Laura Windvogel-Molifi AKA Lady Skollie is not a conversation or interview that one should research for – unbound by anything that may have been written about her previously in her decade long career – she has been through immense shifts in the last three years. So, we scrap everything you thought you knew; because while Laura’s core tenets remain artistically in her style, Laura shapes a new form in both herself and her work everyday. Rare is the moment to speak to an artist whose personality and work are so intertwined; far from the fine artist trope of having one’s work front-facing and their personhood subdued or discreet, Lady Skollie IS her art, and her paintings accompany this expression as a peek into her illuminated, illustrious inner-world.

“It seems like a cliché to say that I wanted to be an artist as a child, but it’s true. When I was very young and wrote with my left hand, I realised I could draw – so kids used to line up in class and ask me to draw them legs. Like many creative pursuits for a lot of people, art chose me – and I’ve been in the art world since I was about 8 years old. From that age, my mother sent me to Frank Joubert Art & Design Centre – now it’s called Peter Clarke Art Centre – until I was about 18. The famous and former principal Jill Joubert is a genius, and she really changed my life – I owe her a lot in terms of guidance.” Laura explains where her art education began, noting the quiet school in Claremont that has been a guardian of nurturing young, creative talent for decades. Now named after visual artist Peter Clarke, the centre pays homage to the legendary visual artist who created through six decades of both apartheid and democracy. After leaving Michaelis School of Fine Art after two years, Laura took a four year hiatus – “I wanted to see what else I could do. I tried fashion, and worked in shops – suddenly I was good at making sales, and speaking to people. I developed skills that I think have contributed to being able to make art full-time and as a fully fledged career. Working at AVA Gallery, I learnt a lot about art administration – and even though that’s only a few years ago, it’s in my living memory that art wasn’t a thing people did full-time, really. It was a side passion. I always lived in houses with people in advertising and marketing, so that could have been a thing I did – I loved strategy and copywriting – but I think morally, I was too evil or subversive for that world. I learnt a lot from those girls, though; especially about how to represent myself. In 2014, I quit my job and pursued art full-time – and I haven’t worked since in anything else.”

What shifted in a few short years that has seen the attention shift to art, as well as the encouragement for many to pursue it in South Africa? Speaking to this shift, Laura says “I think it’s because people realised they could shift their trauma in a way of making it this tangible thing. The resurgence of activism and discourse on oppression, presently and historically, but also just realising that one can resolve and vocalise their trauma through art. People were doing this before, for sure, but I think black and people of colour have started to feel far more comfortable in the art industry, whereas culturally we have been excluded from it; we have realised this space is for us. I also think the consumer started being more informed – and I also think things like FNB Art Fair, which are all new concepts, drive widespread interest. I think there has been a widespread involvement from all sides in nurturing art as viable and critical work to do in the world, and especially in our country.”

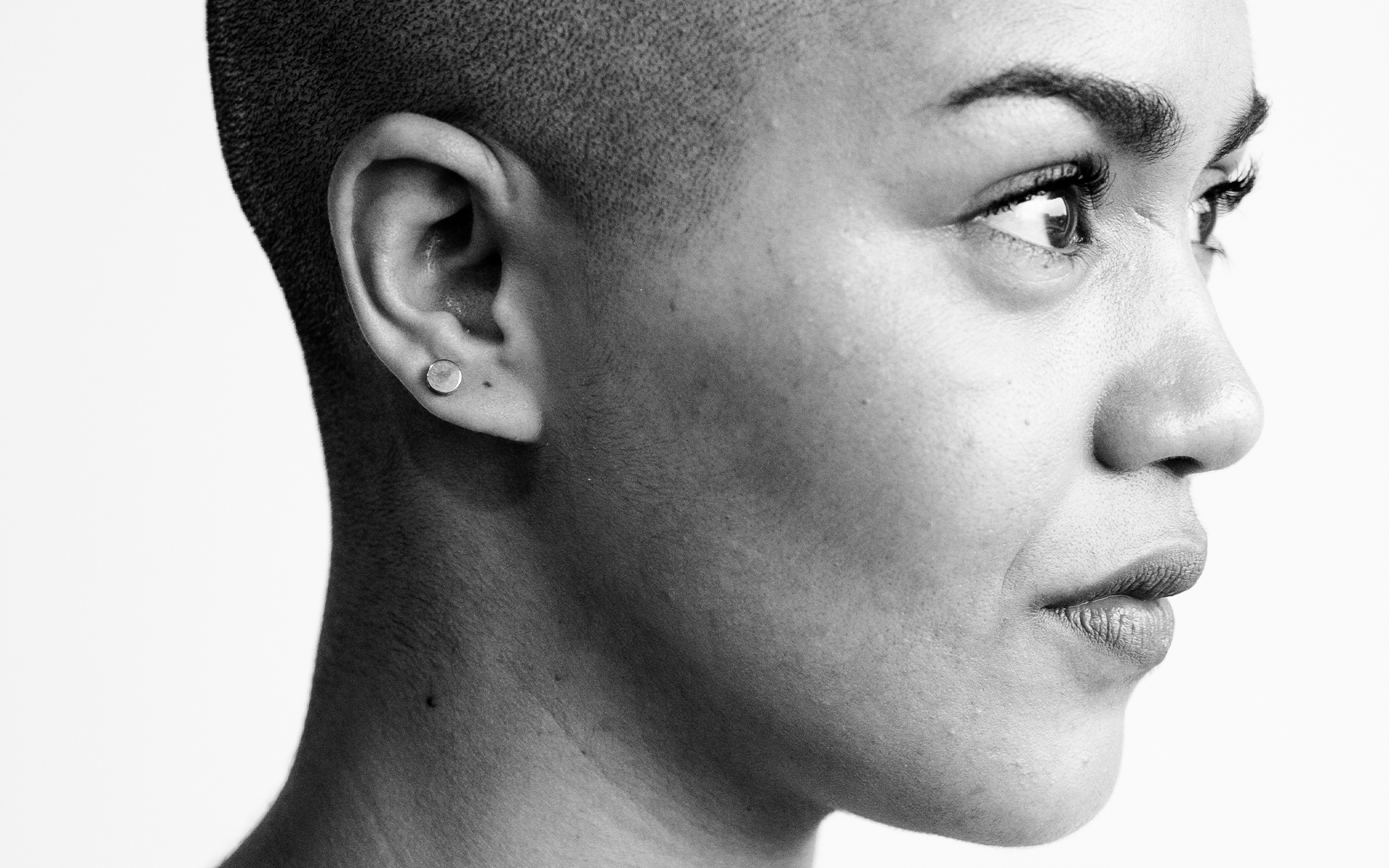

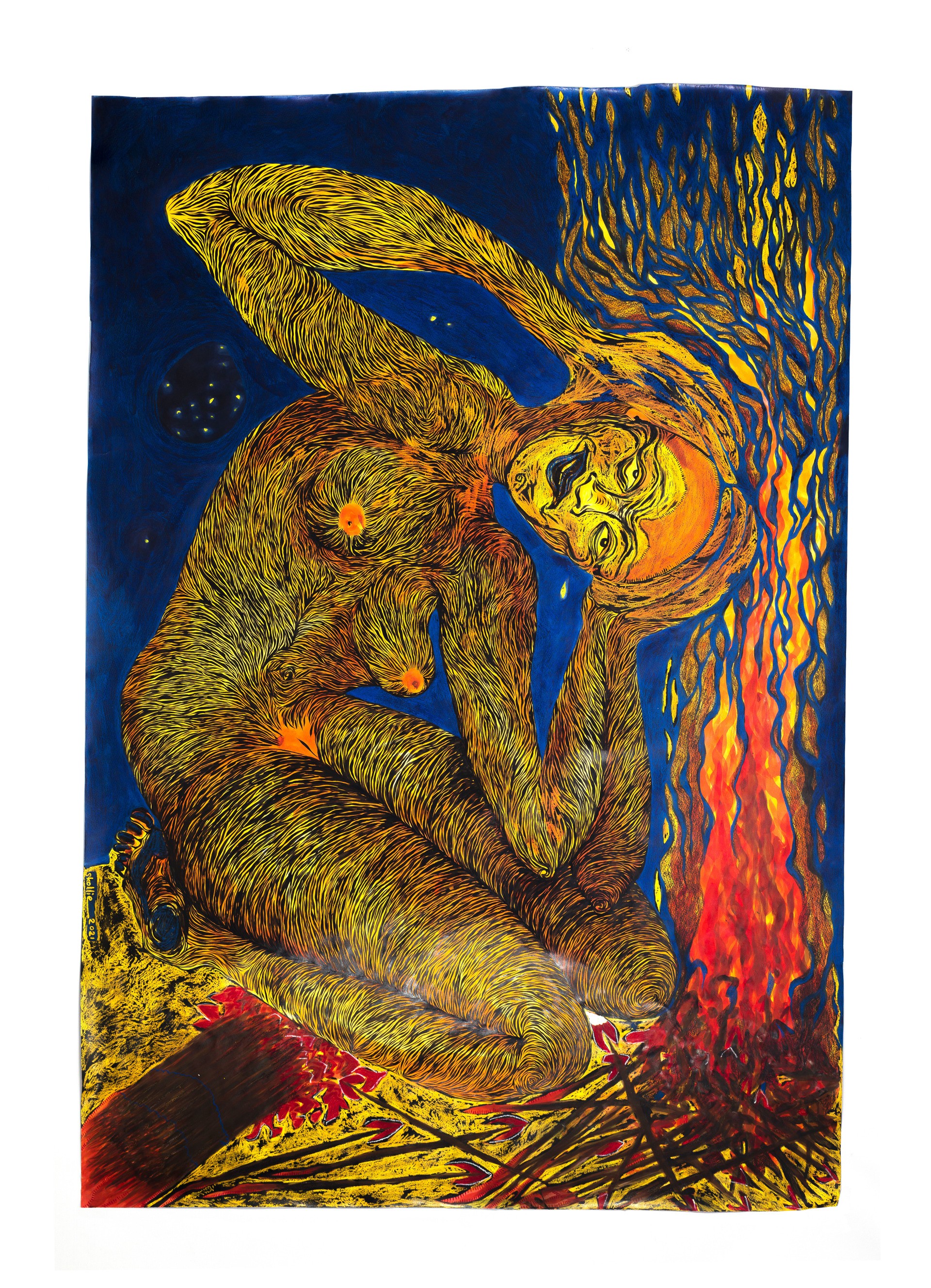

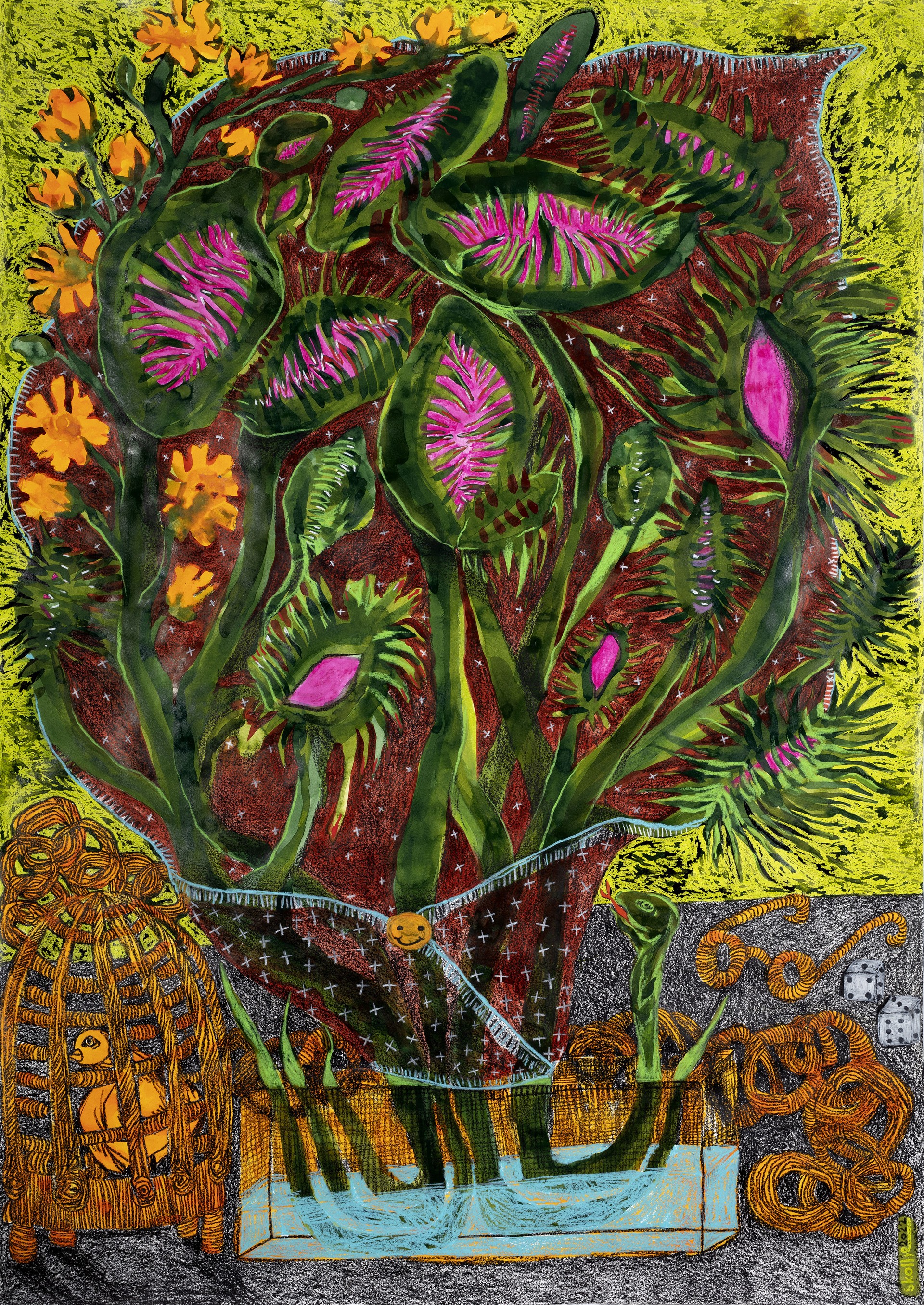

Laura explains her process, which often stems from writing, “I write a lot, and it’s usually the start of a work – writing, or something I dream. One of my favourite art movements is the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood – yeah, I love a bunch of old, white men that wanted to just have sex with the same woman! It was also the movement that brought us pink and purple in a profound way. I love the bible, great piece of fictional work – and all of my work has a messianic element, I think.” Laura’s notable use of archetypal figures is a fixture throughout her work, “The figure is me. It looks like me, it’s bald – how can artists really see but through themselves? I do see my work as big, pop art cave drawings. Since I was a child, my parents would take us to see the cave drawings in the country. I think there’s a comparison I draw to the culture of coloured people, Bushmen or San, or whatever you want to call it – and I see it as a stunted culture that couldn’t really bloom or fully manifest. To me, my work is like what would have happened if cave drawings became bigger, and bigger or crossed over to modern mediums. What if cave painting became pop culture?”

A strong association Laura has had with her work is feminism and activism – having been out spoken during waves of social change in South Africa, “I think that association has been with me because at the beginning of my career, I focused a lot on sexuality in my paintings – and then it came to looking at sex not being strictly about pleasure, particularly in the context of South Africa; sex is also violence, and so just by virtue of working with those themes, I was labelled an activist. My sister, Kim Windvogel, is an activist – I leave that to her. It’s been interesting because an artist commenting on social issues is not activism in the way my sister or many others have dedicated their lives and careers to that path – so I’m cautious about having that title put on me.” As an artist, Laura is dedicated to making fantastical work; to etch the fantasies and inner-world of her being, out for others to see. If her work can have a provoking impact, then that’s wonderful – but the immense pressure for black and coloured artists in the country to politicise their work entirely is in itself, a form of oppression of creative expression and freedom. In speaking to whether this is the responsibility – and in the age of the internet, especially – Laura says, “It’s become this trope, where if you’re not talking about your identity, then what are you really talking about? Of course we should be talking about it, and there is no cut off time to talk about it – as we were not allowed to – but often then there is more to us than trauma, and that needs to be liberated too.”

Laura found herself, a few years ago, putting on shows heavily focused on violence – and amassing the anger and energy, as if she was becoming the channel for it, ending up ill after those shows. Energetically hungover – with recuperation becoming longer and harder for her, Laura started to shift her practice, “Three years ago, I realised I couldn’t maintain it. In South Africa, it’s everyday – that anger and need for vengeance would rule my life – so I made a conscious effort to redirect my focus. I also had to stop fighting with people online, which became a never-ending distraction. People would start sending me links, asking why I hadn’t commented on something – almost demanding my voice – and that was a big wake-up that the expectations of me as a public figure were not so much about my art anymore. Since then, it’s been a return to what I need to feel safe, and to make work that speaks to whatever I want it – not what I am being told to comment on.”After Laura’s secret marriage in 2019, the last two years have been securing her vision ahead for artistic cosmology – creating her paintings as a continuation of a world that could be stitched together, and tell a story – this almost accidental nature of her style exemplifies Lady Skollie as an artist whose essence is inextricable from all that she does. We remain ever in awe.