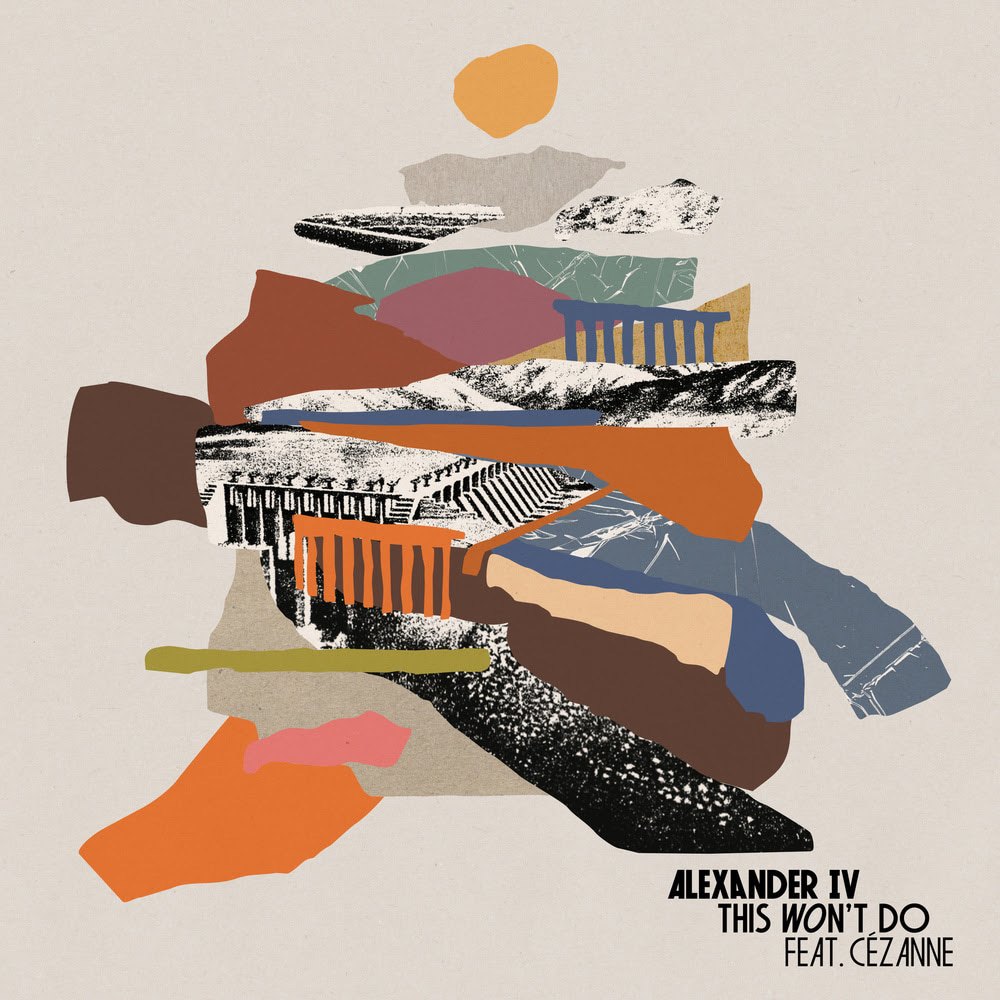

Alexander IV releases ‘This Won’t Do’ feat. Cezanne

Sonar Kollektiv proudly presents “This Won’t Do”, the new single from producer and multi-instrumentalist Alexander IV. Featuring the captivating vocals of Cézanne, the track marks the first release from Alexander IV’s debut album ‘Alchemist’, due in March 2026.

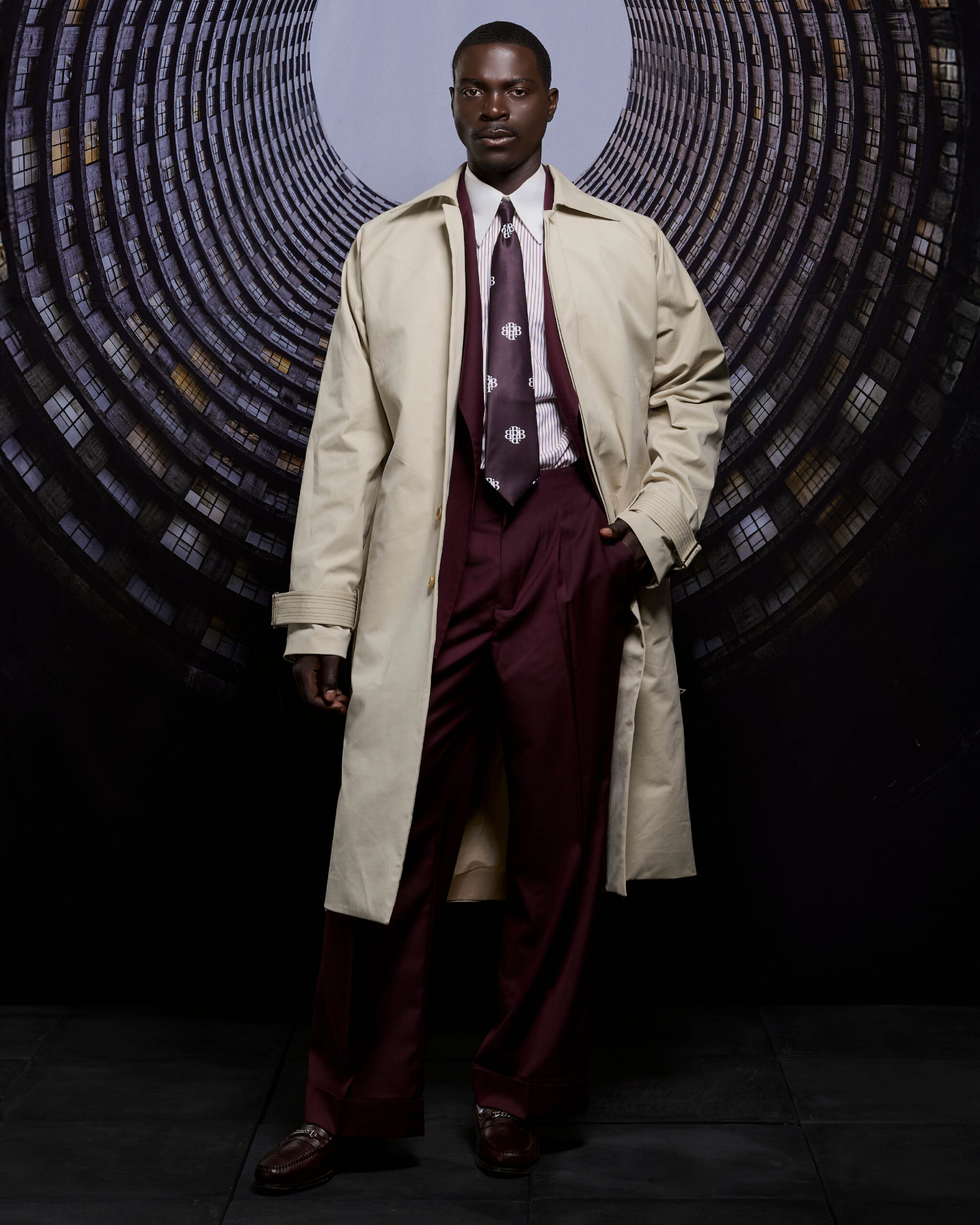

Alexander IV is the pseudonym of eclectic Dutch producer, multi-instrumentalist, and eminent beat-maker Joris Feiertag. While widely known for his club-focused output under the name Feiertag and as the drummer for Dutch funk outfit Kraak & Smaak, this now well-worn sobriquet has allowed him to explore his hip-hop, soul, and jazz roots with freedom and depth. As Alexander IV, he crafts music that feels brand-new yet nostalgic, uncomplicated yet masterful.

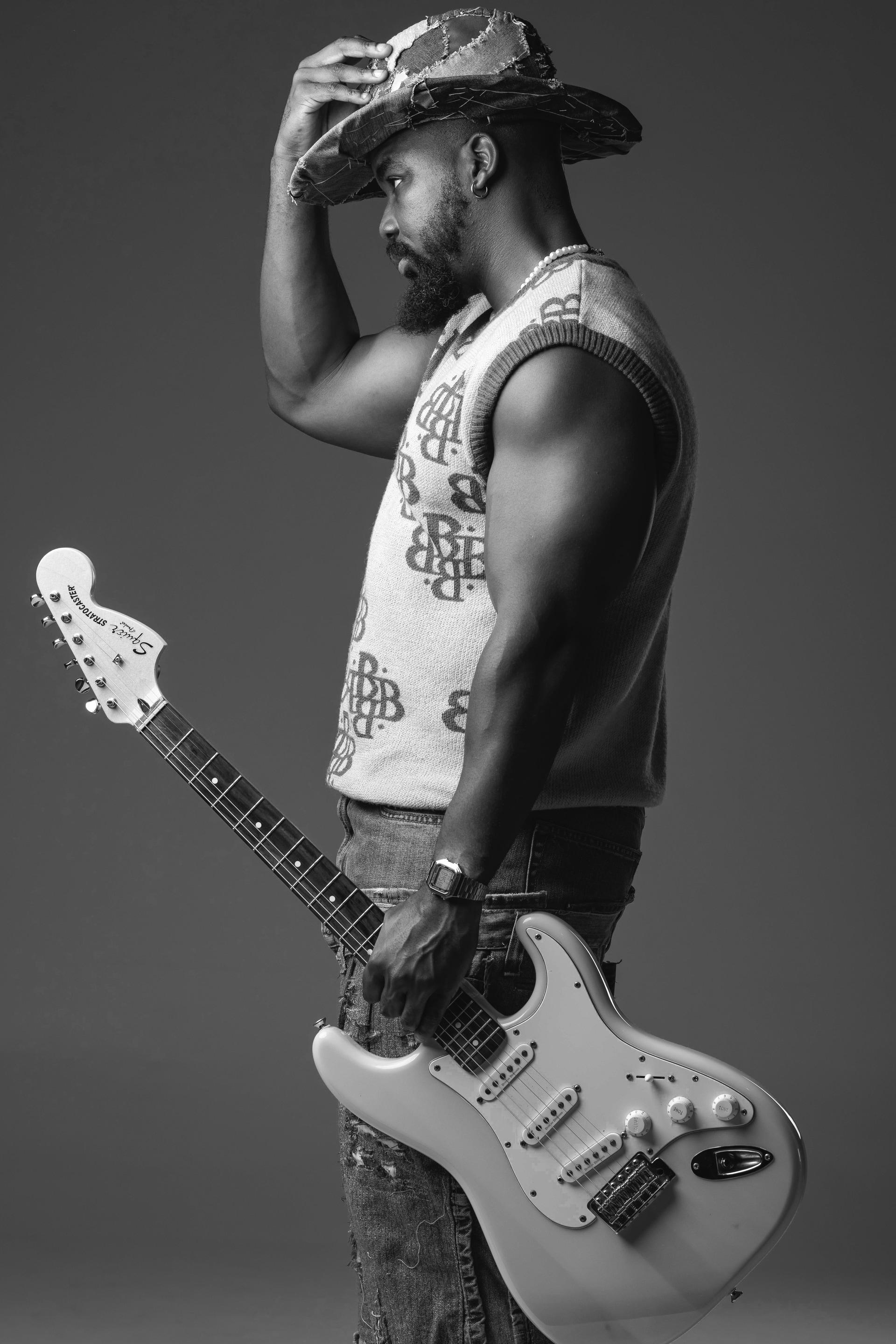

“This Won’t Do” is a serene slice of modern soul that, despite its choppy jazz-fuelled 116 bpm breakbeat, glides effortlessly with a cinematic warmth. The track sees Alexander IV paired symbiotically with fellow Dutch artist Cézanne, whose distinctive voice also featured on his earlier release “Burnin’” from the Bloom EP (via Sidekick Music). Here, Cézanne delivers a heartfelt vocal that floats perfectly above layered keys, a subtle but infectious groove, and fine-tuned rhythmic detail.

The single is also a first glimpse into Alchemist, a deeply personal record built from small sonic fragments—chopped, reversed, slowed down, and reimagined. “The cinematic atmosphere I envisioned came through just as I hoped,” Joris explains. “One of the things I’m most proud of is the detail. Every element has its place. Even the smallest quotes and samples are intentional—everything aligns.” The album is a nostalgic journey through sound, informed by formative influences such as Mr. Scruff, Thievery Corporation, The Herbaliser, Tosca, and Kruder & Dorfmeister, as well as modern luminaries like SAULT and Khruangbin.

Throughout the project, Feiertag worked closely with a cast of gifted musicians—Bart Wirtz (flute and saxophone), Luuk Hof and Samir Saif (trumpet), and Robin de Zeeuw (double bass)—weaving their contributions into a rich sonic tapestry grounded in jazz and soul.

“Vocals throughout the album come from Cézanne, Oli Hannaford, and Pete Josef, ” he adds. “It was a joy to work with all of them—especially on tracks that lean more toward structured songs, some of which were influenced by afrobeat and artists like SAULT. ”

As the album title suggests, Alexander IV has taken these elements—analog and digital, past and present—and transformed them into something pure and intentional. With “This Won’t Do” , he opens the Alchemist chapter in style: subtle, soulful, and full of promise.

Listen to ‘This Won’t Do feat. Cezanne’ here

Press release courtesy of Only Good Stuff

Recent Comments