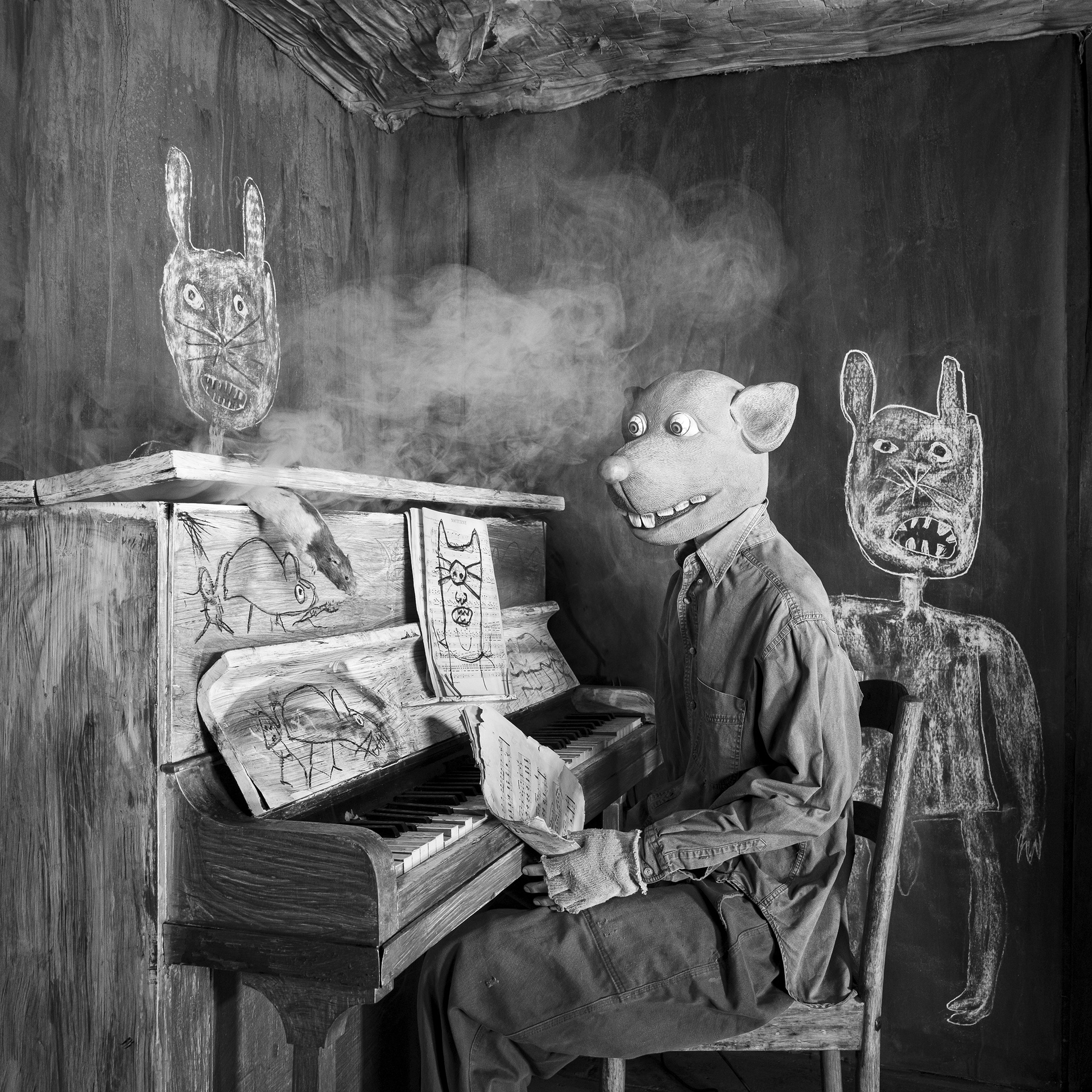

Boogie Vice Debut’s ‘Kariega Cruise’ On Amsterdam Based Label, Animal Language

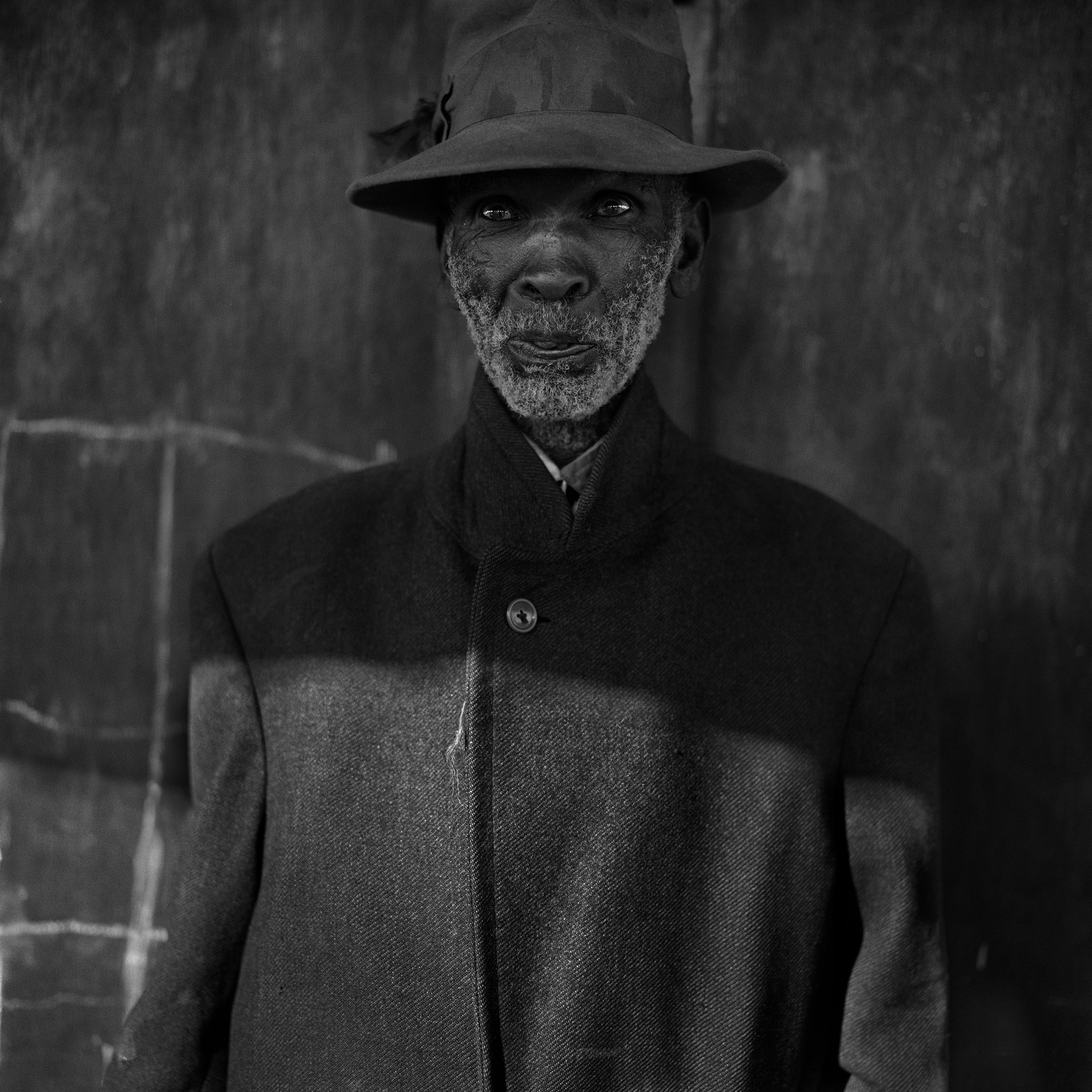

Hailing from Paris and currently living in Cape Town, Boogie Vice is a hyperactive producer and DJ whose music has been released by some of the biggest labels in the industry. His tracks have performed on Ed Banger Records, Get Physical Music, Circa 99 (Boston Bun), CUFF (Amine Edge & Dance) as well as Katermukke (Dirty Doering) among others.

Boogie Vice has a truly unique sound with influences of disco, groovy house and African tribal beats that have resonated with music lovers all around the globe. It’s this love for his music that has led to him covering a global footprint of live performances that span from Brazil to Argentina, Italy, Ireland, Russia, France & more.

Boogie Vice now makes his debut on Mason’s Amsterdam based Animal Language imprint. A label that is always willing to take a risk on the more eclectic sounds of the house scene. ‘Kariega Cruise’ is a pure distilled summer party vibe; like having the sun on your back and a mojito in your hand. It is a sonic stew of steel drums, snake-charmer-esque woodwind, pianos, and percussion. It’s a kitchen sink of a track that grooves as layers weave in and out creating pleasing musical havoc.

The track has already received DJ Support from:

Jamie Jones, Laurent Garnier, Robert Owens, Eelke Kleijn, Mason, Ida Engberg, Mousse T.

/// Stream ‘KARIEGA CRUISE’

Beatport

Spotify

Apple Music

Amazon Music

Deezer

Soundcloud

Tidal

Napster

/// For more Boogie Vice updates follow here

Recent Comments