Tailoring for the Homies with Space Spinach

The art of tailoring is a study in workmanship and patience – and in a contemporary setting, it can feel like a waning pathway. Fashion & design are hyper-focused on the ‘creative director’ – and while necessary and brilliant in its own function, there is much to be said for the gritty, hands-on development a designer achieves through intimate knowledge of garment construction. Dennis Collins, the designer behind Space Spinach, has found himself using the term ‘tailor’ recently – although, entirely by chance. What began as mending clothes for his friends – many of whom are local skaters in the city, prone to slashes and rips – slowly became a micro-apparel brand, with Dennis making custom pieces on the side, learning from Youtube and a CMT on an industrial machine. Encouraged by his partner, Lindsey Raymond, to apply for G-Star RAW’s Certified Tailor Program : Dennis wasn’t sure he qualified, yet the program felt otherwise; now a program affiliate, Dennis finds himself alongside fellow tailors Samkelo Boyde Xaba (JHB) and Sabelo Shabalala (DBN) – the trio working to mend and revive for G-Star’s customers. A new realm has opened for Dennis; one in which his passion for making clothes is showing itself to be laden with possibility, and so apt for someone who seeks to learn everyday; from drafting, to fitting – stitching and finishings, there are few things as powerful as being able to make clothing.

It’s really only with the advent of fast-fashion that tailoring has since diminished as an integral community-role and service; although no less important, the art of tailoring, mending and re-inventing is precisely Dennis’ practice. Did everyone see those ostrich leather cargo pants that he recently dropped? Outrageously good. We caught up with Dennis in a Q+A format, for more insight into the brand’s shift from basic apparel and into this new frontier as a space for tailoring and craftsmanship.

Being both a designer and tailor is really interesting – in an age when we have lost a lot of understanding in everyday life that garment construction is a very technical skill. Can you describe a bit how this came about for you, being a tailor and designer?

In this age, everything is instant; nobody wants to wait and everyone wants results – fast! So, when my mom had a sewing machine and I had the option of making clothes rather than having to wait for someone else to do it for me, I took the opportunity. My first pair of trousers had a drawstring and were meant to be pull-up-and-go, ‘easy wear’ pants. I started tailoring them to fit well, and they just naturally became formal pants… but just ones that you could still skate in. I realised that the pants could be functional and beautiful.

What are you doing with G Star Raw at the moment and how has it deepened your work as a designer?

I help G-Star Raw provide a service to their clients by repairing any wear-and-tear on their jeans. So, we work together to revive denim. Collaborating with G-Star Raw definitely has made me want the level of craftsmanship and quality they achieve. But I’ve also taken note of the areas of garments exposed to the most strain, so it’s natural to want to look for solutions and incorporate that into your own designs.

The term sustainability is overdone and oversaturated, but how do you approach design in a conscious way?

I try to be conscious about everything. So, by default I am sustainable, but it also just happens to be. The total mass of garments that can be produced by a single industrial manufacturer can’t compare to the amount coming out of my home studio.

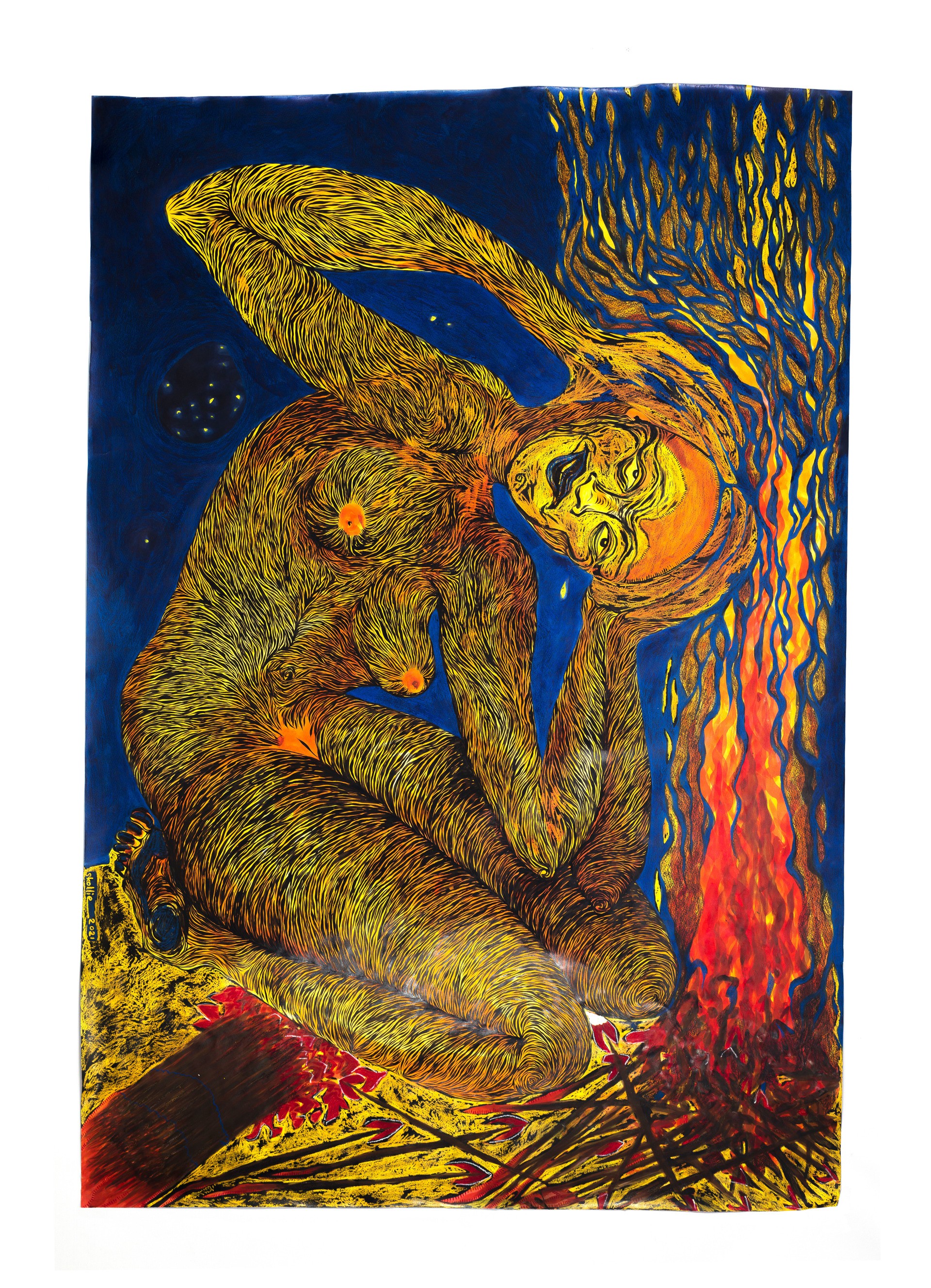

What does it mean to you to be a designer and what are your references and inspirations?

When you design, you share how limitless creativity can be and you communicate with people by making something they might respond to. You create a home for your ideas. My references are my daily life. Locally, I look back at old classics myself and so many others found in the emblematic Corner Store. Now, I look to the Broke Boys and everyone housed in Pot Plant Club (PPC). We all influence each other to excel and to produce something even better than the last time.

I’m also inspired by fabric stores, because so often I am guided by the materials I use: by how fun, different, and unique they are. And of course, Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren. I lean more towards looking at high fashion, those are the looks that excite me the most. Then, it all ties back to skating – that’s where Space Spinach comes from.

What is the vision forward for Space Spinach?

Growth! But also, consistency. We want to figure out how to tie skate culture, high fashion, streetwear, and art all together. And to always expand beyond what we know. We also want our own in-store studio and a space to hold and showcase our ideas. And eventually, to produce more numbers! But not to manufacture in a way that is harmful to the brand’s exclusivity.

Where does the name ‘Space Spinach’ come from?

It’s a playful euphemism that just stuck! If you know, you know! And if you don’t, now it’s just Space Spinach the brand and what it has become.

///

Kwezi wears a custom-fitted Golden Swamp Cargo Pants and SS Bucket Hat

Lindsey wears a Metallic Heavy Petal wrap-around dress accompanied by Clarkes and his custom Leather Patchwork Doggy-Fit

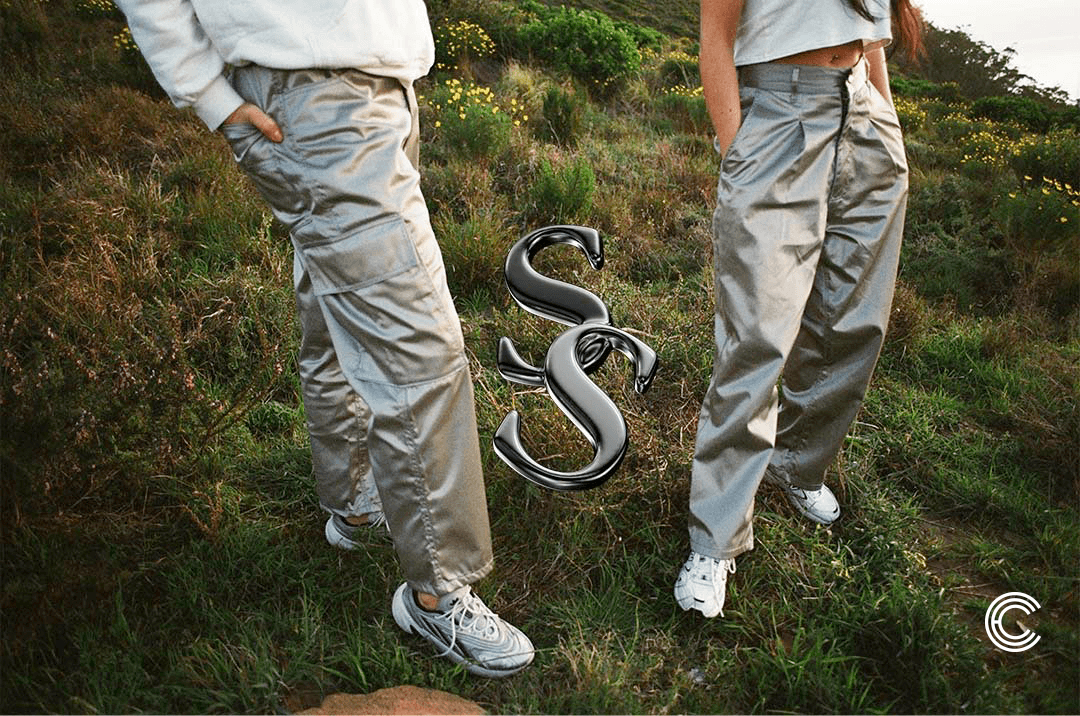

Lindsey wears the latest Cropped Hoody – the first of our in-house hoodies produced from our home studio, along with our Chrome Cargo Pants

Lea wears the Chrome Single-pleat Slacks and Forest Green SS Cap

Lea wears the Chrome Single-pleat Slacks as well as the Lime Green SS Hoody

Lea wears the Chrome Cargo Pants as well as the Lime Green SS Hoody and Foldable JACKET-IN-A-BAG Raincoat

Recent Comments