‘Gaolese Couture’: Crafting Haute Couture from the Heart of a Village

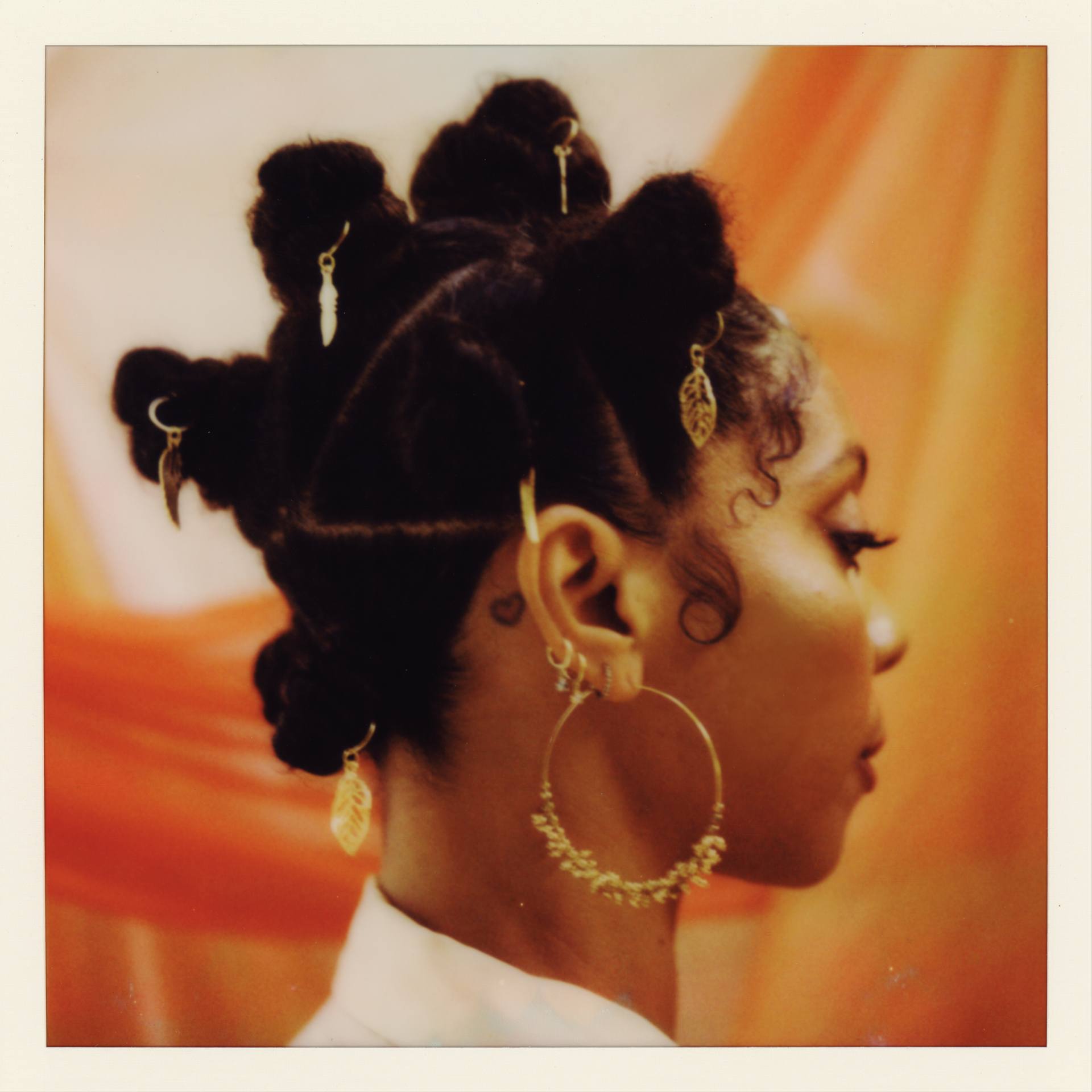

From the quiet rhythms of Ganyesa village in South Africa’s North West Province emerges a story of strength, heritage and high fashion. Gaolese Couture—founded by designer Kealeboga “Lebo” Maruping Appolus—weaves memory and modernity into garments that speak of legacy, resilience and love. This latest collection, shot and directed by her daughter Koketso “Coco” Maruping, redefines what couture can mean when crafted from the heart of a village.

Far from the glossy catwalks of Paris or Milan, Gaolese Couture celebrates the artistry of home. The brand is a living tribute to Gaolese, Lebo’s grandmother—a visionary seamstress who dressed many of Vryburg’s most prominent women. Through her hands, fashion became language, identity and quiet rebellion.

This collection continues that legacy. Shot against raw backdrops of earth, water, and concrete, the campaign is both a meditation on healing and a visual love letter to village life. After surviving a devastating accident that left her temporarily paralysed, Coco’s creative direction and photography mark a powerful return to artistry—a testimony to the unbreakable bond between creativity and recovery.

Mother and daughter worked side by side, merging heritage, memory and contemporary couture. Their collaboration carried a new gentleness, adapting to Coco’s physical recovery while deepening the emotional texture of the work. The result is a visual narrative that captures both the tenderness of healing and the boldness of reinvention.

All imagery courtesy of Koketso “Coco” Maruping

The garments, photographed amid textures of dust, stone, and water, embody the strength and softness of village life while asserting their place in the global language of haute couture.

The Garments

The Black Ensemble: a sculptural piece crafted from a special leather-like material, paired with a lace and sequin skirt. Its stark contrasts symbolise survival, pain and the courage to confront mortality.

The Red Velvet Look: made from guava-hued velvet, this look speaks to flesh, warmth, and the renewal of life. Its rich softness contrasts with the raw setting, suggesting both recovery and emotional depth.

The deliberate interplay of leather-like synthetics, lace, sequins and velvet mirrors the contradictions of the human experience—fragility and strength, loss and abundance, pain and beauty.

Rejecting polished studio backdrops, the shoot embraces the textures of the village: bare walls, raw earth, and open skies. These choices root the garments in lived experience, rejecting the notion that luxury belongs only to cities. In doing so, Gaolese Couture redefines couture as something that can rise from the soil—real, authentic and deeply human.

All imagery courtesy of Koketso “Coco” Maruping

Named after her grandmother, Gaolese Couture bridges generations. Each stitch is both tribute and evolution, a continuation of a woman’s vision that began decades ago in Vryburg.

For Lebo, the work is a dialogue with ancestry. For Coco, creative directing this campaign was a reclamation—of her body, her artistry and her voice after trauma. Together, they have created garments that are a testimony to the fashion that heals.

Each garment is handmade and one-of-a-kind, crafted in the family studio. Limited pieces are available upon request. For garment inquiries or custom orders, email: [email protected]

Creative Credits

Models: Nkatlo ‘Nuna’ Manyanye and Katlego ‘Masa’ Thlopile

Creative Direction: Kealeboga ‘Lebo’ Maruping Appolus and Koketso ‘Coco’ Maruping

Photography & Makeup: Koketso ‘Coco’ Maruping

Assistant: Fikile Manyanye

Press release courtesy of Koketso “Coco” Maruping

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za

Recent Comments