Honestly, I could talk to Miles for hours – in our conversation, he is a wellspring of wisdom and a guardian of a particularly special time in South Africa. Post-1994, our country began to open up to the world – and suddenly, we were able to engage directly with the global occurrences in adrenaline sports, music, clothing and the acceleration of design and art, both digitally and on the streets. Yet, there is a decidedly South African way in which this zeitgeist was being met here – and skating had always been the craft of the misfits. Miles remincises on the earliest conception of Blunt, “I was living in the UK during winter and traveling to surf in the summer. After a long trip to Sumbawa, this beautifully remote island in Indonesia, I came back and felt like I needed a change of some kind. It was the mid-90s, and the internet had made a huge impression on me – especially being in the UK, it was already established – people had websites, email addresses. It was fully happening. It was at this point, late ‘96, where I was on my way to book a surf trip to the Canary Islands, which I had saved up for working 12 hours a day, 7 days a week on building sites and living in a pretty infamous semi-squat house in Lily Road, Hammersmith. On my way there, I saw an advert for a Canon camera – and the next thing I knew, I had bought the camera and was booking a ticket home at SAA. That was the camera I used throughout the early days of Blunt. That was the beginning of it – that decision to come home. I kind of knew things were going to take off here in the scene – a skate and surf scene that had a renewed sense of autonomy, freedom and a democratic vision.”

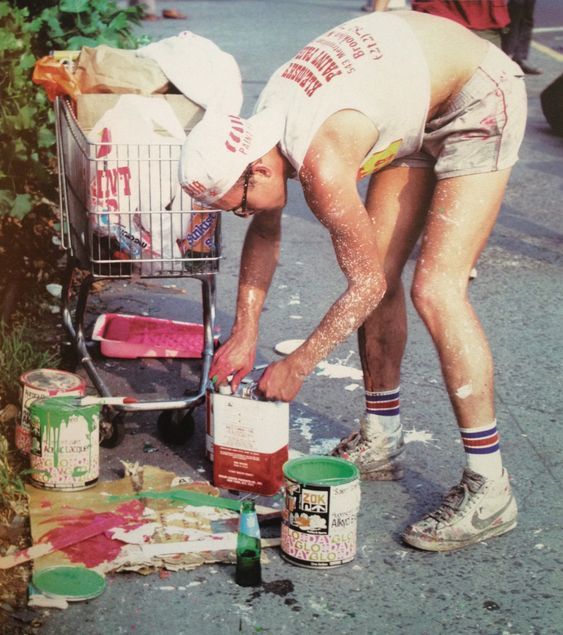

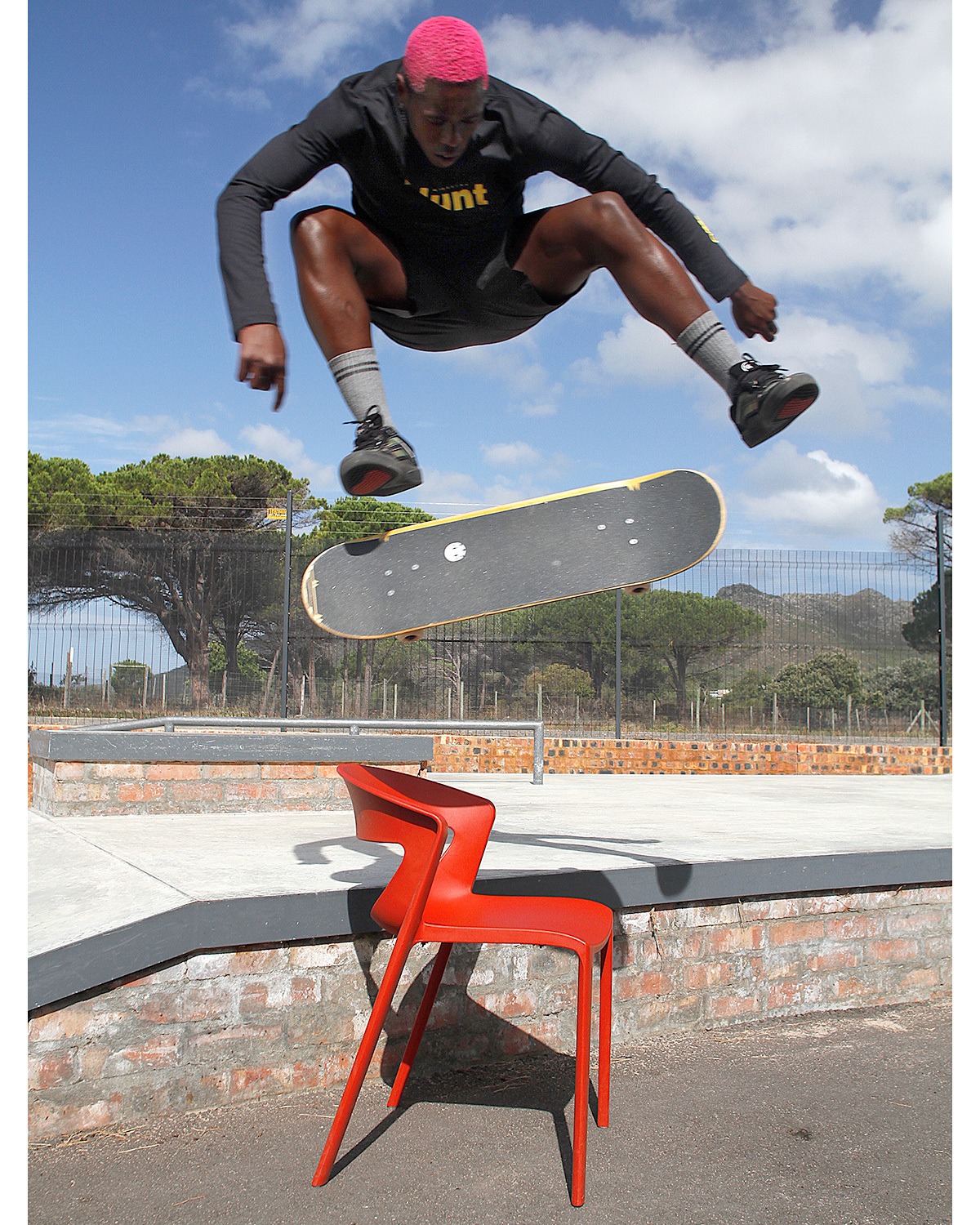

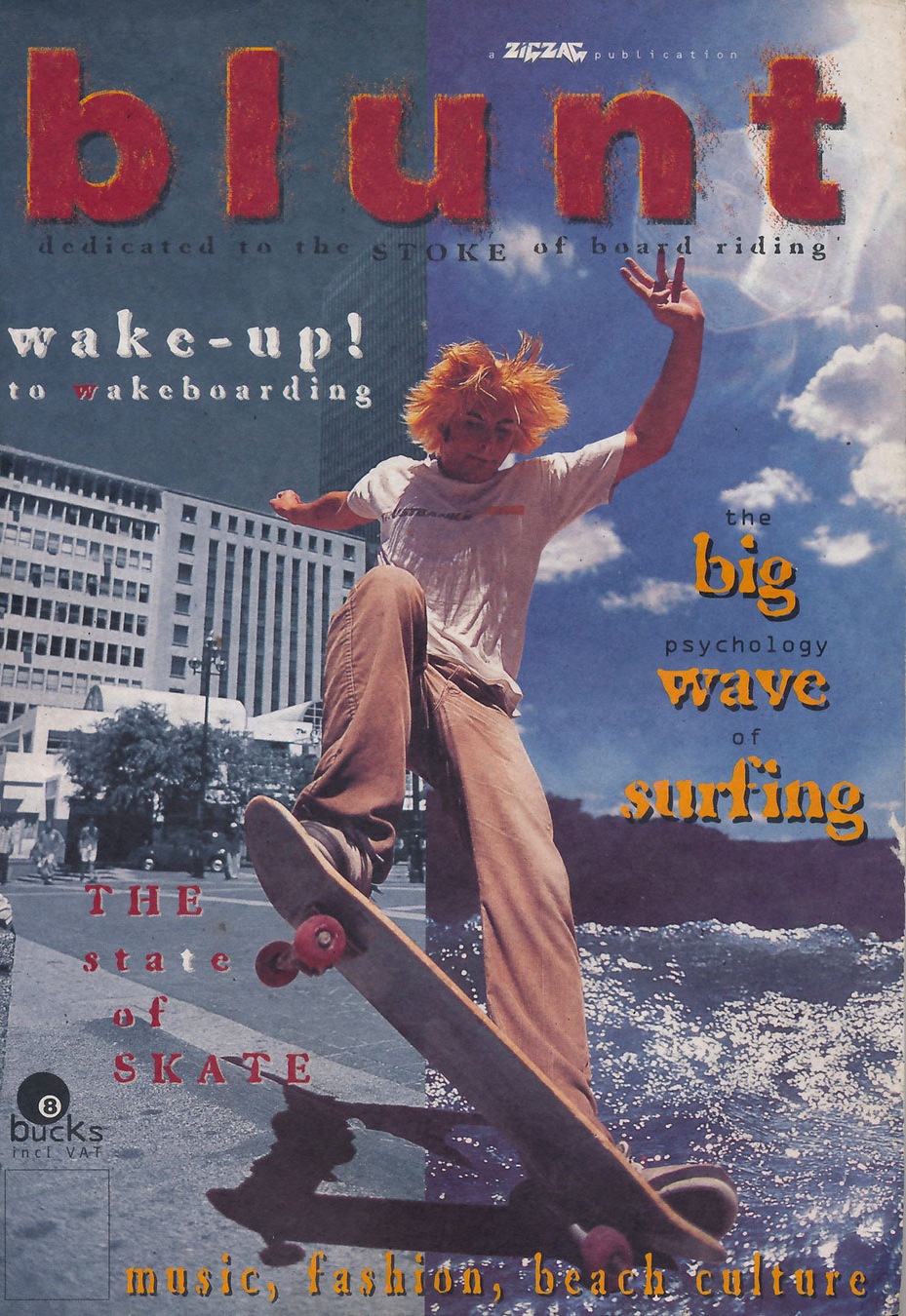

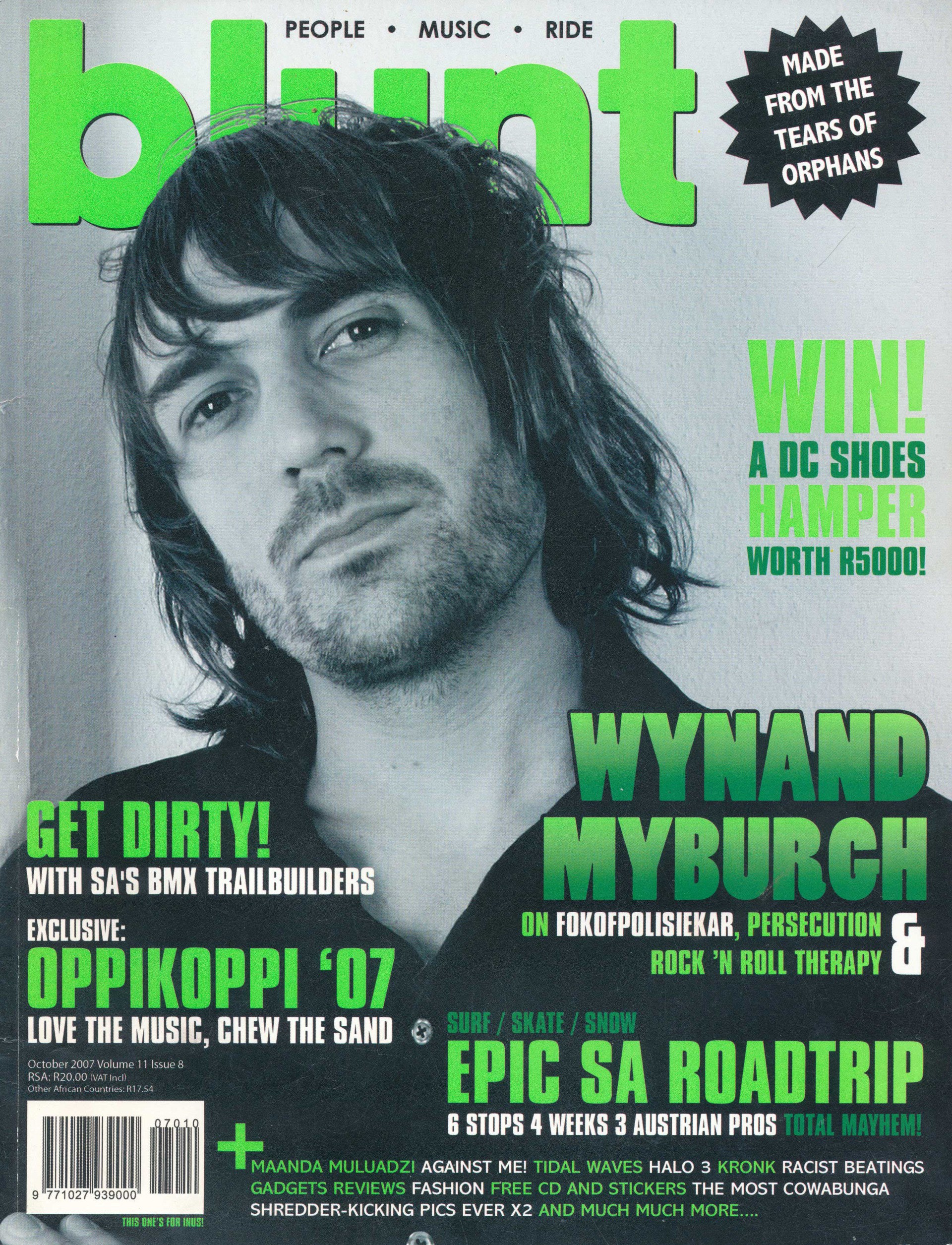

When the first issue of Blunt was born, July 1997, it had been precipitated by Mile’s working with legendary surf photographer Lance Slabbert – who himself was stepping into shooting fashion. It was this multi-thematic interest that would foreshadow the vision of Blunt. Skating, in many ways, is a conduit for punk, hip-hop, graffiti, streetwear – gigs, dive bars, the beach, festivals – it’s the physical arm of a much larger entity largely defined by an innate resilience among young people against all manner of the manipulation (subtle and overt) of human beings by a rigid, oppressive society. This was Miles’ “aha!” moment – he wanted to make a magazine that captured all of it; the sounds, the movement, the energy of this attitude; for himself and his own lived experience growing up skating in Hout Bay, and for those around him too – but particularly so, for the kids who he knew would need the respite skating and its community can offer. In reflecting on the self-expression of subcultural spaces, a clear indicator of Blunt Magazine’s presence in South Africa, and stickers were one such way Miles knew they were on course, “In our first year of launching, we had R2000 available for marketing. That’s it. I spent the entire budget on stickers – and this became a synonymous part of our magazine. Our first year was quite slow, we sold about 4000 copies, and then the second year it blew up to 10000 – and then we became one of the fastest growing magazines in the country, and by the fifth year we were in the top fifty magazines in the country. All the while, I could kind of track this through our stickers – if they were on boards and lamp-posts city to city – but the craziest part was when we went on roadtrips, arrive in small dorpies and find Blunt stickers emblazoned like a coded message, a reminder that the thread we were putting out was really running through the country.” Miles expresses a deeply emotive recall of this – telling me that the magazine was exactly for those kids without access, of all races and backgrounds. In Cape Town, Durban and Joburg the culture and scene was alive and well with events, gigs and comps growing steadily, where people could gather and connect – but further out, in the many parts of our country home to small towns, skating was still a reprieve from that isolation that often is often the drawcard for those who find the sport.

Recent Comments