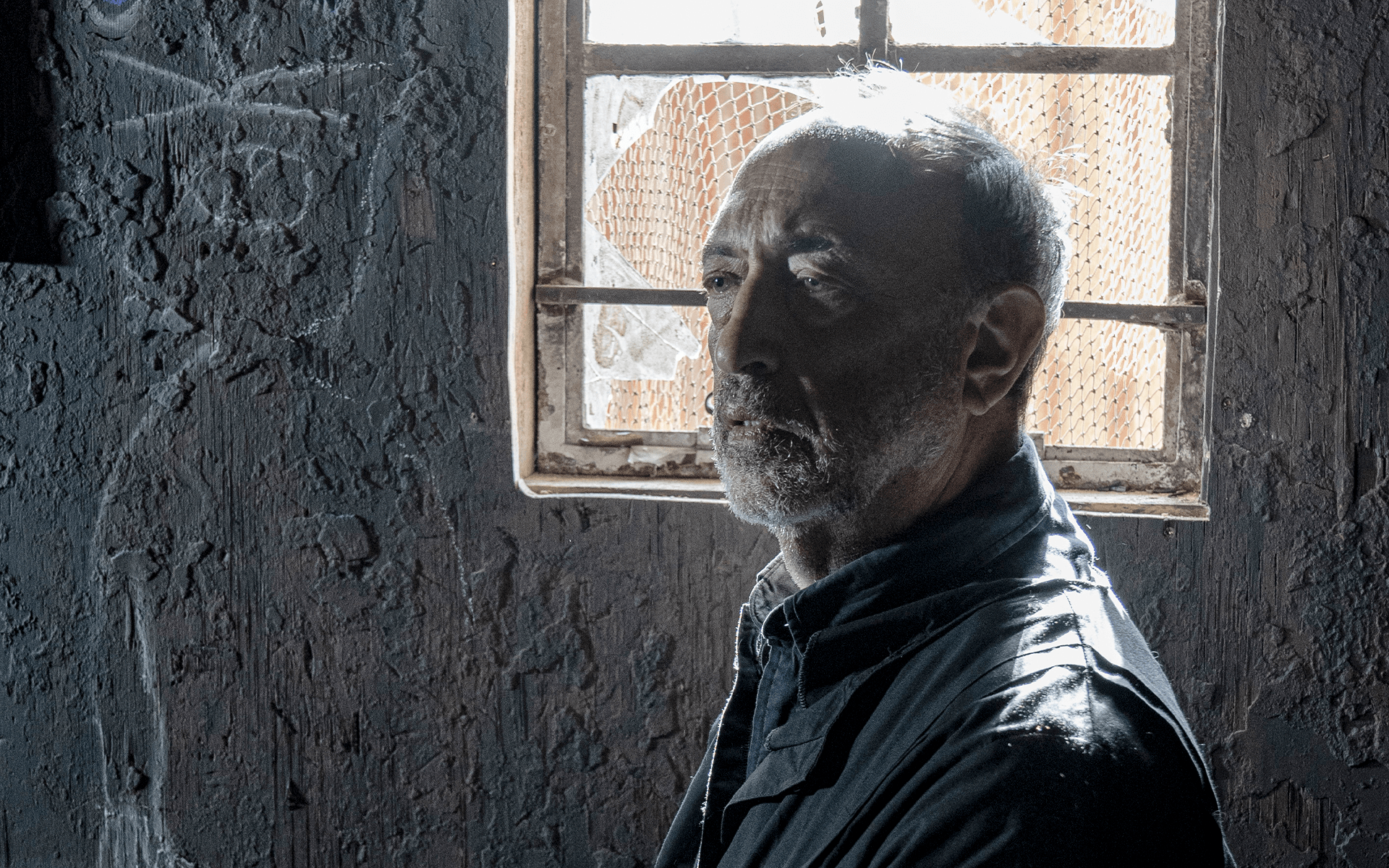

“I don’t know what’s stored up there in my memory, that’s the problem. I think that’s what keeps me moving forward. It’s a philosophical question, to wonder if you could unwind every moment that has happened in your life – would every moment be there?” Roger says on the matter of one’s own mind. Assuming the position of the everyday viewer, I wonder if he recognises the sometimes grotesqueness of his work’s theatrics, the psychological and existential nexus upon which his style exists; to which he says, “My approach has always been psychological, which I think started in the 70s with my first book called Boyhood. It was a trip I made hitchhiking from Cairo to Cape Town and then from Istanbul to New Guinea, and then South America. It was four years of trying to find my own childhood reflected in the world; and I was able to see this thread running through different cultures and lands as sentiments that speak to a shared experience of humanity. When I came to South Africa again in 1982, as part of my PHD training in geology, I started my first project here, Dorps. That was a critical moment for me – that beginning of that publication, ‘Dorps, Small Towns of South Africa.’” Roger reflects, on the metaphoric sense that underpinned that book – ‘’I went to Hope Town in the Free State, and I knocked on the door of a house, and going into that person’s home, I went inside physically and psychologically – and I rarely have ever taken a picture outside again. I started to find my motifs and techniques from then on.” Images from Ballen’s Dorps remain stark depictions of apartheid-era South Africa; the fascist state’s controlled and implemented division of people, subjugation across racial lines – and also, of class lines. Outside of the main city centres and economical melting-pots lay the dorpies; obscured and isolated even more so than sanctioned-against South Africa – itself a country modelled as a bizarre attempt at a utopic white supremacy.

On the seemingly harrow nature of these works, Roger says; ‘’I always say that in nature, there really is no beauty or ugliness. The darkness and light are not oppositional, they just are what they are – expressions of a wider whole. I think what we are dealing with in human society and in our psyche’s, is a permanent state of repression. A repression of the primacy of our instincts, and how deep our unconscious goes. So, there’s nothing really dark about what I do – but it seems to affect people’s psyche because they’re in a state of repression, and so desire order or predictability. Our obsession with attractiveness, spurred on by Hollywood and mass media machines, has made us too easily recoil at discomfort – whether aesthetically or otherwise. I think a world like mine, which is very concentrated, pierces through that repression and makes people somewhat anxious. From a Jungian point of view, the word “dark” would be a side of the Self – so I’ve come to learn that my work has that quality that aims toward getting through repression and denial.“ This inquiry into the Self is as integral to human’s and history as the very earliest variations in our biology; we have been wholly dependent on such endeavours as a propulsion through the ages. Art is then – absolutely essential to the human experience, if not the core of human experience itself; ‘’The work of an artist is an attempt to define the Self.” Rogers says, ‘’and there is never a conclusion to this work, either. You’re always finding bits and pieces stored in various crevices. That’s the problem with language, too. Semantics are restrictive and just our attempt to convey meaning or communicate – but I don’t think we can ever explicitly convey the entirety of what our minds conceive.”

Roger’s own stylistic language, Ballenesque, is so distinct that it led Die Antwoord to their own existential awakening post-Max Normal TV – how strange, we might think, that one of South Africa’s most famed and controversial music duos saw their own articulation through the lens of an American-born photographer, which set in motion a sequence of successes internationally, amid scandal too. Yet, this is the transcendent power of Ballen’s style – and again, its incisive quality that speaks to the very grit of living, whether here or elsewhere in the world. On the term Ballenesque, Rogers says ‘’I had to develop the confidence to call a book “Ballensque” and cement my own position as being unique or its own viewpoint. I think that comes with time, and dedication to my own particularities in my practice of art and photography. I think that has been an important stepping stone in my career, and although you can define it in other terms like “absurd” or “uncanny” or “theatrical”, combined – Ballensque is the best thing so far even with the confines of language to describe what I’m doing.” So indelible is this style that it caught the eye of avant-garde’s mother, Rei Kawakubo of Commes des Garçon, and in 2015 Roger’s work was featured in a AW15 showcase – signature ghoulish faces, drawn in charcoal, on the back of crisp white tailored jackets, “My only regret is not getting any samples, but it was great to have my work pulled into this world of clothing – which is not a realm I exist at all. I like how they interpreted it. It’s very rare that I would relinquish creative control – but they did a fantastic job with the collection and the subsequent installations in their stores, and Rei is exceptionally artistic herself.”

Among all the caveats to draw from our conversation, one of the most pressing had to be Roger’s black and white images of the infamous festival Woodstock ‘69 – the summer of love, as it where – a tear in the fabric of America’s tightly stitched together order and control; was he and his peers aware of just how momentous that moment was, when it was happening? Roger responds, ‘’That’s a good comment. It was the first large event of this kind, and it had an intense enthusiasm about it beforehand. The mood was changing in the states, and in the world – and I think this was a kind of pilgrimage to symbolise that, whether we really understood that at the time, I’m not sure. The fence fell down, and the entertainers that were there – mixed with the sense of being free – were powerful contributions to this overall push against society. Nobody expected it to become what it became, and its legendary status in our collective memory is in part due to our nostalgia, I think. It’s a landmark now of the 20th century, and as in everything in life – there’s the reality and the experience, and then how it’s interpreted by others.”

Right now, Roger is grounding himself – an unusual, but perhaps necessary step in his life. The grounding, or landing as it were, comes in the form of a physical space; Inside Out Centre for the Arts, in his chosen home of Johannesburg. Drawing on Brutalism, the building is a raw, materially-minimised archive for Ballen’s life’s work, set to also promote African photography and art, alongside educational programmes; “Our focus is Africa, and the work coming from the continent – as well as my work, all with a psychological component. I really like coming into my own place everyday, and to have a physical space to share more of the art and photography that needs to be shared.”