Colouring The Lines Of Sound: A Look Into The Sonic Universe Of Blue Lab Beats

I’ve always wondered what the heart and soul of music are. Is it the beat or the lyrics? In a brief conversation between my lifecoach and I, where we spoke about the healing quality of musical frequencies, I realised there is something ethereal about instrumentation and how it forms the soul of any song. Having spent some time creating beautiful projects and songs with my mates, I have developed a sincere appreciation for the value of producers and sound engineers for the unsung work they put into curating the essence of the soundtracks in our lives. Coming from a rich lineage of musical behemoths, when I was introduced to Blue Lab Beats, I was whisked away into the detail that my father appreciates about musical structure and form and naturally, I couldn’t resist introducing him to the BLB experience.

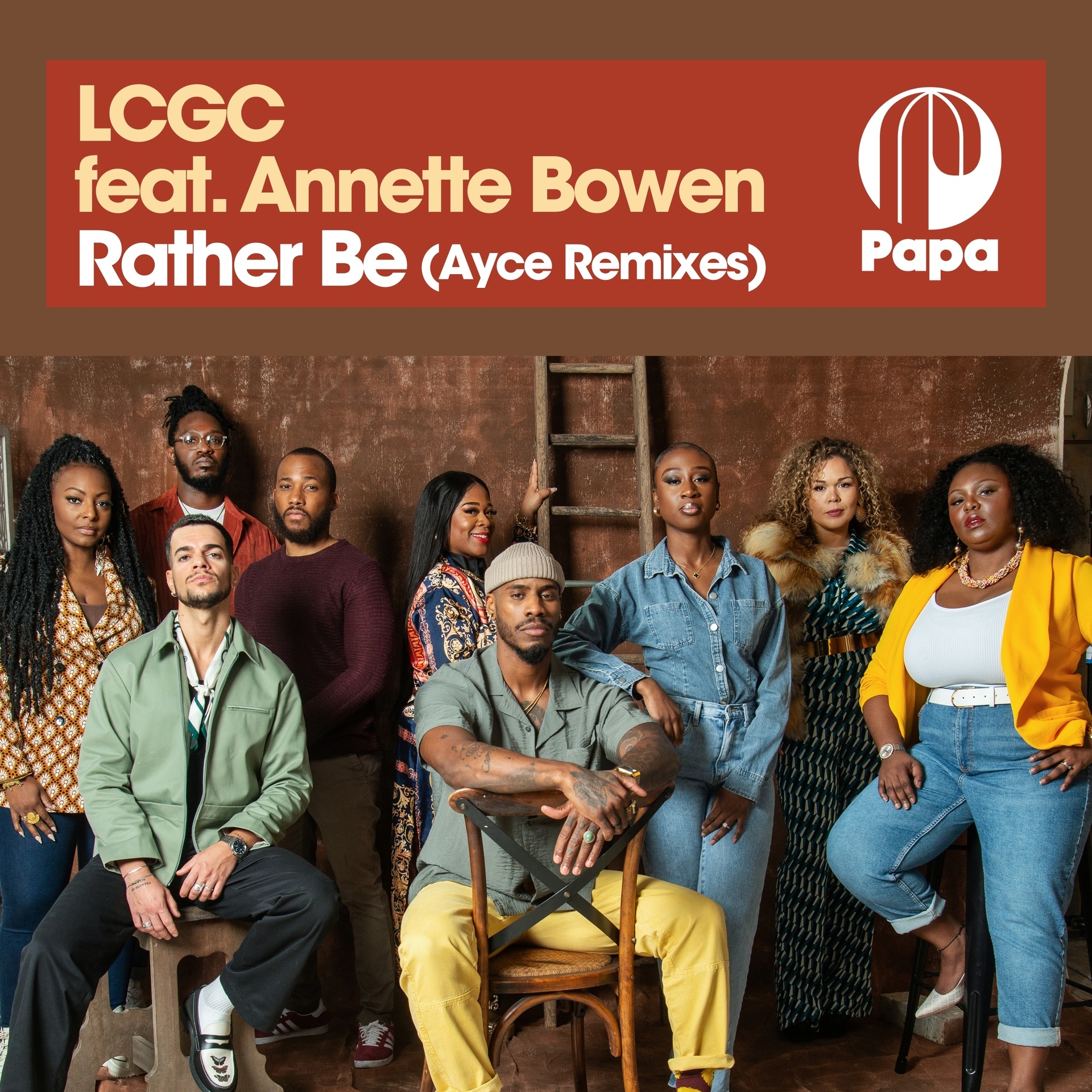

Consisting of NK-OK and Mr DM, Blue Lab Beats are multigenerational talents from the United Kingdom who cater to the African diaspora while staying true to their London roots. They achieve this through a seamless blend of production and multi-instrumentation coupled with the unwavering power of collaboration, soothing our listening senses with a fusion of Jazz, Hip-hop, Afrobeats, Soul and Electronica born from organic all-night jam sessions in warehouses around London. Inspired by their contemporaries ranging from J.Dilla, 9th Wonder, Missy Elliot and the collaborative prowess of Knxwledge and Anderson .Paak, Blue Lab Beats have pushed the needle from being bedroom producers remixing tracks from A-listers such as Dua Lipa and Rag’N’Bone Man to being Jazz FM innovation and Grammy award winners for their production on Angelique Kidjo’s “Mother Nature.”

Image Credit: Dalong Ye-Lee

Image Credit: Dalong Ye-Lee

Their masterful discography boasts notable projects such as “Blue Skies EP,” “Xover,” “Motherland Journey,” and “Blue Eclipse“, which features my favourite song, “Cherry Blossom,” the sonic textures from each offering are a voyage unto itself, a listening experience with purpose garnering them over 50 million collective streams. Whether it’s your time for reflective meditation, a road trip, a romantic two-step and a light salsa with your lover, or downtime from a long day at work, there is a Blue Lab Beats vibe for every moment of life. The sheer diversity of the Blue Lab Beats catalogue masterfully translates into the stage with clinical precision, resulting in them touring the world performing in countries like Poland, Holland, Netherlands, Turkey, Czech Republic, and South Africa, providing out-of-body experiences at each turn.

Curious to understand the genius behind the pulse, I experienced an indulging conversation with Blue Lab Beats about their origin story, the state of production culture, their creative process, the art of sampling and more.

Some say it takes 10,000 hours to become an overnight success, and I’d like to start our conversation there. Please tell me more about who you are and take me through your upbringing and journey into the discovery and perfection of instrumental music?

BLB: “Many people probably discovered us two years ago after the release of ‘Motherland Journey‘ and our Grammy win with Angelique Kidjo. But we’ve actually been producing together for 12 years. We first met at Weekend Arts College, an amazing youth centre providing affordable access to live music, music production, singing, dancing, and acting. It’s a great alternative to expensive one-on-one music lessons, which can be really costly here.

The establishment has been around for about 45 years, and one of the key figures running it was Celia Greenwood – she’s a total boss. She’s helped multiple generations of great musicians come through there, including Steve Williamson, Jason Rubello, Alex Garner, and Miss Dynamite. Even in the younger generations, you’ve got people like actor Daniel Kaluuya, who’s doing well. Just a whole host of massive talent has emerged from this place.

So we met there 12 years ago and have been producing together ever since. We just released our fourth album this year, and we’re already working on our fifth.”

Image Credit: Dalong Ye-Lee

Image Credit: Dalong Ye-Lee

In an era where we tend to get microwaved beats that appease the algorithm, you put care, creative direction and effort into your beats. What are your thoughts about the current state of production culture? Are we making progress or regressing the quality of instrumentation?

BLB: “We think it’s a bit of both, honestly. We love what beatmakers have been doing recently, especially with SoundCloud slowly making a comeback these past couple of months. Since getting back into DJing, we’re always looking for loads of edits. It was a game-changer when SoundCloud removed that advertising restriction, which made everyone stop using it.

When it comes to beat makers, we’ve noticed there’s definitely been a trend of people grabbing samples from Splice or royalty-free packs. But to really finish a song, you need musicians to add different elements. Being able to go to a different section with different chords – that’s such a beautiful thing. It’s crucial to maintain that musicality.

The bottom line for us is keeping things organic. In today’s convoluted music world, sticking to an organic approach is refreshing and well-received by audiences and sonic fans. Speaking as musicians, it’s easy to distinguish when that organic approach hasn’t been taken – you can tell when an artist has veered away from that authentic sound.

One thing I noticed in your discography from “Blue Skies” to “Blue Eclipse” and beyond is the rich presence of instrumentation and meticulous arrangement in your compositions. How do you approach structuring the compositions and arrangements in the creative process of your songs and album sequencing?

BLB: “One significant way we approach our creative process starts with NK laying down the drums. He plays them freehand without quantization – quantizing would remove the organic feel. Once a full percussive structure is in place, we prepare the keyboard, lay down a bassline, and start fleshing out ideas that complement those drums.

From there, we work together to develop the track. As needed, we can adjust the chords and modify the harmonic and melodic structure. It’s a building process: we start with the drums as our foundation, add the bass, and then layer in the harmony and keys. That becomes our framework from which to build everything else.”

What I love about sampling is the power of recreation, taking something basic (or extraordinary) and giving it a new context of expression. What is your relationship and approach to sampling in your music?

BLB: “Sometimes in our creative process at Blue Lab, we’ll start with a sample idea. We’ll come to David with a basic song concept based on a sample, but since we don’t want any legal issues, he replays everything. We then structure the song to be harmonically similar to the original inspiration. ‘Pineapple’ is an excellent example of this approach – many people think we sampled it, but we replayed every detail ourselves.

Regarding resampling, we believe the best approach is to research videos from the era you’re drawing from. Look up studio footage, if it exists, and study how they’re using the mixing board. If you want to learn about reverb or echoes, study the dub legends – they were incredibly ahead of their time with their mixing techniques. The same goes for conscious reggae legends and the Motown crew.

Once you learn these techniques, your replayed parts start sounding like authentic samples. Then you can feed that back into your drum machine, and you’ve created something completely original while capturing that classic feel – all done yourself.”

Watch ‘Pineapple’:

You have experienced what is to be signed to labels like Blue Note and are now independent. Regarding the business side of music, which do you feel is the better fit for creatives such as yourselves and why?

BLB: “Blue Note was amazing from the beginning days, especially when they flew us to Ghana for music videos – that was absolutely insane. They really got our vision. But when you’re creative nowadays, navigating the major label industry can be tricky. Since Blue Note is owned by Universal, even if you’re on a smaller label, the more prominent entities still control the money. Their decisions can feel very random – they’ll have a good or bad day, affecting everything. This has recently intensified with how major record labels manage their artists.

We don’t particularly agree with how they treat their artists and creatives because of this randomness. That’s why we prefer having more control over our work. It’s just better knowing we can post something today and make certain decisions without going through an enormous approval process. We can just check with our management quickly and move forward. It feels more natural having that control over our stuff.”

Watch “Labels (Live at The Royal Albert Hall/2022)’:

Thank you for joining us for this interview. Before you leave, could you tell us more about what you have planned for the future beyond the “Options” single and upcoming international tour dates?

BLB: “We’ve got more music coming for the whole world to hear. We’ll be dropping two EPs from artists signed to our label – Eva Gadd and Farah Audhali. Eva’s EP will drop in November and Farah’s will drop early 2025. We’re really excited about these releases since we produced both projects entirely. We’ve also got some other artists on our label who will release early next year. While we’re not producing those projects directly, we’ll be doing remixes for them. That music will have more of a jazz, psychedelic vibe. We can’t wait for everyone to hear all this new music. And at some point, we’ll start working on our own album five, though we have no idea where we’re going to take that one yet. We’re excited about the future.”

While we can never truly settle the debate of what ranks higher between instrumentation and lyricism as they are equally important, each listening session of Blue Lab Beats reminds me to celebrate the art of curation. When the collaborative spirit calls for a well-rounded musical piece, we achieve the most elusive feat in creativity, timelessness.

Written by: Cedric Dladla

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za

Recent Comments