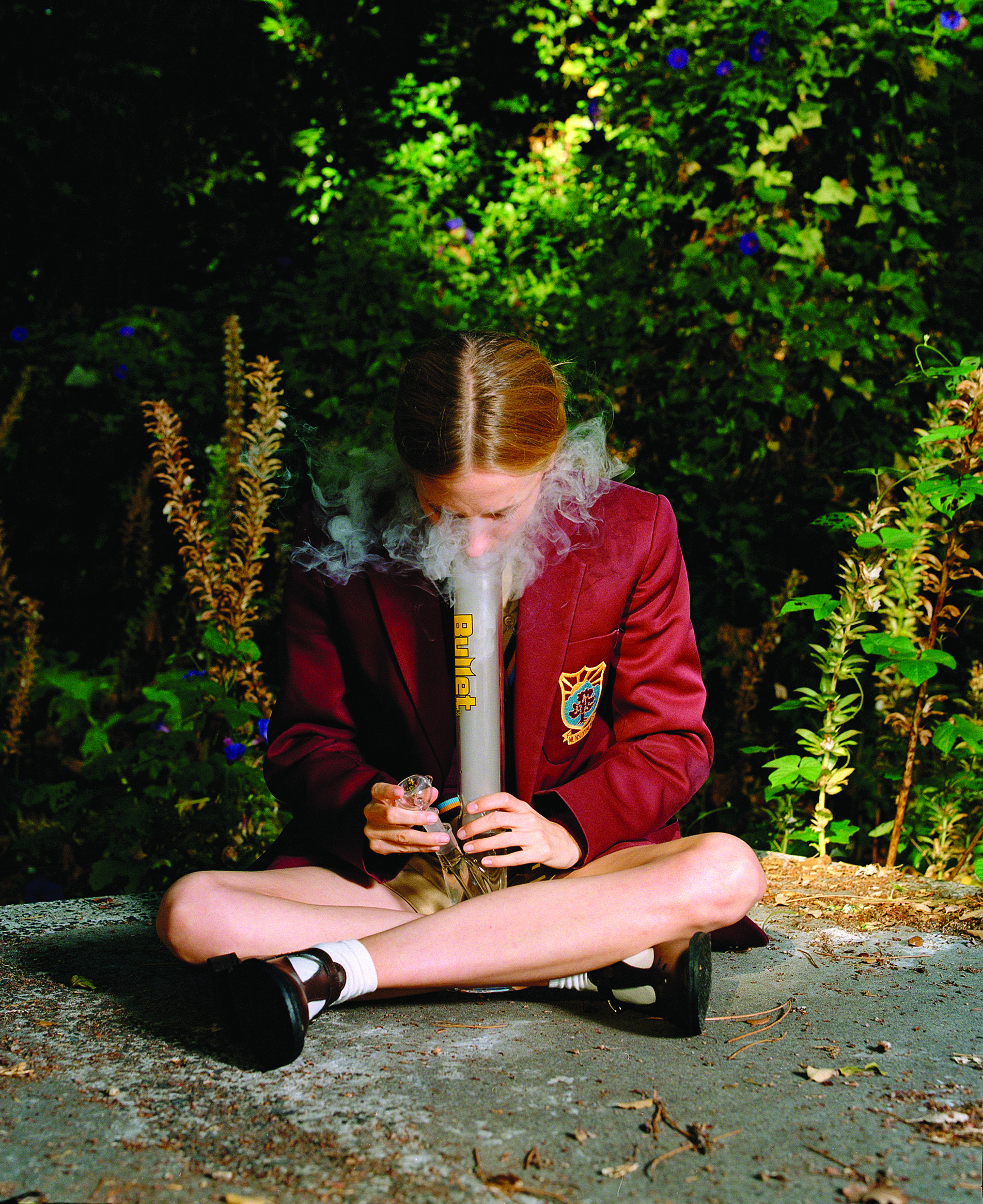

Design Week South Africa returns to Joburg on 9-12 October 2025

Design Week South Africa is an expansive city-wide series of events and immersive experiences that showcase the future of South African design through knowledge-share, inclusivity and support.

Launched in 2024 with more than 90 activations, discussions, showcases, workshops and exhibitions across Johannesburg and Cape Town, Design Week South Africa aims to be the country’s leading design platform. This year, from 9 – 12 October, Johannesburg will come alive as Design Week South Africa 2025 returns, spotlighting the city’s creativity, innovation and bold design thinking.

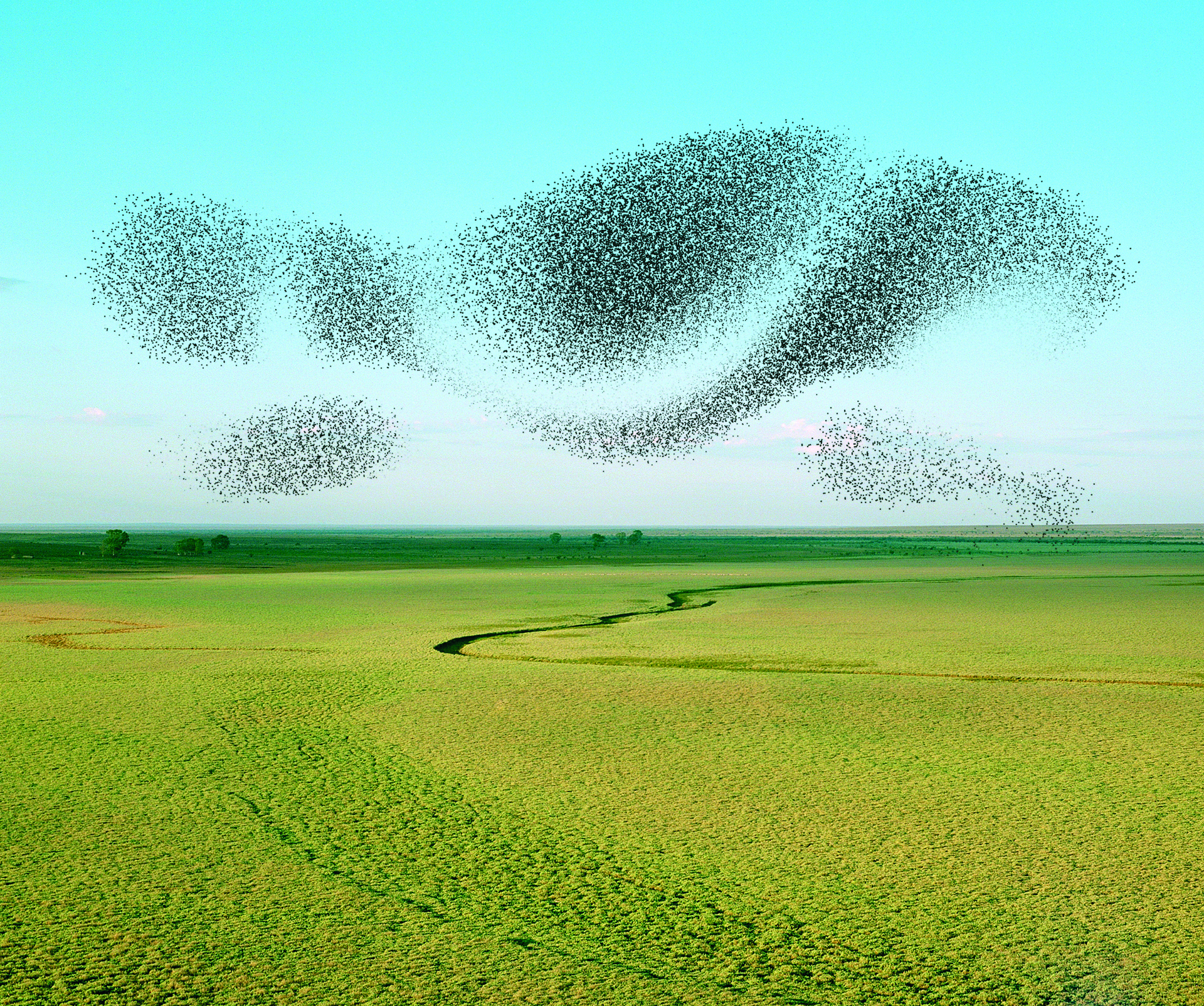

For its second edition, the four-day programme introduces Morning Sessions, a new format that brings dialogue out of a formal stage and into the city’s cafes. Each morning, from Thursday to Sunday (9:00 – 10:30am), leading creatives will share the ideas, challenges and inspirations driving their practice over coffee in intimate, relaxed gatherings — no slides, no presentations, just insight, curiosity and connection.

Curator of Morning Sessions, Simone Schultz shares, ‘With our inaugural Morning Sessions programme, we hope to encourage design discourse at its most human. We believe that the future of South African design won’t be decided only in boardrooms or established institutions, but in these moments of generous exchange between creative practitioners and an engaged, culturally conscious audience.’

All imagery courtesy of Design Week South Africa

Keyes Art Mile, Victoria Yards and 44 Stanley, three of Johannesburg’s most dynamic cultural precincts, will host an immersive programme of exhibitions, talks and pop-ups showcasing the breadth and diversity of African design.

Highlights in the Milpark complex include Africa Textile Talks at The Bioscope and The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember, curated by Tandekile Mkize and presented by Twyg in partnership with The V&A Watershed, alongside an Ivorian jewellery pop-up at Yä-de, innovative lighting conversations at Wat Wat and The Story of Sari for Change installation, which reimagines heritage textiles into one-of-a-kind garments while celebrating the empowerment of women artisans.

In Rosebank, 223 Creative Hub will host a tufting workshop by Fybre Studios, while Keyes Art Mile has partnered with Blaque Inq Contemporaries for an exciting exhibition and artist walkabout, by visual artist Lehlogonolo Masoabi.

Victoria Yards will see a sustainable garden design workshop by Plenty Green Africa, a pop up by streetwear brand FRNDLY SA — with an exciting t-shirt collaboration with Design Week South Africa — and a multi-disciplinary exhibition, Price of Gold, by seven artists and four designers, including Jack Markovitz, Klein Muis and Francesco Mbele. Centred around an imagined future for the city of Johannesburg, the exhibition will also host talks from the artists and designers involved.

Across the road, at Nando’s Central Kitchen, Jozi My Jozi will be revealing their latest creative campaign, Babize Bonke – meaning ‘call everyone’. Featuring extraordinary local champions who are shaping Johannesburg from the ground up, the exhibition will be accompanied by a series of talks.

Around the rest of the city, workshops, studio open days and immersive experiences offer a deeper dive into the city’s design scene, while Soho House will host a curated salon in partnership with Perfect Hideaways. Visitors can also explore a hard-hat tour of a soon-to-open lifestyle development, intimate listening-room experiences, film screenings and Garden Day celebrations, among other surprises.

All imagery courtesy of Design Week South Africa

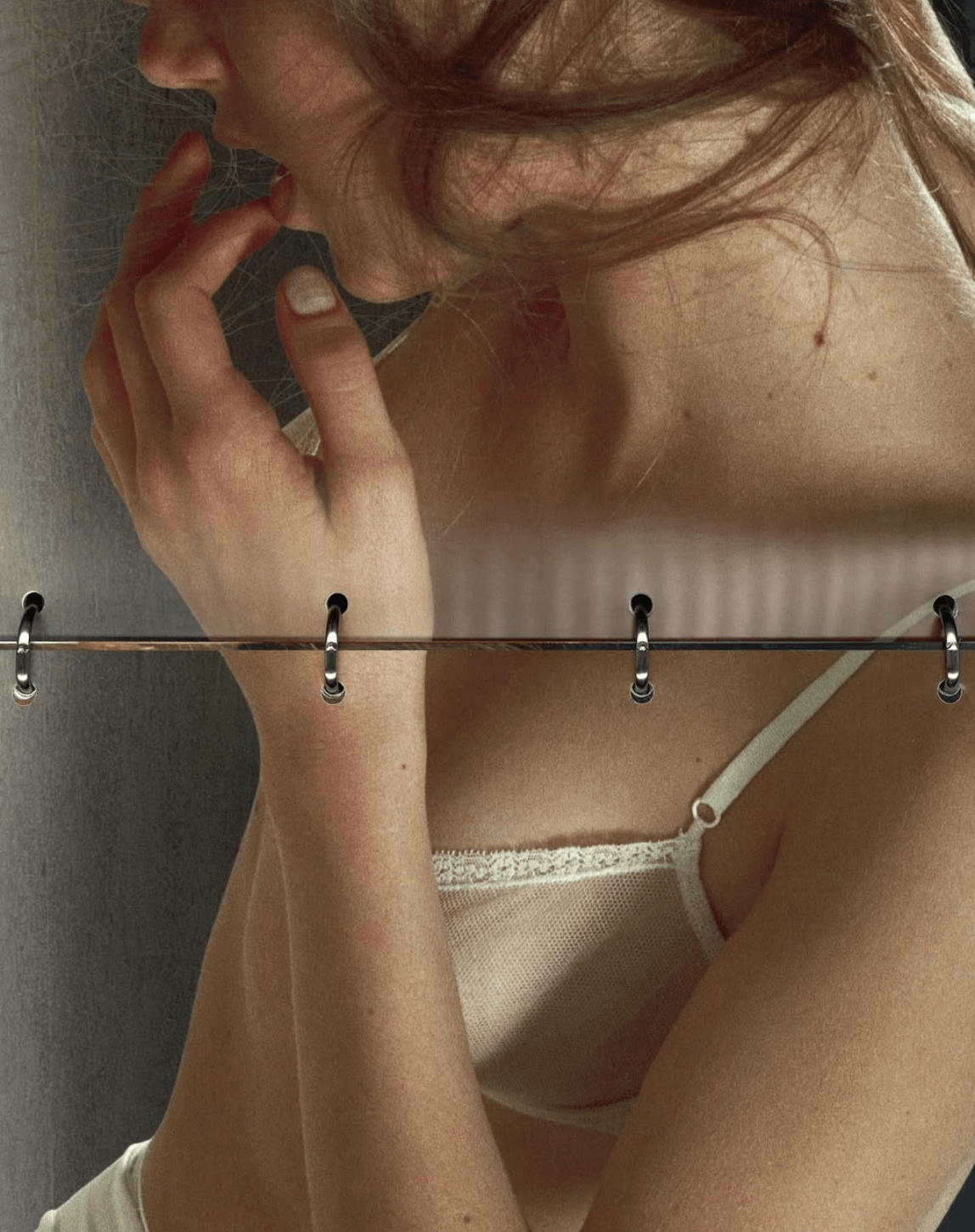

Meanwhile, in Soweto, Creative20 will launch The Annual Kasiology Festival in collaboration with Jozi My Jozi, marking a township-based celebration of design, creativity and lifestyle that coincides with the upcoming G20 Summit in South Africa.

“Both 44 Stanley and Keyes Art Mile embody the spirit of independent creativity and African innovation, making them natural partners for Design Week South Africa,” says Margot Molyneux, founder of Design Week South Africa. “We are thrilled to present activations that reflect the depth, diversity and energy of the continent’s design community — and to invite the world to see how South Africa’s designers are shaping the future.”

ABOUT THE TEAM :

Design Week South Africa 2025 is curated by South Africans passionate about this country’s design sectors, the creative economy and growing pride and acknowledgement of South African and, more broadly African, design. The core team comprises Margot Molyneux, Zanele Kumalo, Roland Postma and Simone Schultz, while a broader advisory team, including local and international industry leaders, has also been formed, with members announced later this month.

More about the core team:

Having spent 10 years building her namesake clothing studio, Margot Molyneux, a manufacturer and retailer of boutique collections of men’s and womenswear, Margot more recently turned her attention to the world of media, specifically focusing on interiors, architecture and decor, fulfilling the role of Managing Editor of House and Leisure publication and General Manager at independent publisher LOOKBOOK Studio. 2024 brought the launch of, Design Week South Africa, a seemingly natural career transition as she combined her love of design and storytelling with her enthusiasm for the local creative industry and its growth and development.

Since joining the biggest Sunday newspaper and working in various roles at the top lifestyle publications in the country, Zanele Kumalo continues to partner with premium brands to create and lead communities built around the creative economy – art, culture and design. With a twenty-year career in media, marketing and communications that sees her growing the now six-year-old boutique content studio whatzandidnext, she works as the Johannesburg liaison for Soho House Cities Without Houses, a global members club; the founding director of kumalo | turpin, a newly launched contemporary art space in Johannesburg; and on other projects.

Roland Postma believes that building people-first cities is a necessity, not an idealistic goal. With a first class Honours in Urban and Regional Planning from RMIT in Melbourne, he is currently the Managing Director at Young Urbanists NPC, where he aims to inspire a new generation of thinkers and doers around city design and management. Through co-founding the Active Mobility Forum and the public-private partnership Safe Passage Programme with the SDI Trust, he wants to prove that change is possible by providing solutions to local governments around the areas of housing, urban design and transportation.

Following on from her position as editor-in-chief of Asia’s leading design publication, Design Anthology, Simone Schultz brings an international perspective and understanding of the global creative landscape and its evolving narratives. She has spent a decade working with stakeholders in Asia Pacific, Europe, Africa and beyond at the intersection of design and media, helping designers, architects, thought-leaders and brands communicate their stories across mediums, geographies and contexts. Her involvement in Design Week South Africa marks her renewed focus on her home continent, where she will draw on her global experience to help build a window into and a bridge between Africa and the rest of the world.

Visit Design Week South Africa’s Website here

Follow @designweeksouthafrica on Instagram

The Design Week South Africa brand identity was created by Hoick @hoick.

Poster illustration by Koos Groenewald @kooooooos.

Press release courtesy of Design Week South Africa

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za

Recent Comments