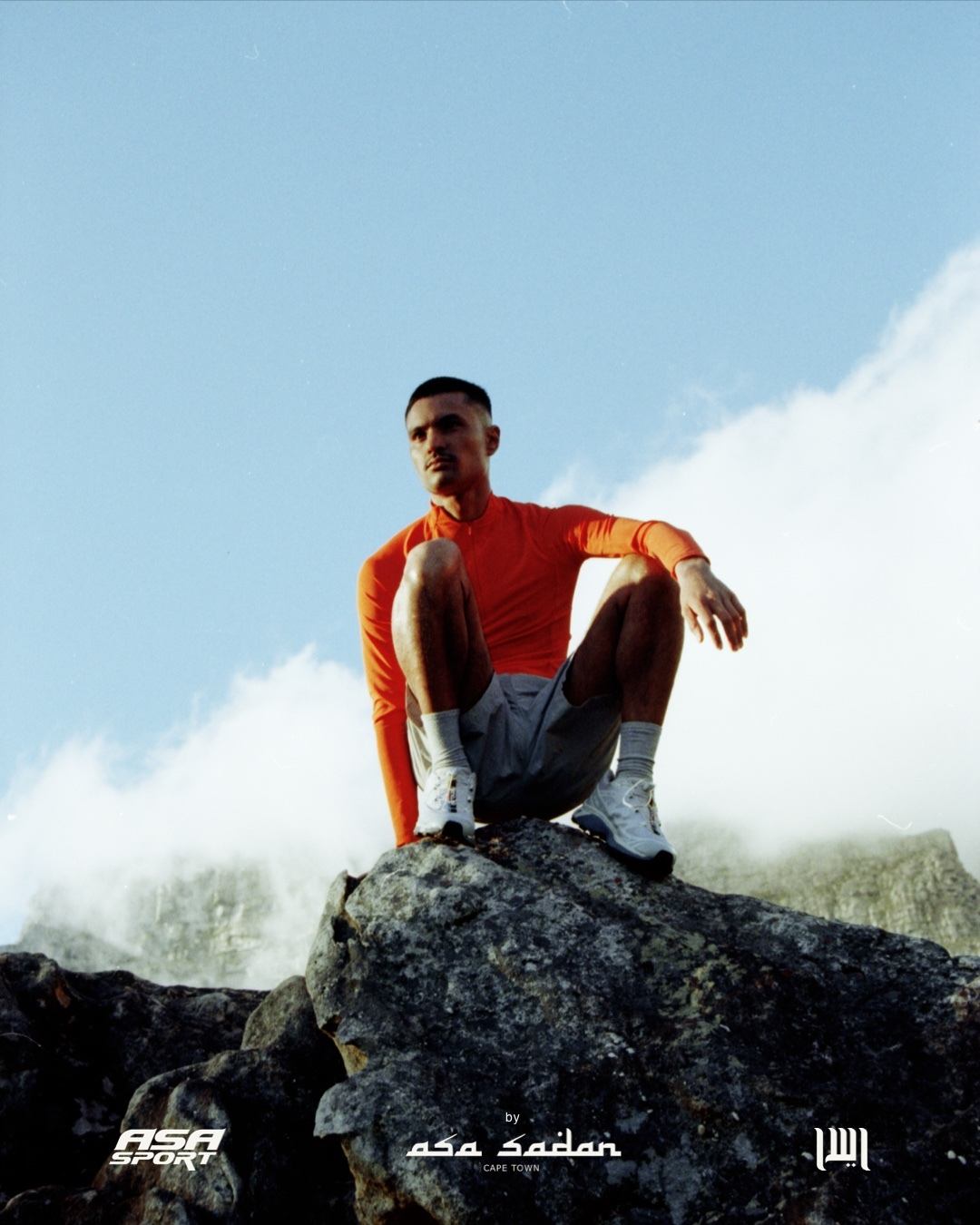

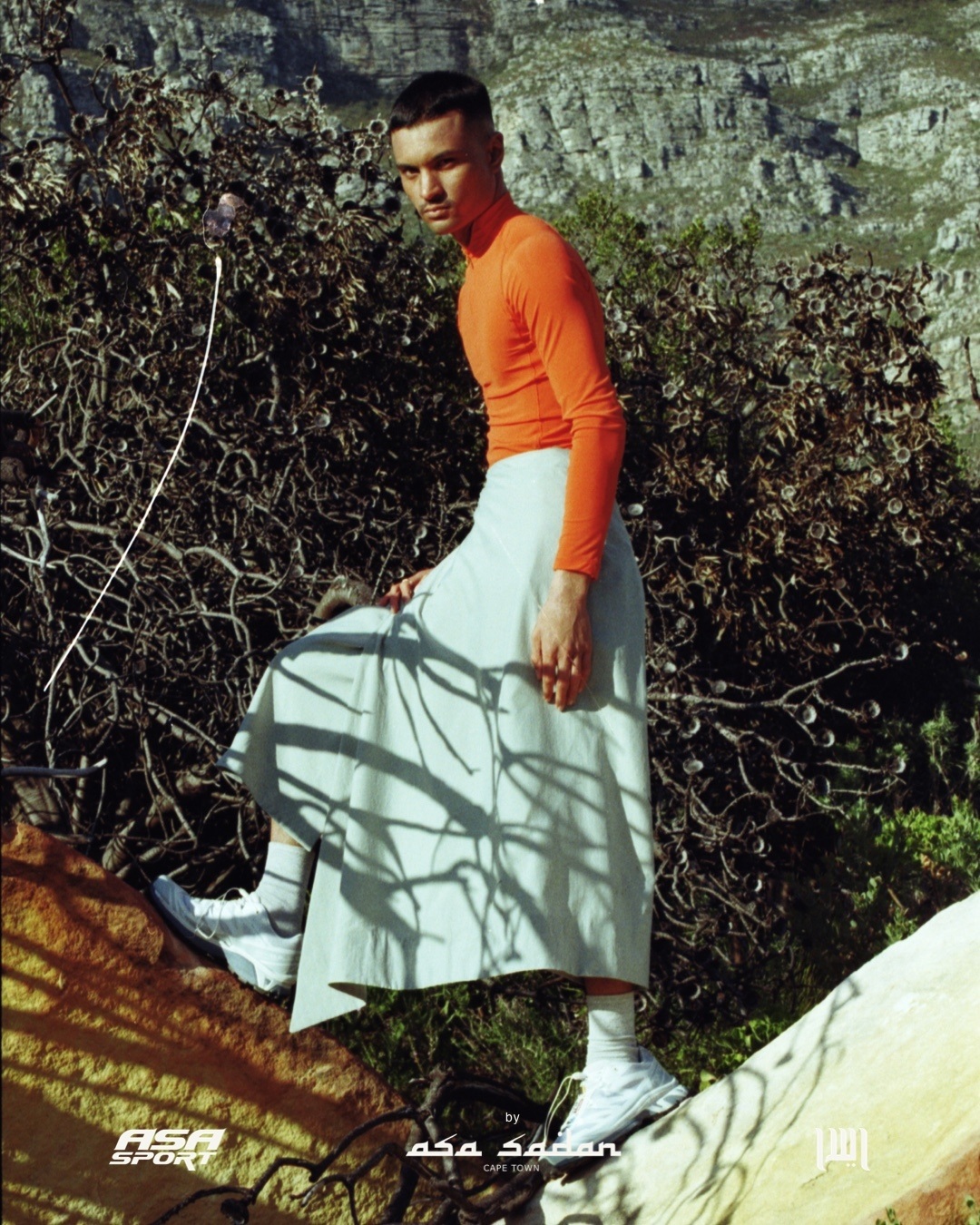

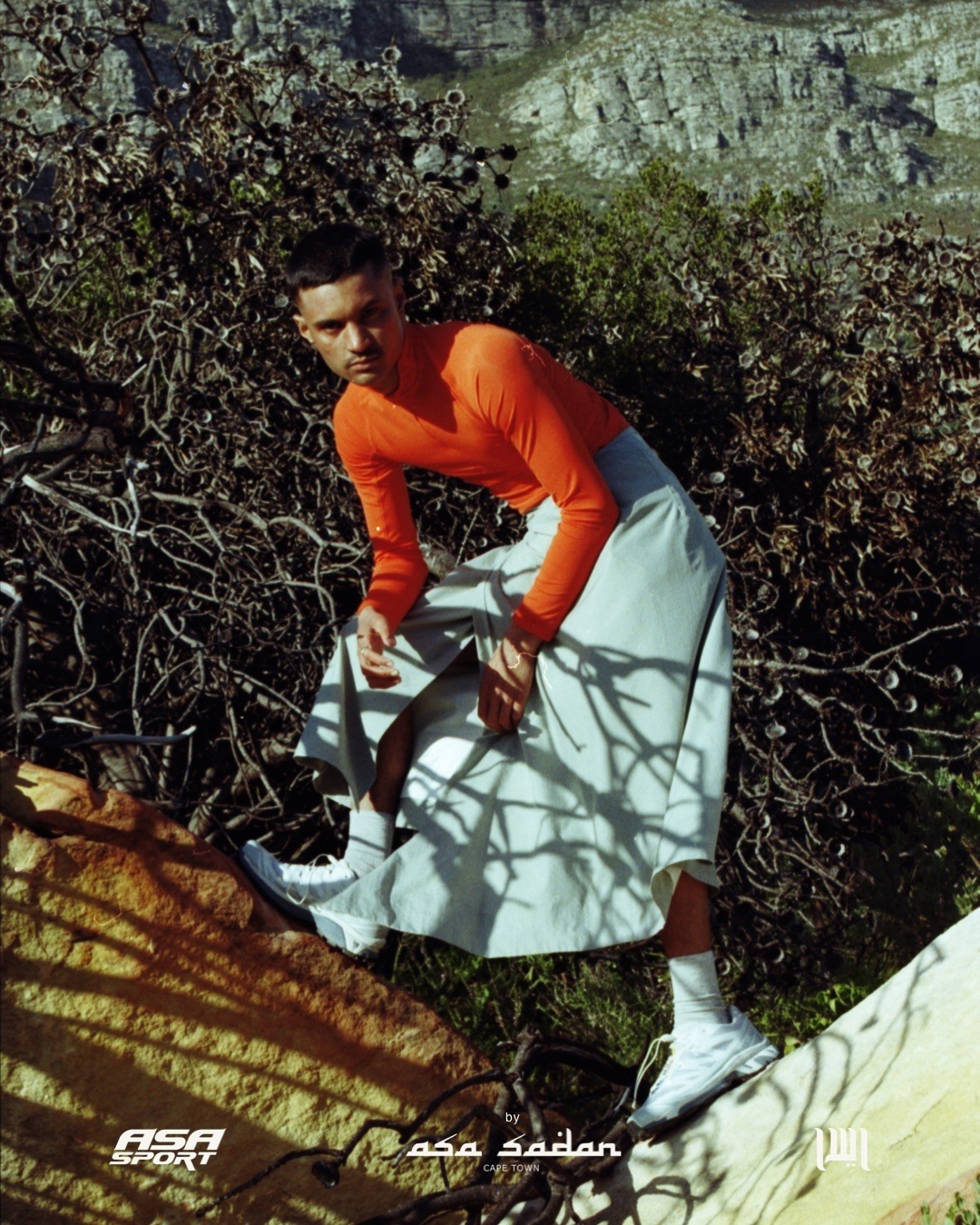

VIVIERS, the South African fashion house, unveils their concept-driven fashion experience at South African Fashion Week (SAFW). With the debut of their SS24 fashion film ‘Re-Trace, Re-Memory, Re-Set, Re-Culture,’ VIVIERS highlights their unwavering commitment to the South African fashion landscape and their larger vision of fostering a homegrown African fashion community and clothing industry.

Having emerged on the SAFW scene through the Fashion Bridges Program in April 2023, VIVIERS returns to SAFW, reinforcing their dedication to the local fashion industry and their aspiration to create a thriving African fashion community. This is not merely a showcase of garments; it’s a statement of purpose.

“Through a collective and creative hybrid space called ‘Hub-of-The-Hand,” VIVIERS collaborate with numerous South African Artisans, using South African raw material like Cape Wools, South African Mohair, Ostrich products, Gold and Diamonds and South African Leather, with the idea to further promote the South African clothing, textile and luxury Industry, as well as preserve South Africa’s heritage of craftsmanship.

“Through visualisation and co-emergence, we aim to contribute and to establish South Africa as an Eco-Hub or destination for Supreme Craftsmanship in Luxury manufacturing; a country that leads with its slow and Conscious approach. Showcasing our collection not only on a global platform such as Milan but also within SAFW in Johannesburg is a pivotal element of our commitment to this initiative” said Lezanne Viviers, the creative director and founder of VIVIERS. “This also give me a unique opportunity to edit and change the styling of my collections to respond to future of these two different platforms, as every iteration opens up the collection to a different audience.”

Indeed, VIVIERS recently presented their artisanal capsule collection SS24 ‘Re-Trace, Re-Memory, Re-Set, Re-Culture’ as part of the official Milan Fashion Week, marking their second live event in a year, following their digital debut in September 2022.

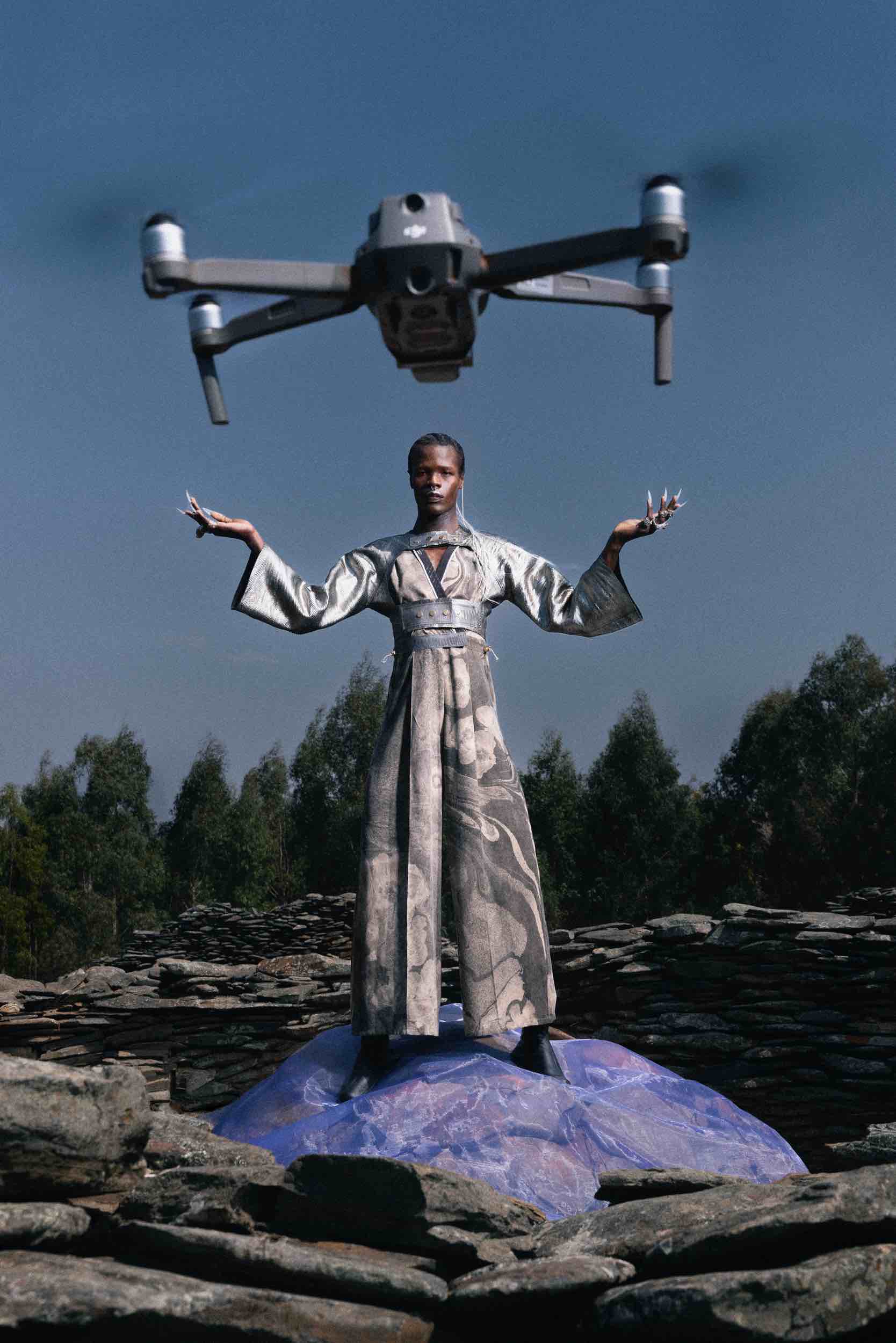

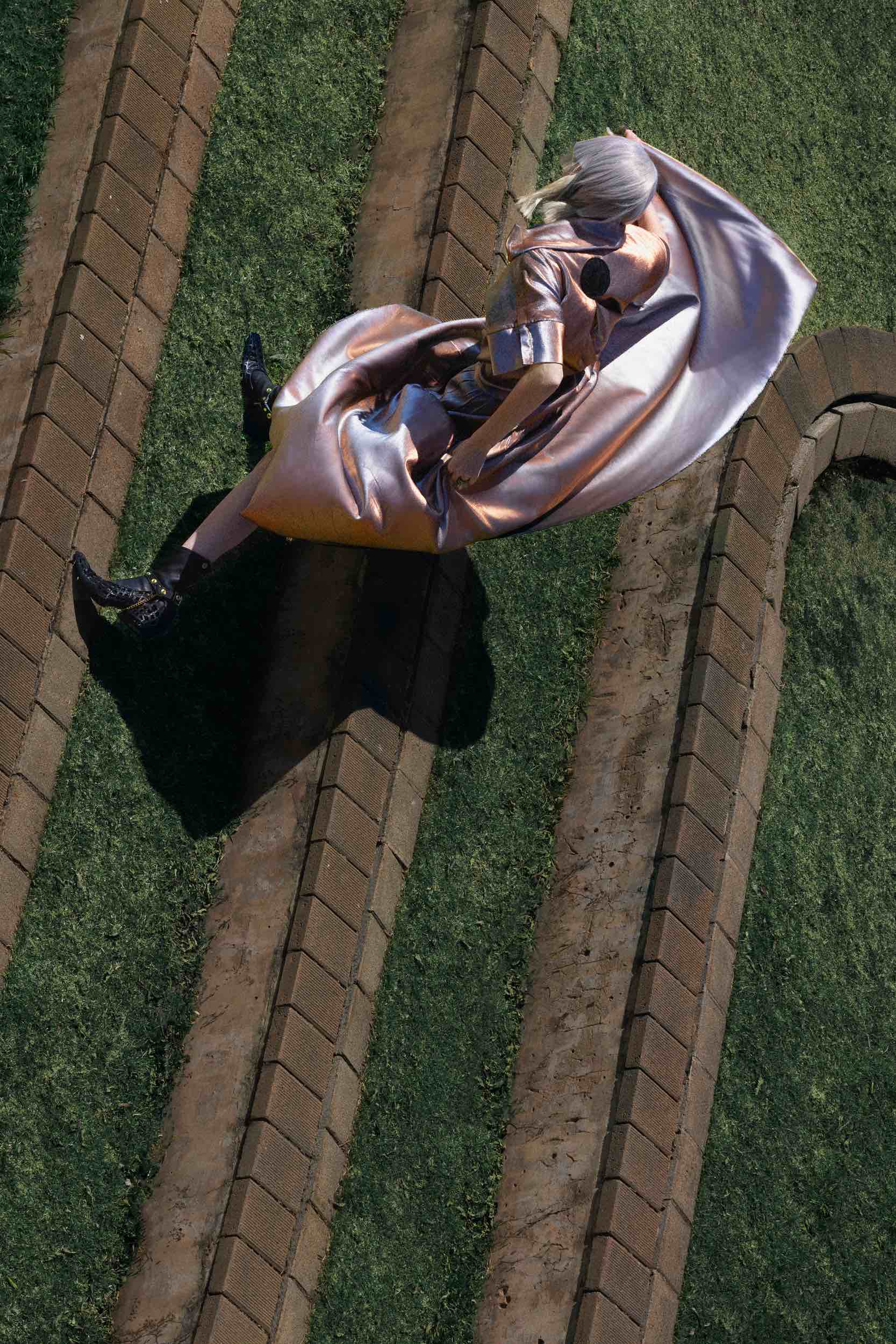

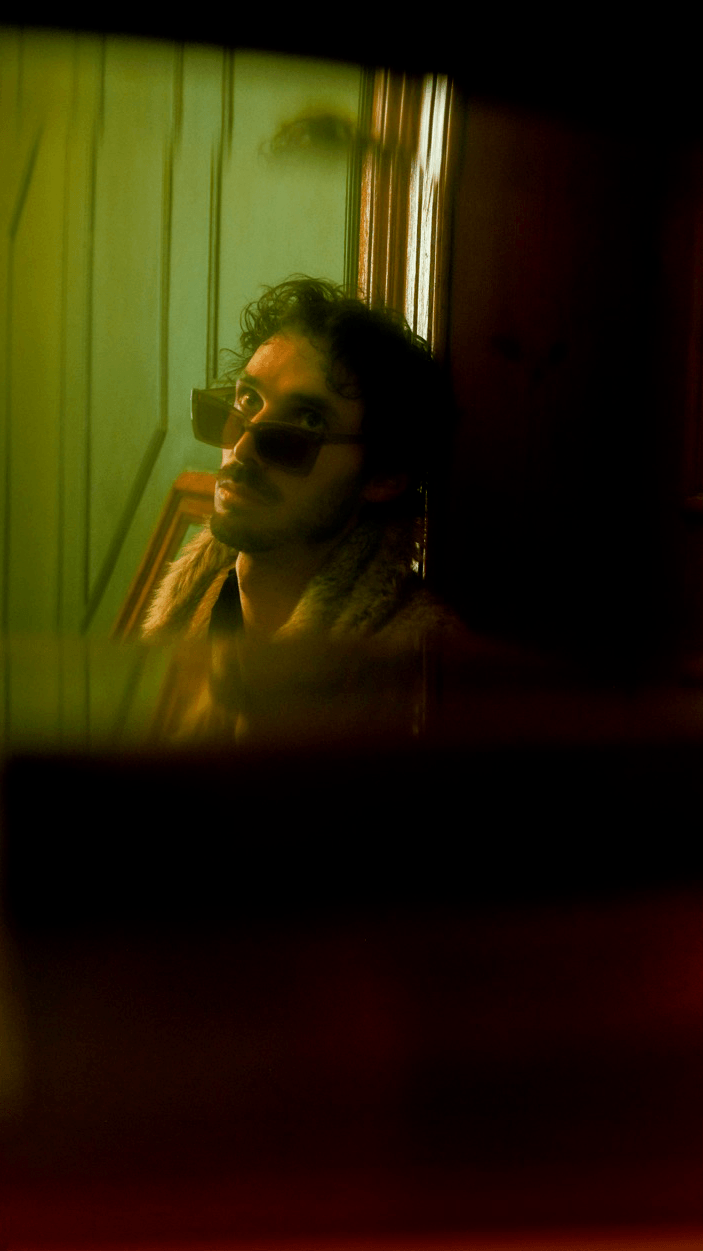

The SS24 fashion film, ‘Re-Trace, Re-Memory, Re-Set, Re-Culture,’ serves as a unique canvas, offering a glimpse into the soul of VIVIERS’ SS24 collection. It’s not just a film; it’s a conceptual statement.

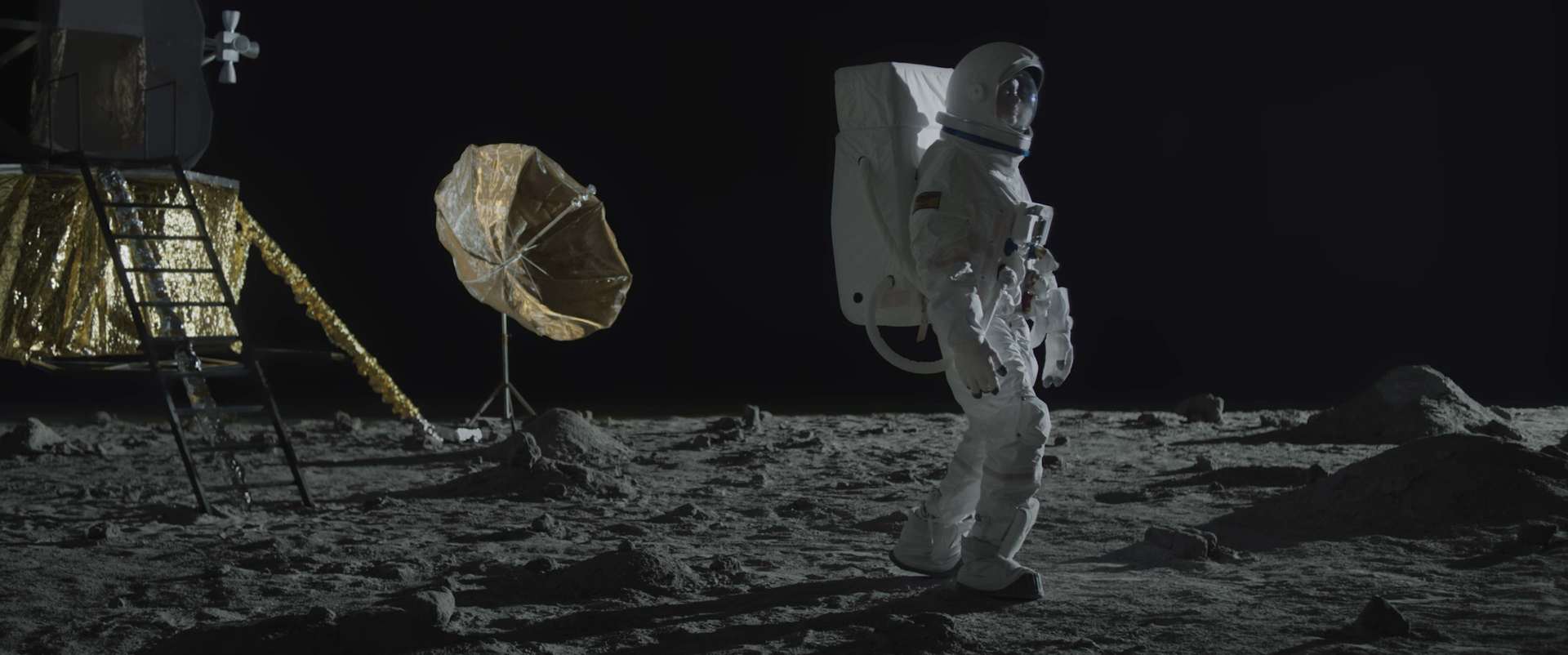

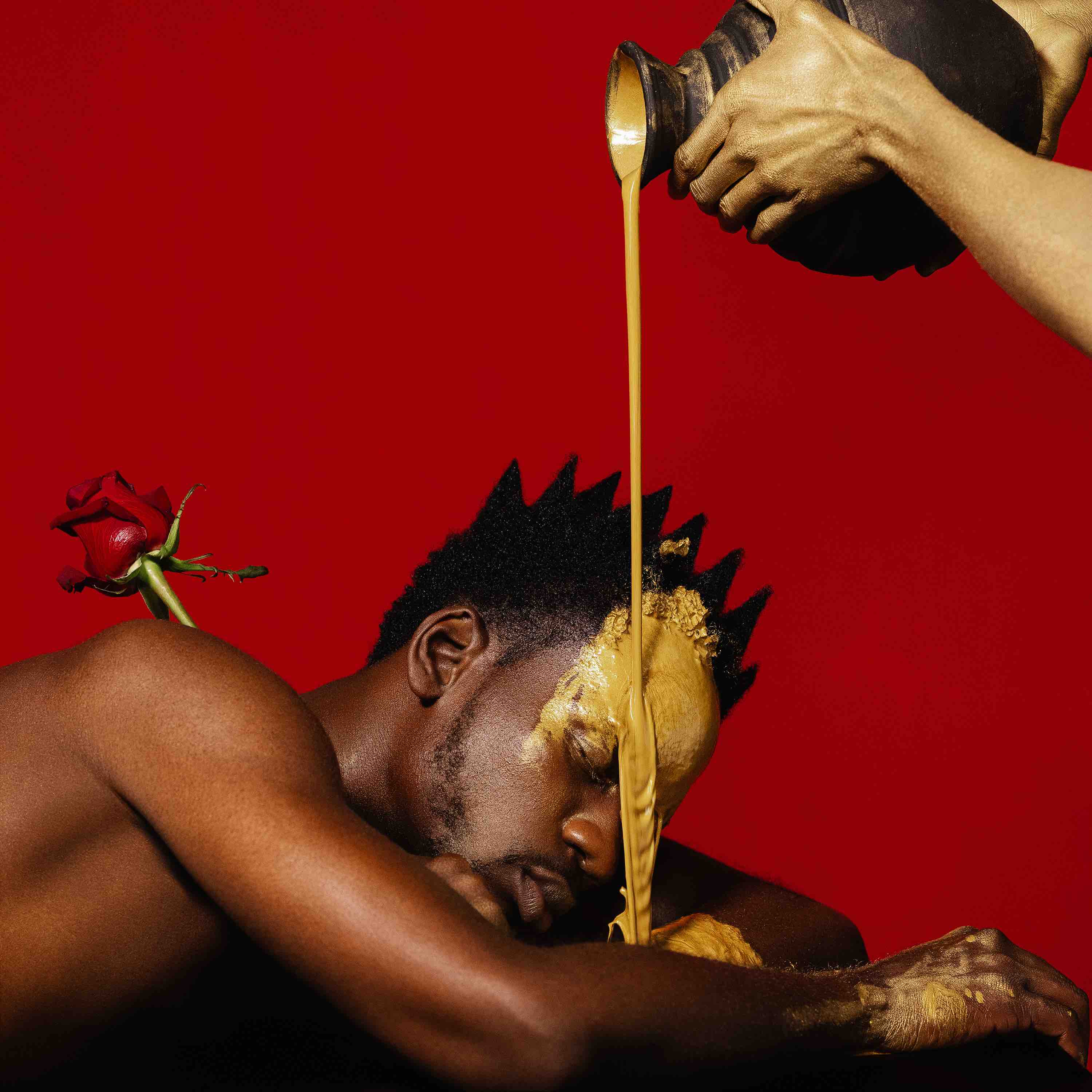

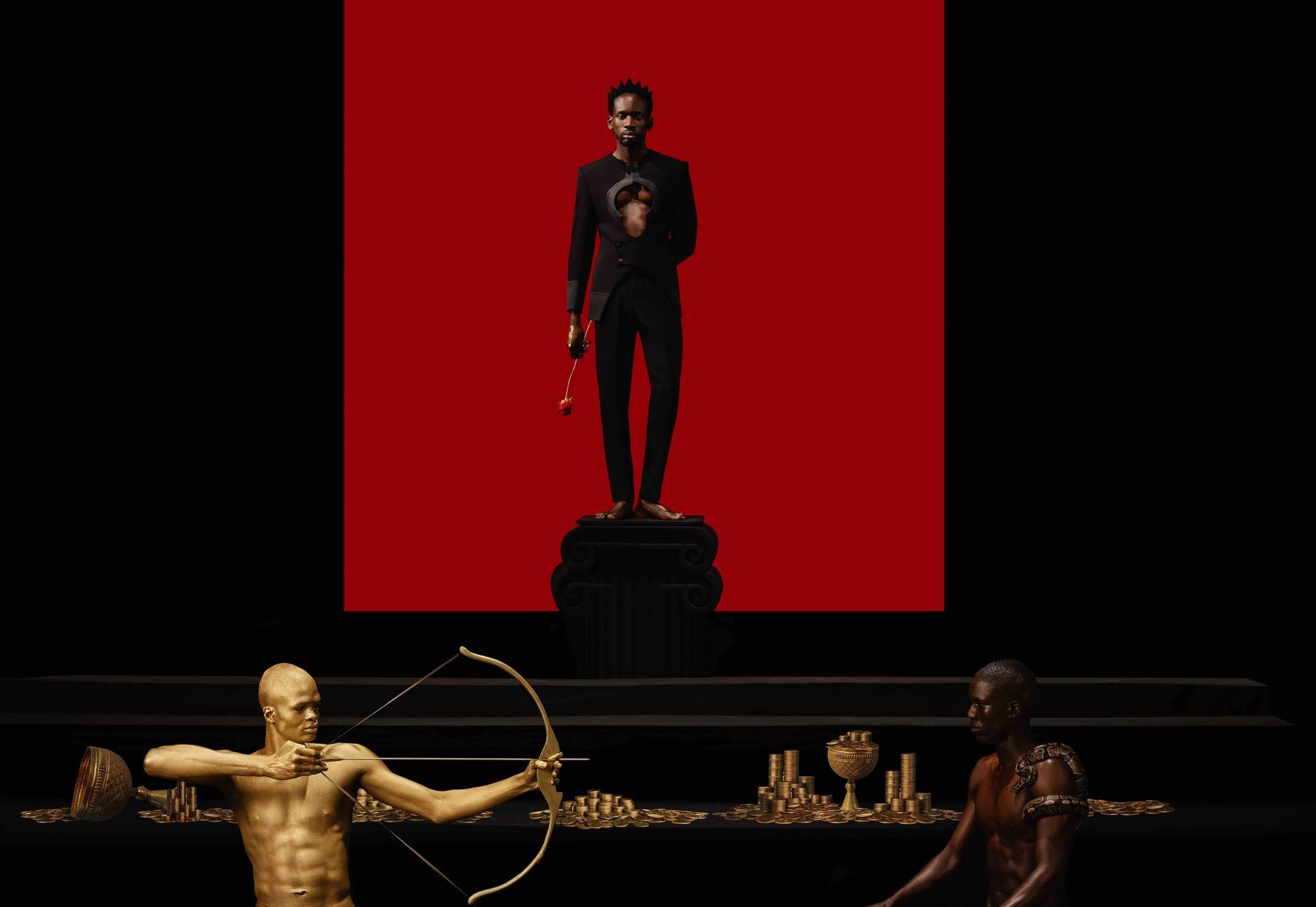

‘Re-Trace, Re-Memory, Re-Set, Re-Culture ’– VIVIERS ’SS24 Fashion Film: was conceptualised by Lezanne Viviers and brought to life by her long-time friend and photographer, Eva Losada, ‘Re-Trace, Re-Memory, Re-Set, Re-Culture’ is more than a fashion film; it’s an investigation into our collective history and shared Origin Stories. Exploring universal myths, legends, archaeological discoveries, astrology, visionary philosophy, and spiritual truths, the film is a patchwork of human experiences. From the Crystal Skulls to the Phoenix, from Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’ to Baba Credo Mutwa’s thoughts on ancient Gold astronauts, VIVIERS contemplates the potential for transformation and cultural redefinition. The stories in the film transcend borders, cultures, and religions, acting as bridges between our quest for truth and the interplay between the physical and metaphysical realms. The film embodies a vision of art and clothing as conduits for unity, connecting our shared history with our vision of a harmonious future.

Recent Comments